Qutb Shahi dynasty

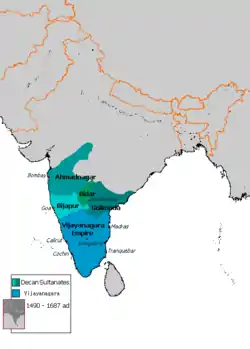

The Qutb Shahi dynasty ruled the Golconda Sultanate in south India from 1518 AD to 1687 AD. The Qutb Shahis were descendants of Qara Yusuf from Qara Qoyunlu, a Turkoman Muslim tribe. After the collapse of Bahmani Sultanate, the "Qutb Shahi" dynasty was established in 1518 AD by Quli Qutb Mulk who assumed the title of "Sultan". In 1636, Shah Jahan forced the Qutb Shahis to recognize Mughal suzerainty. The dynasty came to an end in 1687 during the reign of its seventh Sultan Abul Hasan Qutb Shah, when Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb seized Golconda fort and occupied the kingdom.[3][4][5] The kingdom extended from the parts of modern day states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.[6] The Golconda sultanate was constantly in conflict with the Adil Shahis and Nizam Shahis.[5]

Golconda Sultanate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1518–1687 | |||||||||

Flag of the Qutb Shahis | |||||||||

Extent of Golconda Sultanate | |||||||||

| Capital | Golconda (1519-1591) Hyderabad (1591-1687) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (official)[1] Telugu[2] Deccani Urdu | ||||||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Qutb Shah | |||||||||

• 1512–1543 | Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk | ||||||||

• 1543–1550 | Jamsheed Quli Qutb Shah | ||||||||

• 1550–1550 | Subhan Quli Qutb Shah | ||||||||

• 1550–1580 | Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah | ||||||||

• 1580-1612 | Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah | ||||||||

• 1612-1626 | Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah | ||||||||

• 1626–1672 | Abdullah Qutb Shah | ||||||||

• 1672-1686 | Abul Hasan Qutb Shah | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1518 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1687 | ||||||||

| Currency | Mohur | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

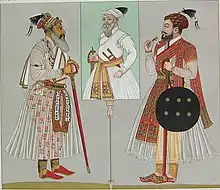

The Qutb Shahis were great patrons of persianate Shia culture,[4] eventually it also adopted the regional culture of the Deccan (Telugu culture, language and the newly developed Deccani dialect of Urdu). Although Telugu was not their mother tongue, the Golconda rulers spoke and wrote Telugu,[7] and patronized Telugu so exclusively that they were termed the "Telugu Sultans".[8] The Qutb Shahis were known for their secular rule.[9]

History

.jpg.webp)

The dynasty's founder, Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk was a descendants of Qara Yusuf (from Qara Qoyunlu, a Turkish Muslim tribe). He migrated to Delhi with his uncle, Allah-Quli, some of his relatives and friends in the beginning of the 16th century, from Hamadan Province—(now in Iran then it was ruled by his ancestral Turkish tribe).[10][11] Later he migrated south, to the Deccan and served the Bahmani sultan, Mahmood Shah Bahmani II.[12] He conquered Golconda, after the disintegration of the Bahmani Kingdom into the five Deccan sultanates.[12] Soon after, he declared independence from the Bahmani Sultanate, took the title Qutub Shah, and established the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda. He was later assassinated in 1543 by his son, Jamsheed, who assumed the sultanate.[12] Jamsheed died in 1550 from cancer.[13] Jamsheed's young son reigned for a year, at which time the nobility brought back and installed Ibrahim Quli as sultan.[13] During the reign of Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, relations between Hindus and Muslims were strengthened, even to the point of Hindus resuming their religious festivals like Diwali and Holi.[14] Some Hindus rose to prominence in the Qutb Shahi state, the most important example being the ministers Madanna and Akkanna.

Golconda, and with the construction of the Char Minar, later Hyderabad, served as capitals of the sultanate,[12] and both cities were embellished by the Qutb Shahi sultans. The dynasty ruled Golconda for 171 years, until the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb conquered the Deccan in 1687.[15]

Economy

During the early seventeenth century a strong cotton-weaving industry existed in the Deccan region. Large quantities of cotton cloth were produced for domestic and exports consumption. High quality plain and patterned cloth made of muslin and calico was produced. Plain cloth was available as white or brown colour, in bleached or dyed variety. Exports of this cloth was to Persia and European countries. Patterned cloth was made of prints which were made indigenously with indigo for blue, chay-root for red coloured prints and vegetable yellow. Patterned cloth exports were mainly to Java, Sumatra and other eastern countries.[16]

Culture

The Qutb Shahi rulers were great builders, whose structures included the Char Minar,[7] as well as patrons of learning. Quli Qutb Mulk's court became a haven for Persian culture and literature.[5] Sultan Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah (1580–1612) wrote poems in Dakhini Urdu, Persian and Telugu and left a huge poetry collection.[7] Subsequent poets and writers, however wrote in Urdu, while using vocabulary from Persian, Hindi and Telugu languages.[7] By 1535, the Qutb Shahis were using Telugu for their revenue and judicial areas within the sultanate.[17]

