Saviour Bernard

Saviour Bernard (1724-1806) was a Maltese medical practitioner, a scientist, and a major philosopher. His areas of specialisation in philosophy were mostly philosophical psychology and physiology.[1]

Saviour Bernard | |

|---|---|

| Born | 29 November 1724 |

| Died | 7 March 1806 (81 years) |

| Occupation | Medicine, Philosophy |

Life

Beginnings

Bernard was born at Valletta, Malta, on November 29, 1724, from French parents. His family seems to have been well-off, enough, at least, to give Bernard a good initial formation, one which was probably better than that of his peers.

At the young age of nineteen, in 1743, Bernard was sent to the south of France, at Aix-en-Provence, to study medicine and surgery at the University of Aix-en-Provence there. He graduated in June 1749, at the age of twenty-four.

Professional career

It was during that same year that Bernard, then already back in Malta, published in Sicily what turned out to be his life’s major work, entitled Trattato Filosofico-Medico dell’Uomo (See below: Magnum opus).

In 1752, Bernard was appointed the principal officer of public health by the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitallers, Manuel Pinto da Fonseca. He was also appointed medical superintendent of two major hospitals of the Knights Hospitallers, Santo Spirito, at Rabat, and Lazzaretto, on Manoel Island.

At the end of the 18th century, Bernard worked hard to cure the diseased stricken by the epidemic influenza. On this occasion he is said to have showed outstanding proficiency and resourcefulness.

Retirement and death

During the very last years of the Knights Hospitallers’ rule, when Bernard was in his late seventies, the Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim graciously granted the aged doctor and philosopher a pension equal to his salary, something which was not normal practice in those days. In return, Bernard continued to provide his services whenever asked for as long as his health held out. He finally retired in 1801, at the age of seventy-seven, when by then the Knights Hospitallers had long been expelled from Malta.

Bernard died at Rabat, Malta at the age of eighty-two on March 7, 1806.

Magnum opus

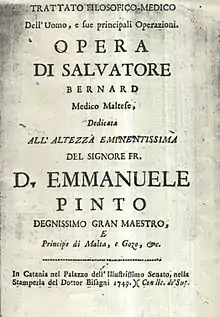

- Trattato Filosofico-Medico dell’Uomo e Sue Principali Operazioni (A Philosophical-Medical Study on Man and his Principal Operations; 1749)[2] – Despite having almost certainly been composed in France, the book was written in Italian and published in Catania, Sicily, at the printing press of the senate there, which was run by Mr. Bisagni. It was dedicated to the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitallers, Manuel Pinto da Fonseca. Essentially, the work is a philosophical study thoroughly based on medical observations of human beings and animals.

The book, which is composed of 111 pages, opens with a dedicatory letter and a table of contents. Then it is divided in eight chapters. In his opening letter, Bernard goes at some length to justify the significance of his work despite his relatively young age (of just twenty-four). The chapters respectively deal with (1) the nature of human beings, (2) their bodily functions, (3) their sensitive faculties, (4) their intellectual faculties, (5) the relation between their sensitive and intellectual faculties, (6) the dependence of bodily movements upon the intellect, (7) the effect of the intellect upon bodily movements, and finally (8) the nature of the ‘internal life’ of the intellect.

Quotes

These are a few quotations from Bernard’s Trattato:[3]

- “Amongst the many calamities brought upon the human race by the first sin of Adam, Ignorance, to which we are all indifferently subject, is certainly not the least important.” – Prologue

- “Man emerges into light enriched with the beautiful gift of reason, which arms him, clothes him and strengthens him, in such a way that it makes him Lord and absolute Master of all other creatures, whether their earthly bodies be animate or inanimate.” – Chapter 1

- “The human body is a machine so artful and complicated in its many parts, so well planned together and meshed from so many sides that all the intellects united together would hardly suffice to understand its construction and symmetry. Therefore, not without reason is it called the small world.” – Chapter 2

- “This is the principal role of the senses, namely watching over the preservation of one’s own individuality.” – Chapter 3

