Royal Artillery Barracks, Woolwich

The Royal Artillery Barracks at Woolwich in the Royal Borough of Greenwich, London, was the home of the Royal Artillery from 1776 until 2007.

| Royal Artillery Barracks | |

|---|---|

| Woolwich | |

At 329m the south elevation constitutes the longest continuous architectural composition in London[1] | |

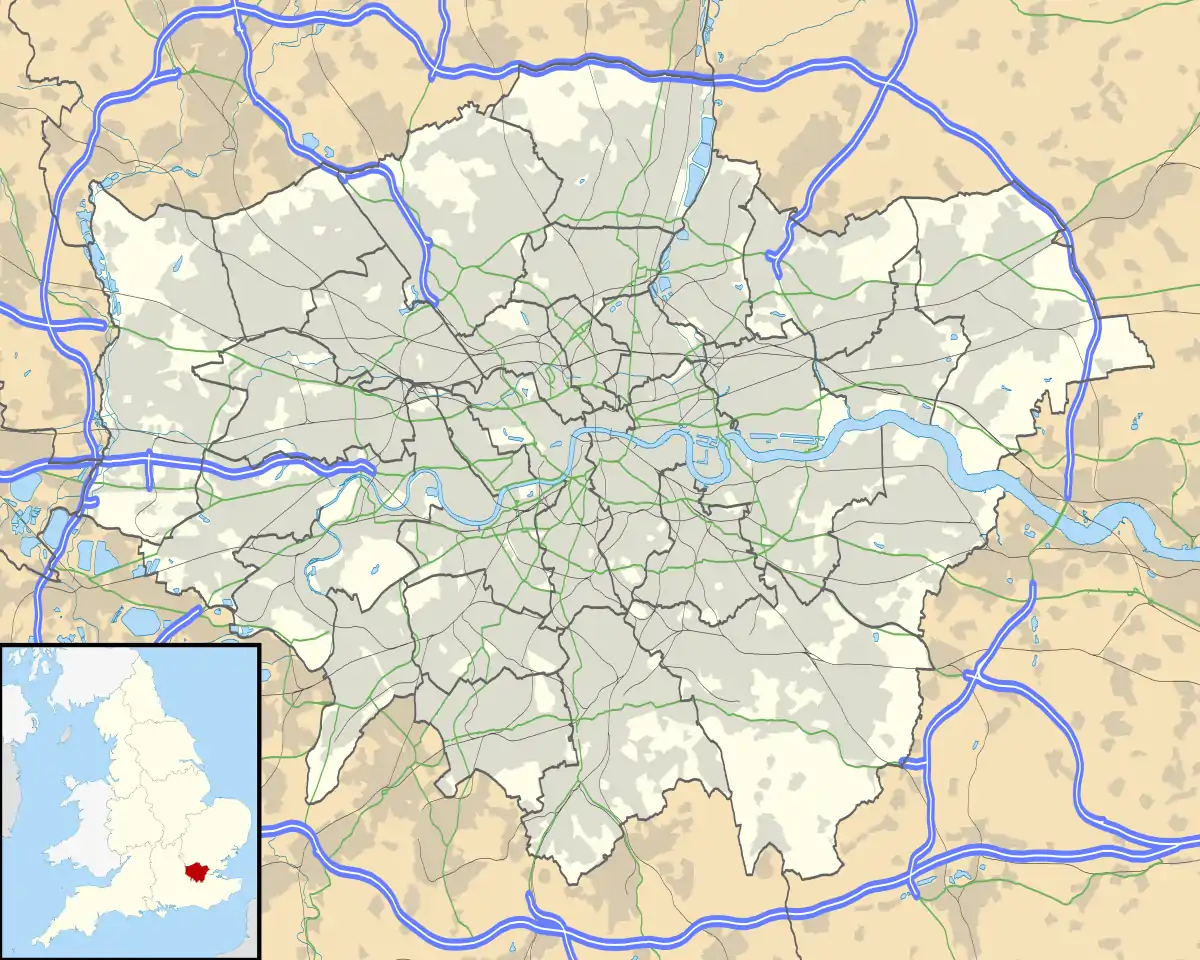

Royal Artillery Barracks Location within London | |

| Coordinates | 51°29′14″N 0°3′31″E |

| Type | Barracks |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Ministry of Defence |

| Operator | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1776–1802 |

| Built for | War Office |

| In use | 1802-present |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | 1st Battalion, The Royal Anglian Regiment National Reserve Headquarters, Royal Artillery The King's Troop, Royal Horse Artillery Countess of Wessex's String Orchestra |

History

In 1716 two permanent field companies of Artillery (each of a hundred men) were formed by royal Warrant and placed under the command of the Master-General of the Ordnance. They were initially quartered in the Warren, about half a mile from the current barracks site. By 1771 the Royal Regiment of Artillery numbered over 2,400, over a third of whom were usually quartered in Woolwich.[2] Having outgrown its barracks in the Warren, the regiment looked to establish itself in new quarters elsewhere in Woolwich.

