Pragmatics

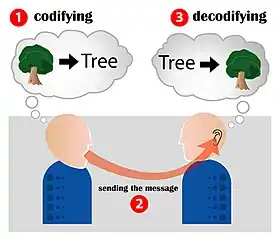

Pragmatics is a subfield of linguistics and semiotics that studies how context contributes to meaning. Pragmatics encompasses speech act theory, conversational implicature, talk in interaction and other approaches to language behavior in philosophy, sociology, linguistics and anthropology.[1] Unlike semantics, which examines meaning that is conventional or "coded" in a given language, pragmatics studies how the transmission of meaning depends not only on structural and linguistic knowledge (grammar, lexicon, etc.) of the speaker and listener but also on the context of the utterance,[2] any pre-existing knowledge about those involved, the inferred intent of the speaker, and other factors.[3] In that respect, pragmatics explains how language users are able to overcome apparent ambiguity since meaning relies on the manner, place, time, etc. of an utterance.[1][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

Pragmatic rules are used quite frequently by speakers but are rarely noticed unless the unspoken rules of pragmatics are broken. [5]

The ability to understand another speaker's intended meaning is called pragmatic competence.[6][7][8]

Etymology

The word pragmatics derives via Latin pragmaticus from the Greek πραγματικός (pragmatikos), meaning amongst others "fit for action",[9] which comes from πρᾶγμα (pragma) "deed, act" (in modern Greek πράγμα/pragma "an object, a thing that can be perceived by the senses"),[10] in turn from the verb πράσσω (prassō, Attic Greek πράττω - prattō) "to do, to act, to pass over, to practise, to achieve."[11]

Origins of the field

Pragmatics was a reaction to structuralist linguistics as outlined by Ferdinand de Saussure. In many cases, it expanded upon his idea that language has an analyzable structure, composed of parts that can be defined in relation to others. Pragmatics first engaged only in synchronic study, as opposed to examining the historical development of language. However, it rejected the notion that all meaning comes from signs existing purely in the abstract space of langue. Meanwhile, historical pragmatics has also come into being. The field did not gain linguists' attention until the 1970s, when two different schools emerged: the Anglo-American pragmatic thought and the European continental pragmatic thought (also called the perspective view).[12]

Areas of interest

- The study of the speaker's meaning focusing not on the phonetic or grammatical form of an utterance but on what the speaker's intentions and beliefs are.

- The study of the meaning in context and the influence that a given context can have on the message. It requires knowledge of the speaker's identities, and the place and time of the utterance.

- The study of implicatures: the things that are communicated even though they are not explicitly expressed.[13]

- The study of relative distance, both social and physical, between speakers in order to understand what determines the choice of what is said and what is not said.[14]

- The study of what is not meant, as opposed to the intended meaning: what is unsaid and unintended, or unintentional. [15]

- Information structure, the study of how utterances are marked in order to efficiently manage the common ground of referred entities between speaker and hearer.[16]

- Formal Pragmatics, the study of those aspects of meaning and use for which context of use is an important factor by using the methods and goals of formal semantics.

Ambiguity

The sentence "You have a green light" is ambiguous. Without knowing the context, the identity of the speaker or the speaker's intent, it is difficult to infer the meaning with certainty. For example, it could mean:

- the space that belongs to you has green ambient lighting;

- you are driving through a green traffic signal;

- you no longer have to wait to continue driving;

- you are permitted to proceed in a non-driving context;

- your body is cast in a greenish glow; or

- you possess a light bulb that is tinted green.

