School of Paris

School of Paris (French: École de Paris) refers to the French and émigré artists who worked in Paris in the first half of the 20th century.

The School of Paris was not a single art movement or institution, but refers to the importance of Paris as a center of Western art in the early decades of the 20th century. Between 1900 and 1940 the city drew artists from all over the world and became a centre for artistic activity. School of Paris was used to describe this loose community, particularly of non-French artists, centered in the cafes, salons and shared workspaces and galleries of Montparnasse.[1]

Before World War I the name was also applied to artists involved in the many collaborations and overlapping new art movements, between post-Impressionists and pointillism and Orphism, Fauvism and Cubism. In that period the artistic ferment took place in Montmartre and the well-established art scene there. But Picasso moved away, the war scattered almost everyone, by the 1920s Montparnasse had become a center of the avant-garde. After World War II the name was applied to another different group of abstract artists.

Early artists

Before World War I, a group of expatriates in Paris created art in the styles of Post-Impressionism, Cubism and Fauvism. The group included artists like Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani and Piet Mondrian. Associated French artists included Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. Picasso and Matisse have been described as the twin leaders (chefs d’école) of the school before the war.[2]

After World War I

The term "School of Paris" was used in 1925 by André Warnod to refer to the many foreign-born artists who had migrated to Paris.[3] The term soon gained currency, often as a derogatory label by critics who saw the foreign artists—many of whom were Jewish—as a threat to the purity of French art.[4] Art critic Louis Vauxcelles, noted for coining the terms "Fauvism" and "Cubism" (also meant disparagingly), called immigrant artists unwashed "Slavs disguised as representatives of French art".[5] Waldemar George, himself a French Jew, in 1931 lamented that the School of Paris name "allows any artist to pretend he is French...it refers to French tradition but instead annihilates it."[6]

School of Paris artists were progressively marginalized. Beginning in 1935 art publications no longer wrote about Chagall, just magazines for Jewish audiences, and by June 1940 when the Vichy government took power, School of Paris artists could no longer exhibit in Paris at all.[6]

The artists working in Paris between World War I and World War II experimented with various styles including Cubism, Orphism, Surrealism and Dada. Foreign and French artists working in Paris included Jean Arp, Joan Miró, Constantin Brâncuși, Raoul Dufy, Tsuguharu Foujita, artists from Belarus like Michel Kikoine, Pinchus Kremegne, the Lithuanian Jacques Lipchitz, the Polish artists Marek Szwarc and Morice Lipsi and others such as Russian-born prince Alexis Arapoff.[7]

A significant subset, the Jewish artists, came to be known as the Jewish School of Paris or the School of Montparnasse.[8] The "core members were almost all Jews, and the resentment expressed toward them by French critics in the 1930s was unquestionably fueled by anti-Semitism."[9] One account points to the 1924 Salon des Indépendants, which decided to separate the works of French-born artists from those by immigrants; in response critic Roger Allard referred to them as the School of Paris.[9][10] Jewish members of the group included Emmanuel Mané-Katz, Chaim Soutine, Adolphe Féder, Chagall, Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel, Moïse Kisling, Maxa Nordau and Shimshon Holzman.[11]

The artists of the Jewish School of Paris were stylistically diverse. Some, like Louis Marcoussis, worked in a cubist style, but most tended toward expression of mood rather than an emphasis on formal structure.[8] Their paintings often feature thickly brushed or troweled impasto. The Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme has works from School of Paris artists including Pascin, Kikoine, Soutine, Orloff and Lipschitz.[12]

After World War II

In the aftermath of the war, "nationalistic and anti-Semitic attitudes were discredited, and the term took on a more general use denoting both foreign and French artists in Paris".[4] But although the "Jewish problem" trope continued to surface in public discourse, art critics ceased making ethnic distinctions in using the term. While in the early 20th century French art critics contrasted The School of Paris and the École de France, after World War II the question was School of Paris vs School of New York.[13]

Post-World War II (Après-guerre), the term "School of Paris" often referred to tachisme, and lyrical abstraction, a European parallel to American Abstract Expressionism. These artists are also related to CoBrA.[14] Important proponents were Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Soulages, Jean-Michel Coulon, Nicolas de Staël, Hans Hartung, Serge Poliakoff, Bram van Velde, Georges Mathieu, Jean Messagier, Zoran Mušič,and Fahrelnissa Zeid, among others. Many of their exhibitions took place at the Galerie de France in Paris, and then at the Salon de Mai where a group of them exhibited until the 1970s.