18th-century establishment

Work on the new barracks began in 1774 on a site overlooking Woolwich Common. As originally built (1774-6) the barracks frontage was only half the present length, being the eastern half of the current south elevation, with the clock pediment and turret positioned centrally. Soldiers were accommodated in the central block, officers in the smaller blocks on either side; the blocks were linked by a pair of brick arcades with large rooms behind: a guard room to the west, an officers' mess to the east. Behind the three blocks was an open yard area and a row of kitchens, with a house for the barrack-master added beyond.

In 1793 the Royal Horse Artillery was formed, and a separate long barracks range was built for them to the north of (and parallel with) the original blocks; it was arranged (cavalry-style) with soldiers on the first floor and stables for the horses below.[2]

19th-century enlargement

By the turn of the century the size of the Regiment had grown substantially and larger barracks were needed. To begin with, in 1801, the Horse Artillery barracks was expanded to form a quadrangle by the addition of a parallel range to the north, linked to it by officers' quarters at either end. Beyond this, in what became the north-east corner of the site, a riding school was built with a farriery attached. James Wyatt was the architect for these works.

Then in 1802-5, the entire barracks was more than doubled in size by erecting something close to a facsimile alongside to the west: in this way the south front was doubled in length by the building of three new blocks (very similar to the first three, but with a wind-dial in place of the clock); and behind these blocks a second Horse Artillery quadrangle was built. Then, to the north of the each quadrangle, a larger, three-storey block was built to provide barrack accommodation for the Corps of Royal Artillery Drivers (again with stables on the ground floor and soldiers' rooms above); these barracks ran along the full length of the northern edge of the site, up as far as the riding school. The south range of the barracks, facing on to the parade ground, was for the foot artillery. Between these and the quadrangles, a number of ancillary buildings and structures were provided, including a coal store, engineers' yard, canteen, stores and office buildings, as well as the barrack-master's house.[2]

For the south front, which faced on to the parade ground, James Wyatt designed a centrepiece triumphal arch to marry the two halves of the frontage together. A companion arch was provided to the north (plainer, but of comparable size), with a central avenue running between the two; and similar arches were placed at either end of each quadrangle (providing a through-route from east to west). On the south façade, Wyatt linked each set of three blocks with colonnades (stuccoed to match the central arch): behind the first he built offices for the regiment's senior officers, behind the next was a new officers' mess ('supposed to be the largest in England',[3] and later expanded in the 1840s); behind the third was the guard room (with a library and reading room added above), and behind the last a regimental chapel. The chapel was a large galleried space, with seating for close to 1,500 (later increased to almost 1,800 with the addition of an upper gallery in 1847). When a new garrison church was built in the 1860s, the chapel within the barracks became redundant, so it was converted to become a theatre for the Royal Artillery Dramatic Society.

The barracks were for the most part completed by 1806; by then they already housed 3,210 officers and men, and 1,200 horses.[2] In 1822 the Corps of Drivers was disbanded, with field artillerymen trained to serve as drivers instead; having thus acquired horses, the Field Artillery moved into the northern range of barracks and stables, leaving the still dismounted Garrison Artillery in the south range. Numbers fluctuated somewhat in the first half of the century: the size of the garrison was reduced during the years of relative peace after Waterloo (until in 1833 the barracks contained just 1,875 men and 419 horses); but it then began growing again. In the census of 1841, a total of 2,862 people were recorded as living in the barracks, of whom 759 were women or children (there being no officially-provided housing for married soldiers at that time). In the wake of the Crimean War, with the army largely garrisoned at home, the barracks became notoriously overcrowded.

In 1851 work began (to a design by T. H. Wyatt) on a new building for the Royal Artillery Institution; it was opened three years later, standing immediately to the north of the easternmost block of the south range of the barracks.[2] The RA Institution was a scientific association, offering officers the opportunity to hear lectures on physics, chemistry, geology, artillery, military tactics and history.[4] The building included a horseshoe-shaped lecture theatre, a library, a laboratory, a museum, and facilities for drawing, sketching, printing, modelmaking and photography. An 'Advanced Course for Artillery Officers' was set up within the Institution in 1868: a two-year examined course of higher scientific study. From 1871 the Department of Artillery Studies made use of the Institution's facilities to provide instruction for all newly-commissioned Artillery officers (with accommodation being provided in the adjacent south-east block of the barracks). In 1885 the Department (together with the Advanced Course) moved to the nearby Red Barracks and was renamed Artillery College.