- “I hold that since in this there is no contradiction, one can cautiously conjecture that body or matter can think, and that God can, if He wants, grant to it this so noble faculty and establish that its various movements and diverse figures are its various perceptions and diverse thoughts; nor do I find reasons that prohibit me to believe it.” – Chapter 4

- “If thought and cognition are not properties belonging only to spirits, but can also be compatible with bodies, it can be inferred that animals can know, feel and have many other ideas and perceptions without having a spiritual soul, but by means solely of some movements which their organs perform.” – Chapter 4

- “It is not necessary for a King to be present in all the cities of his kingdom in order to govern and know that which occurs in its various provinces: it suffices that he be at his seat of command and overall rule. Likewise the soul, which is the Queen of the body, does not need to be present and united to all of its parts. It suffices for the soul to be at its seat of command and rule over all the movements of its body which are subordinated to its jurisdiction. There, finally, all the parts of the body send, so to speak, accounts of all that occurs in them.” – Chapter 5

- “The body lives independently of the soul, and all the others vital functions are fulfilled in it without its concurrence.” – Chapter 5

- “The body dies not because the soul separates itself from it. The soul divorces itself from its body because the latter dies and ceases to live.” – Chapter 5

- “For us good is all that which is apt to bring us happiness and augment it in us, by means of the pleasure, merriment and contentment brought to us by its possession and enjoyment, or else that which can hive away or remove from us some pain, sadness, or other nuisance.” – Chapter 6

- “Imagining does not differ from sensing, except in terms of greater or lesser vivacity.” – Chapter 7

Other works of philosophical interest

Both of the following works contain interesting reflections which might interest philosophy. The second one especially. It is written in a curious style, its theme is rather intriguing, and the philosophical arguments brought forth are quite interesting.

- Notamenta (Annotations; 1749)[4] – A manuscript in Latin composed by Bernard during the same year that his Trattato was published.[5] The document is made up of 91 back-to-back folios, and contains a whole series of notes organised in alphabetical order. The work deals with a lot of subjects. Most of them are of a historical nature related to Malta’s history. Others are interesting from a sort of sociological point of view. It is in this sense that these latter ones might be of interest to philosophy.

- De Fluidorum (Concerning the Nature of a Fluid; 1751)[6] – The whole title of this work is De Fluidorum et Materiæ Electricæ Natura concertatio sive Dissertatio Apologetica (Concerning the Nature of a Fluid and the Nature of the Electrical Matter which it contains, or a Defensive Study). The manuscript uses the genre of a report of a (probably imagined) discussion between a Sicilian, Benedict Genuisi, on one side, and John Bruno and Bernard, both Maltese, on the other.[7] The whole document is made of just 35 folios, and is divided in three main parts. The first part is written in Italian supposedly by Genuisi. It deals with two main themes: the nature of a fluid, and whether electrical energy is transmitted through a fluid or, rather, through sulphate acid. Herein, Genuisi answers to four objections which Bruno and Bernard have raised. Aristotle is quoted various times. The second and third parts, both written in Latin, respectively report the answers of Bruno and Bernard, in which each goes into some detail to explain points already mentioned in the first part of the work. While Bruno produces two experiments to prove his case, Bernard insists that experiments must be proved philosophically. In support of his arguments, Bernard calls forth the authority of Locke, Descartes and Robert Boyle.

Other manuscripts

The following three tracts, all unpublished, are not of any philosophical interest. They might, however, be interesting and valuable from a medical point of view.

- Tractatus de Morbis (A Study of Illnesses) – In Latin.

- Sull’Origine della Pazzia (On the Origin of Madness) – In Italian.

- Delle Epidemie Febbrili Maligne (Concerning Malign Feverish Epidemics) – In Italian.

Estimation

Political views

Bernard lived during the turbulent times when the Knights Hospitallers were ousted from the Maltese islands by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798. Despite the fact that the French, in turn, were overthrown by the Maltese, and later driven out in 1800 by the British, the Knights Hospitallers were not reinstated. Bernard lived his last years during the ‘temporary’ rule of the British.

These developments must not have been to Bernard’s liking. He was very proud of his Christian faith and also very fond of the Knights Hospitallers. To see them reduced to a nonentity must have been difficult for him to acknowledge.