Another example of an ambiguous sentence is, “I went to the bank.” This is an example of lexical ambiguity, as the word bank can either be in reference to a place where money is kept, or the edge of a river. To understand what the speaker is truly saying, it is a matter of context, which is why it is pragmatically ambiguous as well. [17]

Similarly, the sentence "Sherlock saw the man with binoculars" could mean that Sherlock observed the man by using binoculars, or it could mean that Sherlock observed a man who was holding binoculars (syntactic ambiguity).[18] The meaning of the sentence depends on an understanding of the context and the speaker's intent. As defined in linguistics, a sentence is an abstract entity: a string of words divorced from non-linguistic context, as opposed to an utterance, which is a concrete example of a speech act in a specific context. The more closely conscious subjects stick to common words, idioms, phrasings, and topics, the more easily others can surmise their meaning; the further they stray from common expressions and topics, the wider the variations in interpretations. That suggests that sentences do not have intrinsic meaning, that there is no meaning associated with a sentence or word, and that either can represent an idea only symbolically. The cat sat on the mat is a sentence in English. If someone were to say to someone else, "The cat sat on the mat," the act is itself an utterance. That implies that a sentence, term, expression or word cannot symbolically represent a single true meaning; such meaning is underspecified (which cat sat on which mat?) and potentially ambiguous. By contrast, the meaning of an utterance can be inferred through knowledge of both its linguistic and non-linguistic contexts (which may or may not be sufficient to resolve ambiguity). In mathematics, with Berry's paradox, there arises a similar systematic ambiguity with the word "definable".

Referential uses of language

The referential uses of language are how signs are used to refer to certain items. A sign is the link or relationship between a signified and the signifier as defined by de Saussure and Huguenin. The signified is some entity or concept in the world. The signifier represents the signified. An example would be:

- Signified: the concept cat

- Signifier: the word "cat"

The relationship between the two gives the sign meaning. The relationship can be explained further by considering what we mean by "meaning." In pragmatics, there are two different types of meaning to consider: semantic-referential meaning and indexical meaning. [19] Semantic-referential meaning refers to the aspect of meaning, which describes events in the world that are independent of the circumstance they are uttered in. An example would be propositions such as:

- "Santa Claus eats cookies."

In this case, the proposition is describing that Santa Claus eats cookies. The meaning of the proposition does not rely on whether or not Santa Claus is eating cookies at the time of its utterance. Santa Claus could be eating cookies at any time and the meaning of the proposition would remain the same. The meaning is simply describing something that is the case in the world. In contrast, the proposition, "Santa Claus is eating a cookie right now," describes events that are happening at the time the proposition is uttered.

Semantic-referential meaning is also present in meta-semantical statements such as:

- Tiger: carnivorous, a mammal

If someone were to say that a tiger is a carnivorous animal in one context and a mammal in another, the definition of tiger would still be the same. The meaning of the sign tiger is describing some animal in the world, which does not change in either circumstance.

Indexical meaning, on the other hand, is dependent on the context of the utterance and has rules of use. By rules of use, it is meant that indexicals can tell you when they are used, but not what they actually mean.

- Example: "I"

Whom "I" refers to depends on the context and the person uttering it.

As mentioned, these meanings are brought about through the relationship between the signified and the signifier. One way to define the relationship is by placing signs in two categories: referential indexical signs, also called "shifters," and pure indexical signs.

Referential indexical signs are signs where the meaning shifts depending on the context hence the nickname "shifters." 'I' would be considered a referential indexical sign. The referential aspect of its meaning would be '1st person singular' while the indexical aspect would be the person who is speaking (refer above for definitions of semantic-referential and indexical meaning). Another example would be:

- "This"

- Referential: singular count

- Indexical: Close by

A pure indexical sign does not contribute to the meaning of the propositions at all. It is an example of a "non-referential use of language."

A second way to define the signified and signifier relationship is C.S. Peirce's Peircean Trichotomy. The components of the trichotomy are the following:

- 1. Icon: the signified resembles the signifier (signified: a dog's barking noise, signifier: bow-wow)[20]

- 2. Index: the signified and signifier are linked by proximity or the signifier has meaning only because it is pointing to the signified[20]

- 3. Symbol: the signified and signifier are arbitrarily linked (signified: a cat, signifier: the word cat)[20]

These relationships allow us to use signs to convey what we want to say. If two people were in a room and one of them wanted to refer to a characteristic of a chair in the room he would say "this chair has four legs" instead of "a chair has four legs." The former relies on context (indexical and referential meaning) by referring to a chair specifically in the room at that moment while the latter is independent of the context (semantico-referential meaning), meaning the concept chair.[20]

