Alexandre Tansman

Alexander Tansman (Polish: Aleksander Tansman, French: Alexandre Tansman; 12 June 1897 – 15 November 1986) was a Polish composer, virtuoso pianist and conductor of Jewish origin, since 1938 a French citizen. One of the earliest representatives of neoclassicism, associated with École de Paris, he was praised for his mastery in orchestration, instrumentation and his original approach to harmony and form. A globally recognized composer.[1][2]

Early life and heritage

Tansman was born and raised in the Polish city of Lodz during the era when Poland did not exist as an independent state, being part of Tsarist Russia. His parents were both natives of Pinsk. His father Moshe Tancman / Tantzman (1868-1908) died when Alexander was 10 and his mother Hannah (nee Hurwicz / Gourvitch, 1872-1935) reared him and his older sister Teresa (born in 1895) alone.[3][4]

The composer wrote the following about his childhood and heritage in a 1980 letter to an American researcher: "... my father's family came from Pinsk and I knew of a famous rabbi related to him. My father died very young, and there were certainly two, or more branches of the family, as ours was quite wealthy: we had in Lodz several domestics, two governesses (French and German) living with us etc. My father had a sister who settled in Israel and married there. I met her family on my [concert] tours in Israel. ... My family was, as far as religion is concerned, quite liberal, not practicing. My mother was the daughter of prof. Leon Gourvitch, quite a famous man".[5]

Among his first music teachers were Wojciech Gawronski (a student of Moritz Moszkowski and Johannes Brahms) and Naum Podkaminer (a student of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov).

Career

Although he began his musical studies at the Lodz Conservatory, his doctoral study was in law at the University of Warsaw. On January 8, 1919 Tansman won the first composers' competition held in independent Poland. In the fall of 1919, encouraged by his mentors Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Henryk Melcer-Szczawinski and Zdzislaw Birnbaum, Tansman decided to continue his musical career in Paris.[6] His musical ideas were accepted there, influenced and favoured by composers Maurice Ravel, Albert Roussel, Jacques Ibert, Igor Stravinsky, musicologists and critics Émile Vuillermoz, Boris de Schloezer, Alexis Roland-Manuel, Arthur Hoérée, conductors André Caplet, Gaston Poulet, Vladimir Golschmann. Though Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud tried to persuade him to join Les Six, he declined, stating a need for creative independence. Nevertheless, he was one of the earliest and leading representatives of neoclassicism, along with Stravinsky, Les Six, Sergei Prokofiev, Paul Hindemith, Alfredo Casella. He was also one of the most respected members of the international music group École de Paris, along with Bohuslav Martinů, Tibor Harsányi, Alexander Tcherepnin, Marcel Mihalovici, Conrad Beck.[7]

Tansman spoke seven languages (Polish, Russian, French, German, English, Italian, Spanish). His first wife was Romanian-Swiss Anna E. Brociner. They divorced in 1932. In 1937 he married a French pianist Colette Cras, daughter of the composer and naval commander, admiral Jean Cras.[8]

From the 1920s Tansman's rise to fame was meteoric, with works conducted by such world-famous baton masters as Arturo Toscanini, Tullio Serafin, Willem Mengelberg, Walter Damrosch, Henry Wood, Serge Koussevitzky, Pierre Monteux, Otto Klemperer, Rhené-Baton, Walther Straram, Hermann Abendroth, Leopold Stokowski, Erich Kleiber, Adrian Boult, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Eugene Ormandy. Tansman follows Paderewski as the second Polish composer whose theatre piece - ballet Sextuor - was staged by the Metropolitan Opera (1927).[9]

In 1927 Nicholas Slonimsky called Tansman a "musical plenipotentiary of Poland in the Western World".[10]

In 1931, Irving Schwerke's book titled Alexandre Tansman, compositeur polonais (Alexander Tansman. The Polish Composer) appeared in Paris. It was devoted to the work of Tansman until 1930 and its reception, to his individual style, the aesthetics of his oeuvre and included a catalogue of his works.[2]

As Marcel Mihalovici noted, Tansman was one of the most prominent contemporary representatives of the centuries-old tradition of École de Paris: "This included musicians at Notre-Dame Cathedral during the Renaissance, and later Lully, Mozart, and Wagner. Not to mention Chopin, Falla, Enescu, Honegger, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Copland, and certainly our old colleague Alexander Tansman".[11]

