Sam Byrne (painter)

Samuel Byrne was an Australian naïve painter and folk historian who visually chronicled the rise of Broken Hill, from its frontier days right through to the establishment of a modern city. Without any formal training, Byrne took to painting when he was in his seventies after retiring from a lifetime working on Broken Hill's mines. His detailed, narrative-centred approach to landscape painting was discovered by Leonard French, who brought him to the attention of Sydney and Melbourne's art connoisseurs. Byrne is best known for painting subjects that held a personal fascination for him; Broken Hill's rabbit plagues, Sturt's desert peas, dust storms, industrial riots, and pioneering mining scenes.[1] As a trade unionist and having first hand experience of the harsh mine conditions, his works are often imbued with a working-class consciousness and show a deep sensitivity to the plight of the victimised. Although he was often compared to Grandma Moses and other painters in the naïve school, as James Gleeson writes, Byrne "paints in a manner that is so consistent that we are obliged to acknowledge it as a personal style."[2]

Sam Byrne | |

|---|---|

Sam and Florence Byrne in 1915 | |

| Born | Michael Eldrige Samuel 10 July 1883 |

| Died | 24 February 1978 (aged 94) |

| Resting place | Broken Hill Cemetery |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Painter |

| Years active | 1955-1978 |

| Known for | Naïve art, Folk Historian |

| Spouse(s) | Florence Byrne |

| Signature | |

| |

Of Sam Byrne, John Olsen wrote "no [other] Australian painter has portrayed, with such enduring simplicity and humanity, the world of the 1890s."[3] Elwyn Lynn described the folk painter as a "raconteur in paint".[4] James Gleeson described him as a "genuine primitive", an "innocent of art", whose visual experience has not been filtered by conceptions of style or technique.[5]

Early life and mining career

Early life

Sam Byrne was born Michael Eldrige Samuel, the second child of James and Elizabeth Burns, on 10 July 1883, in Humbug Scrub, South Australia in the Barossa Valley, South Australia.[6] His Irish-born father was an itinerant worker who travelled between various Australian gold and silver rushes, seeking out fortune. His mother was Australian born. The pair met and married in the Barossa Goldfields, where they conceived their first two children. Prior to Sam Byrne's birth, his father had left to join the short-lived Mount Brown gold rush in Northern New South Wales.[7] Following that, he joined the silver rush on the Barrier District, where he worked as a blacksmith on the Daydream and Umberumberka silver mines. When Sam Byrne was two years old, his father returned and relocated the family to the small silver mining town of Thackaringa, west of Broken Hill.[8]

The next few years of Sam Byrne's life saw the birth of three more brothers. He attended a primary school in Thackaringa, which was later destroyed by a storm.[9] In 1890 his father died from an injury incurred whilst shoeing a horse.[8] The absence of widow's pensions at the time left Sam Byrne's mother with no means to support her young sons. She made the decision to move the family East to Broken Hill, where she could earn income as a washerwoman. Housed in a canvas hut without heating, and working long hours, she soon succumbed to pneumonia.[10] Byrne and his siblings were then adopted by two of his married aunts. He was sent to the Broken Hill Central Primary School, where he remained until he was old enough to work on the mines.[8] A further family disruption occurred when his foster uncle abandoned the family for the Western Australian gold rush. He was never heard from again.[11] To support the family, Byrne's foster aunt then took to washing duties, whilst Sam Byrne sold newspapers and collected bottles.[12] Another income stream for Sam Byrne came during the great rabbit plagues of 1895–1896. The municipal council, incorrectly thinking that dead rabbits were causing a typhoid epidemic, paid rewards to children who collected the carcasses off the streets. Byrne recalls with fondness filling prams and wheelbarrows full of rotting rabbits to take to the council.[13] Later in life, Byrne would become well known amongst art collectors for his paintings of rabbit plagues.[14]

Mining career

At the age of fifteen Sam Byrne started work on the BHP Mine, a company in whose service he would remain for the next fifty-one years. His employment was crucial to financially support his family following the sudden death of his older brother from pneumonia. Byrne was underage, however was admitted upon presenting his late brother's union registration card.[15] Initially working as a messenger boy, around the age of seventeen he took on the hard labour of men's work: Breaking rock with picks, boring, timbering, shovelling ore into trucks and then pushing them along the drives to the shafts.[8] He experienced harsh working conditions: hot and dusty mine shafts, no water, underground fires. Workmates were killed by falling rock, or poisoned from touching and breathing lead ore.[12][16] Byrne himself narrowly escaped several cave-ins as the result of inadequate amounts of timber reinforcements being used on the mine stopes.[12][17] Whilst engaged in hard labour, he often felt worried he would meet the same untimely death from miner's diseases or an accident as his workmates did.[12] He has criticised the mining companies for their "heartless" treatment of workers in the early days; "when a man got killed he was sent straight to the morgue [but] if a horse got killed there was a hell of an inquiry a horse was far more important than a man."[18][19]

