Saare County

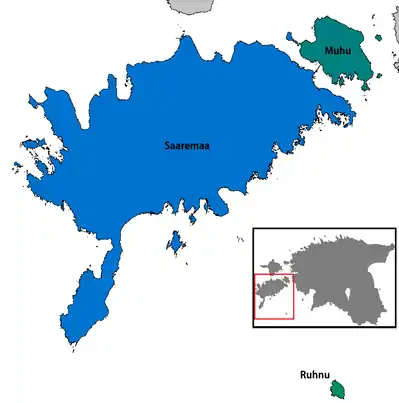

Saare County (Estonian: Saare maakond), or Saaremaa; (Latin: Oesel; German: Ösel) is one of 15 counties of Estonia. It consists of Saaremaa, the largest island of Estonia, and several smaller islands near it, most notably Muhu, Ruhnu, Abruka and Vilsandi. The county borders Lääne County to the east, Hiiu County to the north, and Latvia to the south. In January 2013 Saare County had a population of 30,966, which was 2.4% of the population of Estonia.[1]

Saare County | |

|---|---|

| |

Coat of arms | |

| |

| Country | Estonia |

| Capital | Kuressaare |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,922.19 km2 (1,128.26 sq mi) |

| Population (June 2017[1]) | |

| • Total | 34,041 |

| • Rank | 9th |

| • Density | 12/km2 (30/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Estonians | 98% |

| • other | 2% |

| ISO 3166 code | EE-74 |

| Vehicle registration | K |

Municipalities

The county is subdivided into municipalities. There are 3 rural municipalities (Estonian: vallad – parishes) in Saare County.

| Rank | Municipality | Type | Population (2018)[2] | Area km2[2] | Density[2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Muhu Parish | Rural | 1,946 | 206 | 9.4 |

| 2 | Ruhnu Parish | Rural | 160 | 12 | 13.3 |

| 3 | Saaremaa Parish | Rural | 31,819 | 2,705 | 11.8 |

Geography

The largest islands of the county are Saaremaa, Muhu, Ruhnu, Abruka and Vilsandi. Arable land is 570 km² and it has a mild maritime climate. The mean annual air temperature is 6.0 °C and the mean annual precipitation is 509 mm.

Religious affiliations

The main religious affiliations are Lutheran, Orthodox and Baptist, but only 33.6% consider themselves religious.[3]

Ancient Saare county (Oesel)

According to archeological finds, the territory of Saaremaa has been inhabited for at least five thousand years.

In the first centuries AD, political and administrative subdivisions began to emerge in Estonia. Two larger subdivisions appeared: the parish (kihelkond) and the county (maakond). The parish consisted of several villages. Nearly all parishes had at least one fortress. The defense of the local area was directed by the highest official, the parish elder. The county was composed of several parishes, also headed by an elder. By the 13th century, the following major counties had developed in Estonia: Saaremaa (Oesel), Läänemaa (Rotalia or Maritima), Harjumaa (Harria), Rävala (Revalia), Virumaa (Vironia), Järvamaa (Jervia), Sakala (Saccala), and Ugandi (Ugaunia).[4]

In old Scandinavian sagas, Saaremaa is called Eysysla which means exactly the same as the name of the island in Estonian: the district (land) of island. This is the origin of the island's name in German and Swedish, Ösel, Danish, Øsel, and in Latin Oesel. The name Eysysla appears sometimes together with Adalsysla, 'the big land', perhaps 'Suuremaa' or 'Suur Maa' in Estonian which refers to mainland Estonia. Sagas talk about numerous skirmishes between islanders and Vikings. Saaremaa was the wealthiest county of ancient Estonia and the home of notorious Estonian pirates, sometimes called the Eastern Vikings. The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia describes a fleet of sixteen ships and five hundred Oeselians ravaging the area that is now southern Sweden, then belonging to Denmark. In 1206, the Danish Valdemar II the Victorious built a fortress on the island but they found no volunteers to man it. They burned it down themselves and left. In 1227, Saaremaa was conquered by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, but remained a hotbed of Estonian resistance. The Order founded the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek there. When the Order was defeated by the Lithuanian army in the Battle of Saule in 1236, Oeselians rebelled. The conflict was ended by a treaty that was signed by the Oeselians and the Master of the Order.

