SS Southern Cross (1886)

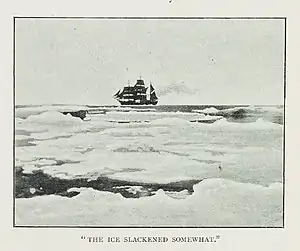

SS Southern Cross was a steam-powered sealing vessel that operated primarily in Norway and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Southern Cross in the Derwent River, Tasmania, 1898 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Owner: |

|

| Builder: |

Designed by Colin Archer, Larvik, Norway built by Ole Martin Olsen, Arendal, Norway |

| Launched: | September 1886 |

| Fate: | Lost at sea 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 520 GRT |

| Length: | 146 ft (45 m) |

| Sail plan: | barque |

She was lost at sea returning from the seal hunt on March 31, 1914, killing all 174 men aboard in the same storm that killed 78 crewmen from the SS Newfoundland, a collective tragedy that became known as the "1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster".[1]

Background

The vessel was commissioned as the whaler Pollux at Arendal, Norway in 1886, was barque-rigged, registered 520 tons gross, and was 146 feet (45 m) long overall.[2]

Pollux was designed by Colin Archer, the renowned Norwegian shipbuilder.[2] Archer had designed and built Nansen's ship Fram, which in 1896 had returned unscathed from its long drift in the northern polar ocean during Nansen's "Farthest North" expedition, 1893–96.[3]

Pollux was sold to the Norwegian explorer Carsten Borchgrevink in 1897 and renamed Southern Cross,[4][5] for the Southern Cross Expedition.

Like several of the historic polar ships her post-expedition life was short;[6] Southern Cross was sold in 1901 to Murray & Crawford, Glasgow, and took up seal hunting from Newfoundland. Southern Cross participated in every seal hunt from 1901 to 1914. In April 1914 was lost with all hands in a storm off the Newfoundland coast.[7]

Southern Cross Expedition

For the Southern Cross Expeditions, Carsten Borchgrevink purchased the steam whaler Pollux and renamed her Southern Cross. She was taken to Colin Archer's yard in Larvik and fitted out for the expedition. Engines were designed to Borchgrevink's specification, and fitted before the ship left Norway.[2]

On December 19, 1898 Southern Cross made its first Antarctic expedition where it made marine history by breaking through the Great Ice barrier to the unexplored Ross Sea.

Although Markham cast doubts on her seaworthiness (perhaps to thwart Borchgrevink's departure),[8] the ship fulfilled all that was required of her in Antarctic waters.

1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster

The 1914 sealing fleet included both Southern Cross and SS Newfoundland (under Captain Westbury Kean). In addition to minor crew changes from 1913, the fateful decision to remove the wireless set and operator from Newfoundland was taken in order to cut costs.

The fleet left St. John's on March 13, 1914. Newfoundland lost 78 sealers from her crew when they were stranded on the ice for two nights. Just as the terrible news of the Newfoundland tragedy was reaching St. John's, Southern Cross fell out of normal communication. The people of Newfoundland remained hopeful that tragedy would not strike twice, as evidenced by the April 3 newspaper article below:

Nothing has been heard of the Southern Cross since she was reported off Cape Pine on Tuesday last, and the general opinion is that she was driven far off to sea. Various reports were afloat in the city last night, one in particular that she had passed Cape Race yesterday afternoon, but upon making enquiries this and the other reports were unfortunately found to be untrue. At 5:30 yesterday the Anglo [Anglo-American Telegraph Co.] got in touch with Cape Race and learned that she had not passed the Cape neither was she at Trepassey. A message from Captain Connors of the Portia said she was not St. Mary's Bay. A wireless message was sent by the government to the U.S. Patrol steamer Senaca, which is in the vicinity of Cape Race, asking her to search for the Cross. The S.S. Kyle will also leave tonight to make a diligent search for her and it is hoped that something will soon be heard from the overdue ship, as anxiety for her safety is increasing hourly. If she had been driven off to sea, which is the general opinion expressed by experienced seamen, it would take her some days to make land again. The ship is heavily laden and cannot steam at great speed.

— The Evening Telegram April 3, 1914

Unlike the tragedy of Newfoundland's crew, the disappearance of Southern Cross remained largely unexplained as no crewmen or record of the voyage survived. While a marine court of inquiry determined that the ship sank in a blizzard on March 31, little evidence exists to verify this. Oral tradition suggests that rotten boards gave out in the heavy sea and allowed the cargo to shift and capsize the steamer. Though the wreck of Southern Cross accounted for the greater human loss of the two shipwrecks, some historians argue that the emotional impact of the Newfoundland disaster was more intensely felt because of the horrific stories survivors were able to recount.