In June 1938, four years after Stravinsky and in the same year as Bruno Walter, Tansman was granted French citizenship by the last president of the Third Republic Albert Lebrun.[6]

Tansman fled Europe as his Jewish background put him in danger with Hitler's rise to power. He moved to Los Angeles, thanks to the efforts of his friend Charlie Chaplin in founding a committee visa. In 1941 he could join there the circle of famous emigrated artists and intellectuals that included Igor Stravinsky, Thomas Mann, Arnold Schönberg, Alma Mahler, Franz Werfel, Emil Ludwig, Aldous Huxley, Lion Feuchtwanger, Adolph Bolm, Eugène Berman, Jean Renoir.[8]

During his American years Tansman toured a lot as pianist and conductor and wrote a wealth of music, including a few scores for Hollywood movies: i.e. Flesh and Fantasy, starring Barbara Stanwyck, a biopic of the Australian medical researcher Sister Elizabeth Kenny, starring Rosalind Russell, and Paris Underground, starring Constance Bennett. For the 1946 Academy Awards ceremony, he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture, for Paris Underground. In 1948 Tansman authored an essay monograph on the musical phenomenon of Stravinsky.[12]

When Alexander Tansman returned to Paris after the war, his European musical career started again all over Europe and his works were performed by the best orchestras and conductors, i.e. Jascha Horenstein, Rafael Kubelik, André Cluytens, Paul Kletzki, Charles Munch, Bruno Maderna, Paul van Kempen, Malcolm Sargent, Ferenc Fricsay, Charles Bruck, Øivin Fjeldstad, Jean Fournet, Franz Waxman, Georges Tzipine, Alfred Wallenstein, Eduard Flipse, Roger Wagner, Jean Périsson.[9]

During the last period of his life, he began to reestablish connections to Poland, though his career and family kept him in France, where he lived until his death in Paris in 1986. Since 1996, in his native city of Lodz, Alexander Tansman Association for the Promotion of Culture has been organizing the Alexander Tansman International Festival and Competition of Musical Personalities (Tansman Festival).[13]

Notable students of Tansman include Cristóbal Halffter, Leonardo Balada, Carmelo Bernaola, Yüksel Koptagel.

Music

Tansman was not only an internationally recognized composer, but was also a virtuoso pianist.[14] He performed five concert tours in the United States, the first one as a soloist under Serge Koussevitzky with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1927-1928). In 1932-1933, Tansman made an unprecedented artistic tour around the world - starting from the United States, through Japan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Ceylon, India and Egypt, to Italy - and performed for audiences including Emperor Hirohito of Japan and Mahatma Gandhi.[7][8]

Many musicologists have said that Tansman's music is written in the French neoclassical style of his adopted home and the Polish national style of his birthplace, also drawing on his Jewish heritage. Already on the edge of musical thought when he left Poland (critics questioned his chromatic and sometimes polytonal writing, both present in his early works), he adopted the extended harmonies of Maurice Ravel and later was compared to Alexander Scriabin - whom he met personally in 1914 - in his departure from conventional tonality.

His original style that has already manifested in the early 1920s, was often characterised as a combination of expressive colouring, intense lyrical qualities and prolific melodic inventiveness with the ideal clarity, aristocratic elegance and precision of structure. French, Belgian, Dutch, German, Austrian, Italian and American critics praised his mastery in orchestration, instrumentation and the use of orchestra, and pointed to his sophisticated music language, including such of his trademarks as the chord called "the skyscraper" and his individual approach to form, where he introduced the so-called "bridges".[15]

According to Alejo Carpentier Tansman was "one of the most gifted musical personalities of our times".[16]

He was indeed one of these Polish artists whose art truly injected itself into the circulation of the international art life. It is Tansman – along with Karol Szymanowski, who was fifteen years his senior – who was the first composer to interweave Polish music with a new language and aesthetics of the 20th century. However, Tansman went beyond the 19th century musical poetics and German patterns much more than Szymanowski.[17]

