Renato Dulbecco

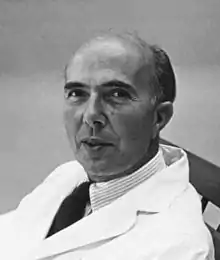

Renato Dulbecco (/dʌlˈbɛkoʊ/ dul-BEK-oh,[4][5] Italian: [reˈnaːto dulˈbɛkko, -ˈbek-]; February 22, 1914 – February 19, 2012)[6] was an Italian–American virologist who won the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on oncoviruses, which are viruses that can cause cancer when they infect animal cells.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] He studied at the University of Turin under Giuseppe Levi, along with fellow students Salvador Luria and Rita Levi-Montalcini, who also moved to the U.S. with him and won Nobel prizes. He was drafted into the Italian army in World War II, but later joined the resistance.

Renato Dulbecco | |

|---|---|

Dulbecco c.1966 | |

| Born | February 22, 1914 Catanzaro, Italy |

| Died | February 19, 2012 (aged 97) |

| Nationality | Italian, American[1] |

| Alma mater | University of Turin |

| Known for | Reverse transcriptase |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Virologist |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | Howard Temin[3] |

Early life

Dulbecco was born in Catanzaro (Southern Italy), but spent his childhood and grew up in Liguria, in the coastal city Imperia. He graduated from high school at 16, then moved to the University of Turin. Despite a strong interest in mathematics and physics, he decided to study medicine. At only 22, he graduated in morbid anatomy and pathology under the supervision of professor Giuseppe Levi. During these years he met Salvador Luria and Rita Levi-Montalcini, whose friendship and encouragement would later bring him to the United States. In 1936 he was called up for military service as a medical officer, and later (1938) discharged. In 1940 Italy entered World War II and Dulbecco was recalled and sent to the front in France and Russia, where he was wounded. After hospitalization and the collapse of Fascism, he joined the resistance against the German occupation.[13]

Career and research

After the war he resumed his work at Levi's laboratory, but soon he moved, together with Levi-Montalcini, to the U.S., where, at Indiana University, he worked with Salvador Luria on bacteriophages. In the summer of 1949 he moved to Caltech, joining Max Delbrück's group (see Phage group). There he started his studies about animal oncoviruses, especially of polyoma family.[15] In the late 1950s, he took Howard Temin as a student, with whom, and together with David Baltimore, he would later share the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for "their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumour viruses and the genetic material of the cell." Temin and Baltimore arrived at the discovery of reverse transcriptase simultaneously and independently from each other; although Dulbecco did not take direct part in either of their experiments, he had taught the two methods they used to make the discovery.[16]

Throughout this time he also worked with Marguerite Vogt. In 1962, he moved to the Salk Institute and then in 1972 to The Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now named the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute) where he was first appointed associate professor and then full professor.[17] As many Italian scientists Dulbecco did not have any PhD because it was not existent in the Italian higher education system (until when it was introduced in 1980[18]). In 1986 he was among the scientists who launched the Human Genome Project.[19][20] From 1993 to 1997 he moved back to Italy, where he was president of the Institute of Biomedical Technologies at C.N.R. (National Council of Research) in Milan. He also retained his position on the faculty of Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Dulbecco was actively involved in research into identification and characterization of mammary gland cancer stem cells until December 2011.[21] His research using a stem cell model system suggested that a single malignant cell with stem cell properties may be sufficient to induce cancer in mice and can generate distinct populations of tumor-initiating cells also with cancer stem cell properties.[22] Dulbecco's examinations into the origin of mammary gland cancer stem cells in solid tumors was a continuation of his early investigations of cancer being a disease of acquired mutations. His interest in cancer stem cells was strongly influenced by evidence that in addition to genomic mutations, epigenetic modification of a cell may contribute to the development or progression of cancer.

Nobel Prize

Dulbecco and his group demonstrated that the infection of normal cells with certain types of viruses (oncoviruses) led to the incorporation of virus-derived genes into the host-cell genome, and that this event lead to the transformation (the acquisition of a tumor phenotype) of those cells. As demonstrated by Temin and Baltimore, who shared the Nobel Prize with Dulbecco, the transfer of viral genes to the cell is mediated by an enzyme called reverse transcriptase (or, more precisely, RNA-dependent DNA polymerase), which replicates the viral genome (in this case made of RNA) into DNA, which is later incorporated in the host genome.