Initially, the Qutb Shahi rulers patronized Turkish culture, but eventually adopted the regional culture of the Deccan, symbolized by the Telugu language and the newly developed Deccani idiom and Urdu became prominent.[18] Although Telugu was not their mother tongue, the Golconda rulers spoke and wrote Telugu,[7] and patronized Telugu so exclusively they were termed the "Telugu Sultans".[8] In 1543, fearing for his life, Prince Ibrahim Quli fled to the Vijayanagar court, which lavishly patronized the Telugu language. Upon his enthronement as sultan in 1550, Ibrahim Quli was thoroughly acquainted with Telugu aesthetics.[8]

The Qutb Shahi rulers were much more liberal than their other Muslim counterparts. During the reign of Abdullah Qutb Shah in 1634 CE, the ancient Indian sex manual Koka Shastra was translated into Persian named Lazzat-un-Nisa (Flavors of the Woman).[19]

Architecture

The Qutb Shahi architecture was Indo-Islamic, a culmination of Indian and Persian architectural styles.[20] Their style was very similar to that of the other Deccan Sultanates.

Some examples of Qutb Shahi Indo-Islamic architecture are the Golconda Fort, tombs of the Qutb Shahis, Char Minar and the Char Kaman, Mecca Masjid, Khairtabad Mosque, Hayat Bakshi Mosque, Taramati Baradari and the Toli Mosque.[20][21]

Administration

The Qutb Shahi Kingdom was like the other Deccan kingdoms, a highly centralized state. The sultan enjoyed absolute executive judicial and military powers. When expediency demanded, the post of regent was created to carry on the administration on behalf of the king.

The Peshwa (Prime Minister) was the highest official of the sultanate. He was assisted by a number of ministers, including Mir Jumla (finance minister), Kotwal (police commissioner), and Khazanadar (treasurer).

In the Qutb Shahi kingdom, all the muslims were paid allowances from the treasury. The Persian origin muslims had the highest respect and were paid the highest, then the other Indian muslims. The Persian origin muslims became rich by lending money on high interest (usury) of 4-5% per mensem much to the despair of Hindus.[16]

The Sultanate had 66 forts, and each fort was administered by Nayak.[22] The Qutb Shahis hired many Hindu Nayaks belonging mainly to the Kamma, Velama, Kapu, and Raju communities.[23] These groups mainly were the regional aristocracy,[24] served as revenue officers[25] and military commanders,[23] but many of them fell into obscurity following the fall of the Qutb Shahis in 1687.

Tax collection was through auction farms, the highest bidder used to get the Governorship. While the Governors enjoyed luxurious life style, they had to bear the brunt of severe punishments for default, consequently they were harsh on the people. People were in distress as the complaints of the poor never reached the sultans.[16]

Religion

The Qutb Shahi dynasty has been considered a "composite" of Hindu-Muslim religio-social culture.[26] For instance, the Qutb Shahis began the sacred tradition of sending pearls to the Bhadrachalam Temple of Rama on Rama Navami.[27]

Rulers

The eight sultans in the dynasty were:

| Personal Name | Titular Name | Reign | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | Until | |||

| Quli Qutb Shah قلی قطب شاہ |

Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk | 1512 | 1543 |

|

| Jamsheed جمشید |

Jamsheed Quli Qutb Shah | 1543 | 1550 |

|

| Subhan سبحان |

Subhan Quli Qutb Shah | 1550 | 1550 |

|

| Ibrahim ابراہیم |

Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah Wali | 1550 | 1580 |

|

| Muhammad Ali محمد علی |

Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah | 1580 | 1612 | |

| Sultan Muhammad محمد سلطان |

Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah | 1612 | 1626 |

|

| Abdullah عبداللہ |

Abdullah Qutb Shah | 1626 | 1672 |

|

| Abul Hasan ابُل حسن |

Tana Shah | 1672 | 1686 |

|

Tombs

The tombs of the Qutb Shahi sultans lie about one kilometer north of Golkonda's outer wall. These structures are made of beautifully carved stonework, and surrounded by landscaped gardens. They are open to the public and receive many visitors.[21]

Qutb Shahi lineage

| Qara Yusuf Ruler of the Qara Qoyunlu 1410-1420 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qara Iskander Ruler of the Qara Qoyunlu First Reign 1420-1429 Second Reign 1431-1436 | Jahan Shah Ruler of the Qara Qoyunlu 1436-1467 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alvand Mirza | Mirza Yusuf Ruler of the Qara Qoyunlu 1468-1469 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pir Quli Beg | Khadija Khatun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uways Quli Beg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Quli Qutb Mulk Sultan of Golkonda 1512-1543 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah Wali Sultan of Golkonda 1550-1580 | 2. Jamsheed Quli Qutb Shah Sultan of Golkonda 1543-1550 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mirza Muhammad Amin | 5. Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah Sultan of Golkonda 1580-1611 | 3. Subhan Quli Qutb Shah Sultan of Golkonda 1550 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Muhammad Qutb Shah Sultan of Golkonda 1611-1626 | Hayat Balksh Begum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Abdullah Qutb Shah Sultan of Golkonda 1626-1672 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Abul Hasan Qutb Shah Sultan of Golkonda 1672-1687 | Badshah Bibi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Brian Spooner and William L. Hanaway, Literacy in the Persianate World: Writing and the Social Order, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 317.

