Galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.[4]

| Galena Lead glance | |

|---|---|

Galena with minor pyrite | |

| General | |

| Category | Sulfide mineral, octahedral subgroup |

| Formula (repeating unit) | PbS |

| Strunz classification | 2.CD.10 |

| Dana classification | 2.8.1.1 |

| Crystal system | Cubic |

| Crystal class | Hexoctahedral (m3m) H–M symbol: (4/m 3 2/m) |

| Space group | Fm3m |

| Unit cell | a = 5.936 Å; Z = 4 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Lead gray and silvery |

| Crystal habit | Cubes and octahedra, blocky, tabular and sometimes skeletal crystals |

| Twinning | Contact, penetration and lamellar |

| Cleavage | Cubic perfect on [001], parting on [111] |

| Fracture | Subconchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 2.5–2.75 |

| Luster | Metallic on cleavage planes |

| Streak | Lead gray |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 7.2–7.6 |

| Optical properties | Isotropic and opaque |

| Fusibility | 2 |

| Other characteristics | Natural semiconductor |

| References | [1][2][3] |

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crystallizes in the cubic crystal system often showing octahedral forms. It is often associated with the minerals sphalerite, calcite and fluorite.

Lead ore deposits

Galena is the main ore of lead, used since ancient times. Because of its somewhat low melting point, it was easy to liberate by smelting. It typically forms in low-temperature sedimentary deposits.

In some deposits the galena contains about 1–2% silver, a byproduct that far outweighs the main lead ore in revenue. In these deposits significant amounts of silver occur as included silver sulfide mineral phases or as limited silver in solid solution within the galena structure. These argentiferous galenas have long been an important ore of silver.

.jpg.webp)

Galena deposits are found worldwide in various environments.[3] Noted deposits include those at Freiberg in Saxony;[1] Cornwall, the Mendips in Somerset, Derbyshire, and Cumberland in England; the Madan and Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria; the Sullivan Mine of British Columbia; Broken Hill and Mount Isa in Australia; and the ancient mines of Sardinia. In the United States, it occurs most notably in the Mississippi Valley type deposits of the Lead Belt in southeastern Missouri, which is the largest known deposit,[1] and in the Driftless Area of Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin.

Galena also was a major mineral of the zinc-lead mines of the tri-state district around Joplin in southwestern Missouri and the adjoining areas of Kansas and Oklahoma.[1] Galena is also an important ore mineral in the silver mining regions of Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Montana. Of the latter, the Coeur d'Alene district of northern Idaho was most prominent.[1]

The largest documented crystal of galena is composite cubo-octahedra from the Great Laxey Mine, Isle of Man, measuring 25 cm × 25 cm × 25 cm (10 in × 10 in × 10 in).[5]

Importance

Galena is the official state mineral of the U.S. states of Kansas, Missouri and Wisconsin; the former mining communities of Galena, Kansas, and Galena, Illinois, take their names from deposits of this mineral.

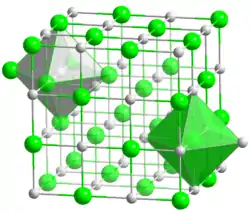

Crystal structure

Galena belongs to the octahedral sulfide group of minerals that have metal ions in octahedral positions, such as the iron sulfide pyrrhotite and the nickel arsenide niccolite. The galena group is named after its most common member, with other isometric members that include manganese bearing alabandite and niningerite.[3]

Divalent lead (Pb) cations and sulfur (S) anions form a close-packed cubic unit cell much like the mineral halite of the halide mineral group. Zinc, cadmium, iron, copper, antimony, arsenic, bismuth and selenium also occur in variable amounts in galena. Selenium substitutes for sulfur in the structure constituting a solid solution series. The lead telluride mineral altaite has the same crystal structure as galena.

Geochemistry

Within the weathering or oxidation zone galena alters to anglesite (lead sulfate) or cerussite (lead carbonate). Galena exposed to acid mine drainage can be oxidized to anglesite by naturally occurring bacteria and archaea, in a process similar to bioleaching.[6]

Uses of galena

One of the oldest uses of galena was in the eye cosmetic kohl. In Ancient Egypt, this was applied around the eyes to reduce the glare of the desert sun and to repel flies, which were a potential source of disease.[7]

In pre-Columbian North America, galena was used by indigenous peoples as an ingredient in decorative paints and cosmetics, and widely traded throughout the eastern United States.[8] Traces of galena are frequently found at the Mississippian city at Kincaid Mounds in present-day Illinois.[9] The galena used at the site originated from deposits in southeastern and central Missouri and the Upper Mississippi Valley.[8]

Galena is the primary ore of lead, and is often mined for its silver content, such as at the Galena Mine in northern Idaho.

It can be used as a source of lead in ceramic glaze.[10]

Galena is a semiconductor with a small band gap of about 0.4 eV, which found use in early wireless communication systems. It was used as the crystal in crystal radio receivers, in which it was used as a point-contact diode capable of rectifying alternating current to detect the radio signals. The galena crystal was used with a sharp wire, known as a "cat's whisker" in contact with it.[11]

See also

References

- Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (1990). "Galena". Handbook of Mineralogy (PDF). 1. Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209708.

- Galena. Webmineral

- Galena. Mindat.org

- Young, Courtney A.; Taylor, Patrick R.; Anderson, Corby G. (2008). Hydrometallurgy 2008: Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium. SME. ISBN 9780873352666.

- Rickwood, P. C. (1981). "The largest crystals" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 885–907.

- Da Silva, Gabriel (2004). "Kinetics and mechanism of the bacterial and ferric sulphate oxidation of galena". Hydrometallurgy. 75: 99. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2004.07.001.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (2005). The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York. p. 10. ISBN 1-58839-170-1.

- "Lead pollution from Native Americans attributed to crushing galena for glitter paint, adornments". Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- The Glittery Legacy of Lead at a Historic Native American Site, Atlas Obscura, November 7, 2019

- Glaze, http://www.thepotteries.org/types/glaze.htm.

- Lee, Thomas H. (2007). "The (Pre-)History of the Integrated Circuit: A Random Walk" (PDF). IEEE Solid-State Circuits Newsletter. 12 (2): 16–22. doi:10.1109/N-SSC.2007.4785573. ISSN 1098-4232.

Further reading

- Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S., Jr. (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (2nd ed.). Wiley. pp. 274–276. ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Galena. |