Sandy River (Oregon)

The Sandy River is a 56-mile (90 km) tributary of the Columbia River in northwestern Oregon in the United States. The Sandy joins the Columbia about 14 miles (23 km) upstream of Portland.

| Sandy River | |

|---|---|

Sandy River and Mount Hood | |

Location of the mouth of the Sandy River in Oregon | |

| Etymology | Named Quicksand River in 1805 by Lewis and Clark because of "emence quantitys of sand" at the mouth; apparently shortened to Sandy River locally by 1845–50[1] |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Clackamas County, Multnomah County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Mount Hood |

| • location | Clackamas County, Oregon |

| • coordinates | 45°22′32″N 121°43′45″W[2] |

| • elevation | 5,225 ft (1,593 m)[3] |

| Mouth | Columbia River |

• location | near Troutdale, Multnomah County, Oregon |

• coordinates | 45°34′05″N 122°24′03″W[2] |

• elevation | 10 ft (3.0 m)[2] |

| Length | 57 mi (92 km)[4] |

| Basin size | 508 sq mi (1,320 km2)[5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Dodge Park, 18.4 miles (29.6 km) from mouth[6][7] |

| • average | 2,300 cu ft/s (65 m3/s)[6][7] |

| • minimum | 45 cu ft/s (1.3 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 84,400 cu ft/s (2,390 m3/s) |

| Type | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

| Designated | October 28, 1988 |

Course

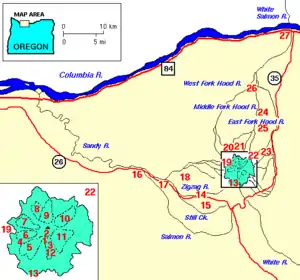

Issuing from Reid Glacier on the southwest flanks of Mount Hood in the Cascade Range, the Sandy River flows generally west and then north for 57 miles (92 km) through Clackamas County and Multnomah County to the Columbia River at Troutdale.[8] In its first 12 miles (19 km), the Sandy River flows across Old Maid Flat, north of Zigzag Mountain in the Mount Hood Wilderness of the Mount Hood National Forest. In this initial stretch near the headwaters, it receives Rushing Water Creek from the left, Muddy Fork from the right, then Lost Creek and Horseshoe Creek from the left, and crosses under Lolo Pass Road just before receiving Clear Creek from the right. At about 41 miles (66 km) from the mouth, the Zigzag River enters from the left near the unincorporated community of Zigzag. From here the river runs roughly parallel to U.S. Route 26, which is on its left for about the next 20 miles (32 km). Just below Zigzag, the Sandy River passes the unincorporated community of Wemme on the left.[9][10]

At about 39 miles (63 km) from the mouth, the river receives Hackett Creek from the right, passes the unincorporated community of Brightwood shortly thereafter, and receives North Boulder Creek from the right. Barlow Trail County Park and remnants of the Barlow Road lie to the right along this stretch of the river. Between 38 miles (61 km) and 37 miles (60 km) from the mouth, the Salmon River enters from the left. Roughly 4 miles (6.4 km) later, Wildcat Creek enters from the left and then Alder Creek and Whiskey Creek, also from the left. The river passes the Marmot gauging station operated by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in cooperation with Portland General Electric at river mile (RM) 29.8 (river kilometer (RK) 48.0). The unincorporated community of Marmot lies to the right of the river on a ridge—the Devil's Backbone—separating the Sandy River from the Little Sandy River to the north.[9][10][11]

About 4 miles (6.4 km) below the Marmot gauge, the river receives Badger Creek from the left. It passes under Ten Eyck Road about 24 miles (39 km) from the mouth, flowing by the city of Sandy on the left, shortly thereafter and receiving Cedar Creek, home of the Sandy Fish Hatchery, from the left. At about 22 miles (35 km) from the mouth, the river turns away from Highway 26 and flows generally north-northwest for the rest of its course. About 3 miles (4.8 km) further downstream, the river passes Dodge Park on the right, receives the Bull Run River from the right and passes a second USGS gauge at RM 18.4 (RK 29.6). Shortly thereafter, Walker Creek enters from the right. Between 17 miles (27 km) and 16 miles (26 km) from the mouth, the Sandy River enters Multnomah County, curves back into Clackamas County, and re-enters Multnomah County. About 1 mile (1.6 km) further downstream, Bear Creek enters from the left, and the river flows around Indian John Island.[6][9][10]

