Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Pieter Bruegel (also Brueghel or Breughel) the Elder (/ˈbrɔɪɡəl/,[2][3][4] also US: /ˈbruːɡəl/;[5][6] Dutch: [ˈpitər ˈbrøːɣəl] (![]() listen); c. 1525–1530 – 9 September 1569) was the most significant artist of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, a painter and printmaker, known for his landscapes and peasant scenes (so-called genre painting); he was a pioneer in making both types of subject the focus in large paintings.

listen); c. 1525–1530 – 9 September 1569) was the most significant artist of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, a painter and printmaker, known for his landscapes and peasant scenes (so-called genre painting); he was a pioneer in making both types of subject the focus in large paintings.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Pieter Bruegel c. 1525–1530 |

| Died | 9 September 1569 (aged 39 to 44) |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking |

Notable work | The Hunters in the Snow, The Peasant Wedding, (composition of) Landscape with the Fall of Icarus |

| Movement | Dutch and Flemish Renaissance |

He was a formative influence on Dutch Golden Age painting and later painting in general in his innovative choices of subject matter, as one of the first generation of artists to grow up when religious subjects had ceased to be the natural subject matter of painting. He also painted no portraits, the other mainstay of Netherlandish art. After his training and travels to Italy, he returned in 1555 to settle in Antwerp, where he worked mainly as a prolific designer of prints for the leading publisher of the day. Only towards the end of the decade did he switch to make painting his main medium, and all his famous paintings come from the following period of little more than a decade before his early death, when he was probably in his early forties, and at the height of his powers.

As well as looking forwards, his art reinvigorates medieval subjects such as marginal drolleries of ordinary life in illuminated manuscripts, and the calendar scenes of agricultural labours set in landscape backgrounds, and puts these on a much larger scale than before, and in the expensive medium of oil painting. He does the same with the fantastic and anarchic world developed in Renaissance prints and book illustrations.[7]

He is sometimes referred to as "Peasant Bruegel", to distinguish him from the many later painters in his family, including his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1638). From 1559, he dropped the 'h' from his name and signed his paintings as Bruegel; his relatives continued to use "Brueghel" or "Breughel".

Life

Early life

The two main early sources for Bruegel's biography are Lodovico Guicciardini's account of the Low Countries (1567) and Karel van Mander's 1604 Schilder-boeck.[8] Guicciardini recorded that Bruegel was born in Breda, but Van Mander specified that Bruegel was born in a village (dorp) near Breda called "Brueghel",[9] which does not fit any known place.[10] Nothing at all is known of his family background. Van Mander seems to assume he came from a peasant background, in keeping with the over-emphasis on Bruegel's peasant genre scenes given by van Mander and many early art historians and critics.[11]

In contrast, scholars of the last sixty years have emphasized the intellectual content of his work, and conclude: "There is, in fact, every reason to think that Pieter Bruegel was a townsman and a highly educated one, on friendly terms with the humanists of his time",[12] ignoring Van Mander's dorp and just placing his childhood in Breda itself.[11] Breda was already a significant centre as the base of the House of Orange-Nassau, with a population of some 8,000,[13] although 90% of the 1300 houses were destroyed in a fire in 1534. However, this reversal can be taken to excess; although Bruegel moved in highly educated humanist circles, it seems "he had not mastered Latin", and had others add the Latin captions in some of his drawings.[14]

From the fact that Bruegel entered the Antwerp painters' guild in 1551, it is inferred that he was born between 1525 and 1530.[15] His master, according to Van Mander, was the Antwerp painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst.[16]

Between 1545 and 1550 he was a pupil of Pieter Coecke, who died on 6 December 1550.[17] However, before this, Bruegel was already working in Mechelen, where he is documented between September 1550 and October 1551 assisting Peeter Baltens on an altarpiece (now lost), painting the wings in grisaille.[12] Bruegel possibly got this work via the connections of Mayken Verhulst, the wife of Pieter Coecke. Mayken's father and eight siblings were all artists or married an artist, and lived in Mechelen.[18]

Travel

In 1551 Bruegel became a free master in the Guild of Saint Luke of Antwerp. He set off for Italy soon after, probably by way of France. He visited Rome and, rather adventurously for the period, by 1552 he had reached Reggio Calabria at the southern tip of the mainland, where a drawing records the city in flames after a Turkish raid.[19] He probably continued to Sicily, but by 1553 was back in Rome. There he met the miniaturist Giulio Clovio, whose will of 1578 lists paintings by Bruegel; in one case a joint work. These works, apparently landscapes, have not survived, but marginal miniatures in manuscripts by Clovio are attributed to Bruegel.[20]

