Rumwold of Buckingham

Rumwold was a medieval infant saint in England, said to have lived for three days in 662.[2] He is said to have been full of Christian piety despite his young age, and able to speak from the moment of his birth, professing his faith, requesting baptism, and delivering a sermon prior to his early death. Several churches were dedicated to him, of which at least four survive.

Saint Rumwold (or Rumbold) | |

|---|---|

St Rumbold's Well in Buckingham | |

| Saint, Prince | |

| Born | 662 AD Walton Grounds near King's Sutton, Northamptonshire |

| Died | 662 AD (aged 3 days) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Western Orthodoxy |

| Feast | 3 November[1] 28 August (translation of relics) |

Name

His name has a number of alternative spellings: Rumwald, Runwald, Rumbald, Rumbold, Romwold, Rombout. Rumbold is the more common name used today, with streets in Buckingham and Lincoln being spelt this way.

Hagiography

According to the 11th century hagiography, Vita Sancti Rumwoldi, he was the grandson of Penda of Mercia (a pagan, and the son of a king of Northumbria. His parents are not actually named; Alhfrith, son of Oswiu of Northumbria, did marry a daughter of Penda, Cyneburh, but Alhfrith was never king of Northumbria himself, although his father was (Alhfrith did rule the subkingdom of Deira for a time). There have, however, been doubts about whether these were his parents: for instance, the Northumbrian king is described as a pagan, but Alhfrith was a Christian (at least according to Bede, who says Alhfrith convinced Penda's son Peada to convert to Christianity). Although it has been stated that Cyneburh is not known to have had any children, Northumbrian genealogy states she and Alhfrith had a further son, Osric, who subsequently became King of Northumbria himself (source: Stenton).

In the Vita, Rumwold's mother is described as a pious Christian who, when married to a pagan king, tells him that she will not consummate the marriage until he converts to Christianity; he does so, and she becomes pregnant. The two are called by Penda to come to him when the time of her birth is near, but she gives birth during the journey, and immediately after being born the infant is said to have cried out: "Christianus sum, christianus sum, christianus sum" ("I am a Christian, I am a Christian, I am a Christian"). He went on to further profess his faith, to request baptism, and to ask to be named "Rumwold", afterwards giving a sermon. He predicted his own death, and said where he wanted his body to be laid to rest, in Buckingham.

Rumwold is reported to have been born in Walton Grounds, near King's Sutton in Northamptonshire, which was at that time part of the Mercian royal estates, possessing a court house and other instruments of government. The field in which he was born, where a chapel once stood on the supposed spot, may still be seen. King's Sutton parish church claims that its Saxon or Norman font may well have been the one where Rumwold was baptised. Rumwold was baptized by Bishop Widerin.[3]

There are two wells associated with his name: in Astrop, just outside Kings' Sutton, and at Brackley and Buckingham, where his relics once lay.[4] Church dedications largely follow the missionary activity of Saint Wilfrid, who was the personal chaplain of King Alhfrith (source: Bede), but once spread as far as North Yorkshire, Lincoln, Essex and Dorset.

Boxley Abbey in Kent had a famous portrait of the saint. It was small and of a weight so small a child could lift it but at times became so heavy even strong people could not lift it. According to tradition, only those could lift it who had never sinned.[5] Upon the Dissolution of the Monasteries in England, it was discovered that the portrait was held by a wooden pin by an unseen person behind the portrait.[6]

In 2000, a complete Orthodox Christian service to Saint Rumwold was written along with a tone system (Orthodox musical system) with which to sing it which also has more general application. The service is performed on his two feast days, which are 3 November (main feast) and 28 August (translation of relics). In 2005, the former church of Saint Rumwold in Lincoln, which is now a college, erected a plaque to celebrate the connection.

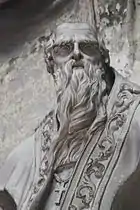

Hanswijk Basilica, Mechelen

St. Rumbold of Mechelen

There has been some historical confounding between Rumwold of Buckingham and Rumbold of Mechelen. The latter is locally known by the Latin name Rumoldus and in particular his name in Dutch, Rombout (in French spelled as Rombaut), and assumedly never called Rumwold. His usual names in English are Rumold, Rumbold, Rombout, and Rombaut. A compilation about three saints' lives as translated by Rosalind Love shows that an unknown author "corrected" a 15th-century attribution as "martyr" (assumedly Rumbold, who was murdered in Mechelen) by annotating "confessor" (fitting Rumwold, who was no martyr), and that the original dedication of churches in Northern England appears uncertain, be it that "There is little sign that St Rombout was venerated in Anglo-Saxon England. Certainly his feast is not mentioned in any surviving pre-[C]onquest calendar".[7]

References

- Love, Rosalind C. (1996). "4. St Rumwold of Buckingham and Vita Sancti Rvmwoldi — (ii) The Liturgical Evidence". Three Eleventh-Century Anglo-Latin Saint's Lives — Vita S. Birini, Vita et Miracula S. Kenelmi, Vita S. Rumwoldi. p. cxl-cxli. ISBN 0-19-820524-4. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Rumbold Leigh In Search Of Saint Rumbold (2000). Sveti Ivan Rilski Press

- Butler, Alban. “Saint Rumwald, Confessor”. Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. CatholicSaints.Info. 2 November 2013

- Douglas J. Elliott Buckingham: the loyal and ancient borough (1975). Philimore

- Wasyliw, Patricia Healy. Martyrdom, Murder, and Magic: Child Saints and Their Cults in Medieval Europe, Peter Lang, 2008, p. 71ISBN 9780820427645

- Sidney Heath (1912). Pilgrim Life in the Middle Ages. T.F. Unwin. pp. 232–233.

rood of grace.

- Love, Rosalind C. (1996). excerpts about 'St. Rombaut' (Rombout). Three Eleventh-Century Anglo-Latin Saint's Lives — Vita S. Birini, Vita et Miracula S. Kenelmi, Vita S. Rumwoldi. p. cxliii–cxliv, cli & cliv, clii. ISBN 0-19-820524-4. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

Sources

General:

- Love, Rosalind C. (1996). Three Eleventh-Century Anglo-Latin Saint's Lives — Vita S. Birini, Vita et Miracula S. Kenelmi, Vita S. Rumwoldi. ISBN 0-19-820524-4. Retrieved 26 July 2011. From which are relevant:

- Love, Rosalind C. (1996). Eleventh-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography and the Rise of the Legendary. p. xi-xxxix. See above. ISBN 9780198205241. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Love, Rosalind C. (1996). 4. St Rumwold of Buckingham and Vita Sancti Rvmwoldi. p. cxl-clxxxix. See above. ISBN 9780198205241. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Vita Sancti Rvmwoldi. pp. 91–118 (not online by Google books). See above.

- F. The Baptism of St Rumwold. p. 135-end (not online by Google books). See above.