Racism in Cuba

Racism in Cuba refers to racial discrimination against Cubans of Color. This group includes Afro-Cubans who are dark skinned and the only group on the island referred to as black and mulatos who are mixed race, have lighter skin and are most often not characterized as “black.” Race conceptions in Cuba are unique because of its long history of racial mixing and appeals to a "raceless" society. The Cuban census reports that 65% of the population is white while foreign figures report an estimate of the number of whites at anywhere from 40 to 45 percent.[1] This is likely due to the self-identifying mulatos who are sometimes designated officially as white.[2] Many Cubans argue that every Cuban has at least some African ancestry. Several pivotal events have impacted race relations on the island. Using the historic race-blind nationalism first established around the time of independence, Cuba has navigated the abolition of slavery, the suppression of black clubs and political parties, the revolution and its aftermath, and the current economic decline.

History

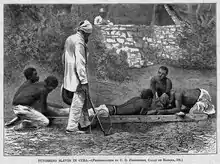

Slavery and Independence

According to Voyages – The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database,[3] about 900,000 Africans were brought to Cuba as slaves. To compare, some 470,000 Africans were brought to what is now the United States, and 5,500,000 to the much vaster region of what is now Brazil.

As slavery was abolished or restricted in other areas of the Americas during the 19th century, the Cuban slave trade grew dramatically. Just between 1790 and 1820, 325,000 Africans were brought to Cuba, quadruple the number from the people brought in the last 30 years.[4] The abolition of slavery was a gradual process that began during the first war for independence. On October 10 1868, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, a plantation owner, freed all of his slaves and asked them to join him in liberating Cuba from Spanish occupation.[5] There were many small rebellions in the next several decades which led Spain to counteract. Spanish propaganda convinced white Cubans that independence would only pave the way for a race war; That Afro-Cubans would take their revenge and conquer the island. At this time, many white colonists were terrified that the Haitian revolution would occur elsewhere, like in Cuba.[5][6][7] This fear of a black revolt painted perceptions about racial justice and stalled progress in race relations for the next several decades, if not still prevalent today.

In order to refute this claim, anti-racism activists and politicians of the time created the image of the loyal black soldier who existed only to serve the independence movement. This conception that painted Cubans of color as obedient, and single-mindedly in favor of independence was the opposite of the savage, sexually aggressive stereotype of Spanish propaganda. After this, whites were persuaded to think that because the independence movements helped to end slavery, that there was no reason for a black revolt; black people ought to be thankful for their freedom. And further, race was an invented obstacle according to the influential thinkers of the day. It was in these years that the ideas of Jose Martí or the words of General Antonio Maceo, “no whites nor blacks, but only Cubans” took hold on the island.[5][6] These two iconic figures represented black and white cooperation, and raceless Cuban patriotism. To this day, many Cubans argue that race as a concept only exists to divide; it isn’t real.[8] Following the abolition of slavery, Afro-Cubans joined the armed forces in droves to fight against the colonial occupation of Spain. At least half of all soldiers who fought in the wars for independence were Afro-Cuban.[9]

Partido Independiente de Color

In 1908, Evaristo Estenoz and Pedro Ivonet, two veterans from the independence wars, created the Partido Independiente de Color (Independent Party of Color, or PIC) which was the first Cuban political party established for non-white Cubans. In the aftermath of the Cuban war of independence, Afro-Cuban men, many of whom were veterans, expected a distinct shift in racial politics on the island after Spain was no longer in charge.[10] This was due especially to the substancial impact the Afro-Cuban community made to the war effort. In the subsequent decades, Afro-Cubans watched as white citizens and immigrants enjoyed economic stability while the black population grew more dissatisfied. Immigration was restricted to Spanish born persons in an effort to whiten (blanqueamiento) the island.[2][6] This was a measure heavily supported by the United States who had a vested interest in Cuba’s economic well being.

In response, and due to the race blind ideology of racial liberation created by Jose Marti and General Maceo, white Cubans were furious that a political party based on racial identity existed on the island. The PIC was called racist and exclusionary; they accepted white members but only elected black leaders to the party. The party was met with heavy backlash. Many white Cubans claimed that the establishment of a party based on race was itself racist. In 1910, Senator Martín Morúa Delgado, mulato himself, presented and helped to pass a law to ban race-based political parties, effectively outlawing the PIC.[11][12] The members of the PIC were not happy about this news. In 1912, Afro-Cubans took to the streets in armed protest against this law. Sources vary on the original organizers of the protest that occurred as a result of this ban. In response, President Machado ordered the military to end the rebellion, violently if necessary. Joined by private white militias, the national guard proceeded to kill between 3000-7000 Afro-Cubans, some of which were not involved in the uprising at all. This massacre, also called the little race war or war of 1912, cloaked the tone of race conversation for decades to come.