Tansman always described himself as a Polish composer: "It is obvious that I owe much to France, but anyone who has ever heard my compositions cannot have doubt that I have been, am and forever will be a Polish composer".[7] After Frédéric Chopin, Tansman may be one of the leading proponents of traditional Polish forms such as the mazurka or the polonaise; they were inspired by and often written in hommage to Chopin.[18] For these pieces, which ranged from lighthearted miniatures to virtuoso showpieces, Tansman drew on traditional Polish folk themes, adapted them to his distinctive style, thus enriched melodic and harmonic means of modern music language,[6] as well as instrumental colour and rhythmic variation. However, he did not write straight settings of the folk songs, as he states in a radio interview: "I have never used an actual Polish folk song in its original form, nor have I tried to reharmonize one. I find that modernizing a popular song spoils it. It must be preserved in its original harmonization. But Polish character is not solely expressed through folklore. There is something intangible in my music that reveals an aspect of my Polish origin".[19]

As Irving Schwerke accurately concluded: "Deeply Polish, thanks to France Tansman became universal".[2]

The key determining the Tansman’s artistic stance, was his constantly repeated efforts to create a new classical style. It did not mean sticking to neoclassicism in terms of the aesthetic and stylistic impact in the normative meaning. The discrepancy between Tansman’s composing practice and the basic principles of neoclassicism could be observed in the 1940s, although the signs of such an attitude were clearly present in his earlier works. Nevertheless, after World War II, Tansman implemented more radical techniques. He included some achievements of the contemporary avant-garde and was interested in purely qualitative characteristics of sounds. The coexistence of various constructing principles in one form led to the clash of different types of expression, which strengthened the drama, dynamics and power of presentation of his music. All this without breaking up with the ceaseless pursuit of his music: to find a new classical style.[17]

When reviewing Tansman's oratorio Isaiah, The Prophet in 1955, Alfred Frankenstein and Herbert Donaldson considered it "should be counted among major works of religious music" and admired "the composer's genius".[15]

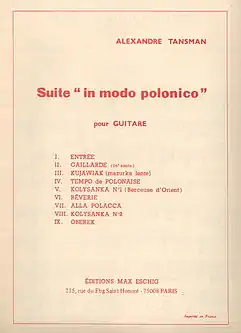

Tansman composed prolifically in most genres and wrote more than 300 works, including 7 operas, 10 ballets, 6 oratorios, 80 orchestral pieces (with 9 symphonies), virtuoso concertos and numerous works of chamber music, among them 8 string quartets, tens of pieces for piano, as well as pieces for the radio theatres and pedagogical works. He is also known for his guitar pieces, mostly written for Andrés Segovia – in particular the Mazurka (1925), Cavatine (1950), Suite in modo polonico (1962), Variations sur un theme de Scriabine (1972). Segovia frequently performed the works in recordings and on tour; it is today part of the standard repertoire.[20][21] Tansman's music has been performed by musicians such as Marya Freund, Jane Bathori, Louis Fleury, Léo-Pol Morin, Mieczyslaw Horszowski, Walter Gieseking, José Iturbi, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Alicia de Larrocha, Bronislaw Huberman, Héléne Jourdan-Morhange, Jascha Heifetz, Joseph Szigeti, Henry Temianka, Pablo Casals, Gregor Piatigorsky, Maurice Marechal, Enrico Mainardi, Gaspar Cassado, Marie-Louise Girod, quartets Pro Arte, Paganini, Pascal, Parrenin.[9]

Almost all his works have been now recorded on CDs.[22]

Selected works

Alexander Tansman's many hundreds of compositions include:

- Album polski (The Polish Album) for piano (1915-1916)

- Sérénade for orchestra (1916)

- String Quartet no. 1 (1917)

- Huit Mélodies japonaises for voice and piano or orchestra (1918)

- Impressions for orchestra (1920)

- Intermezzo sinfonico for orchestra (1920)

- Le Jardin du paradis (The Garden of Paradise), ballet (1922)

- String Quartet no. 2 (1922)

- Sonatine for piano (1923)

- Scherzo sinfonico for orchestra (1923)

- Sextuor, ballet (1923)

- La Danse de la Sorcière (The Witch's Dance) for orchestra (1923)

- Sinfonietta no. 1 for orchestra (1924)

- Sonata rustica for piano (1925)

- Piano Concerto no. 1 (1925)

- Symphonie no. 2 (1926)

- La Nuit kurde (The Kurdish Night), opera (1927)

- Piano Concerto no. 2 (1927)

- Suite for two pianos and orchestra (1928)

- Suite - Divertissement for violin, alto, cello and piano (1929)

- Cinq Pièces for violin and orchestra (1930)

- Triptyque (Triptych) for string orchestra (1930)

- Concertino for piano and orchestra (1931)

- Quatre danses polonaises (Four Polish Dances) for orchestra (1931)

- Symphonie no. 3 (Symphonie Concertante) for piano, violin, alto, cello and orchestra (1931)

- Septuor à Béla Bartók for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, alto, cello (1932)

- Rapsodie hébraïque for orchestra (1933)

- Fantaisie for cello and orchestra or piano (1936)

- Concerto for viola and orchestra (1936-1937)

- Concerto for violin and orchestra (1937)

- Variations sur un theme de Frescobaldi for string orchestra (1937)

- Piano Trio no. 2 (1938)

- Symphonie no. 4 (1939)

- La Toison d'or (The Golden Fleece), opera (1939) - world premiere: 2016, Tansman Festival, Lodz Grand Opera

- Rapsodie polonaise (The Polish Rhapsody) for orchestra (1940)

- Sextuor à cordes for 2 violins, 2 altos, 2 cellos (1940)

- Pièce concertante (Konzertstück) for piano (left hand) and orchestra to Paul Wittgenstein (1943)

- Symphonie no. 6 "In Memoriam" for mixed choir and orchestra (1944)

- Adam and Eve, Part 3 of Genesis Suite, for narrator and orchestra, collaboration with Arnold Schönberg, Darius Milhaud, Igor Stravinsky, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Ernst Toch and Nathaniel Shilkret (1944)

- Divertimento à Arnold Schönberg for oboe, clarinet, trumpet, cello and piano (1944)

- Kol-Nidrei for tenor solo, mixed choir and orgue (1945)

- Two Ancient Polish Religious Songs for mixed choir and orgue (1945)

- Concertino for guitar and orchestra (1945)

- Musique pour orchestre - Symphonie no. 8 (1948)

- Tombeau de Chopin for string quartet or string orchestra (1949)

- Isaïe le prophète (Isaiah, The Prophet), symphonic oratorio for tenor solo, choir and orchestra (1949-1950)

- Cavatine for guitar (1950)

- Concertino for oboe, clarinet and string orchestra (1952)

- Sonatina da camera for flute, violon, alto, cello and harpe (1952)

- Le Serment (The Oath), opera (1953)

- Concerto pour orchestre (1954)

- Hommage à Manuel de Falla for guitar and chamber orchestra (1954)

- Sonate no. 5 à la mémoire de Béla Bartók for piano (1955)

- Concerto for clarinet and orchestra (1957)

- Sabbataï Zévi, le faux messie (Sabbatai Zevi, the False Messiah), opera (1957-1958)

- Suite for bassoon and piano (1960)

- Musique de cour for guitar and chamber orchestra (1960)

- Psaumes (The Psalms) for tenor solo, choir, and orchestra (1960-1961)

- Résurrection (The Resurrection), ballet (1961-1962)

- Suite in modo polonico for guitar (1962)

- L'Usignolo di Boboli, opera (1963)

- Concerto à Charles Reneau for cello and orchestra (1963-1964)

- Hommage à Chopin for guitar (1966)

- Suite concertante for oboe and chamber orchestra (1966)

- Quatre mouvements for orchestra (1967-1968)

- Concertino for flute, piano and string orchestra (1968)

- Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam for orchestra (1968-1969)

- Stèle in memoriam Igor Stravinsky for orchestra (1972)

- Elégie à la mémoire de Darius Milhaud (1975)

- Les Dix Commandements (The Ten Commandments) for orchestra (1978-1979)

- Musique for harpe and orchestra (harpe and piano reduction 1981, orchestrated by Piotr Moss)

- Hommage à Lech Walesa for guitar (1982)

- Alla Polacca for alto and piano (1985)