Referential Expressions and Discourse

Referential uses of language are entirely collaborative within the context of discourse. Individuals engaging in discourse utilize pragmatics.[21] In addition, individuals within the scope of discourse cannot help but avoid intuitive use of certain utterances or word choices in an effort to create communicative success. [21] The study of referential language is heavily focused upon definite descriptions and referrant accessibility. Theories have been presented for why direct referent descriptions occur in discourse.[22] (In layman's terms: why reiteration of certain names, places, or individuals involved or as a topic of the conversation at hand are repeated more than one would think necessary.) Four factors are widely accepted for the use of referent language including (i) competition with a possible referent, (ii) salience of the referent in the context of discussion (iii) an effort for unity of the parties involved, and finally, (iv) a blatant presence of distance from the last referent. [21]

Referential expressions are a form of anaphora. [22] They are also a means of connecting past and present thoughts together to create context for information at hand. Analyzing the context of a sentence and determining whether or not the use of referent expression is necessary is highly reliant upon the author/speaker's digression- and is correlated strongly with the use of pragmatic competency. [22][21]

Nonreferential uses of language

Silverstein's "Pure" Indexes

Michael Silverstein has argued that "nonreferential" or "pure" indices do not contribute to an utterance's referential meaning but instead "signal some particular value of one or more contextual variables."[23] Although nonreferential indexes are devoid of semantico-referential meaning, they do encode "pragmatic" meaning.

The sorts of contexts that such indexes can mark are varied. Examples include:

- Sex indexes are affixes or inflections that index the sex of the speaker, e.g. the verb forms of female Koasati speakers take the suffix "-s".

- Deference indexes are words that signal social differences (usually related to status or age) between the speaker and the addressee. The most common example of a deference index is the V form in a language with a T-V distinction, the widespread phenomenon in which there are multiple second-person pronouns that correspond to the addressee's relative status or familiarity to the speaker. Honorifics are another common form of deference index and demonstrate the speaker's respect or esteem for the addressee via special forms of address and/or self-humbling first-person pronouns.

- An Affinal taboo index is an example of avoidance speech that produces and reinforces sociological distance, as seen in the Aboriginal Dyirbal language of Australia. In that language and some others, there is a social taboo against the use of the everyday lexicon in the presence of certain relatives (mother-in-law, child-in-law, paternal aunt's child, and maternal uncle's child). If any of those relatives are present, a Dyirbal speaker has to switch to a completely separate lexicon reserved for that purpose.

In all of these cases, the semantico-referential meaning of the utterances is unchanged from that of the other possible (but often impermissible) forms, but the pragmatic meaning is vastly different.

The performative

J.L. Austin introduced the concept of the performative, contrasted in his writing with "constative" (i.e. descriptive) utterances. According to Austin's original formulation, a performative is a type of utterance characterized by two distinctive features:

- It is not truth-evaluable (i.e. it is neither true nor false)

- Its uttering performs an action rather than simply describing one

Examples:

- "I hereby pronounce you man and wife."

- "I accept your apology."

- "This meeting is now adjourned."

To be performative, an utterance must conform to various conditions involving what Austin calls felicity. These deal with things like appropriate context and the speaker's authority. For instance, when a couple has been arguing and the husband says to his wife that he accepts her apology even though she has offered nothing approaching an apology, his assertion is infelicitous: because she has made neither expression of regret nor request for forgiveness, there exists none to accept, and thus no act of accepting can possibly happen.

Jakobson's six functions of language

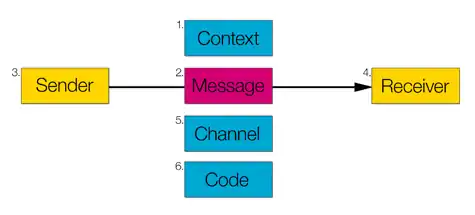

Roman Jakobson, expanding on the work of Karl Bühler, described six "constitutive factors" of a speech event, each of which represents the privileging of a corresponding function, and only one of which is the referential (which corresponds to the context of the speech event). The six constitutive factors and their corresponding functions are diagrammed below.