He left Italy by 1554, and had reached Antwerp by 1555, when the set of prints to his designs known as the Large Landscapes were published by Hieronymus Cock, the most important print publisher of northern Europe. Bruegel's return route is uncertain, but much of the debate over it was made irrelevant in the 1980s when it was realized that the celebrated series of large drawings of mountain landscapes thought to have been made on the trip were not by Bruegel at all.[22] However, all the drawings from the trip that are considered authentic are of landscapes; unlike most other 16th-century artists visiting Rome he seems to have ignored both classical ruins and contemporary buildings.[23]

Antwerp and Brussels

From 1555 until 1563, Bruegel lived in Antwerp, then the publishing centre of northern Europe, mainly working as a designer of over forty prints for Cock, though his dated paintings begin in 1557.[24] With one exception, Bruegel did not work the plates himself, but produced a drawing which Cock's specialists worked from. He moved in the lively Humanist circles of the city, and his change of name (or at least its spelling) in 1559 can be seen as an attempt to Latinize it; at the same time he changed the script he signed in from the Gothic blackletter to Roman capitals.[12]

In 1563, he married Pieter Coecke van Aelst's daughter Mayken Coecke in Brussels, where he lived for the remainder of his short life. While Antwerp was the capital of Netherlandish commerce as well as the art market,[25] Brussels was the centre of government. Van Mander tells a story that his mother-in-law pushed for the move to distance him from his established servant girl mistress.[26] By now painting had become his main activity, and his most famous works come from these years. His paintings were much sought after, with patrons including wealthy Flemish collectors and Cardinal Granvelle, in effect the Habsburg chief minister, who was based in Mechelen. Bruegel had two sons, both well known as painters, and a daughter about whom nothing is known. These were Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1638) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625); he died too early to train either of them. He died in Brussels on 9 September 1569 and was buried in the Kapellekerk.[27]

Van Mander records that before he died he told his wife to burn some drawings, perhaps designs for prints, carrying inscriptions "which were too sharp or sarcastic...either out of remorse or for fear that she might come to harm or in some way be held responsible for them", which has led to much speculation that they were politically or doctrinally provocative, in a climate of sharp tension in both these areas.[12]

Historical background

Bruegel was born at a time of extensive change in Western Europe. Humanist ideals from the previous century influenced artists and scholars. Italy was at the end of its High Renaissance of arts and culture, when artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci painted their masterpieces. In 1517, about eight years before Bruegel's birth, Martin Luther created his Ninety-five Theses and began the Protestant Reformation in neighboring Germany. Reformation was accompanied by iconoclasm and widespread destruction of art, including in the Low Countries. The Catholic Church viewed Protestantism and its iconoclasm as a threat to the Church. The Council of Trent, which concluded in 1563, determined that religious art should be more focused on religious subject-matter and less on material things and decorative qualities.

At this time, the Low Countries were divided into Seventeen Provinces, some of which wanted separation from the Habsburg rule based in Spain. The Reformation meanwhile produced a number of Protestant denominations that gained followers in the Seventeen Provinces, influenced by the newly Lutheran German states to the east and the newly Anglican England to the west. The Habsburg monarchs of Spain attempted a policy of strict religious uniformity for the Catholic Church within their domains and enforced it with the Inquisition. Increasing religious antagonisms and riots, political manoeuvrings, and executions eventually resulted in the outbreak of Eighty Years' War.

In this atmosphere Bruegel reached the height of his career as a painter. Two years before his death, the Eighty Years' War began between the United Provinces and Spain. Although Bruegel did not live to see it, seven provinces became independent and formed the Dutch Republic, while the other ten remained under Habsburg control at the end of the war.[28]

Subjects

Peasants

Pieter Bruegel specialized in genre paintings populated by peasants, often with a landscape element, though he also painted religious works. Making the life and manners of peasants the main focus of a work was rare in painting in Bruegel's time, and he was a pioneer of the genre painting. Many of his peasant paintings fall into two groups terms of scale and composition, both of which were original and influential on later painting. His earlier style shows dozens of small figures, seen from a high viewpoint, and spread fairly evenly across the central picture space. The setting is typically an urban space surrounded by buildings, within which the figures have a "fundamentally disconnected manner of portrayal", with individuals or small groups engaged in their own distinct activity, while ignoring all the others.[29]

