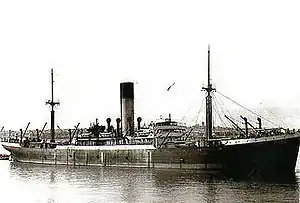

SS Automedon

SS Automedon was a Blue Funnel Line refrigerated cargo steamship. She was launched in 1921 on the River Tyne as one of a class of 11 ships to replace many of Blue Funnel's losses in the First World War.

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Automedon |

| Namesake: | Automedon |

| Owner: | Ocean Steamship Co Ltd |

| Operator: | Alfred Holt & Co |

| Port of registry: | Liverpool |

| Builder: | Palmers Sb and Iron Co, Jarrow |

| Yard number: | 920 |

| Launched: | 4 December 1921 |

| Completed: | March 1922 |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | scuttled 11 November 1940 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | refrigerated cargo ship |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: | 459.4 ft (140.0 m) |

| Beam: | 58.4 ft (17.8 m) |

| Draught: | 26 ft 2 in (7.98 m) |

| Depth: | 32.6 ft (9.9 m) |

| Decks: | 2 |

| Installed power: | 6,000 SHP |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 14.5 knots (27 km/h) |

| Capacity: | 111,000 cubic feet (3,143 m3) |

| Sensors and processing systems: | from 1934: wireless direction finding |

| Notes: | One of a class of 11 sister ships |

A German merchant raider captured and scuttled Automedon in 1940 in the Indian Ocean. Her capture is notable because she was carrying top secret documents addressed to the British Far East Command. Their capture may have influenced Japan's decision to enter the Second World War.

Automedon was Achilles' charioteer in Homer's Iliad. This was the first of three Blue Funnel Line ships to be named after him. The second was a motor ship launched in 1949 and scrapped in 1972.[1] The third was a motor ship launched in 1948 as Cyclops, renamed Automedon in 1975 and scrapped in 1977.[2]

A new class of Blue Funnel Line ships

Blue Funnel Line lost 16 ships in the First World War. Thereafter the company replaced its fleet, mainly with a class of 11 new steamships of about 460 ft (140 m) registered length, 58 ft (18 m) beam and tonnage of about 7,500 GRT, all launched between 1920 and 1923.[3]

Blue Funnel ordered members of the new class from five different shipyards. Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company built two: Automedon at Jarrow and Meriones at Hebburn, both launched in 1921.[4][5]

Palmers launched Automedon on 4 December 1921 and completed her in March 1922. Like most members of the class she was powered by two steam turbines, which drove a single screw via double reduction gearing. Between them her turbines developed 6,000 SHP and gave her a speed of 14.5 knots (27 km/h).[4] Her holds had refrigerated space for 111,000 cubic feet (3,143 m3) of cargo.[6]

In 1934 Automedon's code letters KNQG[7] were superseded by the call sign GBZR, and she was fitted with wireless direction finding.[8]

Second World War service

In the Second World War Automedon mostly sailed unescorted. When the war began in September 1939 she was en route from Britain to Australia via the Suez Canal and Colombo. She returned by the same route, reaching Liverpool on 3 March 1940.[9]

On 31 March 1940 Automedon left Liverpool for Australia, but this time sailed via Freetown in Sierra Leone and Durban in South Africa. She returned by the same route, reaching Liverpool on 21 August.[9]

Final voyage and loss

On 25 September 1940 Automedon left Liverpool for the Far East. She sailed with Convoy SL 42, which took her as far as Freetown. She then sailed unescorted to Durban, where she was in port from 25 to 29 October.[9] Her cargo included crated aircraft, motor cars, spare parts, liquor, cigarettes, bagged mail, and food including frozen meat, bound for Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai.

At about 0700 hrs on 11 November 1940, the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis intercepted Automedon about 250 nautical miles (460 km) northwest of Sumatra, approaching on a heading that would bring the two ships close together. At 0820 hrs when Automedon was less than 5,000 metres (16,000 ft) away, Atlantis raised her German ensign and uncovered her guns. Automedon at once responded by transmitting a distress signal, but managed to send only "RRR – Automedon – 0416N" ("RRR" meant "under attack by armed raider") before Atlantis jammed her transmission.[10]

Atlantis then opened fire from a range of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), four salvos hitting Automedon amidships. The first shells destroyed Automedon's bridge, killing everyone present except her helmsman, Stan Hugill. Her Master, William Brown Ewan, was on the bridge and was among those killed. Automedon was still steaming full ahead and a crewman tried to reach the DEMS gun on her stern to return fire. Atlantis fired a final salvo which hit the ship, killing the would-be gunner and stopping Automedon.