By the 1880s, the Field Artillery (together with their horses) had been provided with separate barracks accommodation nearby: one brigade in the Hut Barracks, another in the Grand Depot & Engineer Barracks. The Garrison Artillery remained in the south range of the Artillery Barracks (where the District Staff R.A. were also accommodated). The Horse Artillery continued to occupy the two quadrangles. One of the northernmost blocks now housed a cavalry regiment.[5] In 1893-4 a Church of England Soldiers' Institute was built in the north-east corner of the site, providing a concert hall, library and reading room, music room, games rooms and other facilities.[2]

20th-century reconstruction

The theatre (the former chapel) burned down in 1903 and was rebuilt to a design by W. G. R. Sprague;[2] and in 1926 a new Regimental Institute was built to replace the canteen (it provided among other facilities a restaurant, a ballroom a library and a billiards room). Otherwise there were relatively few structural changes during the first half of the century. In the early 1930s, the barracks still housed some 3,000 soldiers, 1,000 horses and between 80 and 200 officers; with mechanisation, the stables were converted into more rooms for soldiers. In 1939 troops were moved out of the barracks, which (along with other facilities in the Woolwich area) was vulnerable to air attack; but the following year it was filled again with evacuees from Dunkirk. Parts of the barracks were damaged during the Blitz, the easternmost block of the south front being destroyed along with the Royal Artillery Institution (which had been inserted behind it in 1851-4).

After the war, the future of the barracks was kept under discussion. Finally, in 1956, the decision was taken that the Royal Artillery would retain it as their depot, but with everything behind the south front demolished and rebuilt (with the exception of Wyatt's officers' mess, which would remain in situ). Over the next ten years twelve new three-storey barrack blocks were erected on the site. Initially, the north, west and east triumphal arches (which were all listed buildings) were retained; those to the east and west were demolished in 1965, to make way for a gym and a computer centre, and three years later the north arch was lost to road widening (a plan that it would be dismantled and re-erected coming to nothing). The retained south range blocks were reconfigured internally, and a replica of the destroyed easternmost block was built.[2] In 1973 the barracks were designated as a Grade II* listed building.[6]

On 23 November 1981, the Provisional Irish Republican Army targeted Government House of the Royal Artillery on Woolwich New Road in a bomb attack which injured two people.[7] In 1983 the barracks itself was targeted, again by the IRA, in a bombing that injured five soldiers.

21st century rebuilding and rundown

Since the nineteenth century, the appropriateness of Woolwich as a base for the Artillery had been questioned. Suggestions of a move came to nothing until a Defence Estates Review in 2003 proposed a move to Larkhill on Salisbury Plain (where the Royal School of Artillery has been based since 1915). After very nearly 300 years in Woolwich, the last Artillery regiment (the 16th) left the barracks in July 2007.[8] In 2008-11 the barracks were again largely rebuilt behind the south façade.

The place of the Artillery was taken by the public duties line infantry battalion and incremental companies of the Foot Guards (who moved in from Chelsea Barracks and Cavalry Barracks). Soon afterwards, the Second Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment was posted to Woolwich from Cyprus. In 2012, an artillery link was regained when the King's Troop, Royal Horse Artillery moved from the St John's Wood Barracks to a new headquarters on the Woolwich site, bringing with them a complement of 120 or thereabouts horses, historic gun carriages and artillery pieces used in their displays.[9] Following the departure of the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment, the First Battalion Royal Anglian Regiment moved in to the Barracks in 2014.[10]

In May 2013 drummer Lee Rigby was murdered by extremists just outside the Barracks in a terrorist attack.[11]

Closure

In November 2016 the Ministry of Defence announced that the site would close in 2028, with all army units currently stationed in Woolwich scheduled to be relocated.[12] In 2020, it was announced that Napier Lines were to be retained.[13]

However, in December 2020, Greenwich Borough Council unanimously passed a motion to oppose the sale of the barracks,[14] and a petition to save the barracks has surpassed 5,000 signatures.