Selected artists

- Constantin Brâncuși, Romanian-born sculptor, considered a pioneer of modernism,[2] arrived in Paris in 1904

- Marc Chagall lived in Paris from 1910 to 1914[15] then again after his exile from the Soviet Union in 1923; Jewish; was arrested in Marseilles by the Vichy government but escaped to the US with help from Alfred H. Barr, Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art, and collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg, among others[16]

- Giorgio de Chirico, an Italian who showed the first signs of magical realism later highlighted in Surrealist works, lived in Paris 1911-1915 and again in the 1920s[15]

- Jean-Michel Coulon, French painter, had the particularity of having kept his work almost secret over his lifetime

- Robert Delaunay, French painter, co-founder of Orphism with his wife Sonia

- Sonia Delaunay,[17] wife of Robert, born Sarah Stern in the Ukraine[5]

- Isaac Dobrinsky[8]

- Jean Dubuffet[18]

- François Zdenek Eberl, a naturalised French painter, a Catholic born in Prague

- Tsuguharu Foujita, Japanese-French painter

- Boris Borvine Frenkel a Jewish painter from Poland

- Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel, father of modern Israeli art sent his students to learn in Paris. Carried the influence of the School Of Paris to Israel which up to that point was dominated by Orientalism.

- Leopold Gottlieb, Polish paintier[8]

- Philippe Hosiasson, a Ukrainian-born painter associated with the Ballets Russes

- Max Jacob

- Wassily Kandinsky,[2] Russian abstract artist, arrived in 1933

- Georges Kars, Czech painter[8]

- Moïse Kisling,[9] lived at La Ruche[16]

- Pinchus Krémègne[9]

- Michel Kikoine, born in Belarus

- Jacques Lipchitz, lived at La Ruche;[16] Jewish cubist sculptor; took refuge from the Germans in the US[5]

- Morice Lipsi, Jewish sculptor of Polish origin

- Jacob Macznik (1905-1945), born in Poland, arrived in Paris in 1928, died at the hands of the Nazis 1945.[19][20] A young and highly regarded member of the École de Paris in the 1930s, prior to its decimation by the Reich.[21]

- Louis Marcoussis, had a studio in Montparnasse[16]

- Abraham Mintchine[8]

- Yervand Kochar

- Amedeo Modigliani, arrived in Paris in 1906,[15] lived at La Ruche[16]

- Piet Mondrian, a Dutch abstract artist, moved to Paris in 1920[2]

- Elie Nadelman, lived in Paris for ten years[17]

- Chana Orloff, Jewish,[22] portrait sculptor[17] worked in Montparnasse[16]

- Jules Pascin,[9] Bulgarian-born Jew[5]

- Chaim Soutine, born in a shtetl near Minsk,[5] was unable to get a US visa when the German Army invaded, and lived in hiding under the occupation until he died in 1943 at age 50. Soutine, a friend of Modigliani, arrived in Paris in 1913[15] and lived at La Ruche[16]

- Avigdor Stematsky

- Kostia Terechkovitch was born in Russia and arrived in Paris in 1920, where he was part of the Montparnasse émigré group.

- Maurice Utrillo

- Kuno Veeber, Estonian artist, arrived in Paris in 1924[23]

- Max Weber, German artist, arrived in Paris in 1905[17]

- Ossip Zadkine,[9] born in Belarus and lived at La Ruche[16]

- Faïbich-Schraga Zarfin, born in Belarus, friend of Soutine

- Alexandre Zinoview born in 1889 in Russia, died in France in 1977. Arrived in Paris in 1908. Volunteered for the French Foreign Legion in World War I, became a naturalised French citizen in 1938.

- Fahrelnissa Zeid

Associated with artists

- Albert C. Barnes, whose buying trip to Paris gave many School of Paris artists their first break[9]

- Waldemar George, unfriendly art critic[9]

- Paul Guillaume, art dealer introduced to de Chirico by Apollinaire[24]

- Jonas Netter, an art collector[9]

- Madeline and Marcellin Castaing, collectors[9]

- André Warnod, a friendly art critic[9]

- Léopold Zborowski, art dealer, represented Modigliani and Soutine[9]

Musicians

In the same period, the School of Paris name was also extended to an informal association of classical composers, émigrés from Central and Eastern Europe to who met at the Café Du Dôme in Montparnasse. They included Alexandre Tansman, Alexander Tcherepnin, Bohuslav Martinů and Tibor Harsányi. Unlike Les Six, another group of Montparnasse musicians at this time, the musical school of Paris was a loosely-knit group that did not adhere to any particular stylistic orientation.[25]

Gallery

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_44.8_x_36.8_cm%252C_Korban_Art_Foundation..jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, Femme au Chapeau (Woman with a Hat), c.1906, oil on canvas, 44.8 x 36.8 cm, Korban Art Foundation

Jean Metzinger, Femme au Chapeau (Woman with a Hat), c.1906, oil on canvas, 44.8 x 36.8 cm, Korban Art Foundation%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_private_collection.jpg.webp) Marc Chagall, Still-life (Nature morte), 1912, oil on canvas, private collection

Marc Chagall, Still-life (Nature morte), 1912, oil on canvas, private collection Robert Delaunay, Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon, 1912–13, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Robert Delaunay, Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon, 1912–13, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City Moïse Kisling, Nu sur un divan noir, 1913, oil on canvas, 97 x 130 cm

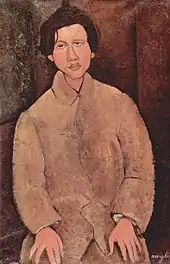

Moïse Kisling, Nu sur un divan noir, 1913, oil on canvas, 97 x 130 cm Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Chaïm Soutine, 1916

