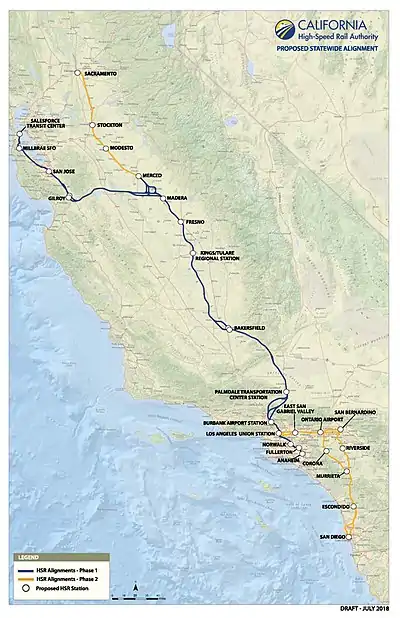

Route of California High-Speed Rail

The California High-Speed Rail system will be built in two phases. Phase 1 will be about 520 miles (840 km) long, and is planned to be completed in 2033, connecting the downtowns of San Francisco, Los Angeles using high-speed rail through the Central Valley with feeder lines served at Merced and an extension to Anaheim. In Phase 2, the route will be extended in the Central Valley north to Sacramento, and from east through the Inland Empire and then south to San Diego. The total system length will be about 800 miles (1,300 km) long.[1] Phase 2 currently has no timeline for completion.

Phase 1

San Francisco to San Jose

The 51-mile (82 km)[2] bookend from San Francisco to San Jose used by Caltrain is scheduled to be electrified by 2022. High-speed trains will run at 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) on shared tracks as far as the San Francisco 4th and King Street station starting in 2031, a few years after the completion of the Central Valley segment. Service is planned to be extended to the Transbay Transit Center once the Downtown Rail Extension is completed.[3] The one-way fare between San Francisco and San Jose is expected to cost $22 in 2013 dollars.[4]

The Authority recognizes the value of adding this link as soon as possible to the Initial Operating Segment (IOS), and is exploring ways of obtaining additional funding for it.[5]

San Jose to Merced / the Diablo Range crossing

The 125 miles (201 km) from San Jose to Merced, crossing the Pacheco Pass, will run at top speed on dedicated HSR tracks (since the current right-of-way south of Tamien is freight-owned). This segment runs through the Chowchilla Wye. This is included in the IOS, with a service start date per the 2015 Business Plan. [6]

One issue initially debated was the crossing of the Diablo Range via either the Altamont Pass or the Pacheco Pass to link the Bay Area to the Central Valley. On November 15, 2007, Authority staff recommended that the High-Speed Rail follow the Pacheco Pass route because it is more direct and serves both San Jose and San Francisco on the same route, while the Altamont route poses several major engineering obstacles, including crossing San Francisco Bay. Some cities along the Altamont route, such as Pleasanton and Fremont, opposed the Altamont route option, citing concerns over possible property taking and increase in traffic congestion.[7] However, environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, have opposed the Pacheco route because the area is less developed and more environmentally sensitive than Altamont.[8]

Some people are concerned with the Valley route, in particular its going down the east side of the Central Valley rather than the more open west side. Citizens for California High-Speed Rail Accountability note: "Environmental lawsuits against the California High-Speed Rail Authority often claim inadequate consideration of running the track next to Interstate 5 in the Central Valley or next to Interstate 580 over the Altamont Pass."[9]

The Pacheco Pass alignment going through the Grasslands Ecological Area, has been criticized by two environmental groups; The Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council.[10] A coalition that includes the cities of Menlo Park, Atherton, and Palo Alto has also sued the Authority to reconsider the Altamont Pass alternative.[11][12] More than one hundred land owners along the proposed route have rejected initial offers by the Authority, and the Authority has taken them to court, seeking to take their land through eminent domain.[13][14][15] The possibility of urban sprawl into communities along the route have been raised by farming industry leaders.[16]

On December 19, 2007, the Authority Board of Directors agreed to proceed with the Pacheco Pass option.[17] Pacheco Pass was considered the superior route for long-distance travel between Southern California and the Bay Area, although the Altamont Pass option would serve as a good commuter route. The Authority plans conventional rail upgrades for the Altamont corridor, to complement the high-speed project.

This segment will also cross the Calaveras Fault.

Merced to Fresno / the Chowchilla Wye

The current IOS does not include the portion northward from the Chowchilla Wye. The Authority is seeking additional funds to include it in the IOS, but if it does not obtain those it will construct the rest of the IOS without it. The service start date is 2025.[5]

The entire 60-mile (97 km) segment from Merced to Fresno in the Central Valley will run on dedicated HSR tracks. This segment also includes the Chowchilla Wye.[18] The southern portion of this segment (north of Madera to Fresno) has already received route approval and is undergoing construction.