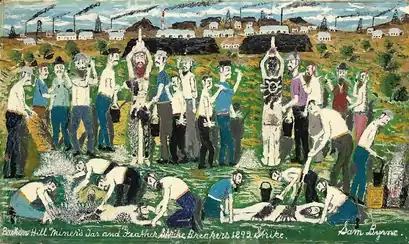

Byrne was witness to several industrial disputes between Broken Hill's mine labourers and mining companies. As a nine-year old child he recalls the 1892 strike, triggered by proposed wage reductions as a result of low metal prices. To replace the striking workers, the mining companies brought in cheap labour "scabs" from South Australia and Victoria. This led to the workers losing the strike and accepting a wage reduction.[12] Byrne and his childhood friends used to throw rocks on the houses of the scabs, and trip up mine officials who were delivering anti-union newspapers.[20] He witnessed the striking miners, which included his foster uncle, capturing the scabs and subjecting them to a ritual of public humiliation, whereby they were covered in hot tar and feathers.[21][8] His paintings of this event, unique in Australian art, have been likened to medieval retribution paintings; gestures of social justice.[22]

Another industrial dispute in 1909 resulted in the closure of two of Broken Hill's major mines, leaving over a thousand men without work. Byrne was working on a mine unaffected by the lockout. English socialist Tom Mann was brought into Broken Hill to act as an industrial organiser.[12] G. D. Delprat, the general manager of BHP, in anticipation of riots, contacted the New South Wales premier Charles Wade, requesting police reinforcements to be sent from Sydney.[23] Sam Byrne played in his union brass band, which lead the pickets in procession to the mine boundary.[8] He was part of the audience of spectators who witnessed the police attack the procession of the locked-out miners.[24] The riot culminated in the arrest of Tom Mann; the miners had lost their struggle.

In 1908, on a sojourn to South Australia to work as a labourer on a salt pan, Sam Byrne courted his cousin Florence Pope. Florence came from a farming family along the banks of the Murray River.[25] After exchanging letters over the coming years, she moved to Broken Hill and the couple married with Anglican rites in 1910.[6] They bought their first house in the suburb of Railway Town, next to Byrne's foster aunt's house. The house was destroyed by a fire in 1911.[26] Over the next few years, the couple had three sons.[27]

Just before the outbreak of the First World War, Sam Byrne had a near death experience underground when his arm was savaged in a piece of machinery. The resulting injuries were severe enough to put him out of work for a whole year. Whilst recuperating at home, Byrne decided that continuing underground labouring work was too dangerous, and so he studied to gain work as a surface engine driver. He joined the Federated Engine Drivers' and Firemen's Association (FEDFA) union.[28] It was the security of this specialised trade that meant he was insulated from the economic downturn of the great depression.[29] Sam Byrne did not enlist to join the war effort due to his injury and domestic responsibilities. His youngest brother did enlist and was killed at Gallipoli.[28]

Byrne secured scholarships to send his three sons to a teacher's college; adamant that they would not go to dangerous work on the mines.[30][31] When the Second World War started, Byrne did not enlist for military service because mining was a protected industry.[32] He retired from the mines in 1949 at the age of sixty-six, when he became eligible for the old-age pension.[33]

Career as a painter

Sam Byrne's earliest artistic endeavours took place underground, where he would sketch scenes onto timbers deep in the mines where he worked.[30] In his retirement, excursions with the Old Age Pensioners Association, the Broken Hill Historical Society, and the Field Naturalists Society provided Sam Byrne the opportunity to revisit the arid landscapes and ruined mines of his childhood.[34] A technically astute drawer, he would make sketches of the scenery because he wanted some mementos of the outback to take home. It was at some point in the early 1950s when Byrne first dabbled with making paintings of his sketches. Without any commercial motivations, he started simply because he thought they'd be nice to have hanging on the walls at home.[35]

