Mutiny of Hoogstraten

The Mutiny of Hoogstraten (1 September 1602 – 18 May 1604) was the longest mutiny by soldiers of the Army of Flanders during the Eighty Years' War.[1] Frederick Van den Berg's attempt to end the mutiny by force, with a siege to recapture the town, ended in defeat at the hands of an Anglo-Dutch army under of Maurice of Nassau. After a period of nearly three years the mutineers were able either to join Maurice's army or rejoin the Spanish army after a pardon had been ratified.[2]

| Date | 1 September 1602 – 18 May 1604 |

|---|---|

| Location | Hoogstraten, Habsburg Netherlands |

| Also known as | the Union of Hoogstraten |

| Cause | arrears of pay |

| Participants | soldiers of the Army of Flanders |

Background

Maurice of Nassau had been actively campaigning against the Habsburg armies in the Southern Netherlands and took full advantage of Archduke Albert of Austria's preoccupation with the Siege of Ostend to capture several towns with royal garrisons in the Northern Netherlands.[3]

Maurice in his first objective successfully besieged and retook Rheinberg in July 1601. Between July and September 1602 the Spanish-held town of Grave was besieged and captured by the Dutch and English army led by Maurice and Francis Vere respectively.[4]

Mutiny and siege

| Siege of Hoogstraten | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War & the Anglo–Spanish War | |||||||

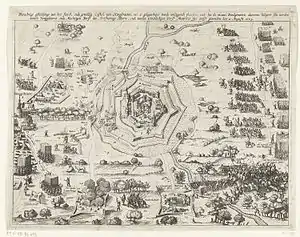

Relief of the mutineers of Hoogstraten by Maurice's army August 1603 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

14,000 3,000 mutineers | 9,800[6] | ||||||

After the failure to relieve the Spanish garrison at Grave and its subsequent surrender, morale plummeted in the Army of Flanders, some soldiers not having been paid in addition to provisioning being poor. A group of 3,000 disgruntled troops, mostly Italians and Spaniards, mutinied and took and fortified the little town of Hoogstraten.[7] From this secure position, the elected representatives of the mutineers were able to negotiate both with their own command and with the Dutch government.[6]

Count Maurice hoped to use the mutineers to his advantage yet at the same time understood their frustrations. While moving towards the town Maurice soon sighted an army.[8] This was the 10,000 troops under Frederik van den Bergh who had marched from Ostend collecting reinforcements on the way, including many Italians, hoping to recapture the town and shore up its defences. The two armies faced off while Maurice looked for a suitable town in which to garrison the mutineers, with neither side willing to risk losing the advantage.[8]

On August 3 Maurice moved into Hoogstraten much to the delight of the Spanish mutineers who even feted him during his short visit. Here he finally signed an agreement to protect them until they should be reconciled with Albert.[6] Realising Maurice's army had the upper hand and had the mutineers fully on their side, Van den Berg ordered his army to withdraw, also fearing that some of his men would even join them. Three days later the Anglo-Dutch vanguard caught the rear of Van den Berg’s retreating Spanish army.[5]

The mutineers went so far as to create their own state, the Republic of Hoogstraten, with green sashes to distinguish themselves from troops on both sides. Many of the mutineers eventually transferred to Dutch service after they were classed as outlaws by Spanish high command.[9]

When Maurice provided them with a cavalry force they became a bigger threat and it was only then that the Archduke decided to ratify a treaty that granted a complete pardon despite the protests of Spain and the council of state.[2]

Aftermath

When winter came in 1603 all parties retired to winter quarters and Maurice, true to his word, gave the mutineers the town of Grave to garrison.[5]

The mutiny had a severe effect on Spanish military operations, with the Archduke fearing that it might force the abandonment of the Siege of Ostend. During the Siege of Sluis the following year he was incapable of mounting any form of significant offensive to counter Maurice in the field.[2]

An important source for the organisation of the mutiny is the autobiography of Charles Alexandre de Croÿ, Marquis d'Havré, who was a hostage of the mutineers for eleven months.

References

- Olaf van Nimwegen, The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588-1688 (Woodbridge, Boydell Press, 2010), p. 39.

- Allen p 133

- Borman pp 230-32

- Dunthorne p 51

- The Field of Mars Volume 2 Being an Alphabetical Digestion of the Principal Naval and Military Engagements, in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, Particularly of Great Britain and Her Allies, from the Ninth Century to the Present Period. J. Macgowan. 1801.

- Motley, John Lothrop (1869). History of the United Netherlands from the death of William the silent to the Synod of Dort, with a full view of the English-Dutch struggle against Spain, and of the origin and destruction of the Spanish armada, Volume 4. Oxford University. pp. 120–21.

- Luc Duerloo, Dynasty and Piety: Archduke Albert (1598-1621) and Habsburg Political Culture in an Age of Religious Wars (Ashgate, 2013), p. 130.

- Allen123

- Parker p 170

- Bibliography

- Allen, Paul C (2000). Philip III and the Pax Hispanica, 1598–1621: The Failure of Grand Strategy. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07682-7.

- Borman, Tracy (1997). Sir Francis Vere in the Netherlands, 1589-1603: A Re-evaluation of His Career as Sergeant Major General of Elizabeth I's Troops. University of Hull.

- Charles Alexandre de Croÿ, Memoires geurriers de ce qu'y c'est passé aux Pays Bas, depuis le commencement de l'an 1600 iusques a la fin de l'année 1606 (Antwerp, Hieronymus Verdussen, 1642). Available on Google Books.

- Dunthorne, Hugh (2013). Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560-1700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521837477.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2004). The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567-1659: The Logistics of Spanish Victory and Defeat in the Low Countries' Wars Cambridge Studies in Early Modern History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521543927.