The Chowchilla Wye is located between Gilroy and the main HSR line running between Merced and Fresno in the Central Valley. The wye has two purposes. One is to be able to take trains coming from the Bay Area and turn them to go towards Sacramento, and vice versa. The other is to allow a train to reverse itself on the tracks (that is, to swap the ends). However, since one of the train specifications is that they be able to have cabs at each end and run in both directions, the need to reverse trains is greatly reduced.

South of the Wye a new station has been proposed for Madera, and is included in the 2016 Business Plan.

Fresno to Bakersfield

This segment includes stations at Fresno, Kings–Tulare, and Bakersfield, as well as crossings of the Kings River, Cross Creek, and the Kern River.[19]

The 114-mile (183 km) segment in the Central Valley will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the Initial Operating Section in 2025. As of 7 May 2014, the route for this segment has been chosen and approved by the California High-Speed Rail Authority.[20] Final route approval was obtained by the Federal Railroad Administration and the federal Surface Transportation Board in August 2014, so construction can proceed.[21] Note that due to disputes with the cities of Shafter and Bakersfield, the currently planned segment ends north of Shafter until final routes through Shafter and northern Bakersfield are negotiated with those cities. (Refer to the Initial Construction Section (ICS) above.)

The CHSRA will build a private underpass for E.J. Dejong’s dairy farm.[22]

Bakersfield to Palmdale / the Tehachapi Mountains crossing

The 75 miles (121 km) from Bakersfield to Palmdale, crossing the Tehachapi Pass, will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the completed Phase 1 project in 2029.[6]

In January 2012, the Authority released a study, started in May 2011, that favors a route over the Tehachapi Pass into Antelope Valley and Palmdale over one that parallels Interstate 5 from San Fernando Valley over the Tejon Pass into the Central Valley.[23] The route over the Tehachapi Mountains is still to be determined.

The low point on Tehachapi Pass is 4,031 feet (1,229 m). This is significantly higher than Pacheco Pass at 1,368 feet (417 m) over the Diablo Range, and so this is a more formidable engineering challenge. For comparison, the route over Pacheco Pass begins in Chowchilla (elevation 240 feet (73 m)), crosses the valley floor and climbs to the pass (elevation 1,368 feet (417 m)), and descends to Gilroy (elevation 200 feet (61 m)). The route over the Tehachapi Pass begins in Bakersfield (elevation 404 feet (123 m)), crosses the valley floor and climbs over steeper mountains to the pass (elevation 4,031 feet (1,229 m)), then descends to Palmdale (elevation 2,657 feet (810 m)).

Community meetings to solicit stakeholder concerns were held around the end of 2015.[24]

If approved, a 2020 proposed Tehachapi route would destroy a homeless shelter, part of the Pacific Crest Trail, a historic Denny's restaurant, 34 family homes, 164 apartments, 55 mobile homes, a church, the R. Rex Parris High School, 175 farm fields, 311 businesses, and eight motels.[25]

Palmdale to Burbank / the San Gabriel Mountains crossing

The segment from Palmdale to Burbank will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the completed Phase 1 project in 2029.[6] This segment will cross the San Gabriel Mountains.

The basic route from Palmdale (elevation 2,657 feet (810 m), north of the San Gabriel Mountains) to Burbank (elevation 607 feet (185 m), south of the San Gabriel Mountains) is still under discussion. There are two major route alternatives. The one initially considered, called the "State Route 14 Corridor", ran from Palmdale in the Antelope Valley, then cross Soledad Pass, descend into the Santa Clarita Valley to Burbank in the San Fernando Valley, a distance of about 51 miles (82 km). More recently, two options are being considered for running under the mountains to the east of that route, the Angeles National Forest, a distance of about 35 miles (56 km).[26][27]

There is significant opposition by Santa Clarita Valley residents to the initial route,[28] and the under-the-mountains route would reduce travel time by about eight minutes, but would have additional Federal approval complications. There are still community stakeholder meetings proceeding, and as might be expected, there are also those who oppose the East Corridor alternative as well.[29]

On Thursday, May 28, 2015 the CHSRA held an open house meeting in the City of San Fernando to discuss the route into the Valley and the impacts of the proposed rail service, and found opposition by angry protesters, including city officials. Residents and officials of other affected cities in the Valley also have serious concerns. The Authority says it is committed to making this work, and to involving the communities to select the best route, but there are many factors to consider in selecting the route. Michelle Boehm, the Southern California section director of the project, said that the route would be selected over the next 12 to 18 months, and issue a final environment report in two years. The next community meeting will be in downtown Los Angeles on June 9, and is also expected to draw many protesters.[30]

The Palmdale to Burbank route and environmental considerations presentation (May 2015, PDF)] is available. The alternatives analysis is not due until the summer of 2015, and the route decision is not expected until 2016.[31]

Proposed routes for the Palmdale-to-Burbank section are displayed and explained in a 26-minute Virtual Open House presentation. This not only displays the factors taken into account to create the proposed routes, there is a virtual flyover of the proposed routes, and scenes from the many community meetings which illustrate the public outreach efforts underway (May–June 2015).