Sam Byrne

Sam Byrne's first forays into public exhibition took place after he viewed an art exhibition in Broken Hill and was unimpressed by the modernist style entries. He remarked to his brother that he thought he could create better paintings. His brother scoffed at the idea, and so Byrne rose to the challenge.[37] At the following year's art competition, he submitted two works in poster paints on butcher's paper. Although he did not win a prize, his entries were highly commended by the judge. The judge, wanting to ensure Sam Byrne had every opportunity to improve on his materials and technique, referred him to the guidance of Florence May Harding.[37] Harding was a commercial artist and art teacher at the Broken Hill Technical College, having taken her alma mater at the National Art School in Sydney.[38] Becoming a family friend, she introduced Byrne to the requirements of being a professional artist and encouraged him to continue painting in his own characteristic style. For the next few years he continued to enter the annual Broken Hill art competition, and received prizes each year.[39]

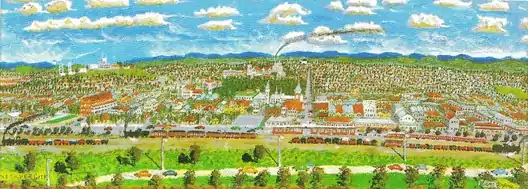

In 1960, the annual art competition was judged by Melbourne artist Leonard French. Without any hesitation, French awarded Sam Byrne first prize for his panorama of the Broken Hill township. French recalled it "had the absolutely beautiful quality of naïve painting."[40] There was a feeling of resentment amongst the other entrants, who could not comprehend why an untutored artist continued to receive the top prizes.[40] French was so impressed by Byrne that he offered to promote his paintings to Rudy Komon, a major contemporary gallery director in Paddington, Sydney.[41]

Byrne's first commercial exhibitions were swiftly organised, showing in group exhibitions in 1960 alongside works by Gil Jamieson - first at Melbourne's Museum of Modern Art of Australia, then touring up to Paddington's Rudy Komon Art Gallery.[42] Opening the Rudy Komon show was dignitary Sir Edward Warren, chairman of the Colliery Proprietors' Association.[43] In a first public acquisition, Hal Missingham, director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased one of Byrne's landscape paintings for the gallery's permanent collection.[44] In 1963, Byrne's eightieth year, he was given his first one-man show at Rudy Komon Art Gallery, where he exhibited 45 works. The solo exhibition was commercially successful, many works selling within the first two hours.[45] To meet demand, Byrne painted two additional rabbit plague paintings while on location in Sydney.[46] Critical attention was also garnered from Sydney's top art critics, James Gleeson and Elwyn Lynn, both publishing generally favourable newspaper reviews.[4][2] The following year, a Sam Byrne painting was featured on the cover of Art and Australia, in which John Olsen wrote of the contribution of several naïve painters to Australian art.[3]

Due to declining health and concern over the income affecting his old age pension,[47] Sam Byrne only committed to a few more commercial exhibitions in the major cities.[48] His last solo exhibition was at Rudy Komon's in 1966.[49] It was around this time that there was a sudden demand for the work of Broken Hill artists. The demand was attributable to a yearning to discover a new nationalist pictorial language based on the arid landscapes of the outback.[50] Despite a withdrawal from exhibiting in commercial galleries, Byrne still found plentiful buyers in the form of tourists and gallery agents who would visit his Broken Hill home gallery in Wolfram Street.[51] Buying directly from the Byrne's proved lucrative for dealers, who could re-sell the purchased work for treble the price.[52]

To oblige those who could not travel to Broken Hill, a mail order service was set up. Due to the overwhelming demand, Florence Byrne out of necessity stepped into a role as her husband's manager. She managed a host of mail order inquiries, managed financial transactions and negotiated with art dealers.[53] Helped by continuing liaison with Rudy Komon, Byrne's paintings were sourced and acquired into many private and corporate collections worldwide.[54] A long time buyer and personal correspondent was the art collector Margaret Carnegie.[55] During this period of high buyer demand, Byrne found that certain scenes were more commercially successful. He had no qualms about revisiting these particular scenes, such as his rabbit plagues, producing dozens of copies with only slight variations.[56] Byrne was also happy to take commissions for family history paintings from prominent society members whose ancestors had an important connection to Broken Hill.[57] Amongst these commissions was a descendant of Charles Sturt,[58] the artist Paul Delprat,[59] and Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt.[60]

