Set the Night on Fire

Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties is a best-selling book by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener about Los Angeles in the 1960s. The authors combine archival research and personal interviews with their own experiences in the civil rights and anti-war movements to tell the social history or, as the authors term it, "movement history"[lower-alpha 1] of this transformative decade.[1][2] The book's purpose is not to present a comprehensive history of 1960s Los Angeles but to dispel the mythology surrounding this era and replace it with the neglected history of the populist social and cultural movements that shifted power away from an entrenched elite and opened up opportunities for radical egalitarian change.[3]

Book Jacket | |

| Author | Mike Davis, Jon Wiener |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Ron Butler |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | History |

| Publisher | Verso Books (print), Audible Studios (audiobook) |

Publication date | 2020 (Hardcover, Kindle, and Audiobook) |

| Media type | Print, Kindle, Audiobook |

| Pages | 800pp., 25 hours and 25 minutes audio. |

| ISBN | 978-1784780227 |

| Website | Official book website, Set the Night on Fire at Verso Books. |

Mike Davis (born 1946) is an American writer, political activist, urban theorist, and historian. He is best known for his investigations of power and social class in his native Southern California. Jon Wiener (born 1944) is an American historian and journalist based in Los Angeles.

Synopsis

The book covers a period of more than ten years beginning at the start of the decade with a description of the Los Angeles of the 1950s and ending with the defeat of Sam Yorty, the powerful Los Angeles mayor by African American city councilman Tom Bradley. During the 1950s, Los Angeles became associated with images of laid-back surf culture, the beatniks, and the celebrity lifestyle; images of Hollywood and Venice Beach filled the minds of individuals when the city of Angeles was mentioned. But behind the scenes, the city was rife with corruption, police violence, and poverty, all while being under the tight control of police chief William H. Parker and Mayor Sam Yorty, who used their unchecked power to rule over the city. By the advent of the 1960s, the mythical image Los Angeles had carefully cultivated was beginning to crack, and the void which was created was filled by the counter-culture movements which would eventually define the decade.[4]

Set the Night on Fire covers a range of movements—the desegregation struggle, the gay rights movement, and the birth of the Black Power movement. The emergence of alternative media, and the stories of draft resisters, activist nuns and priests, and the high school "blowouts" during 1968 in Chicano East Los Angeles are some of the subjects explored. The authors make it clear their intention is not to retell another version of myths of the 1960s. They feel the story of Los Angeles is normally written from the perspective of the elite and wealthy individuals, usually white and male, and those they surrounded themselves with, and the history of Los Angeles has become the myth they projected onto it. Lost in this myth is the vast majority of Los Angeles: the normal working-class citizens and students, the black and brown faces, those marginalized by gender or sexual orientation. These are the individuals who make up the history of Los Angeles in Set the Night on Fire and their parallel and sometimes intersecting movements form its narrative.[1][5]

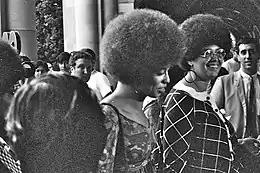

The Civil Rights Movement is the primary overall focus of the book. Chapters include essays on Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam (Chapter 4); the inequalities between White and minority communities (Chapters 5–7), with a special focus on the struggle against segregated housing; the roles played by the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Maulana Karenga and the US Organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the United Civil Rights Committee; the Watts Uprising and Watts Renaissance (Chapters 13 and 15); the story of Communist Party USA activist Angela Davis (Chapter 27); and the birth of the Chicanx movement in East Los Angeles (Chapters 31-32).[6][7]

The topics of the press and civil rights intersect in the Watts Uprising. The authors write about the collision:

It wasn't just the editorials in the Times; their reporters in Watts—all white, of course—emphasized the threat from "screaming" mobs of Black "wild men," who were reported to be shouting, "It's too late, white man. You had your chance. Now it's our turn"; "Next time you see us we'll be carrying guns"; and, "We have nothing to lose." The reporter concluded that the mood of Black people in the streets was "sickening." The Freep, for its part, published reports of the uprising written by Blacks—its most significant contribution. One, on the front page, described a corner where four cops were beating a Black man with billy clubs, as a Black crowd gathered, shouting, "Don't kill that man!" Then, "the crowd began to attack the officers." The cops told them, "Go home, niggers." The crowd grew; "The officers first attempted to fight but then ran away." In The Freep's reporting, the Blacks' target was not "whitey" in general; instead they were retaliating against particular LAPD officers who were acting particularly brutally."[lower-alpha 2][8]

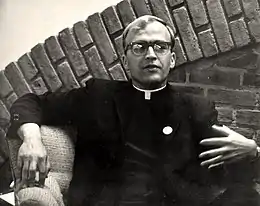

The struggle for women's rights and LGBT equality are covered. The story of police violence at the Black Cat Tavern in 1967 and the resulting burst of LGBT activism in Los Angeles,[7][5] the founding of The Advocate magazine and the Metropolitan Community Church are covered in Chapter 11, "Before Stonewall: Gay L.A (1964-1970)". While feminism is an ever-present theme in the book, it becomes the focus in chapter 33, "The Many Faces of Women's Liberation (1967-1974)" and the Los Angeles chapter of the National Organization for Women has a prominent place in the narrative, along with the subjects of equal pay and living wages, women's reproductive rights, child care, and prison rehabilitation. The special plight experienced by women of color has a presence throughout the book, but takes a special place here.[6] The subject of religion and its role in the civil rights movement is highlighted by the contrast and struggle between the Metropolitan Community Church, Sister Corita Kent, Father William DuBay, and Cardinal James Francis McIntyre.[5]

