Turkoman (ethnonym)

Turkoman (Middle Turkic: تُركْمانْ, Ottoman Turkish: تركمن, romanized: Türkmen and Türkmân, Azerbaijani: Türkman and Türkmən, Turkish: Türkmen, Turkmen: Türkmen, Persian: sing. Turkamān, pl. Tarākimah,[1] also called Turcoman and Turkman) is a term that was widely used during the Middle Ages for the people of Oghuz Turkic origin.[2][3][4] According to medieval authors Al-Biruni and al-Marwazi, this term referred to the Oghuz who converted to Islam.[5] There is evidence non-Oghuz Turks such as Karluks may also have been called Turkomans and Turkmens.[6]

تركمنلر Türkmenler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central Asia, South Caucasus, Middle East | |

| Languages | |

| Oghuz Turkic (Azerbaijani · Turkmen · Turkish) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam (Sunni · Alevi · Bektashi · Twelver Shia) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Turkic people |

The term, which was originally an exonym, is thought to date from the high Middle Ages, along with the ancient and familiar name Turk (türk) and tribal names Bayat, Bayandur, Afshar, Kayi, and others. It started to be used as an ethnonym by Oguz tribes[5] that settled in Anatolia, Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan.

In Anatolia, since the late Middle Ages, "Turkoman" was supplanted by the term "Ottomans", which came from the name of the Ottoman Empire and its ruling dynasty. The term "Turkoman" has not been used in Azerbaijan since the 17th century, but it remained as the self-name of the semi-nomadic tribes of the Terekeme, a sub-ethnic group of the Azerbaijani people.[7]

In the early 21st century, this ethnonym is still used by the Turkmens of Central Asia—[8][9]the main population of Turkmenistan—Iran, Afghanistan and Russia, as well as Iraqi and Syrian Turkmens, the other descendants of the Oghuz Turks. "Turkoman", "Turkmen", "Turkman" and "Torkaman" were—and continue to be—used interchangeably.[10][11]

Etymology and history

The first-known mention of the term "Turkmen", "(Turkman)" or "Turkoman" occurs in Chinese texts of the 8th and 9th centuries as Тö-kü-möng, presumably in Zhetisu.[12] Use of the term "Turkoman" spread with the expansion of the area of residence of that part of the Oghuz that converted to Islam.

The greatest spread of the term "Turkoman" occurred in the era of the Seljuk conquests. Muslim Oghuz people rallied around the Kınık tribe that made up the core of the future Seljuk tribal union and the state they would create in the 11th century. Since the Seljuk era, the sultans of the dynasty created military settlements in parts of the Near and Middle East to strengthen their power; large Turkoman settlements were created in Syria, Iraq, and eastern Anatolia. After the Battle of Manzikert, the Oghuz extensively settled throughout Anatolia and Azerbaijan. In the 11th century, Turkomans densely populated Arran.[13] The 12th-century Persian writer al-Marvazi wrote; "Turkomans settled in Islamic countries and showed great character. So much so that they rule most of these lands, becoming kings and sultans .... Those who live in deserts and steppes and lead a nomadic lifestyle in summer and winter, they are the strongest of people and the most persistent in battle and war."[14]

Towards the high Middle Ages, the eastern part of Anatolia became known as "Turkomania" in European texts and as "Turkmeneli" in Ottoman sources. The center of the Turkoman settlement in the territory of modern-day Iraq became Kirkuk. The Turkmens also included the Ive and Bayandur tribes, from which the ruling clans of the states of Kara Koyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu emerged. After the fall of Aq Qoyunlu, the Turkoman tribes—partly under their own name, for example Afshars, Hajilu, Pornak, Deger, and Mavsellu—united in a single tribe of Turkoman or Qizilbash tribal confederation.[15]

