Relief of Goes

In August 1572, during the course of the Eighty Years' War, the city of Goes, in the Spanish Netherlands, was besieged by Dutch forces with the support of English troops sent by Queen Elizabeth I. This was a menace to the safety of the nearby city of Middelburg, also under siege. Given the impossibility of rescue of Goes by sea, 3,000 soldiers of the Spanish Tercios under the command of Cristóbal de Mondragón waded across the river Scheldt at its mouth, walking 15 miles overnight in water up to chest deep. The surprise arrival of the Tercios forced the withdrawal of the Anglo-Dutch troops from Goes, allowing the Spanish to maintain control of Middelburg, capital of Walcheren Island.

| Relief of Goes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

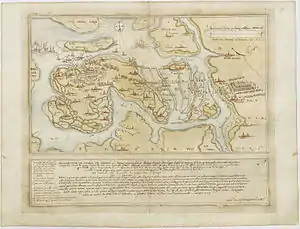

The Siege of Goes, 1572, by Petro Le Poivre. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000 | 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 800+ killed | 6 drowned | ||||||

Background

By 1566, in the Netherlands, at that time belonging to the Spanish Monarchy, a series of revolts emerged against the Spanish authorities, mainly caused by religious and economic impositions on the Dutch population. In 1567 the hostilities increased, leading to the Eighty Years' War.

In April 1572, the Sea Beggars, Dutch rebels opposed to Spain, took Brielle, the first city conquered during the war. Other cities in the province of Zeeland soon joined the rebels, and by mid-1572 only Arnemuiden and Middelburg, on the island of Walcheren, and Goes (also called Tergoes), on the island of Zuid-Beveland, remained under Spanish control, all of them besieged and threatened by the Dutch forces under Stadtholder William of Orange with the support of English troops sent by Elizabeth I.

Jerome Tseraarts, governor of Flushing in command of the Dutch forces on the island of Walcheren, had tried to capture Goes shortly before, having been repelled by the garrison of the city, commanded by Isidro Pacheco.[1] On 26 August 1572, in command of 7,000 soldiers[2] among which were 1,500 English under Thomas Morgan and Humphrey Gilbert,[1] and a fleet of 40 ships,[3] Tseraarts returned to besiege the city. The Spanish garrison of Goes, much inferior in number, would not withstand the siege for long without reinforcements.

Don Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba and Governor of the Netherlands on behalf of Philip II of Spain, ordered Sancho Dávila, Governor of Antwerp Citadel stationed in North Brabant, to send reinforcements to Goes by sea. The presence in the area of the fleet of the Sea Beggars under Ewout Pietersz Worst prevented it.[4]

Relief of Goes

.jpg.webp)

The river Scheldt was divided into two branches flowing in different directions before it disembogued into the North Sea: the Oosterschelde flowed to the north, the Westerschelde to the west. Between these two arms there were the islands of Walcheren and Zuid-Beveland, in the northern part of which laid Goes. The area between Brabant and Zuid-Beveland was largely a flat floodplain exposed to the tides of the North Sea and the river currents of the Scheldt, channels of which intersected the mudflats. When the tide went down the river channels had between 1 and 1.5 meters of depth, and when it rose the depth in the main channel reached three meters.

Captain Plomaert, a Fleming loyal to Spain, accompanied by two locals who knew the terrain well, studied the possibility of the Spanish troops fording the Oosterschelde on foot taking advantage of hours of low tide. Plomaert’s plan was presented to Sancho Dávila and Cristóbal de Mondragón, who accepted it as viable. For its execution Mondragón assembled a force of 3,000 Spanish, Walloon, and German pikemen of the Tercios at Woensdrecht (near Bergen op Zoom).[2]

On the evening of 20 October, Mondragón and his men, preceded by Plomaert and his guides, went into the river, each one equipped with a bag of gunpowder and provisions that they were to hold over the head or at the tip of their pikes throughout the crossing. During the night they crossed the fifteen miles of river channels and mudflats that separated them from the high dike on the opposite bank of the Scheldt, with water sometimes up to the chest, sinking into the muddy bottom, buffeted by the waves and currents of the river, and pressed by the imminent rising tide.

Shortly before dawn they reached the riverbank of Zuid-Beveland near Yerseke, at 20 km of Goes, having lost only nine men to drowning during the crossing of the river (a minute number of casualties compared to the danger of the task).[2] Then they moved toward Goes. The Anglo-Dutch troops besieging the city, surprised by the Tercios, which they had expected to arrive at some port of the island, abandoned the siege and began a hurried retreat to their ships, pursued by the soldiers of Mondragón, which overtook their rear, inflicting over 800 casualties.[5]

Consequences

The withdrawal of the Anglo-Dutch forces from Goes’s outskirts allowed the Spanish troops to temporarily relieve Middelburg, capital of Zeeland, which withstood the Dutch siege until its surrender in February 1574. At the end of 1572, Goes, Arnemuiden, Middelburg, and Rammekens remained under Spanish control. The island of Schouwen, including Zierikzee, was held by the Dutch forces until its recapture in 1576 by Luis de Requesens, the Governor of the Spanish Netherlands.

Notes

- Fissel p.137

- Motley p.345

- Rustant p.224

- Davies p.590

- Mariana p.CXXI

References

- Fissel, Mark Charles (2001). English warfare, 1511–1642; Warfare and history. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21481-0.

- Motley, John Lothrop. The Rise of the Dutch Republic, Entire 1566–74 .

- Davies, Charles Maurice (1841). History of Holland, from the beginning of the tenth to the end of the eighteenth century. 1. London, UK: J.W. Parker.

- de Mariana, Juan (1820). Historia general de España (in Spanish). XV. Madrid, Spain: Imp. de D. Leonardo Nuñez de Vargas.

- de Rustant, José Vicente (1751). Historia de don Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, (llamado comunmente El Grande) primero del nombre, duque de Alva: Escrita, y extractada de los mas veridicos autores (in Spanish). 2. Madrid, Spain: En la imprenta de don P.J. Alonso y Padilla.