The six constitutive factors of a speech event

- Context

- Message

Addresser---------------------Addressee

- Contact

- Code

The six functions of language

- Referential

- Poetic

Emotive-----------------------Conative

- Phatic

- Metalingual

- The Referential Function corresponds to the factor of Context and describes a situation, object or mental state. The descriptive statements of the referential function can consist of both definite descriptions and deictic words, e.g. "The autumn leaves have all fallen now."

- The Expressive (alternatively called "emotive" or "affective") Function relates to the Addresser and is best exemplified by interjections and other sound changes that do not alter the denotative meaning of an utterance but do add information about the Addresser's (speaker's) internal state, e.g. "Wow, what a view!"

- The Conative Function engages the Addressee directly and is best illustrated by vocatives and imperatives, e.g. "Tom! Come inside and eat!"

- The Poetic Function focuses on "the message for its own sake"[25] and is the operative function in poetry as well as slogans.

- The Phatic Function is language for the sake of interaction and is therefore associated with the Contact factor. The Phatic Function can be observed in greetings and casual discussions of the weather, particularly with strangers.

- The Metalingual (alternatively called "metalinguistic" or "reflexive") Function is the use of language (what Jakobson calls "Code") to discuss or describe itself.

Related fields

There is considerable overlap between pragmatics and sociolinguistics, since both share an interest in linguistic meaning as determined by usage in a speech community. However, sociolinguists tend to be more interested in variations in language within such communities.

Pragmatics helps anthropologists relate elements of language to broader social phenomena; it thus pervades the field of linguistic anthropology. Because pragmatics describes generally the forces in play for a given utterance, it includes the study of power, gender, race, identity, and their interactions with individual speech acts. For example, the study of code switching directly relates to pragmatics, since a switch in code effects a shift in pragmatic force.[25]

According to Charles W. Morris, pragmatics tries to understand the relationship between signs and their users, while semantics tends to focus on the actual objects or ideas to which a word refers, and syntax (or "syntactics") examines relationships among signs or symbols. Semantics is the literal meaning of an idea whereas pragmatics is the implied meaning of the given idea.

Speech Act Theory, pioneered by J.L. Austin and further developed by John Searle, centers around the idea of the performative, a type of utterance that performs the very action it describes. Speech Act Theory's examination of Illocutionary Acts has many of the same goals as pragmatics, as outlined above.

Computational Pragmatics, as defined by Victoria Fromkin, concerns how humans can communicate their intentions to computers with as little ambiguity as possible.[26] That process, integral to the science of natural language processing (seen as a sub-discipline of artificial intelligence), involves providing a computer system with some database of knowledge related to a topic and a series of algorithms, which control how the system responds to incoming data, using contextual knowledge to more accurately approximate natural human language and information processing abilities. Reference resolution, how a computer determines when two objects are different or not, is one of the most important tasks of computational pragmatics.

Formalization

There has been a great amount of discussion on the boundary between semantics and pragmatics [27] and there are many different formalizations of aspects of pragmatics linked to context dependence. Particularly interesting cases are the discussions on the semantics of indexicals and the problem of referential descriptions, a topic developed after the theories of Keith Donnellan.[28] A proper logical theory of formal pragmatics has been developed by Carlo Dalla Pozza, according to which it is possible to connect classical semantics (treating propositional contents as true or false) and intuitionistic semantics (dealing with illocutionary forces). The presentation of a formal treatment of pragmatics appears to be a development of the Fregean idea of assertion sign as formal sign of the act of assertion.

In literary theory

Pragmatics (more specifically, Speech Act Theory's notion of the performative) underpins Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity. In Gender Trouble, she claims that gender and sex are not natural categories, but socially constructed roles produced by "reiterative acting."

In Excitable Speech she extends her theory of performativity to hate speech and censorship, arguing that censorship necessarily strengthens any discourse it tries to suppress and therefore, since the state has sole power to define hate speech legally, it is the state that makes hate speech performative.