Language

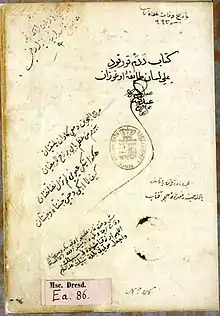

Turkomans primarily spoke languages that belong or belonged to the Oghuz branch of Turkic languages, which included the languages and dialects Seljuk, Old Anatolian Turkish, Ottoman Turkish, and Afshar Turkic. One of the languages spoken by Medieval Turkomans was used in the Oghuz Turks literary text "the Book of Dede Korkut". In the Gonbad manuscript—one of the earliest manuscripts that survive to this day— is of a mixed character and depicts vivid characteristics of the period of transition from later Old Oghuz Turkic to Early Modern Turkic of Iranian Azerbaijan. There are also orthographical, lexical and grammatical structures peculiar to Eastern Turkic.[16]

The following sentences are few of many wise-sayings that appear in the Book of Dede Korkut:[17]

|

|

Literature

Turkoman literature includes the famous Book of Dede Korkut, which was UNESCO's 2000 literary work of the year. It also includes the Oghuzname, Battalname, Danishmendname, Köroğlu epics, which are part of the literary history of Azerbaijanis, Turks of Turkey, and Turkmens. The modern and classical literature of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan are also considered Oghuz literature because it was produced by their descendants.

The Book of Dede Korkut is a collection of epics and stories bearing witness to the language, the way of life, religions, traditions and social norms of the Oghuz Turks. Other notable literary works of the Turkoman era include Târîh-i Âli Selçûk (History of the House of Seljuk) by Yazıcıoğlu Ali, Şikâyetnâme (شکايت نامه; "Complaint") by Fuzûlî, Dâstân-ı Leylî vü Mecnûn by Fuzûlî, Risâletü'n-Nushiyye by Yunus Emre, Mârifetnâme (معرفتنامه; "Book of Gnosis") by İbrahim Hakkı Erzurumi.[18]

Notable Turkoman dynasties and tribal confederations

Seljuq dynasty

Seljuqs were probably first to universally adopt a "Turkoman" ethnonym[19][20] (Turkmen)[21] and the quick spread of the term across the Islamic world is attested primarily to them. Seljuqs established both the Seljuk Empire and the Sultanate of Rum, which at their height stretched from Iran to Anatolia—the former being the first Turkic empire to link "the East and the West".[22][23]

Turkmen beyliks of Anatolia

Turkmen beyliks of Anatolia were small principalities in Anatolia governed by beys (rulers or lords), the first of which was founded at the end of the 11th century. A second, more extensive period of establishment of beyliks took place as a result of the decline of the Seljuq Sultanate of Rûm in the second half of the 1200s.

The basis of the organization of beyliks was the territorial and tribal principle. Unification took place around the chief of the tribe and his descendants. For this reason, the names of the beyliks were associated with the name of the dynasty rather than the territory; for example, Osmanoğullari, Dilmachoğullari, and Saruhanoğullari.[24]

The beylik of the Osmanoğlu, from its capital in Bursa, completed its conquest of other Turkmen beyliks by the late 15th century, becoming a transcontinental empire and a great power known as the Ottoman Empire.[25][26]

Kara Koyunlu

Kara Koyunlu was the union and tribal confederation of Oguz Turkic nomadic tribes that were led by the Shia Turkmen[27][28][29][30]dynasty from the Oghuz tribe Yiva, which existed in Asia Minor in the 14th-15th centuries on the territory of modern-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, Iraq, northwestern Iran, and eastern Turkey.