Cuban Revolution

The revolution of 1959 changed race relations drastically. Institutionally speaking, Cubans of Color benefited disproportionately from revolutionary reform. After the overthrow of the Batista regime, Fidel Castro established racism as one of the central battles of the revolution.[13] Though Cuba never had formal, state sanctioned segregation, privatization disenfranchised Cubans of color specifically.[12] Previously white only private pools, beaches, and schools were made public, free, and opened up to Cubans of all races and classes. Because much of the Afro-Cuban population on the island was impoverished before the revolution, they benefited widely from the policies for affordable housing, the literacy program, universal free education in general, and healthcare.[14] But above all, Castro insisted that the greatest obstacle for Cubans of color was access to employment. By the mid 1980's racial inequality on paper was virtually nonexistent. Cubans of color graduated at the same (or higher) rate as white Cubans. The races had an equal life expectancy and were equally represented in the professional arena.[12][15]

The revolutionary regime aligned itself with the race-blind narrative historically embedded in Cuba’s race relations. And because of this, Castro refused to enact laws that directly addressed and condemned race based persecution because he considered them unnecessary or even anti-Cuban. Instead, he believed that fixing economic structures for a better distribution of wealth would end racism. Castro's revolution also employed the use of the loyal black soldier of the independence days in order to curb white resistance to the new policies.[12] Scholars argue that raceless rhetoric left Cuba unprepared to address the deep seated culture of racism on the island. Two years after his 1959 speech at the Havana Labor Rally, Castro declared that the age of racism and discrimination was over. In a speech given at the Confederation of Cuban Workers in observance of May Day, Castro declared that the "just laws of the Revolution ended unemployment, put an end to villages without hospitals and schools, enacted laws which ended discrimination, control by monopolies, humiliation, and the suffering of the people."[16] After this announcement, any attempt by Afro-Cubans to open up discussion on race again was met with great resistance. If the regime claimed that racism was gone, an attempt to reignite the conversation on race was thus counterrevolutionary.

Special Period

With the reintroduction of capitalist practices to the island due to the fall of the Soviet Union and subsequent economic depression in the late 80's and early 90's, Afro-Cubans have found themselves at a disadvantage. Because the majority of those that emigrated from Cuba to the United States were middle class and white, Cubans of color still on the island were far less likely to receive remittances—dollars gifted from relatives in the United States.[2][7] With a free market came private businesses. The majority of which were from western countries with distinct racial biases of their own. Because of this, less Afro-Cubans were hired to work in the rising tourist sector. Hiring practices favored applicants with buena presencia, or good appearance, that adheres to European standards of beauty and respectability, therefore lighter-skinned or white Cubans were favored by foreign run establishments.[12] Similarly, in housing, despite improvements, racial difference persists due to various causes, such as inequality in house ownership inherited from before the revolution and black people's "lack of resources and connections."[12] The Afro-Cubans interviewed by Sawyer, even when they complained of racism and government policies, expressed their conviction that "things would be worse under the leadership of the Miami exile community or in the United States," and that "[t]he revolution has done so much for us." This "provide[s] Afro-Cubans with a reason to support the current regime."[17]

The Debate

There is heavy debate today on how the 1959 revolution impacted race relations on the island. Overall, the debate of racism in Cuba typically takes one of two extremes. Either the revolution ended racism, or it exacerbated or even created racial tension on the island.[13] Many scholars of race in Cuba take a far more qualifying position that while the revolution helped Afro-Cubans, it also halted any further racial progress beyond institutionalization.

The Revolution Ended Racism

Typically the proponents of the elimination of racism position are close to the revolutionary government, supportive of the revolution in total, and/or come from an older generation of Cubans that are more familiar with pre-revolutionary racism.[2][18] They argue that the dismantling of economic class through socialism destroyed the material perpetuation of racism.[19] In 1966, Castro himself said that, “Discrimination disappeared when class privileges disappeared."[7] Castro also often compared the anti-racism of Cuba to the United States' segregation, and labeled Cuba as a "Afro-Latin" nation when justifying anti-imperial support to liberation fronts in Africa.[2]

Many who argue that Cuba is not racist base their claims on the idea of Latin American Exceptionalism. According to this argument, a social history of intermarriage and mixing of the races is unique to Latin America. The large mestizo populations that result from high levels of interracial union common to the region are often linked to racial democracy. For many Cubans this translates into an argument of "racial harmony," often referred to as racial democracy. According to Mark Q. Sawyer, in the case of Cuba, ideas of Latin American Exceptionalism have delayed the progress of true racial harmony.[20]

The Revolution Silenced Cubans of Color

While many opponents of the revolution, such as Cuban emigrants, argue that Castro created race problems on the island, the most common claim for the exacerbation of racism is the revolution's inability to accept Afro-Cubans who want to claim a black identity.[19] After 1961, it was simply taboo to talk about race at all.[12] Antiracist Cuban activists who rejected a raceless approach and wanted to show pride in their blackness such as Walterio Carbonell and Juan René Betancourt in the 1960's, were punished with exile or imprisonment.[2][12]