The book concludes by returning to the authors' thoughts at the beginning and a summary of the "unrealized hopes of the 1960s"—why the movements achieved what they did and why they failed to achieve all they had hoped to. Jerald Podair writes in the Los Angeles Review of Books,

But as the authors acknowledge, the unrealized hopes of the 1960s are also rooted in the incompatibilities and inconsistencies of the component parts of the movements themselves. Set the Night on Fire is filled with terrible ifs and might-have-beens. Perhaps the most heartbreaking was the inability of the African-American and Latino communities, each experiencing profound cultural and political change, to forge enduring alliances. As the authors ruefully conclude, 'One can only speculate about how L.A. history might have played out if the Southside and the Eastside had been able to build a common agenda'.[3]

Reviews

- Sean Dempsey (April 26, 2020). "Review: Exploring the radical politics of Los Angeles in the 1960's". America Magazine. The Jesuit Review. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Ben Ehrenreich (April 27, 2020). "Set the Night on Fire by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener review – the real LA in the 1960s". The Guardian. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Samuel Farber. "The Many Explosions of Los Angeles in the 1960s". Jacobin. Retrieved September 28, 2020.. "Mike Davis and Jon Wiener's chronicle of Los Angeles in the 1960s, Set the Night on Fire, isn't just a stunning portrait of a city in upheaval half a century ago. It's a history of uprisings for civil rights, against poverty, and for a better world that speaks directly to our current moment of mass protest."

- Dana Goodyear (April 24, 2020). "Mike Davis in the Age of Catastrophe". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Erik Himmelsbach-Weinstein (April 13, 2020). "Review: How L.A.'s '60s movements fought for justice — and sometimes even achieved it". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 28, 2020.. "The '60s are remembered as a perfect storm of rebellion, but our memories are often shaped by repetitive archival news footage tattooed onto our brains. "Set the Night on Fire" fills in many blanks, focusing mostly on the movements emerging from South and East L.A. — the struggle for fair housing, the fight to integrate schools and jobs — while also excavating the forgotten core of L.A. resistance, illuminating those who often took life-risking steps to expose injustice."

- Jerald Podair (April 14, 2020). "The Fire and the Fizzle". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Jeff Roquen (June 8, 2020). "Book Review: Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener". LSE US Centre. London School of Economics. Retrieved September 28, 2020.. "Beyond a chronicle of a metropolis or an era, Set the Night on Fire thoroughly illustrates the myriad dynamics of inequality, exposes the short- and long-term consequences of discrimination and offers hope in overcoming socio-economic divisions through unyielding activism for equal rights and equal justice"

- Lew Whittington (April 14, 2020). "Review: Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties". New York Journal of Books. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

Awards and recognition

- Set the Night on Fire was a Los Angeles Times Best Seller.[9]

See also

References

Notes

- Davis & Wiener, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, pp.12–18.

- Davis & Wiener, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, pp.177.

Citations

- Ben Ehrenreich (April 27, 2020). "Set the Night on Fire by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener review – the real LA in the 1960s". The Guardian. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

-

- Dana Goodyear (April 24, 2020). "Mike Davis in the Age of Catastrophe". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Jerald Podair (April 14, 2020). "The Fire and the Fizzle". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Lew Whittington (April 14, 2020). "Review: Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties". New York Journal of Books. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Samuel Farber. "The Many Explosions of Los Angeles in the 1960s". Jacobin. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Jeff Roquen. "Book Review: Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener". LSE US Centre. London School of Economics. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Erik Himmelsbach-Weinstein (April 13, 2020). "Review: How L.A.'s '60s movements fought for justice — and sometimes even achieved it". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- "Excerpt: Set the Night on Fire by Mike Davis, Jon Wiener". Los Angeles Review of Books. April 14, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- "Bestsellers List: June 14, 2020". The Los Angeles Times. The California Independent Booksellers Alliance. June 14, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

Further reading

- Brook, Vincent. (2013). Land of Smoke and Mirrors: A Cultural History of Los Angeles. Rutgers University Press

- Buntin, John. (2009). L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America's Most Seductive City.

- Davis, Mike (2006). City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. New York: Verso Books.

- Faderman, Lillian and Timmons, Stuart. (2006). Gay L. A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, And Lipstick Lesbians. New York: Basic Books.

- Horne, Gerald. (1995). Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960s.

- Keil, Roger. (1998). Los Angeles: Globalization, Urbanization, and Social Struggles.

- Klein, Norman M. and Schiesl, Martin J., eds. (1990). 20th Century Los Angeles: Power, Promotion, and Social Conflict.

- Nicolaides, Becky M. (2002). My Blue Heaven: Life and Politics in the Working-Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920–1965.

External links

- Set the Night on Fire at Verso Books.

- Set the Night on Fire at Penguin Random House.

- Interview with Mike Davis. The New Yorker.

- "Excerpt: Set the Night on Fire by Mike Davis, Jon Wiener". Los Angeles Review of Books. April 14, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Official book website.

- Jon Wiener, author website.