The Kara Koyunlu tribal confederation included the Turkmen tribes Baharlu, Saadlu, Karamanlu, Alpaut, Duharlu, Jagirlu, Hajilu, Agacheri.[31] The reign of Jahan Shah is generally considered as the most prosperous era of the Kara Koyunlu because it controlled vast and wealthy lands, becoming a formidable force in the region. Kara Koyunlu became one of the important Islamic states of that time, with a developed political, administrative, military, economic, and cultural structure.[32]

Ak Koyunlu

Ak Koyunlu was a confederation of Turkmen tribes[33][34] under the leadership of the Bayandur tribe,[35] who ruled eastern Anatolia and western Iran until the Safavids conquered the area between 1501 and 1503.[36]

The Ak Koyunlu first acquired land in 1402, when Turco-Mongol warlord Timur granted them all of Diyar Bakr in present-day Turkey. For a long time, these Turkmens were unable to expand their territory because the rival Kara Koyunlu Turkmens kept them at bay. The situation changed with the rule of Uzun Hasan, who defeated the Kara Koyunlu leader Jahān Shāh in 1467. After the defeat of the Timurid leader Abu Sa'id Mirza, Uzun Hasan was able to take Baghdad and territories around the Persian Gulf. He expanded into Iran as far east as Khorasan.[37]

Qizilbash

Qizilbash was initially the association of the Turkoman[38] nomadic tribes of Ustādjlu, Rūmlu, Shāmlu, Dulkadir, Afshār, Qājār, Takkalu, and others.[39] Later, the term Qizilbash was designated to all subjects of the Safavid state, regardless of their ethnicity. Among the Turks, however, the term began to be used to exclusively refer to Persians.[40]

The Qizilbash—some of whom contributed to the foundation of the Safavid dynasty of Iran—flourished in Iranian Azerbaijan,[41][42] Anatolia, and Kurdistan from the late-15th century.[43][44] As of 2020, there is an ethnic group known as the "Qizilbash" in Afghanistan. In Turkey, adherents of the Shia sect Ali-Illahi also include the Yoruk known as the Qizilbash. The Qizilbash also constitute part of the present-day Turkmens and Kurds tribes Belliqan, Milan, Balashaghi, Qurashli, and Qochkiri.[45]

Afsharid dynasty

The Afsharids were a short-lived dynasty that, at its height, controlled modern-day Iran, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, parts of the North Caucasus (Dagestan), Afghanistan, Bahrain, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, parts of Iraq, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman. It originated from the Turkmen Afshar tribe in Iran's north-eastern province of Khorasan.[46][47] The dynasty was founded in 1736 by the skilled military commander Nader Shah, who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty and proclaimed himself the Shah of Iran.[48]

During Nader's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sasanian Empire. After his death, most of the empire was divided between the Zands, Durranis, Georgians, and the Caucasian khanates, while Afsharid rule was confined to a small state in Khorasan. The Afsharid dynasty was overthrown by Mohammad Khan Qajar in 1796.

The military forces of the Afsharid dynasty had their origins in the relatively obscure, bloody, inter-factional violence in Khorasan during the collapse of the Safavid state. A small band of warriors under local warlord Nader Qoli of the Turkmen Afshar tribe in northeastern Iran comprised a few hundred men. At the height of Nader's power as the king of kings, Shahanshah, he commanded an army of 375,000, the most-powerful military force of its time,[49][50] which was led by one of the most talented and successful military leaders in history.[51]

Qajar dynasty

The Qajar dynasty was a royal dynasty of Turkoman[52][53] origin from the Qajar tribe; it ruled over Iran from 1789 to 1925. The Qajars were one of the original Turkmen Qizilbash tribes that emerged and spread across Asia Minor in the 10th and 11th centuries.[54] They later supplied military power to the Safavid Iran from the earliest days of the Safavids' reign. Numerous members of the Qajar tribe held important positions in Safavid Iran.{{cn}]

In 1794, a Qajar chieftain named Agha Mohammed, a member of the Qoyunlu branch of the Qajars, founded the Qajar dynasty, which took over the Zand dynasty in Iran. He started his campaign from his base south of the Caspian Sea, capturing Isfahan in 1785.[55] In 1786, Tehran acknowledged Mohammed's authority.[56] The Qajars had a desire to conquer new territories using the model of Genghis Khan and Timur; their goal was also to return the territories of the Safavid and Afsharid empires.[57] In the 1980s, the Qajar population was around 15,000 people, most of whom lived in Iran.