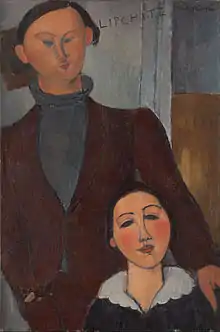

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Chaïm Soutine, 1916 Amedeo Modigliani, Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, 1916

Amedeo Modigliani, Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, 1916 Jacques Lipchitz, Portrait of Jean Cocteau, 1920

Jacques Lipchitz, Portrait of Jean Cocteau, 1920_-_Mus%C3%A9e_d'art_et_d'histoire_du_Juda%C3%AFsme.jpg.webp) Chaim Soutine, Céret Landscape, c. 1920, oil on canvas, 55 x 65 cm, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme

Chaim Soutine, Céret Landscape, c. 1920, oil on canvas, 55 x 65 cm, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme

References

- "School of Paris". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- "Glossary of art terms: School of Paris". Tate Gallery. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- André Warnod, Les Berceaux de la jeune peinture : Montmartre, Montparnasse, l'École de Paris, Edition Albin Michel, 1925

- Alley, Ronald. "Ecole de Paris." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web.

- Deborah Solomon (June 25, 2015). "Montmartre/Montparnasse". New York Times Review of Books. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- Romy Golan (2010). "The École Francaise vs the École de Paris: The Debate about the Status of Jewish Artists in Paris between the Wars". In Rose-Carol Washton Long; Matthew Baigell; Milly Heyd (eds.). Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Anti-Semitism, Assimilation, Affirmation. Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry series. UPNE. p. 86. ISBN 978-1584657958 – via Google Books.

- Boston College University Libraries

- Roditi, Eduard (1968). "The School of Paris". European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe, 3(2), 13–20.

- Wendy Smith, The immigrants who were ‘School of Paris’ artists in early 20th century, Washington Post, June 19, 2015

- Stanley Meisner, Albert Barnes and his pursuit of non-French art in Paris, Los Angeles Times, May 1, 2015

- Schechter, Ronald; Zirkin, Shoshanna (2009). "Jews in France". In M. Avrum Ehrlich (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. 3. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 820–831, here: 829. ISBN 9781851098736. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- Jarrasse, Dominique, Guide du patrimoine juif parisien, éditions Parigramme, 2003, pages 213-225

- Malcolm Gee, Between Paris and New York: Critical constructions of 'Englishness', c. 1945 - 1960, Art Criticism Since 1900, Manchester University Press, 1993, p. 180. ISBN 0719037840

- Auber, Nathalie, 'Cobra after Cobra' and the Alba Congress: From Revolutionary Avant-Garde To Situationist Experiment, Third Text 20.2 (2006), Art Source. Web. 14 Sept. 2015.

- James Voorhies (October 2004). "School of Paris". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "The School of Paris". Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2017.

- John Russell, Art Review: Jewish Artists Who Made Paris Their Exuberant Garret, New York Times, March 10, 2000

- "The School of Paris: Paintings from the Florence May Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx Collection". Museum of Modern Art. 1965. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- http://www.macznik.org

- Peintres Juifs A Paris: École de Paris, Nadine Nieszawer et al, Éditions Denoël, Paris, 2000

- Undzere Farpainikte Kinstler, Hersh Fenster, Imprimerie Abècé. 1951

- PJ Birnbaum (2016). "Chana Orloff: A modern Jewish woman sculptor of the School of Paris". Journal of Modern Jewish Studies. 15 (1, 2016): 65. doi:10.1080/14725886.2015.1120430. S2CID 151740210.

- Õhtuleht Näitused 9 May 1998. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Robert Jenson, Why the School of Paris Is Not French, Purdue University, Artl@s Bulletin, 2013

- Korabelʹnikova, Li͡udmila Zinovʹevna (2008). "European Destiny: The Paris School". Alexander Tcherepnin: The Saga of a Russian Emigré Composer. Indiana University Press. pp. 65–70. ISBN 978-0-253-34938-5.

Further reading

- Stanley Meisler (2015). Shocking Paris: Soutine, Chagall and the Outsiders of Montparnasse. Palgrave Macmillan.

- West, Shearer (1996). The Bullfinch Guide to Art. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8212-2137-2.

- Nieszawer, Nadine (2000). Peintres Juifs à Paris 1905-1939 (in French). Paris: Denoel. ISBN 978-2-207-25142-3.

- Painters in Paris: 1895-1950, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2000

- Paris in New York: French Jewish Artists in Private Collections, Jewish Museum, New York, 2000

- Windows on the City: The School of Paris, 1900–1945, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 2016

- The Circle of Montparnasse, Jewish Artists in Paris 1905-1945, From Eastern Europe to Paris and Beyond, exhibition catalogue Jewish Museum New York, 1985

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to École de Paris. |

- (in French and English) Nadine Nieszawer's website, dedicated to the School of Paris 1905-1939 (includes many biographies)

- The Second Spanish School of Paris

- Website for Jewish art of the School of Paris circle

- school-of-paris.org : community website open to any fan to École de Paris in the world

- The School of Paris 1945 – 1965

- Guggenheim holdings by School of Paris artists