The Oeselians along with the Curonians were known in the Old Norse Icelandic Sagas and in Heimskringla as Víkingr frá Esthland (in English, Estonian Vikings).[5][6][7][8] Their sailing vessels were called pirate ships by Henry of Livonia in his Latin chronicles from the beginning of the 13th century.[9]

Eistland or Esthland is the historical Germanic language name that refers to the country at the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea in general, and is the origin of the modern national name for Estonia. The mainland of modern Estonia in the 8th century Ynglinga saga was called Adalsyssla in contrast to Eysyssel or Ösyssla that was the name of the island (Swedish): Ösel or (Estonian): Saaremaa, the home of the Oeselians (Estonian: Saarlased). In the 11th century, Courland and Estland (Estonia) were both denoted separately by Adam of Bremen.[10]

On the eve of the Northern Crusades, the Oeselians were summarized in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle thus: "The Oselians, neighbors to the Kurs (Curonians), are surrounded by the sea and never fear strong armies as their strength is in their ships. In summers when they can travel across the sea they oppress the surrounding lands by raiding both Christians and pagans."[11]

Conquest of Saaremaa

In 1206, the Danish army led by king Valdemar II and Andreas, the Bishop of Lund landed on Saaremaa and attempted to establish a stronghold, but without success. In 1216 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the bishop Theodorich joined forces and invaded Saaremaa over the frozen sea. The following spring the Oeselians raided the territories in Latvia that were under German rule in revenge. In 1220, the Swedish army led by king John I of Sweden and the bishop Karl of Linköping conquered Lihula in Rotalia in Western Estonia. Oeselians attacked the Swedish stronghold the same year, conquered it and killed the entire Swedish garrison including the Bishop of Linköping.

In 1222, Valdemar II again tried to conquer Saaremaa, this time establishing a stone fortress housing a strong garrison. But the Danish stronghold was besieged, and surrendered within five days, and the Danish garrison returned to Reval, leaving bishop Albert of Riga's brother Theodoric and few others behind as hostages for peace. The castle was leveled to the ground by the Oeselians.[12]

In 1227, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, the town of Riga and the Bishop of Riga organized a combined attack against Saaremaa. After the surrender of two major Oeselian strongholds, Muhu and Valjala, the Oeselians formally accepted Christianity.

In 1236, after the defeat of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword in the Battle of Saule, military action on Saaremaa broke out again.

The Oeselians again accepted Christianity by signing treaties with the Master of Teutonic Order in Livonia Andreas de Velven and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek in 1241. The next treaty was signed in 1255 by the Master of the Order, Anno Sangerhausenn, and, on behalf of the Oeselians, by men whose "names" (or declaration) were transcribed by Latin scribes as Ylle, Culle, Enu, Muntelene, Tappete, Yalde, Melete, and Cake[13] The treaty granted several distinctive rights to the Oeselians. The 1255 treaty included clauses concerning the ownership and inheritance of land, the social system and autonomy from certain religious rules.

In 1261, warfare continued as the Oeselians had once more renounced Christianity and killed all the Germans on the island. A peace treaty was signed after the united forces of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek, and the forces of Danish Estonia, including mainland Estonians and Latvians, defeated the Oeselians by conquering the Kaarma stronghold. Soon afterwards, the Teutonic Knights established a stone fort at Pöide.

On July 24, 1343, the Oeselians again killed all the Germans on the island, drowned all the clerics and started to besiege the fort at Pöide. After its surrender, the Oeselians levelled the castle and killed all the defenders. In February 1344, Burchard von Dreileben led a campaign over the frozen sea to Saaremaa. The Oeselians' stronghold was conquered and their king Wesse was hanged. In the early spring of 1345, the next campaign of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order took place; it ended with a treaty mentioned in the Chronicle of Hermann von Wartberge and the Novgorod First Chronicle. Saaremaa remained the vassal of the master of the Teutonic Order in Livonia, and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek.

Gallery

References

- "Population by sex, ethnic nationality and County, 1 January". stat.ee. Statistics Estonia. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- "Elanike demograafiline jaotus maakonniti". Kohaliku omavalitsuse portaal. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- 2000 Population and Housing Census. IV. Education Completed. Religion. Estonia: Statistics Estonia. 30 May 2002. p. 32. ISBN 9985-74-220-6. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- Raun, Toivo (2001). Estonia and the Estonians. Hoover Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-8179-2852-9.

- (in Norwegian) Olav Trygvassons saga at School of Avaldsnes Archived 2008-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Heimskringla; Kessinger Publishing (March 31, 2004); on Page 116; ISBN 0-7661-8693-8

- A History of Pagan Europe by Prudence Jones; on page 166; ISBN 0-415-09136-5

- Nordic Religions in the Viking Age by Thomas A. Dubois; on page 177; ISBN 0-8122-1714-4

- The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia ISBN 0-231-12889-4

- History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen By Adam of Bremen Page 196-197

- The Baltic Crusade By William L. Urban; p. 20 ISBN 0-929700-10-4

- The Baltic Crusade By William L. Urban; p 113-114 ISBN 0-929700-10-4

- Liv-, est- und kurländisches Urkundenbuch: Nebst Regesten

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saare County. |

- Saare County Government (in Estonian)

.jpg.webp)