"Turkoman" ethnonym today

In Anatolia in the late Middle Ages, the term "Turkoman" was gradually supplanted by the term "Ottomans". The Ottoman ruling class identified themselves as Ottomans until the 19th century.[58] In the late 19th century, as the Ottomans adopted European ideas of nationalism, they preferred to return to a more common term "Turk" instead of "Turkoman", whereas previously "Turk" was used to exclusively refer to Anatolian peasants.[59]

The use of "Turkoman" as an ethnonym for the Turks living in Iranian Azerbaijan disappeared from common use after the 17th and 18th centuries. It continued to be used interchangeably with other ethno-historical terms for the Turkic people of the area, including Turk, Tatar, Ajam,[60] well into the early 20th century.[61] In the early 21st century, "Turkonan" remains as the self-name for the semi-nomadic tribes of the Terekime, a sub-ethnic group of the Azerbaijani people.[62]

In the early 21st century, the ethnonyms "Turkoman" and "Turkmen" are still used by the Turkmens of Turkmenistan,[63][64] who have sizeable groups in Iran,[65][66] Afghanistan,[67] Russia,[68] Uzbekistan,[69] Tajikistan[70] and Pakistan,[71] as well as Iraqi and Syrian Turkmens, descendants of the Oghuz Turks who mostly adhere to a Turkish heritage and identity.[72] Most Iraqi and Syrian Turkmens are the descendants of Ottoman soldiers, traders, and civil servants who were taken into Iraq from Anatolia during the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Turks of Israel[73] and Lebanon,[74] and Turkish sub-ethnic groups of Yoruks[75][76] and Karapapaks[77] are also referred to as Turkmens.[78][79]

References

- Karamustafa, A. (2020). "Who were the Türkmen of Ottoman and Safavid lands? An overlooked early modern identity". Der Islam. 97 (2): 477. doi:10.1515/islam-2020-0030.

- Barthold, V.V. Sochineniya; p. 558: “Whatever the former significance of the Oghuz people in the Eastern Asia, after the events of the 8th and 9th centuries, it focuses more and more on the West, on the border of the Pre-Asian cultural world, which was destined to be invaded by the Oghuz people in the 11th century, or, as they were called only in the west, by the Turkmen.”

- Yeremeyev, Dmitriy (1971). "Этногенез турок" [Ethnogenesis of the Turks]. Google Books (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

В конце XI в. в византийских хрониках впервые упоминаются туркмены, проникшие в Малую Азию. Анна Комнина называет их туркоманами. (At the end of the XI century, the Byzantine Chronicles mention for the first time Turkmens, who penetrated into Asia Minor. Anna Komnina calls them Turkomans.)

- Gerhard Doerfer, Iran'da Türkler (Turkish translation): It is very strange that the word “Turkmen” still leads to confusion; in Leningrad, I saw that Iraqi Oghuz literature was cataloged under the name "Turkmen"; in fact, the word Turkman simply means an Oghuz nomad.

- Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur, «Genealogy of the Turkmens» Commentary 132: Then the name "Turkmen" was assigned to one of the most powerful tribal associations - to the Oghuz people

- Clark, Larry (1998). Turkmen Reference Grammar. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 14. ISBN 3-447-04019-X. One of those dialects appears to have been spoken by the Karluk Turkmen, who were identified by Kashgari as "A tribe of the Turks. They are nomads, not Oghuz, but they are also Turkmen."

- Article "Terekimes»:«The term “terekem” is usually associated with the ethnonym “Turkmen”.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Turkmen-people

- https://bigenc.ru/ethnology/text/4211260 "Big Russian Encyclopedia"

- Barkey, Henri (2005). Turkey and Iraq: The Perils (and Prospects) of Proximity. Purdue University. p. 7.

- Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Encyclopedia. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2000. p. 1655. ISBN 0-87779-017-5.

- S. Agadzhanov. Essays on the history of the Oghuz and Turkmens of Central Asia of the 9th-13th centuries; Ed. Ilim, 1969; Archived copy of February 22, 2014 on Wayback Machine: “As mentioned earlier, part of the Oghuz and other Turks, mingling with the descendants of the ancient Indo-European population of Central Asia, were called as Turkmens. (In the Chinese sources of the VIII — beginning of the IX centuries, the country Tö-kü-möng, probably located in the Zhetisu area, is mentioned; the name of this country is probably associated with the name “Turkmen”). The name “Turkmen” appears mainly in the area of resettlement of the Oghuz who converted to Islam. ”

- P. Golden. The Turkic peoples and Caucasia, Transcaucasia, Nationalism and Social Change: Essays in the History of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, ed. by Ronald G. Suny; Michigan, 1996. pp. 45-67

- C. Hillenbrand, «Turkish Myth and Muslim Symbol», p. 148

- Encyclopaedia Iranika «AQ QOYUNLŪ»: "The surviving Āq Qoyunlū tribes and groups were absorbed, in some cases years later, into the Qizilbāš tribes; in this process, the Afšār retained their tribal identity while others, such as the Ḥāǰǰīlū, Döḡer, Mawṣellū, and Pornāk, were merged into a new tribe called Turkman".

- Mahsun Atsız, (2020), A Syntactic Analysis on Gonbad Manuscript of the Book of Dede Korkut, p. 189. "Another linguistic stratum, though restricted, can be determined as the orthographical, lexical and grammatical structures peculiar to Eastern Turkish. These Eastern Turkish features along with dialectal features evidently related to Turkish dialects of İran and Azerbaijan distinguish Gonbad manuscript from Dresden and Vatikan manuscipts."

- Mahsun Atsız, (2020), A Syntactic Analysis on Gonbad Manuscript of the Book of Dede Korkut, p. 192-195

- "Turkish Language and Literature". Turkish Cultural Foundation.

- Miers Elliot, Henry. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, Vol.2; Cambridge University Press; 2013. p. 164

- Griswold Goodrich, Samuel. Modern History: From the Fall of Rome, A.D. 476, to the Present Time; Morton and Griswold; 1848. p. 112 "Musaood, the successor of Mahmoud, was defeated 10 years after he came to the throne, by the Seljuk Turkomans in Khorasan... The Turkomans, who had emigrated or been driven from the steppes of Central Asia to the Bokhara plain, founded a dynasty as powerful as any that had yet sat on the throne of Persia."

- Bedirhan, Yaşar. Electronic Turkish Studies Vol. 9, Issue 4; 2014. pp. 165-185.

- P. Golden. The Turkic peoples and Caucasia, Transcaucasia, Nationalism and Social Change: Essays in the History of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, ed. by Ronald G. Suny; Michigan, 1996. pp. 45-67

- Alaev, L.B.; Ashrafyan, K.Z. (1994). History of the East. Vol. 2. The East in the Middle Ages. Eastern Literature, Russian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 5-02-018102-1.

- Tveritinova, A. S. Falsification of the history of medieval Turkey in Kemalist historiography; Byzantine time-book. Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR; 1953. T. VII. pp. 9-31.

- Quataert, Donald (2005). The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5.

- Matsuki, Eizo. "The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves" (PDF). Mediterranean Studies Group at Hitotsubashi University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Encyclopedia Iranica Subsequently, it came under the control of Turkmen dynasties like the Āq Qoyunlū and Qara Qoyunlū and then of local khanates like those of Qara Bāḡ and Naḵǰavān which formed a buffer region between the Ottomans and Safavids. “"

- Philippe, Beaujard (2019). The Worlds of the Indian Ocean. Chapter 17 - Western Asia: Revival of the Persian Gulf: Cambridge University Press. pp. 515–521. ISBN 9781108341219.CS1 maint: location (link) "In a state of demographic stagnation or downturn, the region was an easy prey for nomadic Turkmen. The Turkmen, however, never managed to build strong states, owing to a lack of sedentary populations (Martinez-Gros 2009: 643). When Tamerlane died in 1405, the Jalāyerid sultan Ahmad, who had fled Iraq, came back to Baghdad. Five years later, he died in Tabriz (1410) in a battle led against the Turkmen Kara Koyunlu (“[Those of the] Black Sheep”), who took Baghdad in 1412."

- "Kara Koyunlu". Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Kara Koyunlu, also spelled Qara Qoyunlu, Turkish Karakoyunlular, English Black Sheep, Turkmen tribal federation that ruled Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Iraq from about 1375 to 1468."

- The Book of Dede Korkut (F.Sumer, A.Uysal, W.Walker ed.). University of Texas Press. 1972. p. Introduction. ISBN 0-292-70787-8.

- Ryzhov, К. V. All monarchs of the world. The Muslim East. VII—XV centuries (in Russian) "Kara Koyunlu" section; Published by Veche; 2004.

- Nagendra Singh. International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties; Anmol Publications; 2002. p. 190

- "Ak Koyunlu". Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Ak Koyunlu, also spelled Aq Qoyunlu (“White Sheep”), Turkmen tribal federation that ruled northern Iraq, Azerbaijan, and eastern Anatolia from 1378 to 1508..."

- Türkmen Akkoyunlu İmparatorluğu: Türkmen Akkoyunlu İmparatorluğu makaleler antolojisi (in Turkish). Grafiker. 2003. p. 418. ISBN 9759272172.

- C.E. Bosworth and R. Bulliet, The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual , Columbia University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-231-10714-5, p. 275.

- C.E. Bosworth and R. Bulliet, The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual , Columbia University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-231-10714-5, p. 275.

- Vasiliev, L. S. History of the East, Late Medieval Iran. Safavid State; Archived by Wayback Machine

- David Blow. Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend. p. 165. "The primary court language remained Turkish. But it was not the Turkish of Istambul. It was a Turkish dialect, the dialect of the Qizilbash Turkomans..."

- Grigor'ev S.E. East: History and Culture, On the Shias of Afghanistan. Institute of Oriental Studies (Russian Academy of Sciences). St. Petersburg. The Qizilbash, originally consisting of representatives of seven Asia Minor Turkic tribes of Rumlu, Shamlu, Ustajlu, Afshar , Qajar, Tekkel and Dulkadir...

- Volkova, N.G. On the names of the Azerbaijanis in Caucasus, Onomastics of the East; Nauka (Science); 1980. p. 209. "In Turkish language, the term Qizilbash took a narrower meaning: that is how the Turks called the Persians".

- Cornell, Vincent J. (2007). Voices of Islam (Praeger perspectives). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 225 vol.1. ISBN 978-0275987329. OCLC 230345942.

- Parker, Charles H. (2010). Global Interactions in the Early Modern Age, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1139491419.

- Roger M. Savory: "Kizil-Bash". In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. 5, pp. 243–245.

- Savory, EI2, Vol. 5, p. 243: "Kizilbāsh (T. "Red-head"). [...] In general, it is used loosely to denote a wide variety of extremist Shi'i sects [see Ghulāt], which flourished in [V:243b] Anatolia and Kurdistān from the late 7th/13th century onwards, including such groups as the Alevis (see A. S. Tritton, Islam: belief and practices, London 1951, 83)."