Beginning in 1961, Sam Byrne was a founding member and frequent exhibitor of the Willyama Arts Society; a Broken Hill initiative to encourage local artists and exhibitions.[61] He was a respected member for his contribution to policy making and his efforts to promote it outside of Broken Hill.[62] In 1973 a group of Broken Hill painters including Pro Hart, Jack Absalom and Hugh Schulz formed a charitable business group known as the Brushmen of the Bush. The group quickly found fame through the attentions of celebrities and a Qantas sponsorship to promote overseas their paintings of the Australian outback. Despite a close friendship with Hart and Schulz, Sam Byrne was never asked to join the Brushmen. This exclusion negatively affected Byrne's commercial saleability. Both the Brushmen of the Bush and Sam Byrne had their names registered at the Broken Hill Tourist Bureau, yet the Brushmen's galleries were the popular first port of call for the tourists.[63]

Sam Byrne

In 1970 Broken Hill's mayor awarded Sam Byrne a certificate in recognition of his services to art. His works were mounted in a short exhibition at the Broken Hill Regional Gallery. When the gallery did not purchase any for their permanent collection, Byrne offered to donate them. The gallery refused the offer.[64] During the last few years of his life, the artist concentrated on painting a singular vision: a series of epic panoramas of the Broken Hill Line of Lode[65] as he had remembered it from his childhood. With this subject matter he won two major acquisitive art awards; first in 1976 for the Broken Hill Regional Gallery, and in 1977 for the Swan Hill Regional Gallery. Following the latter acquisition, the director of the Swan Hill Regional Gallery decided to make collecting primitive art the new focus for the gallery going forward.[66] Byrne was also a finalist in the Art Gallery of New South Wales' 1977 Wynne Prize for landscape painting, from which his painting of the BHP Mine and smelters was purchased by BHP for its Melbourne offices.[67]

A spate of publicity followed the prizes. Byrne was featured in two art theory books on Australian naive painters,[68][69] as well as a television documentary broadcast on the ABC.[13] There was a resurgence of interest from commercial galleries. Byrne allowed a single gallery director to buy up a significant portion of the family's private collection,[70] despite his wife's earlier insistence that these paintings would never be sold.[48] Despite failing health, and determined to win a third acquisitive prize, Byrne embarked on one last panorama to immortalise the Broken Hill landscape of his childhood. The epic seven foot painting was entered into the annual art competition. The artist was too frail and ill with hernias to ascend the gallery steps to see the painting hung. It was not awarded any prizes and the gallery did not purchase it, instead going to an Adelaide gallery director. It was the final painting Sam Byrne exhibited.[71]

Ill health and death

In 1971, Sam Byrne had a fall in a bathtub whilst on holiday in Rotorua, New Zealand.[72] In 1973 he underwent an emergency operation to fix a stomach blockage. Unlikely to survive the anaesthetic, he sung a final tribute song to Ireland on the operating table before going under.[73] Miraculously, having survived the operation, he returned home to paint. His output declined in the last few years, struggling with glaucoma and arthritis. In private letters to gallery owner Rudy Komon, Byrne confessed his worry about not being able paint for much longer due to his eyesight.[74] In his last years, he struggled through Broken Hill's hot summers, spending only a few hours a day crouched in his rusty shed over his paintings.[75] "It is here that I would like to die, at my easel" he once said.[76] By late 1977 the artist had to undergo another operation and was losing his stamina and appetite. In February 1978, the gravely-ill Sam Byrne was hospitalised. He died on 24 February 1978, unconscious and in no pain.[77] He was interred at Broken Hill Cemetery.[6] His funeral was poorly attended.[20] Following his death, Broken Hill's Barrier Daily Truth published only a brief death notice.[77] Some months later, the Sydney Morning Herald published a lengthy obituary and lamented that the artist's death had been unmourned by the very city he had "helped build from the very bowels of the earth."[76]

Technique, style, and themes

Early works (1955–1962)