Oncoviruses are the cause of some forms of human cancers. Dulbecco's study gave a basis for a precise understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which they propagate, thus allowing humans to better fight them. Furthermore, the mechanisms of carcinogenesis mediated by oncoviruses closely resemble the process by which normal cells degenerate into cancer cells. Dulbecco's discoveries allowed humans to better understand and fight cancer. In addition, it is well known that in the 1980s and 1990s, an understanding of reverse transcriptase and of the origins, nature, and properties of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, of which there are two well-understood serotypes, HIV-1, and the less-common and less virulent HIV-2), the virus which, if unchecked, ultimately causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), led to the development of the first group of drugs that could be considered successful against the virus, the reverse-transcriptase inhibitors, of which zidovudine is a well-known example. These drugs are still used today as one part of the highly-active antiretroviral therapy drug cocktail that is in contemporary use.

Other awards

In 1965 he received the Marjory Stephenson Prize from the Society for General Microbiology. In 1973 he was awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University together with Theodore Puck and Harry Eagle. Dulbecco was the recipient of the Selman A. Waksman Award in Microbiology from the National Academy of Sciences in 1974.[23] He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1974.[2]

He died three days before his 98th birthday.

References

- Dulbecco is a naturalized American citizen. See Dulbécco, Renato in www.treccani.it

- "Fellowship of the Royal Society 1660-2015". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 2015-10-15.

- Dulbecco, R. (1995). "Howard M. Temin. 10 December 1934-9 February 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 41 (4): 471–80. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1995.0028. PMID 11615362.

- "Dulbecco". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- "Dulbecco". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Gellene, Denise (February 20, 2012). "Renato Dulbecco, 97, Dies; Won Prize for Cancer Study". New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1975". Nobelprize.org. 12 Sep 2012

- Verma, I. M. (2012). "Renato Dulbecco (1914–2012) Molecular biologist who proved that virus-derived genes can trigger cancer". Nature. 483 (7390): 408. doi:10.1038/483408a. PMID 22437605.

- Eckhart, W. (2012). "Renato Dulbecco: Viruses, genes, and cancer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (13): 4713–4714. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.4713E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203513109. PMC 3323998.

- Raju, T. N. (1999). "The Nobel chronicles. 1975: Renato Dulbecco (b 1914), David Baltimore (b 1938), and Howard Martin Temin (1934-94)". Lancet. 354 (9186): 1308. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)76086-4. PMID 10520671. S2CID 54316919.

- Kevles, D. J. (1993). "Renato Dulbecco and the new animal virology: Medicine, methods, and molecules" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 26 (3): 409–442. doi:10.1007/bf01062056. PMID 11613167. S2CID 36014355.

- Baltimore, D. (2012). "Retrospective: Renato Dulbecco (1914-2012)". Science. 335 (6076): 1587. doi:10.1126/science.1221692. PMID 22461601. S2CID 206541174.

- Nobel autobiography of Dulbecco

- Renato Dulbecco telling his story at Web of Stories

- Dulbecco, R (1976). "From the molecular biology of oncogenic DNA viruses to cancer". Science. 192 (4238): 437–40. Bibcode:1976Sci...192..437D. doi:10.1126/science.1257779. PMID 1257779. S2CID 6390065.

- Judson, Horace (2003-10-20). "No Nobel Prize for Whining". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1975".

- "Dottorato, Enciclopedia Treeccani".

- Dulbecco, R (1986). "A turning point in cancer research: Sequencing the human genome". Science. 231 (4742): 1055–6. Bibcode:1986Sci...231.1055D. doi:10.1126/science.3945817. PMID 3945817.

- Noll, H. (1986). "Sequencing the Human Genome". Science. 233 (4760): 143. Bibcode:1986Sci...233..143N. doi:10.1126/science.233.4760.143-b. PMID 3726524.

- Zucchi, I.; Sanzone, S.; Astigiano, S.; Pelucchi, P.; Scotti, M.; Valsecchi, V.; Barbieri, O.; Bertoli, G.; Albertini, A.; Reinbold, R. A.; Dulbecco, R. (2007). "The properties of a mammary gland cancer stem cell". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (25): 10476–10481. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410476Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703071104. PMC 1965538. PMID 17566110.

- Zucchi, I.; Astigiano, S.; Bertalot, G.; Sanzone, S.; Cocola, C.; Pelucchi, P.; Bertoli, G.; Stehling, M.; Barbieri, O.; Albertini, A.; Scholer, H. R.; Neel, B. G.; Reinbold, R. A.; Dulbecco, R. (2008). "Distinct populations of tumor-initiating cells derived from a tumor generated by rat mammary cancer stem cells" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (44): 16940–16945. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10516940Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808978105. PMC 2575224. PMID 18957543.

- "Selman A. Waksman Award in Microbiology". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

External links

- Renato Dulbecco on Nobelprize.org