- Alam, Muzaffar (1998). "The pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics". Modern Asian Studies. 32 (2): 317–349. doi:10.1017/s0026749x98002947.

Ibrahim Qutb Shah encouraged the growth of Telugu and his successor Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah patronized and himself wrote poetry in Telugu and in Dakhni. Abdullah Qutb Shah instituted a special office to prepare the royal edicts in Telugu (dabiri-ye faramin-i Hindavi). While administrative and revenue papers at local levels in the Qutb Shahi Sultanate were prepared largely in Telugu, the royal edicts were often bilingual.'06 The last Qutb Shahi Sultan, Abul Hasan Tana Shah, sometimes issued his orders only in Telugu, with a Persian summary given on the back of the farmans.

- Keelan Overton (2020). Iran and the Deccan: Persianate Art, Culture, and Talent in Circulation, 1400–1700. Indiana University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780253048943. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Farooqui Salma Ahmed (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 177–179. ISBN 9788131732021.

- C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 328.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- Satish Chandra, Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, Part II, (Har-Anand, 2009), 210.

- Richard M. Eaton, A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives, Vol. 1, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 142-143.

- Nigam, Mohan Lal; Bhatnagar, Anupama (1997). Romance of Hyderabad Culture. Deva Publications. p. 50.

- Minorsky, V. (1955). "The Qara-qoyunlu and the Qutb-shāhs (Turkmenica, 10)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Cambridge University Pres. 17 (1): 50–73. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00106342. JSTOR 609229. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Khan, Masud Husain (1996). Mohammad Quli Qutb Shah. Sahitya Akademi. p. 2. ISBN 9788126002337. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- George Michell, Mark Zebrowski, Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 17.

- Masʻūd Ḥusain K̲h̲ān̲, Mohammad Quli Qutb Shah, Volume 216, (Sahitya Akademi, 1996), 2.

- Annemarie Schimmel, Classical Urdu Literature from the Beginning to Iqbāl, (Otto Harrassowitz, 1975), 143.

- Satish Chandra, Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, Part II, (Har-Anand, 2009), 331.

- Moreland, W.H. (1931). Relation of Golconda in the Early Seventeenth Century. Halyukt Society. pp. 78, 89.

- A Social and Historical Introduction to the Deccan, 1323-1687, Richard M. Eaton, Sultans of the South: Arts of India's Deccan Courts, 1323-1687, ed. Navina Najat Haidar, Marika Sardar, (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2011), 8.

- "Opinion A Hyderabadi conundrum". 15 November 2018.

- Akbar, Syed (5 January 2019). "Lazzat-Un-Nisa: Hyderabad's own Kamasutra back in focus - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Salma Ahmed Farooqui, A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century, (Dorling Kindersley Pvt. Ltd, 2011), 181.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Qutb Shahi Monuments of Hyderabad Golconda Fort, Qutb Shahi Tombs, Charminar - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Narendra Luther (1991). Prince;Poet;Lover;Builder: Mohd. Quli Qutb Shah - The founder of Hyderabad. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. ISBN 9788123023151. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Chapter III: Economics, Political, Economic, and Social Background of Deccan 17th-18th Century, p.57 https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/25652/10/10_chapter%203.pdfhttps://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/25652/10/10_chapter%203.pdf

- Reddy, Pedarapu Chenna (1 January 2006). Readings In Society And Religion Of Medieval South India. Research India Press. p. 163. ISBN 9788189131043.

- Proceedings of Seminar on Industries and Crafts in Andhra Desa, 17th and 18th Centuries, A.D. Department of History, Osmania University. 1996. p. 57.

- Islam in South Asia: Practicing tradition today, Karen G. Ruffle, South Asian Religions: Tradition and Today, ed. Karen Pechilis, Selva J. Raj, (Routledge, 2013), 210.

- Sarma, Mukkamala Radhakrishna; Committee, Osmania University Dept of Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology Felicitation; History, Osmania University Dept of (2004). Glimpses of our past--historical researches: festschrift in honour of Prof. Mukkamala Radhakrishna Sarma, former emeritus fellow. Felicitation Committee, Dept. of Ancient Indian History, Culture, and Archaeology & Dept. of History, Osmania University. p. 326.

Further reading

- Chopra, R. M., The Rise, Growth And Decline of Indo-Persian Literature, 2012, Iran Culture House, New Delhi.

- Jawed Vashisht, Ghizal-e Raana (A selection of Quli Qutab Shah's ghazals)

- Jawed Vashisht, Roop Ras (Romantic poems of Quli Qutab Shah)

- Jawed Vashisht, Mohammed Quli aur Nabi ka Sadka

- Jawed Vashisht, Dakhni Darpan

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qutb Shahi dynasty. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Qutb Shahi dynasty |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hyderabad. |