From his childhood, Byrne had a fascination with maps and mapmaking.[31] The works produced at the beginning of his artistic career are reminiscent of cartographic style.[78] The cartographic impulse continued through his oeuvre, manifesting in his use of line, colour, his feel for space and his interest in the man made aspects of the desert landscape such as railway tracks and roads.[79] His earliest documented paintings, dating from the late 1950s, take the form of detailed, large-scale panoramas of the Broken Hill township as it appeared from atop the Line of Lode. The works bear a striking resemblance to the early topographical drawings of Australia's colonial settlements.[80] There is a focus on technical observedness, reflecting Byrne's desire to document his township exactly as he saw it, without taking any artistic liberties. Despite the need for accuracy, Sam Byrne never painted his townscapes en plein air.[40] Instead he preferred to make pencil sketches on location directly onto the masonite, noting down colours.[8] He would then paint over them at home, where he worked in an old tin laundry on the side of his house.[20] To achieve the detailing on distant buildings and trees, the artist used a technique similar to pointillism.[80] Author Geoffrey Lehman describes the technique as "miniaturisation", observing that the tiny houses "congregate and accrue like a colony of coral polyps."[81] Taking around 3 weeks to complete,[48] fewer than ten panoramas are thought to have been created. Byrne would later suffer from failing eyesight and, out of physiological necessity, move on to subjects less concerned with microscopic finesse and the conventions of technical draughtsmanship.[82]

Mid career (1962–1975)

Broadly speaking, the body of work from Sam Byrne's middle period depicts his memories of the early days of Broken Hill. With a focus on the life of miners, civic and domestic life, as well as key events, Byrne's paintings were often stories drawn from his own folk experience. Art critics were early to realise the associations between Byrne's visual narrative style, the folk anecdote, and the literary genre of the bush ballad.[50] Providing a basis to each narrative, each of Sam Byrne's paintings characteristically have an explanatory title printed in the lower left hand corners. Describing this, the artist said "A painting has to tell a story. That's why I write the title in. I write a lot across the bottom of my paintings because I want people to know about the history of the place."[83] Not an admirer of contemporary art, Byrne only enjoyed paintings in which the meaning was transparent to him.[8]

Structurally, Byrne's narrative paintings from the 1960s onward abandon the realism of orthodox painting that he strove for in his early Broken Hill panoramas. He began to mostly ignore the laws of diminishing perspective, in a way stylistically reminiscent of early Renaissance art.[84] In reviews of Byrne's first solo exhibition, John Olsen and James Gleeson both felt that Byrne seemed simply not aware of the existence of technical problems within his compositions.[3][2] Byrne would structure his paintings according to the elements of the narrative he wished to tell.[20] He would use distortions and magnifications to emphasise the importance of particular objects within a landscape or narrative. Sometimes he distorted buildings in a way which displays multiple sides from the same perspective.[85] His Sturt pea landscapes are an example of the use of magnification: a tiny prostrate flower in reality, is given gigantic proportions against the surrounding landscape.[35] In other occasions, cartoonish manipulations of human proportions have been used for comic effect.[86] John Olsen observes that another aspect of Byrne's "unusual spacial abilities" is his use of impasto on foreground objects that he considers more important in the schema.[3]

Sam Byrne has been considered an innovator in his approach to solving the problems of painting the Australian interior.[20] Despite having parallels with mainstream artists, his techniques are notable in that Byrne developed them in geographic isolation; with no lessons nor access to textbooks about painting.[44] James Gleeson, in reviewing a Sam Byrne exhibition, wrote of charming results when untutored artists like Byrne provide their own solutions to pictorial problems without relying on the conventions taught at art schools.[87] The featureless, flat expanse of the Australian outback presented a problem for painters in the pastoral tradition, as it lacked picturesque props such as trees or foreshores to make the images interesting. Byrne solved this problem by a compression of vision, not unlike the approach used by Fred Williams.[20] His paintings often show a tilting of the landscape; relegating the horizon and sky to the upper quarter of his compositions. With a larger land area, Byrne filled the landscape with the objects and characters of his narrative. In substitution of trees, so sought after by the pastoralists, Byrne uses the structures of early mining equipment.[88] In painting surface detail such as rocks and vegetation, Sam Byrne also has parallels with artist John Olsen. Both artists use abstracted forms such as blobs and squiggles to capture the essence of the outback landscape.[20]

Warm colour palettes, enhanced by gloss varnish are a characteristic of most of Sam Byrne's middle period. He deployed colour in a bold way that helped achieve harmony, pattern, and a sense of balance in his compositions.[66] In scenes showing cut-away earth, all possible earthy colours are used, sometimes arranged like rainbows, capturing Broken Hill's rich veins of mineral deposits. For above-ground scenes, textured yellow ochres are contrasted against the artificially bright red used for Sturt's pea flowers and vegetation.[81] His skies are almost always clear and chalky blue, populated by well defined cumulus clouds resembling "surreal zeppelins".[89] Byrne would usually paint the sky first and then work his way down to the foreground.[81] John Olsen likened Sam Byrne's colour schemes to Breughel: "he delights in cherry reds, happy colours [which] dance over the picture plain with glee and wonder."[3] In many paintings depicting lead mining, Byrne sprinkled actual galena dust (lead ore) into the wet paint to represent where galena is being depicted. The dust provides an additional tactile and sparkly quality to the compositions; becoming somewhat stellar when used in underground scenes. Although the use of galena dust has been described as "a bizarre urge for realism" resulting in an unnatural appearance, Byrne felt the look it achieved was completely truthful to nature.[79][90]

Crowd scenes depicting town life in the early days of Broken Hill are a recurrent theme in Sam Byrne's repertoire. So too are scenes of violent struggles between striking miners and law enforcement authorities; often watched on by townsfolk spectators. Sam Byrne's characteristic treatment of crowds is to paint giving frontality to human figures.[4] By painting all characters facing the viewer, Byrne achieved a means to convey their emotional reaction to the folk story that is being depicted.[85] Although his faces tend to be crude and cartoonish, the subtle positioning of dots in a character's eyes still manages to evoke their distinct emotional states. Painting the correct facial expression was of importance to Byrne; often his faces would build up like impasto in multiple attempts at achieving the correct state.[60] Comparison has been drawn between Byrne's figures and the crowds in the London streetscapes of L. S. Lowry.[91] For author Geoffrey Lehmann, Byrne's figures appear "puppet like", as if all actors on a staged narrative, small and standardised against a dominating landscape, and rarely with any emphasis on any individual figure.[92]

Final years (1975–1978)

In the last few years of his life, Byrne was suffering from arthritis and glaucoma. His output declined. A hole at the centre of his vision meant he could not discern the details of what he wished to paint.[93] Troublesome too were colours, which were impossible to distinguish between without the help of a friend who would organise the paint pots into an order for him.[65] Paintings produced during this period are described as having a certain abstracted quality,[94] crude in individual elements but possessing immense energy in their total effect.[13] Thematically, the last few years of life saw Byrne concentrate obsessively on painting long epic panoramas of Broken Hill's Line of Lode as he remembered it from the pioneering era.[65] The larger scale of these works allowed Byrne, almost blind, to perceive enough detail and was more accommodating to irregularity of lines and forms.[95]

Sam Byrne's first painting medium was watercolour. Due to the impracticalities of shipping paintings with glass, he abandoned the medium in the early 1960s.[53][16] For the most part of his career, Byrne painted with a mixture of oils and synthetic gloss enamels. He would often outline in the thicker oil paint and then fill using enamels.[60] Dulux house paints were his preferred medium for clouds and skies on account of the shine and brilliance they afforded.[16] In the latter years the artist switched to the exclusive use of Dulux and Taubman's gloss enamels. The slippery nature of this new media led to a shift in painting technique. Forms were no longer outlined; paint was tipped on and then spread into position.[96] To prevent the paint running, Byrne would paint with the board lying flat upon his bench.[20]

Sam Byrne developed his own unique aesthetic to express the proliferation of mines and smelters upon the barren landscape in the early days of Broken Hill. His accurate recollection of the pioneering mining processes is reflective of knowledge gained through a close working relationship with the machinery across his lifetime. Author Ross Moore compares Byrne's mining panoramas to the industrial landscapes of Jan Senbergs, saying both express a "machine romanticism" in the love of architectural forms of industry.[88] Particularly in his final Line of Lode paintings, the artist made use of certain structures in the mining industry that provide strong vertical and horizontal lines. These have the effect of intersecting the picture planes, drawing the viewer's eye through the composition. Such vertical structural devices included poppet heads, smelter stacks, and red streams of molten slag being poured. Horizontal structural devices included railway bridges, cross-sectional views of mines, and drifting smoke plumes which bend at right angles to the tops of smelter chimneys.[88]

Political and religious views

Like many Broken Hill miners who lived through the decades of union militancy so formative to trade unionism in Australia, Sam Byrne declared himself to be a socialist. As a young man he prolifically read socialist literature, including the works of Marx and Engels, that he had obtained through his union.[23] Of his political preferences, he declared "I think everybody would have a better living if the government controlled everything and instead of dividends going overseas [all the profits] would be returned to the people."[18] He praised English socialist Tom Mann, who came to Broken Hill as a union organiser, as a being "great man – a true blue unionist fighting for the worker".[19] Sam and Florence Byrne had a political opposition to war and were against conscription.[97] Of his opposition to the Vietnam War, Byrne said "well if communism came to America the millionaires would have to give up their millions and start doing something useful."[98]

Sam Byrne's religious views were pantheistic. He believed somewhat in Darwinism, somewhat in cosmic creationism. On the other hand, he thought the biblical story of creation was fictitious. He would argue with clergymen about their religious views.[99] Despite this, he would sometimes paint Broken Hill's churches, and attend church ceremonies with his wife Florence.[100] Byrne was also against missionaries interfering in Australia's indigenous society.[99]

Legacy

In 1985, artist Ross Moore published Sam Byrne: Folk Painter of the Silver City, dedicated to profiling the life and art of Sam Byrne. In 1977 Moore had travelled to Broken Hill to meet and interview the artist. One of book's key arguments is that Sam Byrne's overwhelming legacy is his value as a folk historian; a chronicler of the social character of Broken Hill over time. In Moore's opinion, Australia had been lacking in consciousness of the history of colonial settlement in far Western New South Wales. As the last of his generation, Sam Byrne's connection to the pioneering silver rush of the Barrier District opened a window to the past that was on the verge of being forgotten. His strike paintings in particular are historically significant to researchers of early trade unionism in Australia. They are unparalleled anywhere else in Australian art, and scarce photographic records remain of some of the events depicted.[20] As an insight into historic mining techniques, Sam Byrne has provided the fullest visual history of the underground working environment, from the colonial days of candlelight, picks and hammers, to the electric lights and pneumatic drills of modern mining.[101] Ross Moore expressed disbelief that, although Byrne's paintings were clearly historical documents of the growth of mining and civic life in Broken Hill, BHP and the Broken Hill City Council had consistently failed to buy more for their collections.[20]

Collections

Works by Sam Byrne are held in the permanent collections of the

- National Gallery of Australia

- Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Queensland Art Gallery

- National Gallery of Victoria

- Heide Museum of Modern Art

- Newcastle Art Gallery

- Mildura Arts Centre

- Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery

- Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery

References

- Moore, p. 5

- Gleeson, James (28 July 1963). "'Primitive' Art and Sam Byrne". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney.

- Olsen, John (May 1964). "Naive Painters". Art and Australia. Sydney: Ure Smith.

- Lynn, Elwyn (28 July 1963). "Honesty of Innocence". Sunday Mirror. Sydney.

- Gleeson, James (12 October 1960). "Pictures Reveal Influence". The Sun. Sydney.

- Grishin, Sasha. "Byrne, Samuel Michael (1883-1978)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Moore, pp. 15-16

- Byrne, Sam (narrator) (20 June 1967). Broken Hill Memories by Sam Byrne. ABC Radio.

- Moore, p. 38

- Moore, p. 51

- Moore, pp. 52

- O'Neil, William; Riddiford, Wally; Eriksen, Bill; Byrne, Samuel; Dwyer, Thomas John (1974). "Five miners involved in the Broken Hill Miner's Strike of 1919". Not broadcast (Held in oral history collection at National Library of Australia) (Interview). Interviewed by M. Laver. Recorded in Broken Hill.

- Garner, Stafford (Director) (1978). "Australia". Art from the Heart: Naïve Painters. ABC Television.

- Allison, Colin (Uncredited) (24 October 1972). "From Miner to Famous Primitive". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney.

- Moore, p. 69

- Lehmann, p. 72

- Moore, p.78

- Lehmann, p. 75

- "Mine Veteran's Fine Paintings of Broken Hill". Common Cause. Sydney: Australasian Coal and Shale Employee's Federation. 24 August 1963.

- Ravlich, Robyn (host) (27 April 1988). "Sam Byrne". Wednesday Feature. ABC Radio National.

- Moore, p. 85

- Moore, p.87

- Moore, p.91

- Moore, p.98

- Moore, p. 104

- Moore, p. 153

- Moore, p.107

- Moore, p. 108

- Moore, p. 111

- Scholer, Pat (25 September 1963). "The Good Oil on Broken Hill". People. Sydney: Associated Newspapers Ltd.

- Lehmann, p. 67

- Moore, p. 112

- Moore, p. 118

- Moore, p. 121

- Moore, p. 122

- Moore, p. 4

- Moore, p. 124

- Lumbers, Eugene (1977), The art of Pro Hart, Rigby, ISBN 978-0-7270-1563-1

- Moore, p.126

- Moore, p.128

- Moore, p.133

- Moore, p.134

- Castle, Ray (13 October 1960). "A Rival for Grandma". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney.