His earthy, unsentimental but vivid depiction of the rituals of village life—including agriculture, hunts, meals, festivals, dances, and games—are unique windows on a vanished folk culture, though still characteristic of Belgian life and culture today, and a prime source of iconographic evidence about both physical and social aspects of 16th-century life. For example, his famous painting Netherlandish Proverbs, originally The Blue Cloak, illustrates dozens of then-contemporary aphorisms, many of which still are in use in current Flemish, French, English and Dutch.[30] The Flemish environment provided a large artistic audience for proverb-filled paintings because proverbs were well known and recognizable as well as entertaining. Children's Games shows the variety of amusements enjoyed by young people. His winter landscapes of 1565, like The Hunters in the Snow, are taken as corroborative evidence of the severity of winters during the Little Ice Age. Bruegel often painted community events, as in The Peasant Wedding and The Fight Between Carnival and Lent. In paintings like The Peasant Wedding, Bruegel painted individual, identifiable people, while the people in The Fight Between Carnival and Lent are unidentifiable, muffin-faced allegories of greed or gluttony.

Bruegel also painted religious scenes in a wide Flemish landscape setting, as in the Conversion of Paul and The Sermon of St. John the Baptist. Even if Bruegel's subject matter was unconventional, the religious ideals and proverbs driving his paintings were typical of the Northern Renaissance. He accurately depicted people with disabilities, such as in The Blind Leading the Blind, which depicted a quote from the Bible: "If the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch" (Matthew 15:14). Using the Bible to interpret this painting, the six blind men are symbols of the blindness of mankind in pursuing earthly goals instead of focusing on Christ's teachings.

Using abundant spirit and comic power, Bruegel created some of the very early images of acute social protest in art history. Examples include paintings such as The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (a satire of the conflicts of the Protestant Reformation) and engravings like The Ass in the School and Strongboxes Battling Piggybanks.[31]

Over the 1560s, Bruegel moved to a style showing only a few large figures, typically in a landscape background without a distant view. His paintings dominated by their landscapes take a middle course as regards both the number and size of figures.

- Late monumental peasant figures

The Land of Cockaigne (1567), Alte Pinakothek, an illustration of the medieval mythical land of plenty called Cockaigne

The Land of Cockaigne (1567), Alte Pinakothek, an illustration of the medieval mythical land of plenty called Cockaigne The Peasant and the Nest Robber (1568), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The Peasant and the Nest Robber (1568), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna The Peasant Dance (1568), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, oil on oak panel

The Peasant Dance (1568), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, oil on oak panel The Beggars (The Cripples) (1568), Louvre, Paris, oil on panel

The Beggars (The Cripples) (1568), Louvre, Paris, oil on panel

Landscape elements

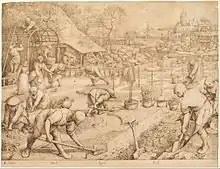

Bruegel adapted and made more natural the world landscape style, which shows small figures in an imaginary panoramic landscape seen from an elevated viewpoint that includes mountains and lowlands, water, and buildings. Back in Antwerp from Italy he was commissioned in the 1550s by the publisher Hieronymus Cock to make drawings for a series of engravings, the Large Landscapes, to meet what was now a growing demand for landscape images.

Some of his earlier paintings, such as his Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (Courtauld, 1563), are fully within the Patinir conventions, but his Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (known from two copies) had a Patinir-style landscape, in which already the largest figure was a genre figure who was only a bystander for the supposed narrative subject, and may not even be aware of it. The date of Bruegel's lost original is unclear,[32] but it is probably relatively early, and if so, foreshadows the trend of his later works. During the 1560s the early scenes crowded with multitudes of very small figures, whether peasant genre figures or figures in religious narratives, give way to a small number of much larger figures.

Months of the year

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

His famous set of landscapes with genre figures depicting the seasons are the culmination of his landscape style; the five surviving paintings use the basic elements of the world landscape (only one lacks craggy mountains) but transform them into his own style. They are larger than most previous works, with a genre scene with several figures in the foreground, and the panoramic view seen past or through trees.[33] Bruegel was also aware of the Danube School's landscape style through prints.[34]

The series on the months of the year includes several of Bruegel's best-known works. In 1565, a wealthy patron in Antwerp, Niclaes Jonghelinck, commissioned him to paint a series of paintings of each month of the year. There has been disagreement among art historians as to whether the series originally included six or twelve works.[35] Today, only five of these paintings survive and some of the months are paired to form a general season. Traditional Flemish luxury books of hours (e.g., the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry;[30] 1416) had calendar pages that included the Labours of the Months, depictions set in landscapes of the agricultural tasks, weather, and social life typical for that month.