Soon Trout Creek, Gordon Creek, and Buck Creek all enter from the right as the river winds through Oxbow Regional Park between 14 miles (23 km) and 11 miles (18 km) from the mouth. Passing Camp Collins about 1 mile (1.6 km) later, the river receives Big Creek from the right. Dabney State Recreation Area is on the right about 4 miles (6.4 km) later. Lewis and Clark State Recreation Site is on the right and Troutdale on the left at about 3 miles (5 km) from the mouth, where Beaver Creek enters from the left. Shortly thereafter, the river passes under Interstate 84 and flows by Portland-Troutdale Airport, which is on the left about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the mouth. The Sandy River then joins the Columbia River about 120 miles (190 km) from where the larger river enters the Pacific Ocean. The confluence is about 14 miles (23 km) east of Portland, near the lower end of the Columbia River Gorge.[9][10]

Discharge

Measured by a United States Geological Survey (USGS) gauge downstream of the Sandy's confluence with the Bull Run River, 18.4 miles (29.6 km) from the mouth, the river's average discharge is 2,300 cubic feet per second (65 m3/s). The maximum daily recorded flow is 84,400 cubic feet per second (2,390 m3/s), and the minimum is 45 cubic feet per second (1.3 m3/s).[6]

History

Archeological evidence suggests that Native Americans lived along the lower Columbia River as early as 10,000 years ago. The area near what later became The Dalles, on the Columbia east of the mouth of the Sandy River, eventually became an important trading center. The Indians established villages on floodplains and traveled seasonally to gather huckleberries and other food on upland meadows, to fish for salmon, and to hunt elk and deer. Although no direct evidence exists that these lower-Columbia Indians traveled up the Sandy, it is likely that they did. Traces of these people include petroglyphs carved into the rocks of the Columbia River Gorge. More recently, within the past few thousand years, Indians created trails across the Cascade Range around Mount Hood. The trail network linked the trading center at Wascopam, near The Dalles, to settlements in the Willamette Valley. One popular trail crossed over Lolo Pass and another, which later became the Barlow Road, met the Lolo Pass trail roughly where the Zigzag and Salmon rivers enter the Sandy. Indians from villages along the Columbia, Clackamas, and other rivers also traveled by water to the lower Sandy River area to fish for salmon and to gather berries, nuts and roots.[5]

In 1792 William Robert Broughton of the Vancouver Expedition explored the lower Columbia River. He named the Sandy River "Baring River", but noted the existence of a large sand bank that nearly blocked the Columbia River at the mouth of the Sandy River.[12] In 1805 and again in 1806, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition explored the lower stretches of the Sandy River as they traveled down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean.[13] Mount Hood, at the river's headwaters, had erupted a few years earlier, causing loose sediment to collect at the river's mouth.[13] On November 3, 1805, William Clark wrote: "I arrived at the entrance of a river which appeared to Scatter over a Sand bar, the bottom of which I could See quite across and did not appear to be 4 Inches deep in any part; I attempted to wade this Stream and to my astonishment found the bottom a quick Sand, and impassable ...".[12]

One of the first documented visits by European-Americans to the upper Sandy River basin occurred in 1838, when Daniel Lee, the nephew of missionary Jason Lee, used the Indian trail over Lolo Pass to drive cattle from a Methodist mission in the Willamette Valley to a mission in Wascopam. Other pioneers later used the trail to drive livestock over the mountains. The first wagons came over the Cascades in 1840, and in 1843 the great east-west migration of settlers to the Oregon Territory began. The Barlow Road, along the Indian trail leading west from the Lolo Trail, opened in 1846 and became popular with new settlers. A branch of this road followed the Devil's Backbone between the Sandy and the Little Sandy watersheds.[5]

Hydroelectric decommissioning

Until October 2007, the river was dammed and the flow rate regulated. The Bull Run Hydroelectric Project diverted water from the Sandy River at Marmot Dam to Little Sandy Dam on the Little Sandy River. From there the water flowed to Roslyn Lake, an artificial creation, through a wood box flume. The lake supplied the 22-megawatt Bull Run hydroelectric powerhouse and emptied into the Bull Run River.[14]