Curtilage

Parade ground

In 1784, the land in front of the south range of the barracks was levelled and laid with gravel to form a parade ground. In 1862 a war memorial was 'erected by their comrades to the memory of the Officers, Non Commissioned Officers and Men of the Royal Regiment of Artillery who fell during the War with Russia in the years 1854, 1855, 1856'. Designed by John Bell, the memorial is topped by a large bronze figure of Liberty distributing wreaths from a basket.[15]

For many years the 17.75-ton Bhurtpore gun, captured by Lord Combermere after the 1826 siege of Bhurtpore, stood outside the barracks.[16][17] A set of four Florentine guns dating from the mid-18th century were likewise a fixture on the southern edge of the parade ground for many years.[18] They were all removed to Larkhill in 2007, along with other historic cannons which had stood in front of the barracks.

In 2008, for the benefit of the public duties units moving to the barracks, the central part of the parade ground was extended so as to assume the same dimensions as Horse Guards Parade.[2]

Barrack Field

Barrack Field, to the south of the Parade Ground, originally formed part of the Bowater Estate (along with the plot on which the Barracks themselves were erected). Having acquired the land, the Board of Ordnance built a ha-ha in 1778 along its southern boundary, to prevent livestock from straying on to it from the Common. By 1806 the Board had acquired ownership of the common, and the line of the ha-ha was shifted further south as a way of straightening the boundary. Since then, the Barrack Field (together with the Common) has been used for various military purposes, including artillery exercises, physical training and large-scale military parades. The Royal Artillery Cricket Club played on a cricket ground here (dating from the 18th century); and to the east there were tennis courts and football pitches at various times. During the First World War the Barrack Field was used as a mobilization camp with over 200 tents. During the Second World War part of it was turned into allotments.[19]

Gun Park

In 1803 the Board of Ordnance built a mortar battery for artillery training, immediately to the west of the parade ground. The battery was orientated to fire in a south-southeast direction, the target being a flagstaff positioned three-quarters of a mile away at the southern end of the common.[19] A pedimented building, which still stands nearby, served as an ammunition store and shifting room. As described in 1846, live-fire mortar and howitzer practice took place at the battery 'every Monday, Wednesday and Friday [from] as early as half past nine in the morning';[20] live-fire gun practice, on the other hand, continued to take place in the Royal Arsenal (on a firing range near the proof butts).[21] Use of the mortar battery ended in the 1870s, when live artillery firing was restricted to Plumstead Marshes and Shoeburyness.

Immediately north of the mortar battery the Gun Park was laid out (later known as the Upper Gun Park): it was a drill ground for field-battery exercises, around which gun-carriage sheds were built to the north and west. Firing positions for six guns were also provided, immediately to the south of the mortar battery. These were used as a saluting battery; guns were fired from here daily at 1 p.m. and at 9.30 p.m. to announce 'the time of day [...] to the garrison and neighbourhood of Woolwich'.[22] It remained in use for gun salutes for much of the 20th century and, as reported in 1970, the 'firing of the 1 o'clock gun from the Greenhill Battery' continued to take place daily.[19] Later the guns were removed and placed in front of the Royal Military Academy; but their footings remain, along with several surviving carriage sheds and other buildings, around the edge of the former drill ground (now used as a car park).[2]

Woolwich Garrison

Woolwich had extensive links with the military and with the manufacture of heavy weaponry. Key to its character was the Board of Ordnance, which acquired land here in the 17th century known as the Warren, which evolved into the Royal Arsenal (among other things the British Government's principal armaments manufacturing facility for over 200 years). The Board was a military as well as a civil office of state: the Royal Regiment of Artillery was first raised by them in the Warren in the early 18th century, and several other units were established or based there; but when the Royal Artillery left the Warren for the Common, the military centre of gravity shifted with it: soon a variety of military quarters, institutions and amenities sprang up the surrounding area, and a new garrison town began to emerge.

Over time Woolwich Garrison has been composed of some or all of the following elements, in addition to the RA Barracks:

Woolwich Common

Use of Woolwich Common by the military predated the opening of the barracks: guns had been tested there since the 1720s, and in 1770 an artillery range was set up for target practice. In 1802-4 four Acts of Parliament transferred leasehold ownership of the common (which until then had also been used as public grazing land) to the Board of Ordnance; the 'Gatehouse' on Repository Road (which originally housed soldiers guarding the garrison) dates from around this time.[23] The Board acquired freehold ownership in 1812.

The common, like the Barrack Field, has long been used for sport: on the west side of the common a stadium was built by the Army in 1920; it was used for football, rugby, show jumping, athletics, and also military tattoos.[19] The shooting events at the 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics were held at a temporary venue on the northern edge of the common;[24] (the original plan to conduct the shooting at the National Shooting Centre at Bisley, Surrey, was changed after the International Olympic Committee expressed reservations about the number of sports proposed to be staged outside London).