Bruegel's paintings were on a far larger scale than a typical calendar page painting, each one approximately three feet by five feet. For Bruegel, this was a large commission (the size of a commission was based on how large the painting was) and an important one. In 1565, the Calvinist riots began and it was only two years before the Eighty Years' War broke out. Bruegel may have felt safer with a secular commission so as to not offend Calvinist or Catholic.[36] Some of the most famous paintings from this series included The Hunters in the Snow (December–January) and The Harvesters (August).

Prints and drawings

.jpg.webp)

On his return from Italy to Antwerp, Bruegel earned his living producing drawings to be turned into prints for the leading print publisher of the city, and indeed northern Europe, Hieronymus Cock. At his "House of the Four Winds" Cock ran a well-oiled production and distribution operation efficiently turning out prints of many sorts that was more concerned with sales than the finest artistic achievement. Most of Bruegel's prints come from this period, but he continued to produce drawn designs for prints until the end of his life, leaving only two completed out of a series of the Four Seasons.[37] The prints were popular and it is reasonable to assume that all those published have survived. In many cases we also have Bruegel's drawings. Although the subject matter of his graphic work was often continued in his paintings, there are considerable differences in emphases between the two oeuvres. To his contemporaries and for long after, until public museums and good reproductions of the paintings made these better known, Bruegel was much better known through his prints than his paintings, which largely explains the critical assessment of him as merely the creator of comic peasant scenes.[38]

The prints are mostly engravings, though from about 1559 onwards some are etchings or mixtures of both techniques.[39] Only one complete woodcut was made from a Bruegel design, with another left incomplete. This, The Dirty Wife, is a most unusual survival (now Metropolitan Museum of Art) of a drawing on the wooden block intended for printing. For some reason, the specialist block-cutter who carved away the block, following the drawing while also destroying it, had only done one corner of the design before stopping work. The design then appears as an engraving, perhaps soon after Bruegel's death.[40]

Among his greatest successes were a series of allegories, among several designs adopting many of the very individual mannerisms of his compatriot Hieronymus Bosch: The Seven Deadly Sins and The Virtues. The sinners are grotesque and unidentifiable while the allegories of virtue often wear odd headgear.[36] That imitations of Bosch sold well is demonstrated by his drawing Big Fish Eat Little Fish (now Albertina), which Bruegel signed but Cock shamelessly attributed to Bosch in the print version.[21]

Although Bruegel presumably made them, no drawings that are clearly preparatory studies for paintings survive. Most surviving drawings are finished designs for prints, or landscape drawings that are fairly finished. After a considerable purge of attributions in recent decades, led by Hans Mielke,[12] sixty-one sheets of drawings are now generally agreed to be by Bruegel.[41] A new "Master of the Mountain Landscapes" has emerged from the carnage. Mielke's key observation was that the lily watermark on the paper of several sheets was only found from around 1580 onwards, which led to the rapid acceptance of his proposal.[42] Another group of about twenty-five pen drawings of landscapes, many signed and dated as by Bruegel, are now given to Jacob Savery, probably from the decade of so before Savery's death in 1603. A giveaway was that two drawings including the walls of Amsterdam were dated 1563 but included elements only built in the 1590s. This group appears to have been made as deliberate forgeries.[43]

Family

Around 1563 Bruegel moved from Antwerp to Brussels, where he married Mayken Coecke, the daughter of the painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Mayken Verhulst. As registered in the archives of the Cathedral of Antwerp, their deposition for marriage was registered 25 July 1563. The marriage itself was concluded in the Chapel Church, Brussels in 1563.[44][45]

Pieter the Elder had two sons: Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Jan Brueghel the Elder (both kept their name as Brueghel). Their grandmother, Mayken Verhulst, trained the sons because "the Elder" died when both were very small children. The older brother, Pieter Brueghel copied his father's style and compositions with competence and considerable commercial success. Jan was much more original, and very versatile. He was an important figure in the transition to the Baroque style in Flemish Baroque painting and Dutch Golden Age painting in a number of its genres. He was often a collaborator with other leading artists, including with Peter Paul Rubens on many works including the Allegory of Sight.

Other members of the family include Jan van Kessel the Elder (grandson of Jan Bruegel the Elder) and Jan van Kessel the Younger. Through David Teniers, the family is also related to the whole Teniers family of painters and the Quellinus family of painters and sculptors, since Jan-Erasmus Quellinus married Cornelia, daughter of David Teniers the Younger.

Reception history

Bruegel's art was long more highly valued by collectors than critics. His friend Abraham Ortelius described him in a friendship album in 1574 as "the most perfect painter of his century", but both Vasari and Van Mander see him as essentially a comic successor to Hieronymus Bosch.[46]

But Bruegel's work was, as far as we know, always keenly collected. The banker Nicolaes Jonghelinck owned sixteen paintings; his brother Jacques Jonghelinck was a gentleman-sculptor and medallist, who also had significant business interests. He made medals and tombs in an international style for the Brussels elite, especially Cardinal Granvelle, who was also a keen patron of Bruegel.[47] Granvelle owned at least two Bruegels, including the Courtauld Flight into Egypt, but we do not know if he bought them directly from the artist.[48] Granvelle's nephew and heir was strong-armed out of his Bruegels by Rudolf II, the very acquisitive Austrian Habsburg Emperor. The series of the Months entered the Habsburg collections in 1594, given to Rudolf's brother and later taken by the emperor himself. Rudolf eventually owned at least ten Bruegel paintings.[49] A generation later Rubens owned eleven or twelve, which mostly passed to the Antwerp senator Pieter Stevens, and were then sold in 1668.[50]

Bruegel's son Pieter could still keep himself and a large studio team busy producing replicas or adaptations of Bruegel's works, as well as his own compositions along similar lines, sixty years or more after they were first painted. The most frequently copied works were generally not the ones that are most famous today, though this may reflect the availability of the full-scale detailed drawings that were evidently used. The most-copied painting is the Winter Landscape with (Skaters and) a Bird Trap (1565), of which the original is in Brussels; 127 copies are recorded.[52] They include paintings after some of Bruegel's drawn print designs, especially Spring.[53]

The next century's artists of peasant genre scenes were heavily influenced by Brueghel.[53] Outside the Brueghel family, early figures were Adriaen Brouwer (c. 1605/6-1638) and David Vinckboons (1576–c.1632), both Flemish-born but spending much of their time in the northern Netherlands. As well as the general conception of such kermis subjects, Vinckboons and other artists took from Bruegel "such stylistic devices as the bird's-eye perspective, ornamentalized vegetation, bright palette, and stocky, odious figures.[54] Forty years after their deaths, and over a century after Bruegel's, Jan Steen (1626–79) continued to show a particular interest in Bruegelian treatments.[29]

The critical treatment of Bruegel as essentially an artist of comic peasant scenes persisted until the late 19th century, even after his best paintings became widely visible as royal and aristocratic collections were turned into museums. This had been partly explicable when his work was mainly known from copies, prints and reproductions.[12] Even Henri Hymans, whose work of 1890/91 was the first important contribution to modern Bruegel scholarship, could describe him thus: "His field of enquiry is certainly not of the most extensive; his ambition, too, is modest. He confines himself to a knowledge of mankind and the most immediate objects", a line no modern scholar is likely to take.[12] As his landscape paintings, in good colour reproduction, have become his best-loved works, so his importance in the history of landscape art has become understood.[12]

Works

There are about forty generally accepted surviving paintings, twelve of which are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.[55] A number of others are known to have been lost, including what, according to van Mander, Bruegel himself thought his best work, "a picture in which Truth triumphs".[56]

Bruegel only etched one plate himself, The Rabbit Hunt, but designed some forty prints, both engravings and etchings, mostly for the Cock publishing house. As discussed above, about sixty-one drawings are now recognized as authentic, mostly designs for prints or landscapes.

A Pig Has To Go in a Sty, 1557, Bruegel's earliest genre scene

A Pig Has To Go in a Sty, 1557, Bruegel's earliest genre scene

The Wedding Dance (c.1566), oil on oak panel, The Detroit Institute of Arts

The Wedding Dance (c.1566), oil on oak panel, The Detroit Institute of Arts The Census at Bethlehem (1566), oil on wood panel, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

The Census at Bethlehem (1566), oil on wood panel, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

Selected works

- Landscape with Christ and the Apostles at the Sea of Tiberias, 1553, probably with Maarten de Vos, private collection

- Parable of the Sower, 1557, Timken Museum of Art, San Diego

- Twelve Proverbs, 1558, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

- Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, probably 1550s, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels – Note: Now seen as a copy of a lost authentic Bruegel painting[57]

- The Blue Cloak (or Flemish Proverbs), 1559, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, 1559, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Portrait of an Old Woman, 1560, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Temperance, 1560

- Children's Games, 1560, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Naval Battle in the Gulf of Naples, 1560, Galleria Doria-Pamphilj, Rome

- The Fall of the Rebel Angels 1562, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

- The Suicide of Saul (Battle Against The Philistines on the Gilboa), 1562, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Two Monkeys, 1562, Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- The Triumph of Death, c. 1562, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Dulle Griet (Mad Meg), c. 1563, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

- The "Large" Tower of Babel, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The "Little" Tower of Babel, c. 1563, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

- Landscape with the Flight into Egypt, 1563, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London

- The Death of the Virgin, 1564, (grisaille), Upton House, Banbury

- The Procession to Calvary, 1564, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Adoration of the Kings, 1564, The National Gallery, London

.JPG.webp)

- Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap, 1565, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, inv. 8724

- The Months, a cycle of probably six paintings of the months or seasons, of which five remain:

- The Hunters in the Snow (Dec.–Jan.), 1565, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Gloomy Day (Feb.–Mar.), 1565, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Hay Harvest (June–July), 1565, Lobkowicz Palace at the Prague Castle Complex, Czech Republic

- The Harvesters (Aug.-Sept.), 1565, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- The Return of the Herd (Oct.–Nov.), 1565, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1565), Courtauld Institute of Art, London

- Preaching of John the Baptist, 1566, Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest)

- The Census at Bethlehem, 1566, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

- The Wedding Dance, c. 1566, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

- Conversion of Paul, 1567, Kunsthistorishes Museum, Vienna

- Massacre of the Innocents, c. 1567, versions at Royal Collection, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, at Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu,[59] and at Upton House, Banbury

- The Land of Cockaigne, 1567, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow, 1567, Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur

- The Magpie on the Gallows, 1568, Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt

- The Misanthrope, 1568, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

- The Blind Leading the Blind, 1568, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

- The Peasant Wedding, 1568, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Peasant Dance, 1568, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Beggars (The Cripples), 1568, Louvre, Paris

- The Peasant and the Nest Robber, 1568, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Three Soldiers, 1568, The Frick Collection, New York City

- The Storm at Sea, an unfinished work, probably Bruegel's last painting.

- The Wine of Saint Martin's Day, Museo del Prado, Madrid (discovered in 2010)

Village views with trees and a mule, 1526–1569, The Phoebus Foundation

Village views with trees and a mule, 1526–1569, The Phoebus Foundation

- Prints and drawings

- Large Fish Eat Small Fish, 1556; we have both Bruegel's design and prints after it

- Ass at School, 1556, drawing, Print room, Berlin State Museums

- The Calumny of Apelles, 1565, drawing, British Museum, London

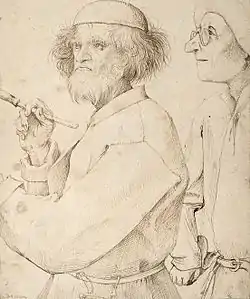

- The Painter and the Connoisseur, drawing, c. 1565, Albertina, Vienna

- Village views with trees and a mule, 1526–1569, The Phoebus Foundation

Work referenced in others' work

His painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, now thought only to survive in copies, is the subject of the 1938 poem "Musée des Beaux Arts" by W. H. Auden:

In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

It also was the subject of a 1960 poem by William Carlos Williams and was referenced in Nicolas Roeg's 1976 science fiction film The Man Who Fell to Earth. Further, Williams' final collection of poetry references a number of Bruegel's work.

Bruegel's painting Two Monkeys was the subject of Wisława Szymborska's 1957 poem, "Brueghel's Two Monkeys".[60]

Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky referenced Bruegel's paintings in his films several times, notably in Solaris (1972) and The Mirror (1975).

Director Lars von Trier also uses Bruegel's paintings in his film Melancholia (2011). This was used as a reference to Tarkovsky's Solaris, a movie with related themes.

His 1564 painting The Procession to Calvary inspired the 2011 Polish-Swedish film co-production The Mill and the Cross, in which Bruegel is played by Rutger Hauer. Bruegel's paintings in the Kunsthistorisches Museum are shown in the 2012 film, Museum Hours, where his work is discussed at length by a guide.

Seamus Heaney referenced Brueghel in his poem "The Seed Cutters".[61] David Jones references the painting The Blind Leading the Blind in his World War One prose-poem In Parenthesis: "the stumbling dark of the blind, that Breughel knew about - ditch circumscribed".

Michael Frayn, in his novel Headlong, imagines a lost panel from the 1565 Months series resurfacing unrecognized, which triggers a mad conflict between an art (and money) lover and the boor who possesses it. Much thought is spent on Bruegel's secret motives for painting it.

In his book American Barricade, Danniel Schoonebeek references several Brueghel paintings in his poem "Poem for a Seven-Hour Flight", notably in the lines: "I am the hounds in Brueghel / do you know the hounds // here is the single fox I have killed will you wear it around your shoulders are you ashamed."

Author Don Delillo references Bruegel's painting The Triumph of Death in his novel Underworld and his short story "Pafko at the Wall". It is believed that the painting The Hunters in the Snow influenced the classic short story with the same title written by Tobias Wolff and featured in In the Garden of the North American Martyrs.

In the foreword to his novel The Folly of the World, author Jesse Bullington explains that Bruegel's painting Netherlandish Proverbs not only inspired the title but also the plot to some extent. Various sections are introduced with a proverb depicted in the painting that alludes to a plot element.

Poet Sylvia Plath references Bruegel's painting The Triumph of Death in her poem "Two Views of a Cadaver Room" from her collection 'The Colossus and Other Poems.

See also

Notes

- Orenstein, 63–64

- "Bruegel". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia.

- "Brueghel". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Bruegel". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Brueghel". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Brueghel". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Gombrich, 295; Clark, 41–43, 27, 33, 57, also covering Gothic aspects of Bruegel's style

- Grove; van Mander's Bruegel biography in Dutch; Wied, 15–18 gives a full English translation. Guicciardini was an Italian who had lived in Antwerp since at least 1542, and probably knew Bruegel, which Van Mander, born in 1648 on the other side of Flanders, is most unlikely to have done.

- "den welcken is geboren niet wijt van Breda, op een Dorp geheeten Brueghel, welcks naem hy met hem ghedraghen heeft, en zijn naecomelinghen ghelaten."

- Grove: "none of the three Flemish villages of that name is close to Breda".; Wied, 18, says two of the villages (Groot Bruegel and Cleyn Bruegel) are close to Bree, Belgium, which is "Breda" in Latin, perhaps causing Van Mander confusion. Son en Breugel still has supporters but is 34 miles from Breda, though just outside Eindhoven – see RKD.

- Orenstein, 57–58; Grove

- Grove

- Wied, 19–20

- Orenstein, 64

- Orenstein, 5; Grove

- Orenstein, 5

- This is according to Van Mander; although there is no documentation and little evident stylistic influence from his future father-in-law, modern scholars generally accept this.

- Orenstein, 5, 7

- Grove; Orenstein, 204 for the drawing

- Orenstein, 5–6; Grove

- Orenstein, 140–142

- Orenstein, 266–267, and following catalogue pages; Grove

- Snyder, 502; Orenstein, 96–97 for one agreed exception; see this British Museum page for another drawing of Roman ruins, perhaps the Colosseum, recently attributed to Bruegel

- Orenstein, 7

- Wied, 9–10

- Van Mander, quoted in Wied, 16; Orenstein, 7; Hagens, 15

- Grove; Orenstein, 8–9

- Foote, Timothy (1968). The World of Bruegel. Library of Congress: Time-Life Library of Art. pp. 18–27.

- Franits, 203

- Stokstad, Cothren, Marilyn, Michael (2010). Art History- Fourteenth to Seventeenth Century Art.

- Mayor, A. Hyatt (1971). Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 426.

- about 1558 has been suggested

- Silver, 39–52; Snyder, 502–510; Harbison, 140–142; Schama, 431–433

- Wood, Chapter 5, especially 275–278

- Gibson, Walter S. (1977) :) . Bruegel. The World of Art Library. Thames and Hudson pp 147–148.

