Rand Rebellion

The Rand Rebellion (Afrikaans: Rand-rebellie; also known as the 1922 strike) was an armed uprising of white miners in the Witwatersrand region of South Africa, in March 1922. Jimmy Green, a prominent politician in the Labour Party, was one of the leaders of the strike.

| Rand Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

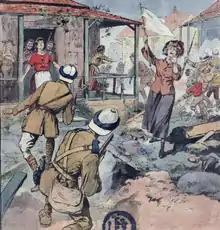

Contemporary depiction of the uprising | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 153 killed[1] | |||||||

Following a drop in the world price of gold from 130 shillings (£6 10s) per fine troy ounce in 1919 to 95s/oz (£4 15s) in December 1921, the companies tried to cut their operating costs by decreasing wages, and by weakening the colour bar to enable the promotion of racially cheapened black miners to skilled and supervisory positions.[2]

History

The rebellion started as a strike by white mine workers on 28 December 1921 and shortly thereafter, it became an open rebellion against the state. Subsequently the workers, who had armed themselves, took over the cities of Benoni and Brakpan, and the Johannesburg suburbs of Fordsburg and Jeppe.

The young Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) took an active part in the uprising on grounds of class struggle whilst reportedly opposing racist aspects of the strike,[3] as did the syndicalists. The racist aspect was typified by the slogan; "Workers of the world, unite and fight for a white South Africa!" and by several pogroms against blacks.[4]

Several Communists and syndicalists, the latter including the strike leaders Percy Fisher and Harry Spendiff, were killed as the rebellion was quelled by the Union Defence Force.[5] The rebellion was eventually put down by "considerable military firepower and at the cost of over 200 lives".[6]

Prime Minister Jan Smuts crushed the rebellion with 20,000 troops, artillery, tanks, and bomber aircraft. By this time the rebels had dug trenches across Fordsburg Square and the air force tried to bomb but missed and hit a local church. However, the army's bombardment finally overcame them.[7] Lieutenant Colonel Llewellyn Andersson's role in creating the Union Defence Force (South Africa) was instrumental in crushing the rebellion.[8]

Smuts' actions caused a political backlash, and in the 1924 elections his South African Party lost to a coalition of the National Party and Labour Party. They introduced the Industrial Conciliation Act 1924, Wage Act 1925 and Mines and Works Amendment Act 1926, which recognised white trade unions and reinforced the colour bar.[9] Under instruction from the Comintern, the CPSA reversed its attitude toward the white working class and adopted a new 'Native Republic' policy.[10][11]

In popular culture

A TV series in 8 episodes produced by the SABC in 1984 and entitled 1922, tells this part of South African history.

Bibliography

See also

References

- Bendix, S. (2001). Industrial relations in South Africa. Claremont: Juta. p. 59. ISBN 9780702152795.

- "Fifty fighting years – chapter 3". sacp.org.za.

- Baruch Hirson, The General Strike of 1922

- "South Africa Conflict in the 1920s - Flags, Maps, Economy, Geography, Climate, Natural Resources, Current Issues, International Agreements, Population, Social Statistics, Political System". workmall.com.

- V.I. Lenin. "Lenin: 703. TO G. Y. ZINOVIEV". marxists.org.

- Butler, A. 2004. Contemporary South Africa. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan

- "Battle of Fordsburg Square". blueplaques.co.za. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- The Times, 1/24/39, pg. 14

- Conflict in the 1920s, accessed June 2013

- Roux, E. R. (28 July 1928). "Thesis on South Africa, presented at the Sixth Comintern Congress". sahistory.org.za.

- Bunting, S. P. (23 July 1928). "Statement presented at the Sixth Comintern Congress". sahistory.org.za.