Royal Horse Infirmary

The common was regularly used for the training and exercise of horses (activities which have resumed since the return to Woolwich of the King's Troop RHA).[25] The Royal Artillery and the Royal Horse Artillery both made extensive use of horses, as did the Royal Army Service Corps (based in Connaught Barracks). In 1805, at the far south-western corner of the common, a Veterinary Establishment was built by the Ordnance Veterinary Service. Later named the Royal Horse Infirmary, it became the headquarters of the Army Veterinary Department (predecessor of the RAVC, whose Corps Depot remained in Woolwich until 1939). Adjoining it was a Remount Establishment, to procure and train new horses for the Artillery and Royal Engineers, which was later expanded to form the main English depot of the Army Remount Service.

Shrapnel Barracks

Alongside the Royal Horse Infirmary, a hutted camp was built at the time of the Crimean War to serve as a cavalry barracks; the 'Hut Barracks' later housed Artillery units. In 1896 Shrapnel Barracks opened on the site, to provide accommodation for the men and horses of a field brigade of Artillery.

Royal Military Academy

The Royal Military Academy, which trained officer cadets of the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers from 1741 to 1939, was initially founded in the Warren before moving into new premises built at the southern end of Woolwich Common in 1806. Expanded at various points, the institution remained here until being amalgamated into the Royal Military College, Sandhurst in 1939.

Military Hospitals

In the aftermath of the Crimean War, Woolwich gained a new military hospital named the Herbert Hospital. Opened in 1865, it was (like the nearby Royal Marine Infirmary, but on a larger scale) a 'pavilion plan' hospital: built in accordance with the latest design principles for disease prevention, as advocated by Florence Nightingale, John Roberton and Douglas Galton (who was the hospital's architect).[26] In 1972 work began on building a new hospital nearby (on the site of Shrapnel Barracks and the Veterinary Hospital) to be named the Queen Elizabeth Military Hospital; when it was opened in 1977, the Royal Herbert Hospital closed.

Royal Military Repository

In the 1770s, Captain (later Sir) William Congreve created a 'Repository of Military Machines' in the Warren: a collection of guns, mortars, models and other items used to teach gunners and engineers the history and practice of their craft. At the same time, he devised a set of practical training exercises, which were carried out under his supervision on open ground nearby; known as 'Repository Exercises', these involved manhandling heavy guns and equipment over 'Ditches, Ravines, Inclosures or Lines' designed to simulate challenges likely to be encountered in the field. In 1778 the Royal Military Repository was given formal recognition, and Repository Exercises became compulsory.[2]

In 1802 the building in the Warren burned down; but shortly afterwards Congreve re-established the Repository on recently-acquired land just to the west of the Barrack Field. There, what became known as the 'Repository Grounds' were laid out with trees, ditches, ravines, earthworks, and other structures in order to train troops in the movement of guns, ammunition and heavy equipment across difficult terrain. There were two large ponds, on which men were taught 'to lay pontoons, to transport artillery upon rafts, and all the different methods that can be adopted for the passage of troops across rivers, &c.'.[3] In the 1820s an earthwork training fortification was added along the length of the eastern boundary, on which were mounted 'all the different sorts of cannon used in the defence of fortified towns'.[3]

On the southern part of the site, four long gun-carriage sheds were built in 1802-5 (the northernmost, with offices at either end, designed to accommodate items from the Repository's historic collection). To the north of the sheds, the Rotunda (previously erected at Carlton House to celebrate the peace of 1814) was rebuilt in 1820; it served to house the surviving model collection of the Royal Military Repository (which in the meantime had been on display in the old Academy in the Warren).[2]

In the 1880s it was still the case that all officers of the Artillery (including those of the Militia and Volunteers) had to pass a term of instruction at the Repository.[27] The Rotunda by this time had been opened to the public as the Royal Artillery Museum. In 1890, the Royal Military Repository closed (much of its work having transferred to Shoeburyness). The Repository Woods remained in used for military training, however, through the 20th and into the 21st century.[2]

Napier Lines

In the early 20th century the Ordnance College converted some of the old Repository Sheds into training workshops, accommodating 520 'wheelers, fitters, smiths, painters and others'. By the time of the Second World War it had evolved into a vehicle maintenance base, and after the war it was taken over by the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME), whose senior officer on site was accommodated in 'Repository House' (the former Gatehouse on Repository Road). In 1995 (REME having moved to new facilities in the main barracks) the workshops were replaced with large new sheds to store the vehicles and matériel of the 16th Air Defence Regiment; they were named Napier Lines (the regiment having just relocated from Napier Barracks, Dortmund, in Germany).[2] 16th Regiment, the last Regiment of Royal Artillery to be stationed in Woolwich, departed in 2007. In 2011 part of the area was converted, with new stable blocks added, to form a base for the King's Troop Royal Horse Artillery named George VI Lines.