7 operas (1927; 1939; Le roi qui jouait fou 1948; 1953; 1957-1958; 1963; Georges Dandin 1973-1974)

10 ballets (1922; 1923; Lumieres 1927; Le Cercel eternel 1929; Bric à Brac 1935; La Grand Ville à Kurt Jooss 1944; He, She and I 1946; Le train de nuit 1951; Les habits neufs du roi 1958-1959; 1961-1962)

9 symphonies (1917; 1926; 1931; 1939; 1942; Lyrique 1944; 1948; 1957-1958)

8 string quartets (1917; 1922; 1925; 1935; 1940; 1944; 1947; 1956)

Film music: Poil de Carotte (1932), La Chatelaine du Liban (1933), Flesh and Fantasy (1943), Paris Underground (1945), Destiny (1944), Sister Kenny (1946), The Bargee (1964)

Selected recordings

- Symphonie no. 5, Stele, Quatre mouvements - Czecho-Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra, Meir Minsky, conductor - Marco Polo, Naxos - 1991

- Complete Music for String Quartet: String Quartets nos. 2-8 - Silesian String Quartet - Etcetera - 1992

- Piano Sonatas and Sonatinas - Daniel Blumenthal, piano - Etcetera - 1993

- Concerto pour orchestre, Etudes for orchestra, Capriccio for orchestra - Moscow Symphony Orchestra, Antonio de Almeida, conductor - Marco Polo, Naxos - 1995

- Piano Concerto no. 2 - Polish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra in Cracow, Zygmunt Rychert, conductor, Marek Drewnowski, piano - Alexander Tansman Association for the Promotion of Culture, Joseph Hofmann Foundation - 1996

- Fantaisie - Igor Zubkovski, cello, Irina Khovanskaia, piano - Alexander Tansman International Competition of Musical Personalities, DUX - 1996

- Violin Concerto, Cinq Pieces, Quatre danses polonaises, Danse de la Sorciere, Rapsodie polonaise - Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Bernard Le Monnier, conductor, Beata Halska, violin - Olympia - 2000

- Divertimento, Sinfonia piccola, Sinfoniettas nos. 1, 2 - Virtuosi di Praga, Israel Yinon, conductor, Koch-Schwann - 2000

- Bric a Brac, Symphonie no. 4 - Bamberger Symphoniker, Israel Yinon, conductor - Koch-Schwann - 2000

- Cello concerto, Fantaisie for cello and orchestra, The Ten Commandments - Radio-Philharmonie Hannover, Israel Yinon, conductor, Sebastian Hess, cello - Koch-Schwann - 2001

- Isaie le prophete - Sinfonia Varsovia, Wojciech Michniewski, conductor, Alberto Mizrahi, tenor - City of Lodz, Alexander Tansman Association for the Promotion of Culture - 2004

- Genesis Suite - Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Gerard Schwarz, conductor, Tovah Feldshuh, Barbara Feldon, David Margulies, Fritz Weaver, Isaiah Sheffer - speakers - Milken Family Foundation, Naxos - 2004

- Suite in modo polonico, Cavatina - Andres Segovia, guitar - Deutsche Grammophon - 2004, 2006

- Musique pour orchestre - Symphonie no. 8 - Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Rafael Kubelik, conductor - Centrum Nederlandse Muziek, Radio Netherlands International, NM Classics - 2005

- Symphonies nos. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, Quatre mouvements - Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Oleg Caetani, conductor - Chandos - 2006-2008

- Variations sur un theme de Frescobaldi, Triptych, Musique pour cordes, Partita for string orchestra - Amadeus Polish Radio Chamber Orchestra, Agnieszka Duczmal, conductor - Alexander Tansman Association for the Promotion of Culture, Polish Radio - 2006

- Le Serment - Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Choeur de Radio France, Alain Atinoglu, conductor, Helene Collerette, violon, Marie Devellereau, Jean-Sebastein Bou, Fabrice Dallis, Alain Gabriel, Delphine Haidan - soloists, Eric Genovese, reciter - Radio France, Harmonia Mundi - 2007

- Sinfoniettas nos. 1, 2, Sinfonia piccola, Sinfonie de chambre - Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, Oleg Caetani, conductor - Chandos - 2009

