Sam Gilliam

Sam Gilliam (/ˈɡɪliəm/ GHIL-ee-əm; born November 30, 1933)[1] is an African-American color field painter and lyrical abstractionist artist. Gilliam is associated with the Washington Color School,[2] a group of Washington, D.C. area artists that developed a form of abstract art from color field painting in the 1950s and 1960s. His works have also been described as belonging to abstract expressionism and lyrical abstraction.[3] He works on stretched, draped and wrapped canvas, and adds sculptural 3D elements. He is recognized as the first artist to introduce the idea of a draped, painted canvas hanging without stretcher bars around 1965. This was a major contribution to the Color Field School.[4]

Sam Gilliam | |

|---|---|

Sam Gilliam speaking at AU Katzen Arts Center, 2018 | |

| Born | November 30, 1933 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Louisville |

| Movement | Washington Color School |

| Children | Leah Gilliam |

In his more recent work, Gilliam has worked with polypropylene, computer-generated imaging, metallic and iridescent acrylics, handmade paper, aluminum, steel, plywood, and plastic.[5]

Biography

Sam Gilliam was born in Tupelo, Mississippi,[1] the seventh of eight children born to Sam and Estery Gilliam.[6] The Gilliams moved to Louisville, Kentucky[1] shortly after he was born. His father worked on the railroad; his mother cared for the large family. At a young age, Gilliam wanted to be a cartoonist and spent most of his time drawing.[7] In 1951, Gilliam graduated from Central High School in Louisville. After high school, Gilliam attended the University of Louisville[1] and received his B.A. degree in Fine Arts in 1955 as a member of the second admitted class of black undergraduate students.[8] In the same year he held his first solo art exhibition at the University. From 1956 to 1958 Gilliam served in the United States Army.[1] He returned to the University of Louisville in 1961 and, as a student of Charles Crodel,[9] received his M.A. degree in painting.[10]Gilliam listened to his college professor's advice to become a high school teacher and was able to teach art at Washington's McKinley High School.[11][12] Gilliam devoted on developing his painting during his weekdays reserved for the classroom.[13]In 1962, Gilliam moved to Washington, D.C. after marrying Washington Post reporter Dorothy Butler[14]who is also the first African American female reporter at the Washington Post[15]Gilliam currently lives in Washington, D.C. with his long-term partner Annie Gawlak.[7]

Career in the 1960s, early 1970s

In the 1960s, as the political and social front of America began to explode in all directions, Gilliam began to take bold declarative initiatives, making definitive imagery[16], inspired by the specific conditions of the African-American experience. This was at a time that "abstract art was said by some to be irrelevant to black African life."[17] Abstraction remained a critical issue for artists such as Gilliam. His early style developed from brooding figural abstractions into large paintings of flatly applied color, pushing Gilliam to eventually remove the easel by eliminating the stretcher. During this time period, Gilliam painted large color-stained canvases, which he draped and suspended from the walls and ceilings, comprising some of his best-known artwork.[18][19]

In 1972, Gilliam represented the US at the Venice Biennale, the first African-American artist to do so.[6][19] In 2017, he exhibited at the Venice Biennale once again, in the Giardini's central pavilion.[20]

Gilliam was influenced by German Expressionists such as Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, and the American Bay Area Figurative School artist Nathan Oliveira. Early influences included Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. He says that he found many clues about how to go about his work from Tatlin, Frank Stella, Hans Hofmann, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Cézanne. In 1963, Thomas Downing, an artist who identified himself with the Washington Color School, introduced Gilliam to this new school of thought. Around 1965, Gilliam became the first painter to introduce the idea of the unsupported canvas. He was inspired to do this by observing laundry hanging outside his Washington studio.[6] His drape paintings were suspended from ceilings or arranged on walls or floors, representing a sculptural third dimension in painting. Gilliam says that his paintings are based on the fact that the framework of the painting is in real space. He is attracted to its power and the way it functions. Gilliam's draped canvases change in each environment where they are arranged and frequently he embellishes the works with metal, rocks, and wooden beams.[21]

Career in the 1970s and 1980s

In 1975, Gilliam veered away from the draped canvases, and became influenced by jazz musicians such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane.[22] He started producing dynamic geometric collages, which he called "Black Paintings" because they are painted in shades of black.[14] In the 1980s Gilliam's style changed dramatically once more, transitioning to quilted paintings reminiscent of African patchwork quilts from his childhood, using an improvisational approach.[23]

His most recent works are textured paintings that incorporate metal forms.