- Munday, Winifred (23 November 1960). "Grandpa (Moses) Byrne". The Australian Women's Weekly. Sydney: Australian Consolidated Press.

- Moore, p. 136

- Moore, p. 140

- Letter from Byrne, Sam 4 December 1967 in Komon, Rudy & Rudy Komon Art Gallery (1959) Records of the Rudy Komon Art Gallery 1950-1984 [unpublished manuscript (Held at National Library of Australia)]

- Seager, Helen (25 January 1965). "Miners with Golden Paintbrushes". Woman's Day with Women. Melbourne: Herald and Weekly Times.

- Moore, p 150

- Moore, p. 142

- Moore, p. 143

- Moore, p. 160

- Moore, p. 151

- See correspondence in Komon, Rudy & Rudy Komon Art Gallery (1959) Records of the Rudy Komon Art Gallery 1950-1984 [unpublished manuscript (Held at National Library of Australia)]

- See letters from Byrne, Sam. in Carnegie, Margaret. (1960) Papers of Margaret Carnegie c. 1960-1980 [unpublished manuscript (held in State Library of Victoria)]

- Moore, p. 138

- Lehman, p. 64

- "Did Painting for Sturt Descendant". Broken Hill Miner. Broken Hill. 29 September 1969.

- Moore, p. 101

- Moore, p.156

- Rost, Fred. "Florence May Harding b. 1908". Design & Art Australia Online. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Moore, p. 145

- Moore, pp.174-175

- Moore, p. 180

- Moore, p. 182

- Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery; Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum; Orange Regional Gallery; Monash Gallery of Art; Coffs Harbour City Gallery; Wangaratta Exhibitions Gallery; Tamworth Regional Gallery; Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery (2004), Raw and compelling : Australian naive art - the continuing tradition : a Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery travelling exhibition supported by NETS Victoria, Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery, ISBN 978-0-9590560-3-7

- Letter from Byrne, Sam c. 1977 in Komon, Rudy & Rudy Komon Art Gallery (1959) Records of the Rudy Komon Art Gallery 1950-1984 [unpublished manuscript (Held at National Library of Australia)]

- McCullogh (1977)

- Lehmann (1977)

- Moore, p. 183

- Moore, p 187-188

- Letter from Byrne, Sam 2 February 1971 in Komon, Rudy & Rudy Komon Art Gallery (1959) Records of the Rudy Komon Art Gallery 1950-1984 [unpublished manuscript (Held at National Library of Australia)]

- Moore, p. 172

- Letter from Byrne, Sam 17 September 1973 in Komon, Rudy & Rudy Komon Art Gallery (1959) Records of the Rudy Komon Art Gallery 1950-1984 [unpublished manuscript (Held at National Library of Australia)]

- Moore, p. 192-193

- Allison, Colin (6 May 1978). "Sam Byrne: In Memorium". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney.

- Moore, p. 195

- Lehmann, p.63

- McGrath & Olsen, p. 162

- Moore, p. 131

- Lehmann, p. 64

- Moore, p.130

- Moore, p.168

- Moore, p. 3

- Moore, Ross, 1954-. Letter to Len Fox [unpublished manuscript] Papers of Len Fox 11 January 1981 [held at State Library of NSW]

- Moore, p. 35

- Gleeson, James (8 June 1966). "Landscape Variety". The Sun. Sydney.

- Moore, p. 64

- Moore, p. 187

- Lehmann, p. 82

- Moore, p57

- Lehmann, p. 63

- Moore, p. 164

- McCullough, p.30

- Moore, p.179

- Moore, p. 177

- Moore, p.108

- Fox, Len. Notes on Interview with Sam Byrne [unpublished manuscript] Papers of Len Fox August 1963 [held at State Library of NSW]

- Moore, p. 189

- Lehman, p.68

- Moore, p. 71

Referenced books

- Lehmann, Geoffrey (1977), Australian primitive painters, University of Queensland Press, ISBN 978-0-7022-1039-6

- McGrath, Sandra; Olsen, John (1981), The artist & the desert, Bay Books, ISBN 978-0-85835-497-5

- Moore, Ross (1985), Sam Byrne, folk painter of the Silver city, Viking ; Ringwood, Vic. : Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-006428-5

- McCullough, Bianca (1977), Australian naive painters, Hill of Content, ISBN 978-0-85572-081-0