- Piano Concerto no. 2 - Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Steven Sloane, conductor, David Greilsammer, piano - Naïve - 2010

- Piano Concertino, Piece concertante, Elegie, Stele - Branderburgisches Staatsorchester Frankfurt, Howard Griffiths, conductor, Christian Seibert, piano - CPO - 2012

- From Trio to Octet: Suite-Divertissement, Musique a cinque, Musique a six, Sextuor a cordes, Sonatina da camera, Tombeau de Chopin - Silesian String Quartet, Beata Bilinska, piano, Joanna Liberadzka, harpe, Jan Krzeszowiec, flute, Piotr Szymyslik, clarinet, Roman Widaszek, clarinet, Adam Krzeszowiec, cello, Krzysztof Firlus, double bass - Alexander Tansman Association for the Promotion of Culture, Classica - 2012

- Triptyque, Isaie le prophete - The Zimbler Sinfonietta, Choeur et Orchestre Philharmonique de la Radio d'Hilversum, Paul van Kempen, conductor - Forgotten Records - 2012

- Suite for oboe and orchestra, Clarinet Concerto, Concertino for oboe, clarinet and string orchestra, Adagio for string orchestra - Malta Philharmonic Orchestra, Brian Schembri, conductor, Diego Dini Ciacci, oboe, Fabrizio Meloni, clarinet - CPO - 2016

- Ballet Music: Sextuor, Bric a Brac - Polish Radio Orchestra, Wojciech Michniewski, Lukasz Borowicz - conductors - Tansman Festival - CPO - 2017

- Kol Nidrei - Ensemble Choral Copernic, Itai Daniel, conductor, Sebastien Obrecht, tenor, Nicole Wiener, organ - Institut Europeen des Musiques Juives - 2018

- 11 Interludes, Hommage a Arthur Rubinstein, 2 Pieces hebraiques, Prelude et Toccata, 6 Caprices, Etude-studio - Giorgio Koukl, piano - Grand Piano - 2019

- The Polish Rhapsody - Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, Jacek Kasprzyk, conductor - The National Frederic Chopin Institute, NIFCCD - 2019

- Isaiah, The Prophet - Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Choir, Paul van Kempen, conductor, Cornelis Kalkman, tenor - Decca - 2020

- Danse de la Sorciere - Les solistes de l'Orchestre de Paris, Laurent Wagschal, piano - Indésens Records - 2020

- Musique de cour - Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, Ben Glassberg, conductor, Thibaut Garcia, guitar - Erato Records - 2020

References

- Guillot, Pierre (2000). Hommage au compositeur Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986). Paris: Presses de l'Universite de Paris-Sorbonne. ISBN 2-84050-175-9. ISSN 1275-2622.

- Schwerke, Irving (1931). Alexandre Tansman, compositeur polonais. Paris: Éditions Max Eschig.

- Jewish Records Indexing: Łódź

- Chana Tancman's Registration Card

- "Alexandre Tansman (Composer, Arranger) - Short Biography". www.bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- Hugon, Gerald (2000). Presentation du compositeur et de son oeuvre [in:] Hommage au compositeur Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986), textes réunis par Pierre Guillot. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne. ISBN 2-84050-175-9. ISSN 1275-2622.

- Cegiełła, Janusz (1986). Dziecko szczęścia. Aleksander Tansman i jego czasy [The Luck Child. Alexander Tansman and His Times]. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. ISBN 83-06-01256-9.

- Tansman, Alexandre (2013). Segond-Genovesi Cédric; Tansman Zanuttini Mireille; Tansman Martinozzi Marianne (eds.). Regards en arrière, Itinéraire d'un musicien cosmopolite au XXe siècle. Château-Gontier: Aedam Musicae. ISBN 978-2-919046-08-9.

- Hugon, Gerald (1995). Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986). Catalogue de l'oeuvre. Paris: Éditions Max Eschig.

- Slonimsky, Nicholas (2004). Writings on Music. Early Articles for the Boston Evening Transcript. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-97028-4.

- Korabelnikova, Ludmila (2008). Alexander Tcherepnin. The Saga of a Russian Emigré Composer. Bloomington - Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34938-5.

- Tansman, Alexandre (1948). Igor Stravinsky. Igor Stravinsky (first publication ed.). Amiot Dumont, Paris.