Jacques Derrida remarked that some work done under Pragmatics aligned well with the program he outlined in his book Of Grammatology.

Émile Benveniste argued that the pronouns "I" and "you" are fundamentally distinct from other pronouns because of their role in creating the subject.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari discuss linguistic pragmatics in the fourth chapter of A Thousand Plateaus ("November 20, 1923--Postulates of Linguistics"). They draw three conclusions from Austin: (1) A performative utterance does not communicate information about an act second-hand, but it is the act; (2) Every aspect of language ("semantics, syntactics, or even phonematics") functionally interacts with pragmatics; (3) There is no distinction between language and speech. This last conclusion attempts to refute Saussure's division between langue and parole and Chomsky's distinction between deep structure and surface structure simultaneously.[29]

Significant works and concepts

- J. L. Austin's How To Do Things With Words

- Paul Grice's cooperative principle and conversational maxims

- Brown and Levinson's politeness theory

- Geoffrey Leech's politeness maxims

- Levinson's presumptive meanings

- Jürgen Habermas's universal pragmatics

- Dan Sperber and Deirdre Wilson's relevance theory

- Dallin D. Oaks's Structural Ambiguity in English: An Applied Grammatical Inventory

- Vonk, Hustinx, and Simon's Referential Expression Journal

See also

- Anaphora – Use of an expression whose interpretation depends on context

- Co-construction

- Collapsing sequence

- Cooperative principle

- Deixis – Words requiring context to understand their meaning

- Implicature

- Indexicality – Phenomenon of a sign pointing to (or indexing) some object in the context in which it occurs

- Origo (pragmatics)

- Paul Grice

- Presupposition

- Semantics – Study of meaning in language

- Semiotics – The study of signs and sign processes

- Sign relation – Concept in semiotics

- Sitz im Leben

- Speech act – Utterance that serves a performative function

- Stylistics

- Universal pragmatics

Notes

- Mey, Jacob L. (1993) Pragmatics: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell (2nd ed. 2001).

- "Meaning (Semantics and Pragmatics) | Linguistic Society of America". www.linguisticsociety.org. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- Shaozhong, Liu. "What is pragmatics?". Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "What Is Pragmatics?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- Bardovi-Harlig, Mahan-Taylor, Kathleen, Rebecca (July 2003). "Introduction to Teaching Pragmatics" (PDF). English Teaching Forum: 39.

- Daejin Kim et al. (2002) "The Role of an Interactive Book Reading Program in the Development of Second Language Pragmatic Competence", The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 86, No. 3 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 332-348

- Masahiro Takimoto (2008) "The Effects of Deductive and Inductive Instruction on the Development of Language Learners' Pragmatic Competence", The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 92, No. 3 (Fall, 2008), pp. 369-386

- Dale April Koike (1989) "Pragmatic Competence and Adult L2 Acquisition: Speech Acts in Interlanguage", The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 279-289

- πραγματικός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- πρᾶγμα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- πράσσω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Jucker, Andreas H (2012). "Pragmatics in the history of linguistic thought" (PDF). www.zora.uzh.ch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-23.

- "What is Pragmatics? - Definition & Examples - Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com". study.com. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- "Definition of PRAGMATICS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- Leigh, Karen (2018-03-03). "What are Pragmatic Language Skills?". Sensational Kids. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Information Structure - Linguistics - Oxford Bibliographies - obo". www.oxfordbibliographies.com. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- "What is pragmatics? – All About Linguistics". Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- "24.903 / 24.933 Language and its Structure III: Semantics and Pragmatics". MIT.edu. MIT OpenCourseWare, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2004. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- Treanor, Fergal. "Pragmatics and Indexicality - A very short overview". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Icon, Index and Symbol: Types of Signs". www.cs.indiana.edu. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- Almor, Nair, Amit, Veena (2007). "The Form of Referential Expressions in Discourse" (PDF). Language and Linguistics Compass, University of South Carolina. 10: 99 – via Wiley Online Library.

