Regelation

Regelation is the phenomenon of ice melting under pressure and refreezing when the pressure is reduced. We can demonstrate regelation by looping a fine wire around a block of ice, with a heavy weight attached to it. The pressure exerted on the ice slowly melts it locally, permitting the wire to pass through the entire block. The wire's track will refill as soon as pressure is relieved, so the ice block will remain solid even after wire passes completely through. This experiment is possible for ice at −10 °C or cooler, and while essentially valid, the details of the process by which the wire passes through the ice are complex.[1] The phenomenon works best with high thermal conductivity materials such as copper, since latent heat of fusion from the top side needs to be transferred to the lower side to supply latent heat of melting. In short, the phenomenon in which ice converts to liquid due to applied pressure and then re-converts to ice once the pressure is removed is called regelation.

.jpg.webp)

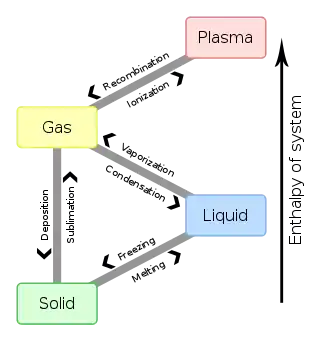

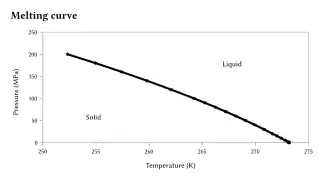

Regelation was discovered by Michael Faraday. It occurs only for substances such as ice, that have the property of expanding upon freezing, for the melting points of those substances decrease with the increasing external pressure. The melting point of ice falls by 0.0072 °C for each additional atm of pressure applied. For example, a pressure of 500 atmospheres is needed for ice to melt at −4 °C.[2]

Surface melting

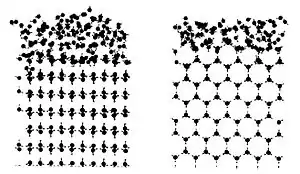

For a normal crystalline ice far below its melting point, there will be some relaxation of the atoms near the surface. Simulations of ice near to its melting point show that there is significant melting of the surface layers rather than a symmetric relaxation of atom positions. Nuclear magnetic resonance provided evidence for a liquid layer on the surface of ice. In 1998, using atomic force microscopy, Astrid Döppenschmidt and Hans-Jürgen Butt measured the thickness of the liquid-like layer on ice to be roughly 32 nm at −1 °C, and 11 nm at −10 °C.[3]

The surface melting can account for the following:

- Low coefficient of friction of ice, as experienced by skaters.

- Ease of compaction of ice

- High adhesion of ice surfaces

Examples of regelation

A glacier can exert a sufficient amount of pressure on its lower surface to lower the melting point of its ice. The melting of the ice at the glacier's base allows it to move from a higher elevation to a lower elevation. Liquid water may flow from the base of a glacier at lower elevations when the temperature of the air is above the freezing point of water.

Misconceptions

Ice skating is given as an example of regelation; however, the pressure required is much greater than the weight of a skater. Additionally, regelation does not explain how one can ice skate at sub-zero (°C) temperatures.[4]

Compaction and creation of snow balls is another example from old texts. Here, the pressure required is far greater than the pressure that can be applied by hand. A counter example is that cars do not melt snow as they run over it.

Latest progress

A supersolid skin that is elastic, hydrophobic, thermally more stable covers both water and ice. The skins of water and ice are characterized by an identical H-O stretching phonons of 3450 cm^-1. Neither the case of liquid forms on ice nor ice layer covers water, but the supersolid skin slipperizes ice and toughens the water skin[5]

Hydrogen bond (O:H-O) relaxation under compression. Compression shortens and stiffens the O:H nonbond and simultaneously lengthens and softens the H-O covalent bond, and negative pressure effect oppositely [6]

Melting point is proportional to the cohesive energy of the covalent bond. Therefore, compression lower the Tm.[7]

Further reading

- Y. Huang, X. Zhang, Z. Ma, Y. Zhou, W. Zheng, J. Zhou, and C.Q. Sun, Hydrogen-bond relaxation dynamics: resolving mysteries of water ice. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2015. 285: 109-165.

- C.Q. Sun, Relaxation of the Chemical Bond. Springer Series in Chemical Physics 108. Vol. 108. 2014 Heidelberg,807 pp. ISBN 978-981-4585-20-0.

References

- Drake, L. D.; Shreve, R. L. (1973). "Pressure Melting and Regelation of Ice by Round Wires". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 332 (1588): 51. Bibcode:1973RSPSA.332...51D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1973.0013. S2CID 137274632.

- Glossary of Meteorology: Regelation Archived 2006-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, American Meteorological Society, 2000

- Döppenschmidt, Astrid; Butt, Hans-Jürgen (2000-07-11). "Measuring the Thickness of the Liquid-like Layer on Ice Surfaces with Atomic Force Microscopy". Langmuir. 16 (16): 6709–6714. doi:10.1021/la990799w.

- White, James. The Physics Teacher, 30, 495 (1992).

- Zhang, Xi; et al. (October 2014). "A common superslid skin covering both water and ice" (PDF). Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 16 (42): 22987–22994. arXiv:1401.8045. Bibcode:2014PCCP...1622987Z. doi:10.1039/C4CP02516D. PMID 25198167. S2CID 5256149.

- Sun, Changqing (2014). Relaxation of the Chemical Bond. Springer. p. 807. ISBN 978-981-4585-20-0.

- Sun, Chang Qing; et al. (2012). "Hidden force opposing compression of ice". Chemical Science. 3: 1455–1460. arXiv:1210.1913. doi:10.1039/c2sc20066j. S2CID 97318835.