Automedon's chief officer met Atlantis' boarding party when they came aboard. Ulrich Mohr of Atlantis later said Automedon was in the worst condition he had ever seen; the close-range shelling had destroyed virtually every structure above the hull, and nothing was left undamaged. Six crew members had been killed and 12 wounded. Six of the wounded were at once transferred to Atlantis for medical treatment.[10]

A thorough search of Automedon found 15 bags of top secret mail for the British Far East Command, including a large quantity of decoding tables, Fleet orders, gunnery instructions, and Naval Intelligence reports. The most significant find was a small green bag found in the chart room near the bridge. Marked "Highly Confidential" and equipped with holes to help it to sink if it had to be thrown overboard, the bag contained an envelope addressed to Robert Brooke Popham, Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command. The envelope contained documents prepared by the British War Cabinet's Planning Division which included their evaluations of the strength and status of British land and naval forces in the Far East, a detailed report on Singapore's defences, and information on the roles to be played by Australian and New Zealand forces in the Far East in the event that Japan entered the war on the Axis side.

Captain Bernhard Rogge of Atlantis set a time limit of three hours in which 31 British and 56 Chinese crewmen, three passengers, their possessions, all the frozen meat and food and the ship's papers and bags of mail were transferred. He was concerned as another ship observing the two stationary vessels would quickly guess what was happening and send a radio message before Atlantis could take any action. Automedon was judged too badly damaged to tow, so at 1507 hrs she was sunk by scuttling charges. Her survivors eventually reached Bordeaux aboard the captured Norwegian tanker Storstad.

Captain Rogge realised the importance of the intelligence material he had captured from Automedon and quickly transferred the documents to the ship Ole Jacob, captured earlier, ordering KKpt Paul Kamenz and six of his crew to take charge of the ship and take the captured material to the German representatives in Japan.[11]

On 4 December 1940 Ole Jacob reached Kobe, Japan. The mail reached the German embassy in Tokyo on 5 December, and was then hand-carried to Berlin via the Trans-Siberian railway. A copy was given to the Japanese Government, and some argue that it influenced the Japanese decision to start what it called the "Greater East Asia War".[12] After Japan's entry into the war and the fall of Singapore, Captain Rogge was awarded an ornate katana on 27 April 1943. Japan only ever presented three such swords to foreigners, the others being to Hermann Göring and Erwin Rommel.[13]

References

- "Automedon". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "Cyclops". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Le Fleming 1961, pp. 24, 48, 49.

- "Automedon". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "Meriones". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "List of Vessels Fitted with Refrigerating Appliances". Lloyd's Register (PDF). I. London: Lloyd's Register. 1930. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). II. London: Lloyd's Register. 1933. Retrieved 29 December 2020 – via Plimsoll Ship Data.

- "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). II. London: Lloyd's Register. 1934. Retrieved 29 December 2020 – via Plimsoll Ship Data.

- Hague, Arnold. "Ship Movements". Port Arrivals / Departures. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Duffy 2005, pp. 22–24.

- Slavic 2003, p. 113.

- Arnold 2011, pp. 79–92.

- Slavic 2003, p. 237.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Michael (2011). Sacrifice of Singapore: Churchill's Biggest Blunder. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 79–92. ISBN 9789814435437.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duffy, James P (2005). Hitler's Secret Pirate Fleet: The Deadliest Ships of World War II. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6652-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Fleming, HM (1961). Ships of the Blue Funnel Line. Southampton: Adlard Coles Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seki, Eiji (2006). Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940 (cloth). London: Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-905246-28-1.

[reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007] – previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Slavic, Joseph P (2003). The Cruise of the German Raider Atlantis. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 111. ISBN 1-55750-537-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External link

- Cortazzi, Hugh (7 January 2007). "How one merchant ship doomed a colony". The Japan Times.