Richmond Shakespear

Sir Richmond Campbell Shakespear (11 May 1812 – 16 December 1861) was an Indian-born British Indian Army officer. He helped to influence the Khan of Khiva to abolish the capture and selling of Russian slaves in Khiva.[2][3] This likely forestalled the Russian conquest of the Khiva, although it ultimately did not prevent it.

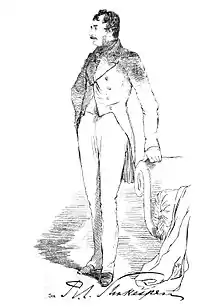

Richmond Shakespear | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Colesworthey Grant | |

| Born | 11 May 1812 West Bengal |

| Died | 16 December 1861 Indore |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | British East India army |

| Years of service | 1827–1861 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-Colonel[1] |

| Battles/wars | First Anglo-Afghan War, Second Anglo-Sikh War, Battle of Jellalabad, Battle of Ramnagar, Battle of Chillianwala, Battle of Gujrat[1] |

| Awards | Punjab Medal Companion of the Bath |

Background

Richmond Shakespear came from a family with deep ties to British activities in Asia. While his ancestors were rope-makers hailing from Shadwell (where there was a ropewalk named after them, Shakespear's Walk), by the seventeenth century, the Shakespears were involved in British military and civil service in Asia, and eventually raising families in India, although the children were still educated in England.[4]

Richmond Shakespear was the youngest son of John Talbot Shakespear and Amelia Thackeray, who both served in the Bengal Civil Service. Amelia was the eldest daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray (I), the grandfather of the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray (II). He was born in India on 11 May 1812, educated at the Charterhouse School, and entered Addiscombe Military Seminary in 1827. He gained a commission as Second Lieutenant for the Bengal Artillery in 1828, and moved back to India in 1829. He was positioned in various stations in Bengal until 1837, when he became Assistant at Gorakhpur.[1]

Intervention in Khiva

In 1839, he became Political Assistant to the British Mission to Herat, with his main duty as artillery instruction. He was sent by his commander, Major d'Arcy Todd, to negotiate with the Khan of Khiva for the release of the Russian captives held there; which the British worried might provoke a Russian invasion. Shakespear was successful in negotiations and marched to Orenburg with 416 Russian men, women, and children.[5] Because of this accomplishment, he was posted to Moscow and St. Petersburg where he was received by Tsar Nicholas I. When he returned to London, he was knighted by Queen Victoria on 31 August 1841.[1]

After Khiva

In 1842, Shakespear became Secretary to Major General George Pollock, who was commanding forces in Peshwar for the relief of Sir Robert Sale at Jalalabad. In 1843, he was appointed Deputy Commissioner of Sagar, and promoted to Brevet Captain. Later that year, he was transferred to Gwalior, where he was promoted to Regimental Captain in 1846, and where he remained until 1848.

Between 1848 and 1849, he served in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. For his services he received the Punjab Medal.[1]

Civil duties

Shakespear returned to civil duties in Gwalior toward the end of 1849. For the next ten years, he continued to advance in political and military roles in the British Raj, culminating in his appointment as Agent to the Governor-General for Central India. He became a Companion of the Bath in 1860.

He died on 16 December 1861 from bronchitis, and was survived by his wife, six daughters, and three sons.[1] His youngest son was John Shakespear (1861–1942).

References

- "Archive of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, Shakespear, Sir, Richmond Campbell, 1812–1861". Archive of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs.

- "Person Page".

- Aberigh Mackay, George R. (1875). Notes on Western Turkistan: Some Notes on the Situation in Western Turkistan. General Books LLC. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-154-79973-6.

- "Archive of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, Shakespear Family". Archive of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs.

- Ratliff, Walter R. (January 2010). Pilgrims on the Silk Road: A Muslim-Christian Encounter in Khiva. Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-60608-133-4.