- "TANSMAN PHILHARMONIC". tansman.org.pl. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

- In 1929-1930, Tansman recorded five Mazurkas (nos. 1, 8, 10, 2, and 6) from his Book 1 - of 4 Mazurkas Books (1918-1941) - dedicated to Albert Roussel, for the Gramophone Company in France (6 March 1929, 3 March 1930, issued on two sides of 78rpm K6036).

- Cegiełła, Janusz (1996). Dziecko szczęścia. Aleksander Tansman i jego czasy [The Luck Child. Alexander Tansman and His Times]. 1–2. Łódź: 86 Press. ISBN 83-852387-3-5.

- Carpentier, Alejo (1986). A. Tansman y su obra luminosa, 1929 [in:] Obras completas de Alejo Carpentier. Mexico - Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno Editores. ISBN 968-23-1350-3.

- Wendland, Wojciech (2013). W 89 lat dookoła świata. Aleksander Tansman u źródeł kultury i tożsamości [Around the World in 89 Years. Alexander Tansman at the Sources of Culture and Identity]. Łódź: Astra Editions, Aleksander Tansman Association for the Promotion of Culture. ISBN 978-83-938620-0-9.

- Kaczynski, Tadeusz (2000). Entre la Pologne et la France [in:] Hommage au compositeur Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986), textes réunis par Pierre Guillot. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne. ISBN 2-84050-175-9. ISSN 1275-2622.

- "Aleksander Tansman". Polish Music Center. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Wendland, Andrzej (1996). Gitara w twórczości Aleksandra Tansmana [La guitare dans les œuvres d'Alexandre Tansman]. Łódź: Ars Longa Edition. ISBN 83-905532-0-1.

- Tansman, Marianne (2018). La Guitare dans la vie d'Alexandre Tansman. Lyon: Éditions Habanera. ISBN 978-2-9565816-0-4.

- "Musique concertante d'Alexandre Tansman". www.alexandre-tansman.com (in French). Retrieved 2021-02-01.

Sources

- Caroline Rae: "Alexandre Tansman". Grove Music Dictionary Online, ed. L Macy, accessed 21 Mar 05. (subscription access)

- Anne Girardot, Richard Langham Smith: "Alexandre Tansman". Grove Music Dictionary Online (OperaBase), ed. L Macy, accessed 21 Mar 05. (subscription access)

- Tansman competition biography - biographical sketch by J. Cegiella

- Polish Music Center - studies on A. Tansman's life and work, collections

- Tansman Philharmonic - dedicated to A. Tansman's heritage, a platform of artistic presentations, documents, interviews

- Irving Schwerke, Alexandre Tansman, compositeur polonais - the first monographic study on A. Tansman's work and its reception: 1931

- G. Hugon, Catalogue de l'oeuvre d'Alexandre Tansman - official Editor's catalogue of A. Tansman's works: 1995

- J. Cegiella, The Luck Child. Alexander Tansman and His Times - complete and critical biographical study on A. Tansman's life and work, (1897-1939): 1986; vol. 1-2 (1897-1986, including catalogue of A. Tansman's works, edited by A. Wendland): 1996

- Hommage au compositeur Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986), Paris-Sorbonne collection of studies on A. Tansman's biography, style, aesthetics and reception of his works, edited by P. Guillot: 2000

- A. Tansman, Regards en arrière. Itineraire d'un musicien - A. Tansman's diaries, memoirs, autobiography, documents, edited by C. Segond-Genovesi, M. Tansman Zanuttini, M. Tansman Martinozzi: 2013

External links

- Site officiel

- Tansman Philharmonic

- Alexander Tansman, Editions Durand Salabert Eschig

- Alexander Tansman, The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

- Alexander Tansman, Los Angeles Philharmonic

- Alexander Tansman, Polish Music Center, University of Southern California

- Alexander Tansman, Milken Archive

- Alexander Tansman, Institut Européen des Musiques Juives

- Alexander Tansman, Universität Hamburg Lexikon verfolgter Musiker

- Alexander Tansman, Musica et Memoria

- Alexander Tansman, Bach Cantatas

- Alexander Tansman, Naxos label recordings