The Observatory (Magnetic Office)

On Green Hill, east of the Repository, an observatory was built in 1838. This was the first headquarters of the Royal Artillery Institution (a scientific educational club for officers), which had been founded that year by Lieutenants John Lefroy and Frederick Eardley-Wilmot. From 1839 it also served as the home base for Edward Sabine's global survey of terrestrial magnetism (with which Lefroy and Eardley-Wilmot were closely involved); it was known for a time as the Magnetic Office, until the Magnetic Survey moved to Kew Observatory in 1871.[28] The observatory was extended in 1853, with the addition of a domed equatorial room. The following year, the RA Institution moved into new larger premises within the main Barracks complex; but it continued to use the observatory for astronomy until 1926. While the equatorial room was demolished soon afterwards, the original small transit room survives, alongside the pedimented annexe which originally housed the Institution's library and reading room. In the 21st century it accommodated the Royal Military Police.[2]

Housing and other amenities

In the area between the Gun Park and the Rotunda, terraced housing was built in the 1920s to serve as married quarters for soldiers. More terraces were added in the 1930s and 1950s; as Green Hill Barracks they continued to house soldiers into the 21st century. North of the Gun Park, rows of gun carriage sheds were built in the 19th century; known as Congreve Lines, the area now contains the Army Medical Centre and welfare services. Further to the north, a Regimental School had been established in 1808, in timber sheds by the barracks. In the 1850s the school was rebuilt on what is now Green Hill Terrace. By the 1860s, Green Hill Schools had a daily attendance of over a thousand children, with teaching also provided on site for non-commissioned officers as a way of combatting illiteracy. In the evening the building was put to social and other uses; it remained in military use until the 1960s.

St George's Garrison Church

St George's Garrison Church was built to the east of the parade ground in 1863 (replacing the chapel within the barracks). Romanesque in style with Byzantine detailing, it was largely destroyed by a V1 flying bomb on 14 July 1944, but the ruins have been preserved as a memorial.

Royal Artillery Hospital (Connaught Barracks)

In 1780, shortly after the opening of the artillery barracks, the Royal Artillery Hospital was opened close by, just to the east of the barracks. Later known as the Royal Ordnance Hospital, it was one of the first purpose-built military hospitals in England. Over time the building was expanded: first in 1794-6 (when two new wings were added, one for a convalescent barracks, the other for surgeons' quarters) and then in 1804-6, when a new hospital complex was added to the north (linked by a long covered gallery to the old buildings, which continued to provide convalescent space and staff accommodation).

Another ward block was added to the east in 1854; but after the establishment of the new Herbert Hospital in 1865, the Artillery Hospital buildings were converted into barracks and went on to serve as headquarters of the Military Train (who were the main providers of land-transport capability for the Army). The officers were accommodated in the 18th-century buildings, and the men in the 19th-century ward blocks. Stables for 240 horses were built in the former hospital grounds to the east (previously left undeveloped to prevent spread of diseases). Under the name Connaught Barracks, the complex went on to be the base of the Military Train's successor, the Horse Transport Branch of the Army Service Corps. Following mechanisation, the stables were renamed 'Motor Transport Lines', reflecting the Corps' new mode of conveyance.[2] The Royal Army Service Corps remained here until 1962, when the Corps was amalgamated and the site redeveloped (the eighteenth-century hospital buildings survive as Connaught Mews, an apartment complex off Grand Depot Road).[29]

The Grand Depot

In 1781 a garden was laid out to the north of the RA Hospital, initially to serve as a kitchen garden for the adjacent Royal Artillery Barracks. In 1804 the Grand Depôt of Field Artillery was established here: four long low sheds were built on the site, flanking a central range of workshops and offices, with a pair of magazines alongside to the west (all to designs by Lewis Wyatt). Here were maintained at all times 'thirty Brigades of Field Artillery, with Ammunition and Stores complete, and in a perfect state of readiness for any service' (a 'Brigade' in this context being defined as 'five Guns and one Howitzer').[30] The Grand Depôt served as headquarters for the Ordnance Field Train, a forerunner of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, which was responsible for the custody, conveyance and distribution of guns, ammunition and stores to Artillery units on active service (and of ammunition to the Army as a whole). In 1859 the Field Train was amalgamated into the Military Store Department of the War Office.