- Vonk, Hustinx, Simons (1992). "The Use of Referential Expressions in Structuring Discourse". Taylor and Francis: 333.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Silverstein 1976

- Middleton, Richard (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music, p. 241. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- Duranti 1997

- Fromkin, Victoria (2014). Introduction to Language. Boston, Ma.: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 508. ISBN 978-1133310686.

- see for instance F.Domaneschi. C. Penco, What is Said and What is Not, CSLI Publication, Stanford

- see for instance S. Neale, Descriptions, 1990

- Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari (1987) [1980]. A Thousand Plateaus. University of Minnesota Press.

References

- Austin, J. L. (1962) How to Do Things With Words. Oxford University Press.

- Ariel, Mira (2008), Pragmatics and Grammar, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ariel, Mira (2010). Defining Pragmatics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73203-1.

- Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. (1978) Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge University Press.

- Carston, Robyn (2002) Thoughts and Utterances: The Pragmatics of Explicit Communication. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Clark, Herbert H. (1996) "Using Language". Cambridge University Press.

- Cole, Peter, ed.. (1978) Pragmatics. (Syntax and Semantics, 9). New York: Academic Press.

- Dijk, Teun A. van. (1977) Text and Context. Explorations in the Semantics and Pragmatics of Discourse. London: Longman.

- Grice, H. Paul. (1989) Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- Laurence R. Horn and Gregory Ward. (2005) The Handbook of Pragmatics. Blackwell.

- Leech, Geoffrey N. (1983) Principles of Pragmatics. London: Longman.

- Levinson, Stephen C. (1983) Pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

- Levinson, Stephen C. (2000). Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. MIT Press.

- Lin, G. H. C., & Perkins, L. (2005). Cross-cultural discourse of giving and accepting gifts. International Journal of Communication, 16,1-2, 103-12 (ERIC Collections in ED 503685 http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED503685.pdf)

- Moumni, Hassan (2005). Politeness in Parliamentary Discourse : A Comparative Pragmatic Study of British and Moroccan MPs’ Speech Acts at Question Time. Unpub. Ph.D. Thesis. Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco.

- Mey, Jacob L. (1993) Pragmatics: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell (2nd ed. 2001).

- Kepa Korta and John Perry. (2006) Pragmatics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Potts, Christopher. (2005) The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Robinson, Douglas. (2003). Performative Linguistics: Speaking and Translating as Doing Things With Words. London and New York: Routledge.

- Robinson, Douglas. (2006). Introducing Performative Pragmatics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sperber, Dan and Wilson, Deirdre. (2005) Pragmatics. In F. Jackson and M. Smith (eds.) Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy. OUP, Oxford, 468-501. (Also available here.)

- Thomas, Jenny (1995) Meaning in Interaction: An Introduction to Pragmatics. Longman.

- Verschueren, Jef. (1999) Understanding Pragmatics. London, New York: Arnold Publishers.

- Verschueren, Jef, Jan-Ola Östman, Jan Blommaert, eds. (1995) Handbook of Pragmatics. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Watzlawick, Paul, Janet Helmick Beavin and Don D. Jackson (1967) Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies, and Paradoxes. New York: Norton.

- Wierzbicka, Anna (1991) Cross-cultural Pragmatics. The Semantics of Human Interaction. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Yule, George (1996) Pragmatics (Oxford Introductions to Language Study). Oxford University Press.

- Silverstein, Michael. 1976. "Shifters, Linguistic Categories, and Cultural Description," in Meaning and Anthropology, Basso and Selby, eds. New York: Harper & Row

- Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006). "An Introduction to Sociolinguistics". Blackwell.

- Duranti, Alessandro. (1997). "Linguistic Anthropology". Cambridge University Press.

- Carbaugh, Donal. (1990). "Cultural Communication and Intercultural Contact." LEA.

External links

- Meaning and Context Sensitivity, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- International Pragmatics Association (IPrA)

- Journal of Pragmatics

- "What is Pragmatics?" (eprint) by Shaozhong Liu

- European Communicative Strategies (ECSTRA), a (wiki)project in comparative pragmatics directed by Joachim Grzega.