Recognition

Gilliam has had many commissions, grants, awards, exhibitions and honorary doctorates. A major retrospective of his work was held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 2005.[24] He was named the 2006 University of Louisville Alumnus of the Year.[25]

Other honors include eight honorary doctorates, and the Kentucky Governor's Award in the Arts. He has received several National Endowment for the Arts grants, the Longview Foundation Award, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He also received the Art Institute of Chicago's Norman W. Harris Prize, and an Artist's Fellowship from the Washington Gallery of Modern Art.[25]

In 1987 he was selected by the Smithsonian Art Collectors Program to produce a print to celebrate the opening of the S. Dillon Ripley Center in the National Mall. He donated his talent to produce In Celebration, a 35-color limited-edition serigraph that highlighted his trademark use of color. The sale benefited the Smithsonian Associates, the continuing education branch of the larger Smithsonian Institution.[26] In early 2009, he again donated his talents to the Smithsonian Associates to produce a 90-color serigraph entitled Museum Moment, which he describes as "a celebration of art".[27]

In April 2003, a dedication of the installation of his work, Matrix Red-Matrix Blue, was held at Rutgers Law School, Newark.[28] In May 2011, his work From a Model to a Rainbow was installed in the Washington Metro Underpass at 4th and Cedar, NW.[29]

In 2016, Gilliam was commissioned to produce a piece as part of the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).[30] Sam Gilliam participated in the 2017 Venice Biennale, Viva Arte Viva, May 13–November 16, 2017.[31] In 2018, his work was exhibited at Art|Basel.[32] An exhibition at Dia:Beacon took place in August 2019,[33][34] where his work was described by The Wall Street Journal as "innovative, loosely draped work is a light and luminous addition to the galleries at Dia Beacon."[34]

The first major retrospective of his work in nearly two decades was announced and scheduled to open in 2022 at The Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC.[35]

Selected artwork

Solar Canopy, 1986[36]

An aluminum sculpture made by color field artist Sam Gilliam in 1986. It is a large 34'x 12'x 6" feet painted sculpture located at York College, City University of New York's Academic Core Lounge on the third floor across a huge open window. It is suspended from the ceiling at 60 ft (18 m) high. The artwork is made up of painted geometric shapes with many vibrant colors, some having a solid color while others have a tie-dye effect painted on them. The artwork is connected together in a horizontal diagonal with a circular shape in the middle. The circular middle is red on the outside and underneath is painted with many different colors in a tie-dye effect. It also has small blocks under it painted in solid colors of red, orange, blue and yellow. Attached to some of the small blocks are triangular blocks.

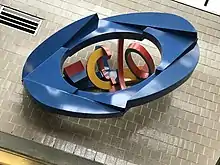

Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue, 1991

Located at the Jamaica Center train station (E,J,Z) is a large aluminum sculpture mounted high outside on a wall above one of the entrances.[37] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority Arts for Transit project commissioned the work in 1991. It is made up of geometric shapes painted in solid primary colors (red, yellow, blue). The shape of the overall sculpture is circular, with the outer part being blue while the inner parts are red and yellow. In the artist's words, the work "calls to mind movement, circuits, speed, technology, and passenger ships...the colors used in the piece... refer to colors of the respective subway lines. The predominant use of blue provides one with a visual solid in a transitional area that is near subterranean."[38]

Personal life

In 1962, Gilliam married Dorothy Butler, a Louisville native and the first African-American female columnist at The Washington Post. They divorced in the 1980s but have three daughters (Stephanie, Melissa, and Leah) and also have three grandchildren. After the divorce he met Annie Gawlak, owner of the G Fine Art gallery in Washington DC, who is now Gilliam's longtime partner.[39] In the 1960s, Gilliam was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed lithium, which badly damaged his kidneys. He stopped taking the medication and changed his diet by cutting out red meats and eating fruits and nuts. Gilliam lives in Washington D.C. but in 2010 sold his studio on 14th Street, NW, just north of Colorado Avenue for $3.85 million.

Selected museum collections

Gilliam's work is part of the permanent collections of 56 museums including:[25]

- Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL[25]

- Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA

- Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH

- Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[25]

- Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX[40]

- Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[25]

- Kreeger Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

- Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art, Shawnee, Okla.

- Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY[25]

- Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI

- Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

- Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France[41]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX[42]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY[25]

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[25][43]

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA

- Perez Art Museum Miami, Miami, FL

- The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

- Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Rose Art Museum, Waltham, MA[40]

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.[44]

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

- Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY

- The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY

- Tate Modern, London, England[45]

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

- Whitney Museum, New York, NY[25]

References

- "Sam Gilliam - Bio". www.phillipscollection.org. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- Cohen, Jean Lawlor; Cohen, Jean Lawlor (2015-06-26). "When the Washington Color School earned its stripes on the national stage". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- "Washington Color School Movement Overview". The Art Story. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "Colorscope: Abstract Painting 1960-1979". Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- "Sam Gilliam - Google Arts & Culture". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- Kinsella, Eileen (2 January 2018). "At Age 84, Living Legend Sam Gilliam Is Enjoying His Greatest Renaissance Yet". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Beer with a Painter: Sam Gilliam". Hyperallergic. 2016-03-19. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- Brown, Jackson (2017). "Sam Gilliam". Callaloo. 40 (5): 59–68. doi:10.1353/cal.2017.0155. ISSN 1080-6512. S2CID 201765406.