In 1856, a Royal Army Clothing Department factory was built on the site of the two magazines (it also covered over most of what remained of the garden). Twelve years later, the factory moved to Pimlico.[27]

On 1 October 1871, the entire area (then known as the Grand Depot Stores) was handed over to the Commandant of Woolwich Garrison and converted into additional barracks for the Artillery: Grand Depot Barracks.[31] The former clothing factory became the main block of the barracks, and the old Grand Depôt sheds were converted into stables (with one of them being demolished to make space for a sizeable drill yard).[27] By the 1880s Grand Depot Barracks accommodated a full field-brigade of artillery; and in the 20th century it continued to function as an extension of the adjacent Royal Artillery Barracks. The surviving Grand Depot buildings (including the listed central block of 1805) were demolished in 1970.

Artificers Barracks

In 1803 a barracks was built further to the east (south of Love Lane, west of Thomas Street), to designs by James Wyatt, to serve as headquarters for the Corps of Royal Military Artificers (later renamed the Royal Sappers and Miners) who, like the Royal Artillery, were under the Board of Ordnance rather than the War Office. By the 1840s it had been expanded to house three Companies (273 men in total). In 1856, however, the Sappers and Miners were amalgamated into the Royal Engineers, for whom a new Corps headquarters was established in Chatham. Nevertheless, a small detachment of Engineers remained to see to the needs of the garrison, and through the 20th century the barracks were referred to as the Engineer Barracks.

After 1856 the barracks accommodated the cadets of the Practical Class of the Royal Military Academy, until 1863 when they moved back to the (newly-extended) main RMA buildings. Afterwards, spare capacity in the Engineer Barracks was used by the Royal Artillery as overflow accommodation for the Grand Depot Barracks next door. Again, despite being listed the Engineer Barracks were demolished, in 1970.[2]

Housing and other amenities

From 1824, the Commanding Royal Engineer (CRE) Woolwich lived in Mill Lane House (having moved there from premises in the Arsenal). When the Corps headquarters moved to Chatham, an office building (Engineer House) was built nearby as a base for the Engineer detachment remaining in Woolwich. It contained a drawing office and a darkroom, and a range of workshops was built alongside.

South of Engineer House, facing the Barrack Field, was the Garrison Dispensary: a single-storey range of buildings which later functioned as an Auxiliary Hospital;[2] in the later 20th century it was known as the Garrison Medical Centre.[32] Behind it stood the Garrison Female Hospital (later renamed the Military Maternity Hospital), which had been built at the same time as the Herbert Hospital to designs by the same architect (Douglas Galton). It remained operational until the mid-1970s.[32]

South of the Dispensary stood St George's House (the Royal Artillery chaplain's quarters), and Government House (until 1936 the residence of the Garrison Commandant, which continued to serve as the Garrison Headquarters into the 1980s).[2] On land further back, towards Brookhill Road, several long ranges of married quarters housing were built in the late 19th century; these were replaced by new army houses in the 1970s. Older rows of married quarters, dating from the 1860s and known as Cambridge Cottages, stood further to the north.

Military use of the former Naval Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard had been one of England's principal Royal Dockyards during the Tudor and Stuart periods, but it closed in 1869 as the Thames was by then too difficult to navigate for the naval vessels of the time. Subsequently, most of the site served as a subsidiary Ordnance Depot for the Military Store Department based in the Arsenal.[33] Later an Army Pay Office was established here, responsible for the accounts not only of the Royal Field Artillery and Royal Horse Artillery, but also those of all soldiers serving with the Army Service Corps, the Army Ordnance Corps, the Army Veterinary Corps, and the Army Pay Corps itself. By 1914 it had grown to be the largest Army Pay Office in the country, with a military staff of 90 responsible for the administration of 60,000 personal accounts.[34] The Records Offices of the Army Service Corps and Army Ordnance Corps were also based in the former Dockyard.