These two disasters together constitute what is referred to as the 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster. A total loss of 251 lives from a country with a population of approximately 250,000 devastated families and communities. In his autobiographical book, Rockwell Kent describes the impact of the loss on Brigus, where many of the sealers from Southern Cross had lived. "It will pretty well clear out this place," said one resident of the ship's loss. According to Kent "The dread of the loss of this steamer had passed almost to certainty and the mention of the house, the wife, the children, the hopes and ambitions of any of those on her became a tragedy."

Legislative Response

In 1914–15, the government held a commission of inquiry to examine Newfoundland and Southern Cross sealing disasters. The commission's findings made it clear that sealers faced extraordinarily dangerous working conditions on the ice.

While legislation concerning the sealing industry had existed as early as 1873, most regulations concerned maintaining seal stock. In 1898 legislation put a limit on the number of men on each steamer, and one year later in 1899, some wage protection was instated for sealers. Arguably as a result of the 1914 Sealing Disaster and subsequent inquiries, further legislation was put in place in 1916, aimed directly at improving the safety standards and well-being of sealers. The new measures prohibited men from working in the dark; prohibited captains from ordering their crewmen to travel so far as to not be able to return to the ship within the day, and provided for rocket signals, search parties, masters' and mates' certificates, medical officers, thermometers, barometers, and better food and compensation.

In response to speculation that Southern Cross sank because of overloading, the government prohibited any ship from returning from a hunt with more than 35,000 pelts, and the Minister of Fisheries began to mark "load lines" on sealing vessels. Any ship that returned to port with its "load line" below the water would be heavily fined.

Public response

Public sympathy was very evident after the 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster. By April 27, 1914, a disaster fund set up to aid survivors and their families amounted to $88,550. It's notable that this was not limited to the sealing disasters; it was common practice in society at the time to respond to industrial accidents in this way.

In popular culture

The vessel was the subject of the book Death on the Ice by Cassie Brown,[9] and a 1991 National Film Board of Canada documentary I Just Didn't Want to Die: The 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster.[10]

To mark the 100th anniversary of the Newfoundland sealing disaster, an animated short entitled "54 Hours" was produced by the National Film Board of Canada.

A novel about the sinking by Tim B. Rogers titled The Mystery of the SS Southern Cross was published in 2014.

The loss of so many lives on Southern Cross has caused the incident to be written in a song entitled Southern Cross.

References

- Higgins, Jenny. "1914 Sealing Disaster". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Borchgrevink, Carsten (1901). First on the Antarctic Continent. George Newnes Ltd. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-905838-41-0.

- Jones, M. (2004). The Last Great Quest: Captain Scott's Antarctic Sacrifice. OUP Oxford. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-280570-6. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- "Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink (1864–1934)". Norway's Forgotten Explorer. Antarctic Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- "An Antarctic Time Line : 1519–1959". South-Pole. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- "Ships of the Polar Explorers". Cool Antarctica. Retrieved August 11, 2008. Fate of Nimrod and Aurora

- Paine, L.P. (2000). Ships of Discovery and Exploration. Ships of the World Series. Houghton Mifflin. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-395-98415-4. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Preston, D. (2012). A First Rate Tragedy: A Brief History of Captain Scott's Antarctic Expeditions. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-78033-081-5. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- "Death on the Ice: The Story That Had to be Told". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. Memorial University of Newfoundland. November 2000. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ""I Just Didn't Want to Die": The 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster". Our Collection. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

Bibliography

- Ryan, Shannon (1994). The Ice Hunters: A History of Newfoundland Sealing to 1914. Breakwater Books Ltd. ISBN 1-55081-095-2.

- Brown, Cassie (1972). Death on the Ice; the great Newfoundland sealing disaster of 1914. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-25179-3.

- "Tragedy on Ice". Maclean's. Vol. 113 no. 48. November 27, 2000. p. 76.

- Kent, Rockwell (1996). N by E. Wesleyan. ISBN 0-8195-5292-5.

- Wien, Jake Milgram (2014). Vital Passage: The Newfoundland Epic of Rockwell Kent. The Rooms, St. Johns, Newfoundland. ISBN 978-1-928156-00-0.