In 2007, engineers demolished Marmot Dam with 650 pounds (290 kg) of explosives.[15] When in 2008 they demolished Little Sandy Dam,[14] Roslyn Lake ceased to exist. After Marmot Dam was gone, the Sandy flowed freely for the first time since 1912,[14] and the subsequent alterations restored the Little Sandy River to steelhead and salmon runs for the first time in a hundred years. Portland General Electric, the dams' owner, donated 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) of land in the vicinity to a nature reserve.[16] With the Marmot Dam removal and other habitat restoration in the Sandy River Basin Salmon, Steelhead, and Pacific lamprey are making a comeback. The Lower Salmon River upstream of the former Marmot Dam in recent years has undergone extensive riparian and river restoration. Engineered log jams and the opening of former side channels blocked by the Army Corps of Engineers since the devastating 1964 floods have taken place.

Recreation

In 1988, Congress added about 25 miles (40 km) of the Sandy to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. The designation applies to two separate segments. One, administered by the U.S. Forest Service, covers 12.4 miles (20.0 km) from the headwaters to the Mount Hood National Forest boundary. The other, administered by the Bureau of Land Management, covers 12.5 miles (20.1 km) between Dodge Park and Dabney Park. Of the total, 4.5 miles (7.2 km) were designated "wild", 3.8 miles (6.1 km) "scenic", and 16.6 miles (26.7 km) "recreational".[17]

A wide variety of recreational activities occur along the Sandy. Hiking, fishing, backpacking, and camping are popular along the upper river. Hikes include the trail to Ramona Falls, a well-known waterfall. Other uses of the upper river and its surrounds include kayaking and cross-country skiing. Fishing, picnicking, non-motorized boating and floating are among popular activities on the lower river.[17]

Parks along the river include Dodge Park, Oxbow Regional Park, Dabney State Recreation Area, Lewis and Clark State Recreation Site, and Glenn Otto Park.[9][10]

See also

References

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003). Oregon Geographic Names, Seventh Edition. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. pp. 846–47. ISBN 0-87595-277-1.

- "Sandy River". Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). United States Geological Survey (USGS). November 28, 1980. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- Source elevation derived from Google Earth search using GNIS source coordinates.

- Palmer, Tim (2014). Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-87071-627-0.

- Taylor, Barbara (December 1998). "Salmon and Steelhead Runs and Related Events of the Sandy River Basin - A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Portland General Electric. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- "USGS 14142500 Sandy River Below Bull Run River, near Bull Run, OR". United States Geological Survey. 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- Average discharge rate was calculated by adding average annual discharge rates for 10 calendar years, 1994–2003, from USGS records and dividing by 10.

- The nearby Sandy Glacier drains into Muddy Fork, a tributary of the Sandy River, rather than directly into the main stem.

- Oregon Atlas & Gazetteer (Map) (1991 ed.). DeLorme Mapping. § 61–62, 67. ISBN 0-89933-235-8.

- "Online Topographic Maps from the United States Geological Survey: Mount Hood North, Bull Run Lake, Hickman Butte, Rhododendron, Brightwood, Bull Run, Sandy, Washougal, and Camas quadrants". TopoQuest. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- "USGS 14137002 Sandy River Below Marmot Dam, Near Marmot, OR". United States Geological Survey. 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- O'Connor, Jim E. (Fall 2004). "The Evolving Landscape of the Columbia River Gorge: Lewis and Clark and Cataclysms on the Columbia". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 5 (103). Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2008 – via The History Cooperative.

- "Description: Mount Hood Volcano, Oregon". United States Geological Survey. 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- "Sandy River". Portland General Electric. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- Tetzler, Cindy (July 24, 2007). "Engineers Blow Up Dam on Oregon's Sandy River". 9news.com. KUSA-TV. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- "A River Released to the Wild". The Oregonian (Sunrise ed.). Portland, Oregon. July 29, 2007. p. E04. Retrieved August 31, 2015 – via Newsbank.

- "Sandy River, Oregon". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved August 31, 2015.