Military use of the former Marine Barracks

The closure of the Dockyard had also led to the Royal Marines vacating their barracks and infirmary on nearby Frances Street. The barracks were renamed Cambridge Barracks, and subsequently housed regiments of infantry; rows of married quarters ('Cardwell Cottages') were built to the north-east in 1872. After closure, the barracks were almost entirely demolished in 1972.[35] The former infirmary was renamed Red Barracks and went on to serve as the headquarters for what became the Royal Army Ordnance Corps until 1921. From 1885, Artillery College was also based there; it later expanded and was renamed the Military College of Science, before moving out at the start of the Second World War. Later housing the Royal Artillery Records Office and other functions, Red Barracks was demolished in 1975; only the perimeter wall remains.[36] On the northwest corner of Frances Street and Hillreach, opposite the barracks security gate, is the Kings Arms pub, targeted by the IRA in November 1974 in a bombing which killed Royal Artillery Gunner Richard Dunne and another man, and injured 35 others.[37]

See also

- Royal School of Artillery

- Wentworth Woodhouse, another building with a long facade

References

- Jones & Woodward, The Architecture of London, 1983 ff

- The Survey of London: Woolwich (2012)

- London Encyclopaedia; Or, Universal Dictionary of Science, Art, Literature and Practical Mechanics (Volume 22). London: Thomas Tegg. 1829. pp. 666–667.

- "The Military Institutions and Boards of Examination of England". Colburn's United Service Magazine: 486–502. August 1872.

- Atkins, T. (1883). Army & Navy Calendar. London: W. H. Allen. p. 158.

- Historic England. "Royal Artillery Barracks Main Building (1078918)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/written-answers/1996/mar/04/terrorist-incidents

- "End of an era for historic barracks". News Shopper. 6 August 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- King's Troop moves to its 'spiritual home' in Woolwich at BBC News, 7 February 2012. Accessed 8 February 2012

- "Regular Army Basing Plan 5 Mar 13" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Woolwich attack: murdered soldier Drummer Lee Rigby 'would do anything for anybody’ - Telegraph

- "A Better Defence Estate" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "MOD Confirms Changes To Base Closure Plans". Forces News. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- "Greenwich Council opposes MOD sale of Woolwich Barracks". News Shopper. 1 December 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- "Memorial: Royal Artillery - Crimean War". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- "Obituary: Viscount Combermere". The Daily Telegraph. 16 November 2000. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Murray, John (1878). Handbook for England and Wales: Alphabetically Arranged for the Use of Travellers ... J. Murray. p. 486.

- Lefroy, Brig.-Gen. J. H. (1864). Official Catalogue of the Museum of Artillery in the Rotunda, Woolwich. London: HMSO. pp. 26–27.

- Newsome, Sarah; Williams, Andrew. "Woolwich Common, Woolwich, Greater London: An Archaeological Survey of Woolwich Common and Its Environs". Historic England. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- The Pictorial Guide to Woolwich. London: Wm S. Orr & Co. 1846. p. 18.

- James, Charles (1811). The Regimental Companion (7th ed.). London: T. Egerton. p. 80.

- "A Sparrow's Nest in a Gun-Carriage". The Family Friend: 161. 1885.

- "Woolwich Common Conservation Area Appraisal". Royal Borough of Greenwich. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- London2012.com profile of the venue. Archived 5 September 2012 at Archive.today - accessed 10 May 2012.

- Video: Royal Horse Artillery training on Woolwich Common, 30 March 2017.

- Cook, G. C. (June 2002). "Henry Currey FRIBA (1820–1900): leading Victorian hospital architect, and early exponent of the "pavilion principle"". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 78 (920): 352–9. doi:10.1136/pmj.78.920.352. PMC 1742402. PMID 12151691.

- Vincent, William Thomas (1885). Woolwich: Guide to the Royal Arsenal &c. London: Simpkin, Marshall & co. p. 55. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Duncan, Francis (1873). History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Volume 2. London: J. Murray. pp. 465–469.

- "Connaught Mews History".

- XVIIth Report of the Commissioners of Military Enquiry. London: Parliament (House of Lords). 1812. pp. 203–212.

- "First or Woolwich Dockyard Division". Reports from Commissioners. 30 (17): 70. 1872.

- "Royal Herbert Hospital". QARANC - Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "The Royal Dockyards of Deptford and Woolwich". Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "The Army Pay Services on the Eve of the Great War". Royal Army Pay Corps Regimental Association. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Bedford, Kristina (2014). Woolwich Through Time. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445615998.

- The Survey of London: Woolwich (2012)

- "History repeating itself: Same barracks were targeted by IRA bombers nearly 40 years ago". Express. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

External links

- Location map - aerial photo also available

- History of the Royal Artillery Theatre

Census Returns

- 1891 UK Census class:RG12. piece:534. folio=66. p. 1. - Woolwich Arsenal Grand Depot Barracks & Cambridge Cottages

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Artillery Barracks. |