- Foote, Timothy (1968). The World of Bruegel. Library of Congress: Time-Life Library.

- Orenstein, 236–238, and following pages

- Wied, 36

- Orenstein catalogues the prints in chronological order, as far as it is known

- Orenstein, 241–242, 246–248; Metropolitan page

- Orenstein, vii gives the total; fifty-four were in the exhibition and are catalogued, and most others illustrated. These included all those from the largest collections, Berlin (10), London (8) and Vienna (6). Sellink in 2012 lists 70.

- Orenstein, 266–267, and following catalogue pages for individual works.

- Orenstein, 276–277, and following catalogue pages for individual works.

- Jean Bastiaensen, “De verloving van Pieter Bruegel de Oude. Nieuw licht op de Antwerpse verankering”, Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen, 51 (2013), no. 1: 26–27.

- "Pieter Bruegel, the Elder | Flemish artist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Snyder, 484; Orenstein, 9-11, 59

- Snyder, 484–485

- Orenstein, 9–10; p. 30

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh; Princes and Artists, Patronage and Ideology at Four Habsburg Courts 1517–1633, 116, 1976, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500232326

- Braham, Helen, The Princes Gate Collection, p. 7, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1981, ISBN 0904563049

- Wied, 144, 186

- Sotheby's: Catalogue note on a good copy, sold London, Lot 10 9 July 2014

- Orenstein, 67–84

- Franits, 35, 53–54

- Grove; Manfred Sellink in 2012 listed forty paintings, seventy drawings and seventy-five prints, the latter slightly higher numbers than other sources.

- Wied, 17

- (Het journaal 1–11/11/09). "deredactie.be". Vrtnieuws.net. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- "Lobkowicz Fundraiser". Lobkowicz Fundraiser. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "Muzeul National Brukenthal Sibiu". www.brukenthalmuseum.ro. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Szymborska, Wislawa (1995). View With a Grain of Sand. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 3.

- Heaney, Seamus (22 December 2010). Opened Ground: Poems 1966–1996. Faber & Faber. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-571-26279-3.

References

- Clark, Kenneth, Landscape into Art, 1949, page refs to Penguin edn of 1961

- Franits, Wayne, Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting, Yale UP, 2004, ISBN 0300102372

- Gombrich, E.H., The Story of Art, Phaidon, 13th edn. 1982. ISBN 0 7148 1841 0

- "Grove": Wied, Alexander and Van Miegroet, Hans J. "Bruegel." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 2 February 2017, subscription required

- Harbison, Craig. The Art of the Northern Renaissance, 1995, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0297835122

- "Hagens": Hagen, Rose-Marie; Hagen, Rainer, Bruegel, The Complete Paintings, 2001, Midpoint Press, ISBN 3822815314

- Hugh Honour and John Fleming, A World History of Art, 1st edn. 1982 (many later editions), Macmillan, London, page refs to 1984 Macmillan 1st edn. paperback. ISBN 0333371852

- Orenstein, Nadine M., ed. (2001). Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-990-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) fully online

- Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, 1995, HarperCollins (2004 HarperPerennial edn used), ISBN 0006863485

- Silver, Larry, Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: The Rise of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market, 2006, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0812222113, 9780812222111, Google Books

- Snyder, James. Northern Renaissance Art, 1985, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0136235964

- Wied, Alexander, Bruegel, 1980, Studio Vista, ISBN 0289709741

- Wood, Christopher, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, 1993, Reaktion Books, London, ISBN 0948462469

Further reading

- Silver, Larry, Pieter Bruegel, 2011

- Joseph Leo Koerner, Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts), 2016, Princeton

- Jos Koldeweij; Matthijs Ilsink, Hieronymus Bosch: Visions of Genius, 2016, Yale

- Sellink, Manfred, Bruegel: The Complete Paintings, Drawings and Prints, 2007

- Meganck, Tine Luk Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Fall of the Rebel Angels: Art, Knowledge and Politics on the Eve of the Dutch Revolt, 2014, Milan, Silvana Editoriale

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pieter Bruegel (I). |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Breughel, Pieter. |

- Pieter-Bruegel-The-Elder.org: 99 works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder in BALaT — Belgian Art Links and Tools (KIK-IRPA, Brussels).

- Pubhist.com: Gallery of all paintings and drawings

- Academia.edu: The political consciousness of Pieter Bruegel

- Bruegel blockbuster in Vienna – largest ever exhibition on Bruegel in 2018