Philosophy

In terms of his philosophical positions, Bernard must be considered to be a modern philosopher.[8] He wrote in the pre-Kantian period of modern philosophy when two main schools of thought, namely rationalism and empiricism, opposed each other despite their common inheritance of the characteristic Cartesian prejudice of the whole of modern philosophy – viz. that what man knows directly and immediately are not things themselves but his own ‘ideas’.

Bernard was not a rationalist in the sense that he adopts the ‘geometrical method’ which characterised the writings of Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz. Nor is Bernard a rationalist in the sense of excluding supernatural faith. While Descartes in the Discourse on Method attempts to construct knowledge entirely on reason and not on dogma or faith, Bernard takes the existence of God for granted and accepts the immortality of the soul on the basis of faith. Bernard can be labelled a rationalist only in a very wide sense; only in so far as he highly values the rational qualities of man (bequeathed upon him by God). His emphasis on man as a rational animal, and his discourse in the preface to his Trattato concerning the spirit of his attempt to illumine the minds of men, are grounds for considering his work to be part and parcel of the enlightenment culture of the 18th century.

In any stricter (epistemological) sense of the word ‘rationalist’, Bernard should rather be considered as adhering to the opposite camp. He takes sensorial experience as the point of departure for the acquisition of knowledge. He criticises the theory of innate ideas – characteristic of the rationalist stream of thought in modern philosophy – and points out that the mind is at birth a tabula rasa or rather a blank slate awaiting ideas from experience. He thinks that ideas are derived from experience, and this is highly reminiscent of the empiricism of Locke. However, he does seem to have the greatest sympathy for Malebranche (who belongs, in the epistemological sense of the word, to the rationalist school) out of all philosophers, except on this basic issue of the origin of ‘ideas’.

There is hardly any indication whatsoever of indebtedness to Thomistic philosophy in Bernard’s work despite his repeated professions of deference to the Catholic Church. His tacit rejection, rather than explicit opposition, to the central features of the anthropology of Aquinas, notably its anti-dualism, is, however, not surprising and possibly unintended.

Appreciation

In academic circles, Bernard is revered more as a philosopher than as a medical doctor. This might be because his major writing, even if written in his youth, is more of a philosophical nature than anything else. It might be also due to the fact that Bernard is generally eclipsed by his more well-known contemporary, Joseph Demarco.

In any case, since 1995, when Bernard’s Trattato was presented to the public as a work worthy of philosophical consideration,[9] more and more attention was given to the work by philosophers. Unfortunately, Claude Falzon's excellent translation of it, made in 1998, is still to be published. Falzon’s work also includes a philosophical study of Bernard’s book as an introduction. Nevertheless, further investigations would certainly be more than fitting, especially to amplify the biographical data concerning Bernard’s life, times and also his professional and academic activities.

Further reading

- P. Cassar, ‘The neuro-psychiatric concepts of Dr. S. Bernard’, Scientia, Malta, XV, 1948, 1, 20-33.

- R. Mifsud Bonnici, Dizzjunarju Bijo-Bibliografiku Nazzjonali, Malta, 1960.

- P. Cassar, Medical History of Malta, London, Wellcome Historical Medical Library, 1964.

References

- Montebello (2001), Vol. I, pp. 49–50

- Montebello (2001), Vol. II, p. 235

- Falzon (1998)

- Montebello (2001), Vol. II, p. 64

- National Library of Malta, MS. 249.

- Montebello (2001), Vol. II, p. 176–177

- National Library of Malta, MS. 17.

- Falzon (1998), pp. 33–34

- Mark Montebello, Stedina ghall-Filosofija Maltija, PEG, Malta, 1995, pp. 105-106.

Sources

- Montebello, Mark (2001). Il-Ktieb tal-Filosofija f'Malta [A Source Book of Philosophy in Malta]. Malta: PIN Publications. ISBN 9789990941838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falzon, C. (1998). Introduction and Translation of 'Trattato Filosofico-Medico dell'Uomo' of Salvatore Bernard (Thesis). University of Malta.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)