- Shpazhnikov G. A. Religions of West Asian countries: The guide.; Nauka (Science), 1976. pp. 274-275

- Lockhart, L., "Nadir Shah: A Critical Study Based Mainly upon Contemporary Sources", London: Luzac & Co., 1938, 21 :"Nadir Shah was from a Turkmen tribe and probably raised as a Shiʿa, though his views on religion were complex and often pragmatic"

- Encyclopedia Iranica : "Born in November 1688 into a humble pastoral family, then at its winter camp in Darra Gaz in the mountains north of Mashad, Nāder belonged to a group of the Qirqlu branch of the Afšār Turkmen."

- Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant : "NADER SHAH, ruler of Persia from 1736 to 1747, embodied ruthless ambition, energy, military brilliance, cynicism and cruelty".

- Axworthy, Michael (2007). "The Army of Nader Shah". Iranian Studies. Informa UK. 40 (5): 635–646. doi:10.1080/00210860701667720. S2CID 159949082.

- Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, . I. B. Tauris

- Axworthy, Michael, "Iran: Empire of the Mind", Penguin Books, 2007. p158

- Daniel, Elton L., ed. (2002). Society and Culture in Qajar Iran: Studies in Honor of Hafez Farmayan. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1568591384.

- Floor, Willem M. (2008). Titles and Emoluments in Safavid Iran: A Third Manual of Safavid Administration, by Mirza Naqi Nasiri. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers. ISBN 978-1933823232.

- Fukasawa, Katsumi; Kaplan, Benjamin J.; Beaurepaire, Pierre-Yves (2017). Religious Interactions in Europe and the Mediterranean World: Coexistence and Dialogue from the 12th to the 20th Centuries. Oxon: Taylor & Francis. p. 280. ISBN 9781138743205.

- Black, Jeremy (2012). War in the Eighteenth-Century World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-230-37002-9.

- Black, Jeremy. War in the Eighteenth-Century World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2012. p. 141.

- Abbas Amanat, Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831-1896. p. 28

- (Kushner 1997: 219; Meeker 1971: 322)

- (Kushner 1997: 220–221)

- (in Turkish) Qarslı bir azərbaycanlının ürək sözləri. Erol Özaydın

- Baku, The City of the Governor (in Russian); Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary; Vol. 82; St. Petersburg; 1890—1907

- Article "Terekimes»: "The term 'terekem' is usually associated with the ethnonym 'Turkmen' ".

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Turkmen-people

- https://bigenc.ru/ethnology/text/4211260 "Big Russian Encyclopedia"

- "Ethnologue". Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- CIA World Factbook Iran

- "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Afghanistan: Turkmen".

- 2002 Russian census

- Alisher Ilhamov (2002). Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan. Open Society Institute: Tashkent.

- 2002 Tajikistani census (2010)

- Afghans in Quetta: Settlements, Livelihoods, Support Net works and Cross-Border Linkages

- Triana, María (2017), Managing Diversity in Organizations: A Global Perspective, Taylor & Francis, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-317-42368-3,

Turkmen, Iraqi citizens of Turkish origin, are the third largest ethnic group in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds and they are said to number about 3 million of Iraq's 34.7 million citizens according to the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- Suwaed, Muhammad (2015), "Turkmen, Israeli", Historical Dictionary of the Bedouins, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 237, ISBN 978-1442254510

- Orhan, Oytun (2010), The Forgotten Turks: Turkmens of Lebanon (PDF), ORSAM, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03

- Solak, İbrahim. XVI. Yüzyılda Maraş ve Çevresinde Dulkadirli Türkmenleri.

- Yusuf Durul: Flat-woven rugs made by "Yürüks". Ak Yayınları, 1977, page 60.

- Article "Terekimes»: "The term 'Terekem' is usually associated with the ethnonym 'Turkmen' ".

- İbrahim Aksu, "An Onomastic Study of Turkish Family Names, Their Origins, and Related Matters." 2005 , page 50.

- Insight Guides Turkey - Apa Publications (UK) Limited, 2015.

Further reading

- Kellner-Heinkele, Barbara (2000). "Türkmen". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 682–685. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.