Self-immolation

Self-immolation is the act of setting fire to oneself with a flammable liquid and willingly burning to death. It is typically used for political or religious reasons, often as a form of protest or in acts of martyrdom. It has a centuries-long recognition as the most extreme form of protest possible by humankind.

| Suicide |

|---|

Effects

The self-immolator first douse themself with a flammable liquid, such as petrol, before igniting themself with a match or a lighter. If the self-immolator wears more clothing, especially those made from natural fibres which are flammable, the fire will burn hotter and cause deeper burns. Self-immolators do not attempt to put out the fire by themselves or fight against it, hence it causes extensive burns.[1] Most of the time, it leads to amputation of extremities.[2] Self-immolation has been described as excruciatingly painful. Later the burns become severe, nerves are burnt and the self-immolator loses sensation at the burnt areas. Some self-immolators can die during the act from inhalation of toxic combustion products, hot air and flames.[3] A while later, their body releases adrenaline.

The body has an inflammatory response to burnt skin which happens after 25% is burnt in adults. This response leads to blood and body fluid loss. If the self-immolator is not taken to a burn centre in less than four hours, they are more likely to die from shock. If no more than 80% of their body area is burnt and the self-immolator is younger than 40 years old, there is a survival chance of 50%. If the self-immolator has over 80% burns, the survival rate drops to 20%.[2] Self-immolation survivors will have to cope with severe physical disfigurements and handicaps, as well as psychological trauma.

Etymology

The English word immolation originally meant (1534) "killing a sacrificial victim; sacrifice" and came to figuratively mean (1690) "destruction, especially by fire". Its etymology was from Latin immolare "to sprinkle with sacrificial meal (mola salsa); to sacrifice" in ancient Roman religion.

Self-immolation "setting oneself on fire, especially as a form of protest" was first recorded in Lady Morgan's France (1817).[4][5]

History

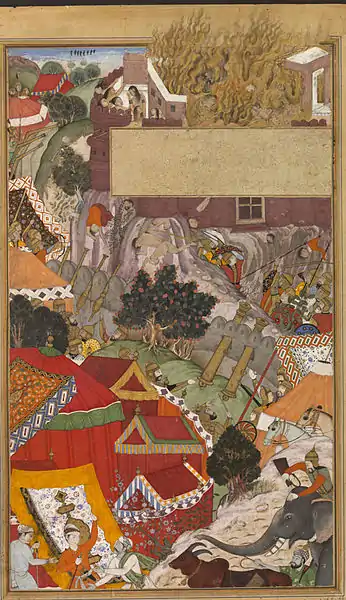

Self-immolation is tolerated by some elements of Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism, and it has been practiced for many centuries, especially in India, for various reasons, including jauhar, political protest, devotion, and renouncement. A historical example includes the practice of Sati when the Hindu goddess of the same name (see also Daksayani) legendarily set herself on fire after her father insulted her. Certain warrior cultures, such as those of the Charans and Rajputs, also practiced self-immolation.

Zarmanochegas was a monk of the Sramana tradition (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) who, according to ancient historians such as Strabo and Dio Cassius, met Nicholas of Damascus in Antioch around 22 BC and burnt himself to death in Athens shortly thereafter.[6][7]

The monk Fayu 法羽 (d. 396) carried out the earliest recorded Chinese self-immolation.[8] He first informed the "illegitimate" prince Yao Xu 姚緒—brother of Yao Chang who founded the non-Chinese Qiang state Later Qin (384–417)—that he intended to burn himself alive. Yao tried to dissuade Fayu, but he publicly swallowed incense chips, wrapped his body in oiled cloth, and chanted while setting fire to himself. The religious and lay witnesses were described as being "full of grief and admiration".

Following Fayu's example, many Buddhist monks and nuns have used self-immolation for political purposes. Based upon analysis of Chinese historical records from the 4th to the 20th centuries, some monks did offer their bodies in periods of relative prosperity and peace, but there is a "marked coincidence" between acts of self-immolation and times of crisis, especially when secular powers were hostile towards Buddhism.[9] For example, Daoxuan's (c. 667) Xu Gaoseng Zhuan(續高僧傳, or Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks) records five monastics who self-immolated on the Zhongnan Mountains in response to the 574–577 persecution of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou (known as the "Second Disaster of Wu").[10]

For many monks and laypeople in Chinese history, self-immolation was a form of Buddhist practice that modeled and expressed a particular path that led towards Buddhahood.[9]

Historian Jimmy Yu has stated that self-immolation cannot be interpreted based on Buddhist doctrine and beliefs alone but the practice must be understood in the larger context of the Chinese religious landscape. He examines many primary sources from the 16th and 17th century and demonstrates that bodily practices of self-harm, including self-immolation, was ritually performed not only by Buddhists but also by Daoists and literati officials who either exposed their naked body to the sun in a prolonged period of time as a form of self-sacrifice or burned themselves as a method of procuring rain.[11] In other words, self-immolation was a sanctioned part of Chinese culture that was public, scripted, and intelligible both to the person doing the act and to those who viewed and interpreted it, regardless of their various religion affiliations.

Although not done with fire, the Japanese ritual suicide seppuku (also called harakiri – ritual disembowelment) is another example of "self-immolation".

During the Great Schism of the Russian Church, entire villages of Old Believers burned themselves to death in an act known as "fire baptism" (self-burners: soshigateli).[12] Scattered instances of self-immolation have also been recorded by the Jesuit priests of France in the early 17th century. However, their practice of this was not intended to be fatal: they would burn certain parts of their bodies (limbs such as the forearm or the thigh) to symbolise the pain Jesus endured while upon the cross. A 1973 study by a prison doctor suggested that people who choose self-immolation as a form of suicide are more likely to be in a "disturbed state of consciousness", such as epilepsy.[13]

Political protest

Self-immolations are often public and political events that catch the attention of the news media through their dramatic means. They are seen as a type of altruistic suicide for a collective cause, and are not intended to inflict physical harm on others or cause material damage.[14] They attract attention to a cause and those who undergo the act are glorified in martyrdom. Self-immolation does not guarantee death for the burned.

The Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam saw the persecution of the country's majority religion under the administration of Catholic president Ngô Đình Diệm. Several Buddhist monks, including the most famous case of Thích Quảng Đức, immolated themselves in protest.

The example set by self-immolators in the mid 20th century did spark numerous similar acts between 1963 and 1971, most of which occurred in Asia and the United States in conjunction with protests opposing the Vietnam War. Researchers counted almost 100 self-immolations covered by The New York Times and The Times.[15] In 1968 the practice spread to the Soviet bloc with the self-immolation of Polish accountant and Armia Krajowa veteran Ryszard Siwiec, as well as those of two Czech students, Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc, and of toolmaker Evžen Plocek, in protest against the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. As a protest against Soviet rule in Lithuania, 19-year-old Romas Kalanta set himself on fire in Kaunas. In 1978 Ukrainian dissident and former political prisoner Oleksa Hirnyk burnt himself near the tomb of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko protesting against the russification of Ukraine under Soviet rule. In 2020, the practice resumed when Russian journalist Irina Slavina burned herself in Nizhny Novgorod after the last post on Facebook: "Russian Federation to be blamed for my death".[16]

The practice continues, notably in India: as many as 1,451 and 1,584 self-immolations were reported there in 2000 and 2001, respectively.[17] A particularly high wave of self-immolation in India was recorded in 1990 protesting the Reservation in India.[14] Tamil Nadu has the highest number of self-immolations in India to date.

In Iran, most self-immolations have been performed by citizens protesting the tempestuous changes brought upon after the Iranian Revolution. Many of which have gone largely unreported by regime authority, but have been discussed and documented by established witnesses. Provinces that were involved more intensively in postwar problems feature higher rates of self-immolation.[18] These undocumented demonstrations of protest are deliberated upon worldwide, by professionals such as Iranian historians who appear on international broadcasts such as Voice of America, and use the immolations as propaganda to direct criticism towards the Censorship in Iran. One specifically well documented self-immolation transpired in 1993, 14 years after the revolution, and was performed by Homa Darabi, a self-proclaimed political activist affiliated with the Nation Party of Iran. Darabi is known for her political self-immolation in protest to the compulsory hijab. Self-immolation protests continue to take place against the regime to this day. Most recently accounted for is the September 2019 Death of Sahar Khodayari, protesting a possible sentence of six months in prison for having tried to enter a public stadium to watch a football game, against the national ban against women at such events. One month after her death, Iranian women were allowed to attend a football match in Iran for the first time in 40 years.[19][20]

Since 2009, there have been, as of June 2017, 148 confirmed and two disputed[21][22] self-immolations by Tibetans, with most of these protests (some 80%) ending in death. The Dalai Lama has said he does not encourage the protests, but he has spoken with respect and compassion for those who engage in self-immolation. The Chinese government, however, claims that he and the exiled Tibetan government are inciting these acts.[23] In 2013, the Dalai Lama questioned the effectiveness of self-immolation as a demonstration tactic. He has also expressed that the Tibetans are acting of their own free will and stated that he is powerless to influence them to stop carrying out immolation as a form of protest.[24]

A wave of self-immolation suicides occurred in conjunction with the Arab Spring protests in the Middle East and North Africa, with at least 14 recorded incidents. These suicides assisted in inciting the Arab Spring, including the 2010–2011 Tunisian revolution, the main catalyst of which was the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, the 2011 Algerian protests (including many self-immolations in Algeria), and the 2011 Egyptian revolution. There have also been suicide protests in Saudi Arabia, Mauritania, and Syria.[25][26]

On 3 December 2020, a Taiwanese man self immolated to protest closure of Chinese CTi News.[27]

See also

References

- Santa Maria, Cara (9 April 2012). "Burn Care, Self-Immolation: Pain And Progress". Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Alpert, Emily (15 February 2012). "What happens after people set themselves on fire?". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "What does death by burning mean?". Tiden. 26 April 2003. Retrieved 22 January 2021 – via The Guardian.

- The Oxford English Dictionary, 2009, 2nd ed., v. 4.0, Oxford University Press.

- "immolate", Oxford Dictionaries.

- Strabo, xv, 1, on the immolation of the Sramana in Athens (Paragraph 73).

- Dio Cassius, liv, 9; see also Halkias, Georgios "The Self-immolation of Kalanos and other Luminous Encounters among Greeks and Indian Buddhists in the Hellenistic world". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, Vol. VIII, 2015: 163–186

- Benn (2007), 33–34.

- (2007), 199.

- Benn (2007), 80–82.

- Yu, Jimmy (2012), Sanctity and Self-Inflicted Violence in Chinese Religions, 1500–1700, Oxford University Press, 115–130.

- Coleman, Loren (2004). The Copycat Effect: How the Media and Popular Culture Trigger the Mayhem in Tomorrow's Headlines. New York: Paraview Pocket-Simon and Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 0-7434-8223-9.

- Prins, Herschel (2010). Offenders, Deviants or Patients?: Explorations in Clinical Criminology. Taylor & Francis. p. 291.

Topp ... suggested that such individuals ... have some capacity for splitting off feelings from consciousness. ... One imagines that shock and asphyxiation would probably occur within a very short space of time so that the severe pain ... would not have to be endured for too long.

- Biggs, Michael (2005). "Dying Without Killing: Self-Immolations, 1963–2002" (PDF). In Diego Gambetta (ed.). Making Sense of Suicide Missions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929797-9.

- Maris, Ronald W.; Alan Lee Berman; Morton M. Silverman; Bruce Michael Bongar (2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. Guilford Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- "Russian journalist dies after setting herself on fire following police search". the Guardian. Reuters. 2 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Coleman, Loren (2004). The Copycat Effect: How the Media and Popular Culture Trigger the Mayhem in Tomorrow's Headlines. New York: Paraview Pocket-Simon and Schuster. p. 66. ISBN 0-7434-8223-9.

- "National Library of Medicine: Self-immolation in Iran".

- "Iranian female football fan who self-immolated outside court dies: official".

- "Iran football: Women attend first match in decades".

- Free Tibet. "Tibetan Monk Dies After Self-Immolating in Eastern Tibet". Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Tibetan dies after self-immolation, reports say". Fox News. 21 July 2013.

- "Teenage monk sets himself on fire on 53rd anniversary of failed Tibetan uprising". The Telegraph. London. 13 March 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Dalai Lama doubts effect of Tibetan self-immolations". The Daily Telegraph. London. 13 June 2013.

- "Self-immolation spreads across Mideast inspiring protest".

- "Second Algerian dies from self-immolation: official".

- "Taiwanese man self immolates to protest closure of pro-China CTi News".

Bibliography

- King, Sallie B. (2000). They Who Burned Themselves for Peace: Quaker and Buddhist Self-Immolators during the Vietnam War, Buddhist-Christian Studies 20, 127–150 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Kovan, Martin (2013). Thresholds of Transcendence: Buddhist Self-immolation and Mahāyānist Absolute Altruism, Part One. Journal of Buddhist Ethiks 20, 775–812

- Kovan, Martin (2014). Thresholds of Transcendence: Buddhist Self-immolation and Mahāyānist Absolute Altruism, Part Two. Journal of Buddhist Ethiks 21, 384–430

- Patler, Nicholas. Norman's Triumph: the Transcendent Language of Self-Immolation Quaker History, Fall 2015,18–39.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Self-immolation. |