Esteban Morales Domínguez, a professor in the University of Havana, believes that "the absence of the debate on the racial problem already threatens {...} the revolution's social project."[21] Carlos Moore, who has written extensively on the issue, says that "there is an unstated threat, blacks in Cuba know that whenever you raise race in Cuba, you go to jail. Therefore the struggle in Cuba is different. There cannot be a civil rights movement. You will have instantly 10,000 black people dead."[21] He says that a new generation of black Cubans are looking at politics in another way.[21] Cuban rap groups of today are fighting against this censorship; Hermanos de Causa explains the problem best by saying, "Don’t you tell me that there isn’t any [racism], because I have seen it/ don’t tell me that it doesn’t exist, because I have lived it."[22]

See also

References

- Carlos Moore. "Why Cuba's white leaders feel threatened by Obama".

- Schmidt, Jalane D. (2008). "Locked Together: The Culture and Politics of 'Blackness' in Cuba". Transforming Anthropology. 16 (2): 160–164. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7466.2008.00023.x. ISSN 1051-0559.

- Voyages – The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database Archived 2013-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Ferrer, Ada (2008). "Cuban Slavery and Atlantic Antislavery". Fernand Braudel Center Review. 31: 267–295 – via JSTOR.

- Ferrer, Ada (1999). Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868-1898. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Torre, Miguel A. De La (2018-05-04). "Castro's Negra/os". Black Theology. 16 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1080/14769948.2018.1460545. ISSN 1476-9948.

- Ravsberg, Fernando (2014). "Cuba's Pending Racial Debate". Afro-Hispanic Review. 33 (1): 203–204. ISSN 0278-8969.

- Benson, Devyn Spence (2016-04-25). Antiracism in Cuba. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-2672-7.

- Pérez, Louis A. (1986). "Politics, Peasants, and People of Color: The 1912 "Race War" in Cuba Reconsidered". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 66 (3): 509–539. doi:10.2307/2515461. ISSN 0018-2168.

- Helg, Aline (2009-04-20), "Cuba, Anti-Racist Movement and the Partido Independiente de Color", The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–5, ISBN 978-1-4051-9807-3, retrieved 2020-11-22

- Eastman, Alexander Sotelo (2019-02-23). "The Neglected Narratives of Cuba's Partido Independiente de Color: Civil Rights, Popular Politics, and Emancipatory Reading Practices". The Americas. 76 (1): 41–76. ISSN 1533-6247.

- Benson, Devyn Spence (2017-01-02). "Conflicting Legacies of Antiracism in Cuba". NACLA Report on the Americas. 49 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1080/10714839.2017.1298245. ISSN 1071-4839.

- de la Fuente, Alejandro (2001). "Building a Nation for All". A Nation for All: Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth-century Cuba. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 259–316. ISBN 978-0-8078-9876-5.

- Perez, Louis A.: Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, New York, NY. 2006, p. 326

- Weinreb, Amelia Rosenberg (2008). "Race,Fé(Faith) and Cuba's Future". Transforming Anthropology. 16 (2): 168–172. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7466.2008.00025.x. ISSN 1051-0559.

- Speech given by Fidel Castro on April 8, 1961. Text provided by Havana FIEL Network

- Sawyer, pp. 130–131

- de la Fuente, Alejandro (1995). "Race and Inequality in Cuba, 1899-1981". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (1): 131–168. ISSN 0022-0094.

- Lusane, Clarence (2003). "From Black Cuban to Afro‐Cuban:Researching Race in Cuba". Souls. 1 (2): 73–79. doi:10.1080/10999949909362164. ISSN 1099-9949.

- Mark Sawyer. Racial Politics in Post-Revolutionary Cuba.

- "A barrier for Cuba's blacks". Miami Herald.

- de la Fuente, Alejandro (2011). "The New Afro-Cuban Cultural Movement and the Debate on Race in Contemporary Cuba". Journal of Latin American Studies. 40 (4): 697–720. doi:10.1017/s0022216x08004720. ISSN 0022-216X.

Books and papers

- "Race and Inequality in Cuba Today" (Raza y desigualdad en la Cuba actual) by Rodrigo Espina and Pablo Rodriguez Ruiz

- "The Challenges of the Racial Problem in Cuba" (Fundación Fernando Ortiz) by Esteban Morales Dominguez

- Sujatha Fernandes, Fear of a Black Nation: Local Rappers, Transnational Crossings, and State Power in Contemporary Cuba, Anthropological Quarterly, Volume 76, Number 4, Fall 2003, pp. 575–608, E-ISSN 1534-1518 Print ISSN 0003-5491

- "Racism in Cuba: news about racism in Cuba in English and Spanish (2006- )"

- Revolution and race: Blacks in contemporary Cuba by Lourdes Casal (1979)

.svg.png.webp)