Phase 2

| External images | |

|---|---|

There has been route planning for Phase 2, but no dates and no financing plans have been made. Proposition 1A requires that Phase 1 be completed before construction is started on Phase 2. The Phase 2 segments, Merced–Sacramento and Los Angeles–San Diego, total about 280 miles (450 km). The completed system length after these extensions are constructed will be about 800 miles (1,300 km).

Los Angeles to San Diego

San Diego is considering how high-speed rail can play a role in their transportation options as Lindbergh Field is expected to reach maximum capacity between 2025 and 2030. A stop has been proposed at the north end of airport in conjunction with a new transit center. Airport consultant suggest that the train could provide an alternative for California destinations such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento and Ontario.[34]

References

- "2012 Business Plan | Business Plans | California High-Speed Rail Authority". Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- "Appendix L. Conceptual Cost Estimates" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- Thadani, Trisha (10 July 2020). "Plan for high-speed rail rolls out for San Francisco to San Jose - but with little cash". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "2014 Business Plan Ridership and Revenue Technical Memorandum" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Statement of Dan Richard : Chairman of the California High-Speed Authority Board of Directors : Hearing on "Continued Oversight of California High-Speed Rail"" (PDF). Transportation.house.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "2016 BUSINESS PLAN : MAY 1, 2016 : Connecting and Transforming California" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "California High Speed Rail Authority - State of California" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- Michael Cabanatuan (November 15, 2007). "High Speed Rail Authority staff advises Pacheco Pass route to L.A." The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- "TEN THINGS YOU DIDN'T KNOW ABOUT CALIFORNIA HIGH-SPEED RAIL (OUT OF THOUSANDS OF THINGS ALMOST NO ONE KNOWS)". Citizens for California High Speed Rail Accountability (CCHSRA). April 18, 2014.

- "Enviro Groups Rally Against Fast-Tracking California High-Speed Rail". The Heartland Institute. July 16, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- "Setback for HSR in San Jose to San Francisco Environmental Analysis". Planetizen. November 13, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- "Altamont". TRANSDEF. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- "Property rights battles threaten to further slow California's costly, long awaited bullet train project". FoxNews. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Vartabedian, Ralph (14 March 2015). "Ready to fight: Some growers unwilling to lose land for bullet train". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Sheehan, Tim (23 August 2014). "Land deals slowing California high-speed rail plan". The Fresno Bee. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Vartabedian, Ralph (24 February 2015). "Critics fear bullet train will bring urban sprawl to Central Valley". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "State Picks Pacheco Pass For High-Speed Rail". CBS 13. Associated Press. February 9, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- California, State of. "Merced to Fresno Project Section - Statewide Rail Modernization - Programs - California High-Speed Rail Authority". Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "California High-Speed Train Project Final EIR/EIS: Fresno to Bakersfield Section: Appendix 3.8-B Summary of Hydraulic Modeling for Project Alternatives" (PDF). California High-Speed Rail Authority. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- "High-Speed Rail Authority approves Fresno-Bakersfield section | abc30.com". Abclocal.go.com. 2014-05-07. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- Weikel, Dan (August 12, 2014). "Central Valley bullet train construction gets federal go-ahead". Los Angeles Times.

- Bowden, Bridgit; Johnson, Shawn (2019-09-18). "The High-Speed Rail Debate Persists In California". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- "California HSR Authority releases study". Railway Age. January 10, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "High-Speed Rail from Bakersfield to Palmdale - Story". Kerngoldenempire.com. Nexstar Media Group. May 4, 2015. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-02-29/bullet-train-plan-for-tehachapi-mountain-passage-would-cost-18-billion-over-82-miles

- "Palmdale to Burbank Section 2014 Scoping Report" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- Vartabedian, Ralph (January 23, 2016). "Bullet train project: Southern California segment might be built last, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "UPDATE: SCV residents give loud and clear message against high-speed rail". Signalscv.com. 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- "Residents express concerns over high-speed rail through Angeles National Forest". abc7.com. 2015-01-14. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- Vartabedian, Ralph (May 30, 2015). "San Fernando leaders confront state officials over bullet train route". Los Angeles Times.

- "PALMDALE TO BURBANK PROJECT SECTION UPDATE" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- "Burbank to Los Angeles Section 2014 SCOPING REPORT" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- "Los Angeles to Anaheim Project Section". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- Hawkins, Robert J. (January 26, 2011). "One solution for airport overcrowding? High speed rail". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 26 March 2016.