- https://www.leoweekly.com/2006/06/man-of-constant-color-sam-gilliama%C2%A2a%C2%ACa%C2%A2s-abstract-art-comes-home-for-a-retrospective/

- Sam Gilliam Jr., A Study of Different Uses of Solid Forms in Painting, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Louisville, 1961.

- Brown, Jackson (2017). "Sam Gilliam". Callaloo. 40 (5): 59–68. doi:10.1353/cal.2017.0155. ISSN 1080-6512. S2CID 201765406.

- "Sam Gilliam - Biography". rogallery.com. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- Brown, Jackson (2017). "Sam Gilliam". Callaloo. 40 (5): 59–68. doi:10.1353/cal.2017.0155. ISSN 1080-6512. S2CID 201765406.

- "Sam Gilliam". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- Brown, Jackson (2017). "Sam Gilliam". Callaloo. 40 (5): 59–68. doi:10.1353/cal.2017.0155. ISSN 1080-6512. S2CID 201765406.

- "Sam Gilliam (b.1932)". The Melvin Holmes Collection of African American Art. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Russell, John (1983). "Art". The New York Times.

- "Sam Gilliam facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Sam Gilliam". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- "Basking in Sam Gilliam's Endless Iterations". Hyperallergic. 2019-11-29. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- Campbell, Andrianna (July 11, 2017). "Sam Gilliam". Artforum International. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Tate. "'Simmering', Sam Gilliam, 1970 | Tate". Tate. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- "Sam Gilliam - Biography". rogallery.com. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Beardsley, John (1989). Sam Gilliam: Recent Paintings November 15 - December 16, 1989. Ingalls Library clipping file, The Cleveland Museum of Art: Barbara Fendrick Gallery. pp. n.p. (exhibition booklet without pages).

- Binstock, Jonathan P. (5 December 2005). Sam Gilliam : a retrospective catalogue. ISBN 9780520246348. OCLC 835849576.

- "Sam Gilliam". louisville.edu. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "In Celebration, 1987 by Sam Gilliam". The Smithsonian Associates. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Museum Moment, 2009 by Sam Gilliam". The Smithsonian Associates. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Rutgers Law School News" (PDF). Rutgers Law School. 2003-04-01. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- "Norton to Recognize World Renowned Artist Sam Gilliam During Metro Dedication Ceremony, Saturday". Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton. 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- Sargent, Antwaun (2016-09-22). "The Smithsonian's New African-American Museum Gives a Powerful Portrait of Black Experience". Artsy. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- "La Biennale di Venezia - Artists". www.labiennale.org. Archived from the original on 2017-06-29. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- Basel, Art. "Sam Gilliam: A life beyond the frame | Art Basel". Art Basel. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- "Sam Gilliam | Exhibitions & Projects | Exhibitions | Dia". www.diaart.org. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- Panero, James (2020-08-19). "'Sam Gilliam' Review: Flowing Color, Billowing Canvas". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- "A Major Sam Gilliam Retrospective Is Coming to the Hirshhorn | Washingtonian (DC)". Washingtonian. 2020-02-07. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- "Sam Gilliam, Solar Canopy, 1986", Unforgotten Masterpieces.

- "CultureNOW - Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue: Sam Gilliam and MTA Arts & Design". culturenow.org. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- "Jamaica Center-Parsons-Archer | Sam Gilliam", MTA Arts & Design, MTA.

- Capps, Kriston (March 27, 2015). "Return to Splendor". Washington City Paper. Washington DC. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- "At Age 84, Living Legend Sam Gilliam Is Enjoying His Greatest Renaissance Yet". artnet.com. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "Collections en ligne". Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "Search the Collection". MFAH. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "Collection search results: Gilliam, Sam". National Gallery of Art, Collection. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "Sam Gilliam - Works by This Artist". SAAM. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- Tate. "Sam Gilliam born 1933". Tate. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

Bibliography

- Sam Gilliam: a retrospective, October 15, 2005 to January 22, 2006, Corcoran Gallery of Art

- Binstock, Jonathan P., and Sam Gilliam. 2005. Sam Gilliam: a retrospective. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sam Gilliam papers, 1958–1989, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- AskArt lists 52 references to Sam Gilliam

- Washington Art, catalog of exhibitions at State University College at Potsdam, NY & State University of New York at Albany, 1971, Introduction by Renato G. Danese, printed by Regal Art Press, Troy NY.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sam Gilliam. |

- Sam Gilliam Papers, 1957-1989. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- "Sam Gilliam" files, Thelma & Bert Ollie Memorial Collection of Abstract Art by Black Artists: Files for Research and Education, Museum Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum

- Gilliam's Newest Work Inspires Dickstein Shapiro, Washingtonian magazine

- Sam Gilliam at the National Gallery of Art

- Sam Gilliam Lecture, March 9, 1977, from Maryland Institute College of Art's Decker Library, Internet Archive

- Sam Gilliam at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN