History of California before 1900

Human history in California began when indigenous Americans first arrived some 13,000 years ago. Coastal exploration by Spanish began in the 16th century, and settlement by Europeans along the coast and in the inland valleys began in the 18th century. California was ceded to the United States under the terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo following the defeat of Mexico in the Mexican–American War. American westward expansion intensified with the California Gold Rush, beginning in 1848. California joined the Union as a free state in 1850, due to the Compromise of 1850. By the end of the 19th century, California was still largely rural and agricultural, but had a population of about 1.4 million.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of California |

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

|

|

Native inhabitants

The most commonly accepted model of migration to the New World is that people from Asia crossed the Bering land bridge to the Americas some 16,500 years ago. The remains of Arlington Springs Man on Santa Rosa Island are among the traces of a very early habitation, dated to the Wisconsin glaciation (the most recent ice age) about 13,000 years ago.

In all, some 30 tribes or culture groups lived in what is now California, gathered into perhaps six different language family groups. These groups included the early-arriving Hokan family (winding up in the mountainous far north and the Colorado River basin in the south) and the later-arriving Uto-Aztecan of the desert southeast. This cultural diversity was among the densest in North America, and was likely the result of a series of migrations and invasions during the previous 13,000 years, and perhaps even earlier.[1]

At the time of the first European contact, Native American tribes in California included the Chumash, Nisenan, Maidu, Miwok, Modoc, Mohave, Ohlone, Pomo, Serrano, Shasta, Tataviam, Tongva, Wintu, Yurok, and Yokut. The relative strength of the tribes was dynamic, as the more successful expanded their territories and less successful tribes contracted. Slave-trading and war among tribes alternated with periods of relative peace. The total population of Native California is estimated, by the time of extensive European contact in the 18th century, to have been perhaps 300,000. Before Europeans landed in North America, about one-third of all natives in what is now the United States were living in the area that is now California.[2] California indigenous language diversity numbered 80 to 90 languages and dialects, some surviving to the present although endangered.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Tribes adapted to California's many climates. Coastal tribes were a major source of trading beads, which were produced from mussel shells and made using stone tools. Tribes in California's broad Central Valley and the surrounding foothills developed early agriculture, while tribes living in the mountains of the north and east relied heavily on salmon and game hunting, and collected and shaped obsidian for themselves and trade. The harsh deserts of the southeast were home to tribes who learned to thrive by making careful use of local plants and by living in oases or along water courses. Local trade between indigenous populations enabled them to acquire seasonings such as salt, or foodstuffs and other goods that might be rare in certain locales, such as flint or obsidian for making spear and arrow points.

The Native Americans had no domesticated animals except dogs, no pottery; their tools were made out of wood, leather, woven baskets and netting, stone, and antler. Some shelters were made of branches and mud; some dwellings were built by digging into the ground two to three feet and then building a brush shelter on top covered with animal skins, tules and/or mud.[4] On the coast and somewhat inland traditional architecture consists of rectangular redwood or cedar plank semisubterranean houses. Traditional clothing was minimal in the summer, with tanned deerhide and other animal leathers and furs and coarse woven articles of grass clothing used in winter. Feathers were sewn into prayer pieces worn for ceremonies. Basket weaving was a high form of art and utility, as were canoe making and other carving. Some tribes around Santa Barbara, California, and the Channel Islands were using large plank canoes to fish and trade, while tribes in the California delta and San Francisco Bay Area were using tule canoes and some tribes on the Northwest coast carved redwood dugout canoes.[4]

A dietary staple for most indigenous populations in interior California was acorns, which were dried, shelled, ground to flour, soaked in water to leach out their tannin, and cooked. The grinding holes worn into large rocks over centuries of use are still visible in many rocks today.[5] The ground and leached acorn flour was usually cooked into a nutritious mush, eaten daily with other traditional foods. Acorn preparation was a very labor-intensive process nearly always done by women. There are estimates that some indigenous populations might have eaten as much as one ton of acorns in one year.[6] Families tended productive oak and tanoak groves for generations. Acorns were gathered in large quantities, and could be stored for a reliable winter food source.[7]

The staple foods then used by other indigenous American tribes, corn and/or potatoes, would not grow without irrigation in the typically short three- to five-month wet season and nine- to seven-month dry seasons of California (see Mediterranean climate). Despite this, the natural abundance of California, and the environmental management techniques developed by California tribes over millennia, allowed for the highest population density in the Americas north of Mexico.[8] The indigenous people practiced various forms of forest gardening in the forests, grasslands, mixed woodlands, and wetlands, ensuring that desired food and medicine plants continued to be available. The Native Americans controlled fire on a regional scale to create a low-intensity fire ecology which prevented larger, catastrophic fires and sustained a low-density "wild" agriculture in loose rotation.[9][10][11][12] By burning underbrush and grass, the Native Americans revitalized patches of land whose regrowth provided fresh shoots to attract food animals. A form of fire-stick farming was used to clear areas of old growth, which in turn encouraged new growth, in a repeated cycle; a primitive permaculture.[11]

The high and rugged Sierra Nevada mountains located behind the Great Basin Desert east of California, extensive forests and mountains in the north, the rugged and harsh Sonoran Desert and Mojave Desert in the south and the Pacific Ocean on the west effectively isolated California from easy trade or tribal interactions with indigenous populations on the rest of the continent, and delayed the tragedies and damages of colonial-settler arrival until the Spanish missions, the Gold Rush, and the Euro-American invasion of indigenous Californians' territories.

European exploration (1530–1765)

The first European explorers, flying the flags of Spain and of England, sailed along the coast of California from the early 16th century to the mid-18th century, but no European settlements were established. The most important colonial power, Spain, focused attention on its imperial centers in Mexico and Peru. Confident of Spanish claims to all lands touching the Pacific Ocean (including California), Spain sent an exploring party sailing along the California coastline. The California seen by these ship-bound explorers was one of hilly grasslands and wooded canyons, with few apparent resources or natural ports to attract colonists. The other European nations, with their attentions focused elsewhere, paid little attention to California. It was not until the middle of the 18th century that both Russian and British explorers and fur traders began establishing trading stations on the coast.

Hernán Cortés

Around 1530, Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán (president of New Spain) was told by an Indian slave of the Seven Cities of Cibola that had streets paved with gold and silver. About the same time Hernán Cortés was attracted by stories of a wonderful country far to the northwest, populated by Amazonish women and abounding with gold, pearls and gems. The Spaniards conjectured that these places may be one and the same.

An expedition in 1533 discovered a bay, most likely that of La Paz, before experiencing difficulties and returning. Cortés accompanied expeditions in 1534 and 1535 without finding the sought-after city.

On May 3, 1535, Cortés claimed "Santa Cruz Island" (now known as the Baja California Peninsula) and laid out and founded the city that was to become La Paz later that spring.

Francisco de Ulloa

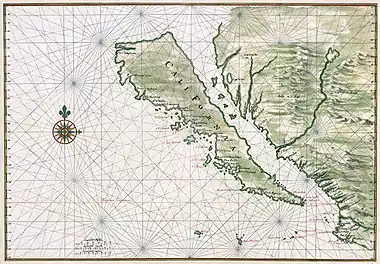

In July 1539, Cortés sent Francisco de Ulloa to sail the Gulf of California with three small vessels. He made it to the mouth of the Colorado River, then sailed around the peninsula as far as Cedros Island.[13][14] This proved that Baja California is a peninsula.[15] The next year, an expedition under Hernando de Alarcón ascended the lower Colorado River to confirm Ulloa's finding. Alarcón may thus have become the first to reach Alta California.[16] European maps published subsequently during the 16th century, including those by Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius, correctly depict Baja California as a peninsula, although some as late as the 18th century do not.

The account of Ulloa's voyage marks the first-recorded application of the name "California". It can be traced to the fifth volume of a chivalric romance, Amadis de Gallia, arranged by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo and first printed around 1510, in which a character travels through an island called "California".[17]

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo is believed to be the first European to explore the California coast. He was either of Portuguese or Spanish background, although his origins remain unclear. He was a soldier, crossbowman, and navigator who sailed for the Spanish Crown. In June 1542 Cabrillo led an expedition in two ships of his own design and construction from the west coast of what is now Mexico. He landed on September 28 at San Diego Bay,[18] claiming what he thought was the Island of California for Spain. Californias' channel islands lie offshore from Baja California to northern California, and Cabrillo named each of the channel islands as he passed and claimed them for Spain.

Cabrillo and his crew continued north and came ashore October 8 at San Pedro bay, later to become the port of Los Angeles, which he originally named the bay of smoke (bahia de los fumos) due to the many cooking fires of the native Chumash Indians along the shore. The expedition then continued north in an attempt to discover a supposed coastal route to the mainland of Asia. Cabrillo sailed at least as far north as San Miguel Island,[18] may have gone as far north as Point Reyes (north of San Francisco), but died as the result of an accident during this voyage; the remainder of the expedition, which may have reached as far north as the Rogue River in today's southern Oregon, was led by Bartolomé Ferrer.[19]

Cabrillo and his men found that there was essentially nothing for the Spanish to easily exploit in California, located at the extreme limits of exploration and trade from Spain. The expedition depicted the indigenous populations as living at a subsistence level, typically located in small rancherias of extended family groups of 100 to 150 people.

Opening of Spanish–Philippine trading route (1565)

In 1565, the Spanish developed a trading route where they took gold and silver from the Americas and traded it for goods and spices from China and other Asian areas. The Spanish set up their main base in Manila in the Philippines.[20][21] The trade with Mexico involved an annual passage of galleons. The Eastbound galleons first went north to about 40 degrees latitude and then turned east to use the westerly trade winds and currents. These galleons, after crossing most of the Pacific Ocean, would arrive off the California coast 60 to over 120 days later, near Cape Mendocino, about 300 miles (480 km) north of San Francisco, at about 40 degrees N. latitude. They could then sail south down the California coast, utilizing the available winds and the south-flowing California Current, about 1 mi/hr (1.6 km/h). After sailing about 1,500 miles (2,400 km) south on they eventually reached their home port in Mexico.

The first Asians to set foot on what would be the United States occurred in 1587, when Filipino sailors arrived in Spanish ships at Morro Bay.[22][23]

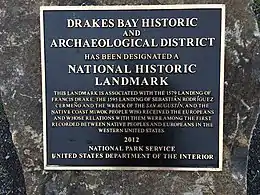

Sir Francis Drake

After successfully sacking Spanish colonial settlements and plundering Spanish treasure ships along their Pacific coast colonies in the Americas, English privateer and explorer Francis Drake sailed into Oregon,[24] before exploring and claiming an undefined portion of the California coast in 1579, landing north of the future city of San Francisco, perhaps at Point Reyes (on June 17).[25] He had friendly relations with the Coast Miwok and claimed sovereignty of the area for England as Nova Albion, or New Albion.[26]

Sebastián Vizcaíno

In 1602, the Spaniard Sebastián Vizcaíno explored California's coastline on behalf of New Spain from San Diego as far north as Cape Mendocino.[27] He named San Diego Bay, and also put ashore in Monterey, California. He ventured inland south along the coast and recorded a visit to what is likely Carmel Bay. His major contributions to the state's history were the glowing reports of the Monterey area as an anchorage and as land suitable for settlement and growing crops, as well as the detailed charts he made of the coastal waters (which were used for nearly 200 years).[28]

Further European ventures (1765–1821)

Spanish ships plying the China trade probably stopped in California every year after 1680. Between 1680 and 1740, Spanish merchants out of Mexico City financed thriving trade between Manila, Acapulco and Callao. In Manila, they picked up cotton from India and silks from China. The Spanish Crown viewed too much imported Asian cloth to Mexico and Lima as a competitive threat to the Spanish American markets for cloth produced in Spain, and as a result, restricted the tonnage permitted on the ships from Manila to Acapulco. Mexico City merchants in retaliation overstuffed the ships, even using the space for water to carry additional contraband cargo. As a result, the ships coming from Manila had enough water for two months, but the trip took four to six months. (Hawaii was unknown to the Spanish navigators). The sea currents take ships sailing from Manila to Acapulco up north, so that they first touch land at San Francisco or Monterey, in what is now California.[29][30] In the mid-18th century, tensions were brewing between Great Britain and Spain. In 1762, while the two nations were at war, Britain captured Manila in the Pacific and Havana in the Atlantic. This was probably a stimulus for Spain to build presidios at San Francisco and Monterey in 1769. The British, too, stepped up their activities in the Pacific. British seafaring Captain James Cook, midway through his third and final voyage of exploration in 1778, sailed along the west coast of North America aboard HMS Resolution, mapping the coast from California all the way to the Bering Strait. In 1786 Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, led a group of scientists and artists on a voyage of exploration ordered by Louis XVI and were welcomed in Monterey. They compiled an account of the Californian mission system, the land and the people. Traders, whalers and scientific missions followed in the next decades.[31]

Spanish colonization and governance (1697–1821)

In 1697, the Viceroy Duque de Linares along with the Conde de Miravalle (180) and the treasurer of Acapulco (Pedro Gil de la Sierpe) financed Jesuit expansion into California. The Duque de Linares lobbied the Spanish Crown in 1711 to increase trade between Asia, Acapulco and Lima.[32] It is possible that Baja California Sur was used as a stopping point for unloading contraband on the way back from Manila to Acapulco. The contraband might then have been shipped across the Gulf of California to enter mainland Mexico by way of Sonora, where the Jesuits also had missions and sympathies for their financial backers.

In 1697, the Jesuit missionary Juan María de Salvatierra established Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, the first permanent mission on the Baja California Peninsula.[33] Spanish control over the peninsula, including missions, was gradually extended, first in the region around Loreto, then to the south in the Cape region, and finally to the north across the northern boundary of present-day Baja California Sur. A total of 30 Spanish missions in Baja California were established.

During the last quarter of the 18th century, the first Spanish settlements were established in what later became the Las Californias Province of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Reacting to interest by the Russians and, later, the British in the fur-bearing animals of the Pacific north coast, Spain further extended the series of Catholic missions, accompanied by troops and establishing ranches, along the southern and central coast of California. These missions were intended to demonstrate the claim of the Spanish Empire to what is now California. By 1823, 21 Spanish missions had been established in Alta California. Operations were based out of the naval base at San Blas and included not only the establishment and supply of missions in California, but a series of exploration expeditions to the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

The first quarter of the 19th century showed the continuation of the slow colonization of the southern and central California coast by Spanish missionaries, ranchers and troops. By 1820 Spanish influence was marked by the chain of missions reaching from Loreto, north to San Diego, to just north of today's San Francisco Bay Area, and extended inland approximately 25 to 50 miles (40 to 80 km) from the missions. Outside of this zone, perhaps 200,000 to 250,000 Native Americans were continuing to lead traditional lives. The Adams–Onís Treaty, signed in 1819, set the northern boundary of the Spanish claims at the 42nd parallel, effectively creating today's northern boundary between California and Oregon.

First Spanish colonies

Spain had maintained a number of missions and presidios in New Spain since 1519. The Crown laid claim to the north coastal provinces of California in 1542. Excluding Santa Fe in New Mexico, settlement of northern New Spain was slow for the next 155 years. Settlements in Loreto, Baja California Sur, were established in 1697, but it was not until the threat of incursion by Russian fur traders and potentially settlers, coming down from Alaska in 1765, that Spain, under King Charles III, felt development of more northern installations was necessary.

By then, the Spanish Empire was engaged in the political aftermath of the Seven Years' War, and colonial priorities in far away California afforded only a minimal effort. Alta California was to be settled by Franciscan Friars, protected by troops in the California missions. Between 1774 and 1791, the Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to further explore and settle Alta California and the Pacific Northwest.

Portolá expedition

In May 1768, the Spanish Inspector General (Visitador) José de Gálvez planned a four-prong expedition to settle Alta California, two by sea and two by land, which Gaspar de Portolá volunteered to command.

The Portolá land expedition arrived at the site of present-day San Diego on June 29, 1769, where it established the Presidio of San Diego and annexed the adjacent Kumeyaay village of Kosa'aay, making San Diego the first European settlement in the present state of California. Eager to press on to Monterey Bay, de Portolá and his group, consisting of Father Juan Crespí, 63 leather-jacket soldiers and a hundred mules, headed north on July 14. They reached the present-day site of Los Angeles on August 2, Santa Monica on August 3, Santa Barbara on August 19, San Simeon on September 13, and the mouth of the Salinas River on October 1. Although they were looking for Monterey Bay, the group failed to recognize it when they reached it.

On October 31, de Portolá's explorers became the first Europeans known to view San Francisco Bay. Ironically, the Manila Galleons had sailed along this coast for almost 200 years by then, without noticing the bay. The group returned to San Diego in 1770.

De Portolá was the first governor of Las Californias.

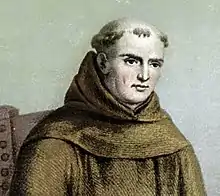

Junípero Serra

Junípero Serra was a Majorcan Franciscan who founded the first Alta California Spanish missions. After King Carlos III ordered the Jesuits expelled from New Spain on February 3, 1768, Serra was named "Father Presidente".

Serra founded San Diego de Alcalá in 1769. Later that year, Serra, Governor de Portolá and a small group of men moved north, up the Pacific Coast. They reached Monterey in 1770, where Serra founded the second Alta California mission, San Carlos Borromeo.

Alta California missions

The California missions comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans, to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans. Eighty percent of the financing of Spain's California program went not to missions but rather to the military garrisons established to keep the three great Pacific Ports of San Diego, Monterey and San Francisco under Spanish control; the Santa Barbara presidio on the Channel was constructed later. The missions introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, agricultural industry, along with invasive species of plants into the California regions. It is widely believe in California that the labor supply for the missions was supplied by the forcible relocation of the Native Americans and keeping them in peonage.[34] However, more recent scholarship suggests that the tiny number of Spaniards at each mission relied more upon negotiation, enticement and the threat of force to control the estimated 5,000 Indians typically surrounding what would become a mission. The missionaries and military were often at cross purposes in their vision of what California could become, and the missionaries preferred to rely upon Indian allies to maintain control. [35]

Most missions became enormous in terms of land area (approximately the size of modern counties in California), and yet the Spanish and Mexican staff was small, with normally two Franciscans and six to eight soldiers in residence. The size of the Indian congregations would grow from a handful at the founding to perhaps two thousand by the end of the Spanish period (1810). All of these buildings were built largely by the native people, under Franciscan supervision. Again, there is controversy in the literature as to whether the labor was forced. Production on missions between 1769 and 1810 was distributed primarily among the Indian congregation. However, in 1810, the California missions and presidios lost their financing as the Spanish Empire collapsed from Buenos Aires to San Francisco, as a result of the imprisonment of King Fernando VII in 1808 by the French. In this context, Indians came under increased pressure to produce, and the missions exported the produce of Indian labor via Anglo-American and Mexican merchants. Whether the proceeds were distributed to Indians or to local military men came increasingly to depend on the political skill and dedication of the individual missionaries. In 1825, independent Mexico finally send a governor to take control of California, but he arrived without adequate payroll for the military. In 1825, the use of uncompensated Indian labor at missions to finance Mexican presidios in California became normalized.[36]

In addition to the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown in an attempt to consolidate its colonial territories. None of these missions were completely self-supporting, requiring continued (albeit modest) financial support.

Starting with the onset of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810, this support largely disappeared, and the missions and their converts were left on their own. By 1827, the Mexican government passed the General Law of Expulsion, which exiled Spanish-born people, decimating the clergy in California. Some of the missions were then nationalized by the Mexican government and sold off. It was not until after statehood that the US Supreme Court restored some missions to the orders that owned them.

In order to facilitate overland travel, the mission settlements were situated approximately 30 miles (48 km) apart, so that they were separated by one day's long ride on horseback along the 600-mile-long (970 km) el Camino Real, Spanish for "the Royal Road", though often referred to today as the "King's Highway", and also known as the "California Mission Trail". Tradition has it that the padres sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail in order to mark it with bright yellow flowers. Later El Camino Viejo, another more direct route from Los Angeles to Mission San José and San Francisco Bay, developed along the western edge of the San Joaquin Valley.[37][38] Heavy freight movement over long distances was practical only via water, but soldiers, settlers and other travelers and merchandise on horses, mules, or carretas (ox carts), and herds of animals used these routes.

Four presidios, strategically placed along the California coast and organized into separate military districts, served to protect the missions and other Spanish settlements in Upper California.

A number of mission structures survive today or have been rebuilt, and many have congregations established since the beginning of the 20th century. The highway and missions became for many a romantic symbol of an idyllic and peaceful past. The Mission Revival style was an architectural movement that drew its inspiration from this idealized view of California's past.

Ranchos

The Spanish encouraged settlement with large land grants called ranchos, where cattle and sheep were raised. The California missions were secularized following Mexican independence, with the passing of the Mexican secularization act of 1833 and the division of the extensive former mission lands into more ranchos. Cow hides (at roughly $1 each) and fat (known as tallow, used to make candles as well as soaps) were the primary exports of California until the mid-19th century. This California hide trade involved large quantities of hides shipped nationally and internationally.

The rancho workers were primarily Native Americans, many of them former residents of the missions who had learned to speak Spanish and ride horses. Some ranchos, such as Rancho El Escorpión and Rancho Little Temecula, were land grants directly to Native Americans.

Administrative divisions

In 1773 a boundary between the Baja California missions (whose control had been passed to the Dominicans) and the Franciscan missions of Alta California was set by Francisco Palóu. Due to the growth of the Hispanic population in Alta California by 1804, the province of Las Californias, then a part of the Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces, was divided into two separate territorial administrations following Palóu's division between the Dominican and Franciscan missions. Governor Diego de Borica is credited with defining Alta California and Baja California's official borders.[39] The Baja California Peninsula became the territory of Baja California ("Lower California"), also referred to at times as Vieja California ("Old California"). The northern part became Alta California, also alternatively called Nueva California ("New California"). Because the eastern boundaries of Alta California Province were not defined, it included Nevada, Utah and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. The province bordered on the east with the Spanish settlements in Arizona and the province of Nuevo México, with the Sierra Nevada or Colorado River serving as the de facto border.[40]

Russian colonization (1812-1841)

Part of Spain's motivation to settle upper Las Californias was to forestall Russian colonization of the region. In the early 19th century, fur trappers with the Russian-American Company of Imperial Russia explored down the West Coast from trading settlements in Alaska, hunting for sea otter pelts as far south as San Diego. In August 1812, the Russian-American Company set up a fortified trading post at Fort Ross, near present-day Bodega Bay on the Sonoma Coast of Northern California, 60 miles (97 km) north of San Francisco on land claimed, but not occupied, by the British Empire. This colony was active until the Russians departed in 1839.[41]

In 1836 El Presidio de Sonoma, or "Sonoma Barracks", was established by General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, the Comandante of the northern frontier of Alta California. It was established as a part of Mexico's strategy to halt Russian incursions into the region, as the Mission San Francisco de Solano (Sonoma Mission) was for the Spanish.

Mexican Alta California (1821–1846)

First Mexican Empire and the First Mexican Republic

Substantial changes occurred during the second quarter of the 19th century. By 1809, Spain no longer governed California because the Spanish king was imprisoned by the French. For the next decade and a half, the colony came to rely upon trade with Anglo-Americans and Spanish-Americans from Lima and San Blas for economic survival and political news. The victory in the Mexican War of Independence from Spain in 1821 marked the beginning of Mexican rule in California, in theory, though in practice the First Mexican Empire did during its reign. The Indian congregations at missions and the missionaries provided the critical source of products that underlay export revenues for the entire colony between 1810 and 1825. Converting new Indians faded, while ranching and trade increased.

As the successor state to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, Mexico automatically included the provinces of Alta California and Baja California as territories. With the establishment of a republican government in 1823, Alta California, like many northern territories, was not recognized as one of the constituent states of Mexico because of its small population. The 1824 Constitution of Mexico refers to Alta California as a "territory". Independent Mexico came into existence in 1821, yet did not send a governor to California until 1825 First Mexican Republic, when José María de Echeandía brought the spirit of republican government and mestizo liberation to the frontier. Echeandia began the moves to emancipate Indians from missions, and to also liberate the profit motive among soldiers who were granted ranches where they utilized Indian labor. Pressure grew to abolish missions, which prevented private soldiers from extending their control over the most fertile land which was tilled by the Indian congregations. By 1829, the most powerful missionaries had been removed from the scene: Luis Martinez of San Luis Obispo, and Peyri of Mission San Luis Rey. The Mexican Congress had passed the General Law of Expulsion in 1827. This law declared all persons born in Spain to be "illegal immigrants" and ordered them to leave the new country of Mexico. Many of the missionary clergy were Spanish and aging, and gave in to the pressure to leave.

In 1831 a small group made up of the more wealthy citizens of Alta California got together and petitioned Governor Manuel Victoria asking for democratic reforms. The previous governor, José María de Echeandía, was more popular, so the leading wealthy citizens suggested to Echeandía that Victoria's stay as governor would be coming to an abrupt end soon. They built up a small army, marched into Los Angeles, and "captured" the town. Victoria gathered a small army and went to fight the upstart army, leading it himself. He met the opposing army on December 5, 1831, at Cahuenga Pass. In the Battle of Cahuenga Pass Victoria was wounded and resigned the governorship of Alta California. The previous governor, Echeandía, took the job, which he did until José Figueroa took over in 1833.

Next, the Mexican Congress passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the very first to feel the effects of this legislation the following year. The military received legal permission to distribute the Indian congregations' land amongst themselves in 1834 with secularization. Some aging Franciscans never abandoned the missions, such as Zalvidea of San Juan Capistrano. From Spain, Peyri regretted that he had departed.

Las Californias under the Centralist Republic of Mexico

In 1836, Mexico repealed the 1824 federalist constitution and adopted a more centralist political organization (under the Siete Leyes) that reunited Alta and Baja California in a single California Department (Departamento de las Californias). The change, however, had little practical effect in far-off Alta California. The capital of Alta California remained Monterey, as it had been since the 1769 Portola expedition first established an Alta California government, and the local political structures were unchanged.

In September 1835, Nicolás Gutiérrez was appointed as interim governor of California in January 1836, to be replaced by Mariano Chico in April, but he was very unpopular. Thinking a revolt was coming, Chico returned to Mexico to gather troops, but was reprimanded for leaving his post. Gutierrez, the military commandant, re-assumed the governorship, but he too was unpopular. Senior members of Alta California's legislature Juan Bautista Alvarado and José Castro, with support from Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, Comandante of the Fourth Military District and Director of Colonization of the Northern Frontier, and assistance from a group of Americans led by Isaac Graham, staged a revolt in November 1836 and forced Gutierrez to relinquish power. The Americans wanted Californian independence, but Alvarado instead preferred staying part of Mexico, albeit with greater autonomy.

In 1840, Graham allegedly began agitating for a Texas-style revolution in California, in March issuing a notice for a planned horse race that was loosely construed into being a plot for revolt. Alvarado notified Vallejo of the situation, and in April the Californian military began arresting American and English immigrants, eventually detaining about 100 in the Presidio of Monterey. At the time, there were fewer than 400 foreigners from all nations in the department. Vallejo returned to Monterey and ordered Castro to take 47 of the prisoners to San Blas by ship, to be deported to their home countries. Under pressure from American and British diplomats, President Anastasio Bustamante released the remaining prisoners and began a court-martial against Castro. Also assisting in the release of those caught up in the Graham Affair was American traveler Thomas J. Farnham.[42] In 1841, Graham and 18 of his associates returned to Monterey, with new passports issued by the Mexican federal government.

Also in 1841, political leaders in the United States were declaring their doctrine of Manifest Destiny, and Californios grew increasingly concerned over their intentions. Vallejo conferred with Castro and Alvarado recommending that Mexico send military reinforcements to enforce their military control of California.

In response, Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna sent Brigadier General Manuel Micheltorena and 300 men to California in January 1842. Micheltorena was to assume the governorship and the position of commandant general. In October, before Micheltorena reached Monterey, American Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones mistakenly thought that war had broken out between the United States and Mexico. He sailed into Monterey Bay and demanded the surrender of the Presidio of Monterey. Micheltorena's force was still in the south, and the Monterey presidio was undermanned. As such, Alvarado reluctantly surrendered, and retired to Rancho El Alisal. The next day Commodore Jones learned of his mistake, but Alvarado declined to return and instead referred the commodore to Micheltorena.

Micheltorena eventually made it to Monterey, but was unable to control his troops, a number of whom were convicts. This fomented rumors of a revolt, and by 1844, Alvarado himself became associated with the malcontents and an order was given by Micheltorena for his arrest. His detention, however, was short-lived as Micheltorena was under orders to organize a large contingent in preparation for war against the United States. All hands would be required for the task at hand.

This turned out to backfire on him, as on November 14, 1844, a group of Californios led by Manuel Castro revolted against Mexican authority. José Castro and Alvarado commanded the troops. There was no actual fighting, however; a truce was negotiated and Micheltorena agreed to dismiss his convict troops. However, Micheltorena reneged on the deal and fighting broke out this time. The rebels won the Battle of Providencia in February 1845 at the Los Angeles River and Micheltorena and his troops left California.

Pío Pico was installed as governor in Los Angeles, and José Castro became commandant general. Later, Alvarado was elected to the Mexican Congress. He prepared to move to Mexico City, but Pico declined funding for the transfer, and relations between the northern part of Alta California, with the increased presence of Americans, and the southern part, where the Spanish-speaking Californios dominated, became more tense.

John C. Frémont arrived in Monterey at the beginning of 1846. Afraid of foreign aggression, Castro assembled his militia, with Alvarado second in command, but Frémont went north to Oregon instead. An unstable political situation in Mexico strained relations among the Californios, and it seemed that civil war would break out between north and south.

By 1846, Alta California had a Spanish-speaking population of under 10,000, tiny even compared to the sparse population of states in the rest of northern Mexico. The Californios consisted of about 800 families, mostly concentrated on large ranchos. About 1,300 American citizens and a very mixed group of about 500 Europeans, scattered mostly from Monterey to Sacramento, dominated trading as the Californios dominated ranching. In terms of adult males, the two groups were about equal, but the American citizens were more recent arrivals.

Russian-American Company and Fort Ross

The Russian-American Company established Fort Ross in 1812 as its southernmost colony in North America, intended to provide Russian posts farther north with agricultural goods. When this need was filled by a deal between the RAC and the Hudson's Bay Company for produce from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River and other installations, the fort's intent was derailed, although it remained in Russian hands until 1841, and for the duration had a small population of Russians and other nationalities from the Russian Empire.

In 1814, Aleuts and Russian fur traders from Russian Alaska sailed to San Nicolas Island in search of sea otter and seal. After receiving complaints over excessive poaching in the waters around the island, the Aleuts and Russians killed most of the Native Nicoleño men as well as raping most of the women on the island, making the incident one of the earliest genocides of Native Californian tribes to come.

Outside influences

In this period, American and European traders began entering California in search of beaver. Using the Siskiyou Trail, Old Spanish Trail, and later, the California Trail, these trading parties arrived in California, often without the knowledge or approval of the Mexican authorities, and laid the foundation for the arrival of later Gold Rush-era Forty-Niners, farmers and ranchers.

In 1840, the American adventurer, writer and lawyer Richard Henry Dana, Jr., wrote of his experiences aboard ship off California in the 1830s in Two Years Before the Mast.[43]

The leader of a French scientific expedition to California, Eugène Duflot de Mofras, wrote in 1840, "...it is evident that California will belong to whatever nation chooses to send there a man-of-war and two hundred men."[44][45] In 1841, General Vallejo wrote Governor Alvarado that "...there is no doubt that France is intriguing to become mistress of California", but a series of troubled French governments did not uphold French interests in the area. During disagreements with Mexicans, the German-Swiss francophile John Sutter threatened to raise the French flag over California and place himself and his settlement, New Helvetia, under French protection.

American interest and immigrants

Although a small number of American traders and trappers had lived in California since the early 1830s, the first organized overland party of American immigrants was the Bartleson–Bidwell Party of 1841. With mules and on foot, this pioneering group groped its way across the continent using the still untested California Trail.[46] Also in 1841, an overland exploratory party of the United States Exploring Expedition came down the Siskiyou Trail from the Pacific Northwest. In 1844, Caleb Greenwood guided the Stephens–Townsend–Murphy Party, the first settlers to take wagons over the Sierra Nevada. In 1846, the misfortunes of the Donner Party earned notoriety as they struggled to enter California.

California Republic and the Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

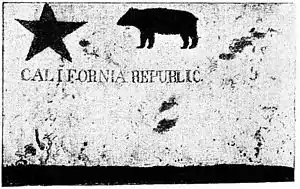

Bear Flag Revolt and the California Republic

After the United States declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846, it took almost two months (mid-July 1846) for definite word of war to get to California. Upon hearing rumors of war, U.S. consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed in Monterey, tried to keep peace between the Americans and the small Mexican military garrison commanded by José Castro. American army captain John C. Frémont, with about 60 well-armed men, had entered California in December 1845 and was making a slow march to Oregon when they received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent.[47]

On June 15, 1846, some 30 non-Mexican settlers, mostly Americans, staged a revolt, seized the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma, and captured Mexican general Mariano Vallejo. They raised the "Bear Flag" of the California Republic over Sonoma. The so-called California Republic lasted one week, with William B. Ide as its president, until Frémont arrived with his U.S. army detachment and took over military command on June 23. The California state flag today is based on the original Bear Flag, and continues to contain the words "California Republic".

American Conquest

Commodore John Drake Sloat, on hearing of imminent war and the revolt in Sonoma, landed and occupied Monterey. Sloat next ordered his naval forces to occupy Yerba Buena (present San Francisco) on July 7 and raise the American flag. On July 23, Sloat transferred his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton. Commodore Stockton put Frémont's forces under his command. Frémont's "California Battalion" swelled to about 160 men with the addition of volunteers recruited from American settlements, and on July 19 he entered Monterey in a joint operation with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The official word had been received — the Mexican–American War was on. The U.S. naval forces (which included U.S. Marines) easily took over the north of California; within days, they controlled Monterey, Yerba Buena, Sonoma, San Jose, and Sutter's Fort.

In Southern California, Mexican General José Castro and Governor Pío Pico abandoned Los Angeles. When Stockton's forces entered Los Angeles unresisted on August 13, 1846, the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete. Stockton, however, left too small a force (36 men) in Los Angeles, and the Californians, acting on their own and without help from Mexico, led by José María Flores, forced the small American garrison to retire in late September.

Two hundred reinforcements were sent by Stockton, led by US Navy Captain William Mervine, but were repulsed in the Battle of Dominguez Rancho, October 7–9, 1846, near San Pedro, where 14 U.S. Marines were killed. Meanwhile, General Kearny with a much-reduced squadron of 100 dragoons finally reached California after a grueling march from Santa Fe, New Mexico across the Sonoran Desert. On December 6, 1846, they fought the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego, where 18 of Kearny's troops were killed—the largest number of American casualties lost in any battle in California.

Stockton rescued Kearny's surrounded troops and, with their combined force, they moved northward from San Diego. Entering the present-day Orange County area on January 8, they linked up with Frémont's northern force. With the combined American forces totaling 660 troops, they fought the Californians in the Battle of Rio San Gabriel. The next day, January 9, 1847, they fought the Battle of La Mesa. Three days later, on January 12, 1847, the last significant body of Californians surrendered to American forces. That marked the end of the war in California. On January 13, 1847, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed.

On January 26, 1847, Army lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman and his unit arrived in Monterey. On March 15, 1847, Col. Jonathan D. Stevenson's Seventh Regiment of New York Volunteers of about 900 men began to arrive. All of these troops were still in California when gold was discovered in January 1848.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, marked the end of the Mexican–American War. In that treaty, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $18,250,000; Mexico formally ceded California (and other northern territories) to the United States; and the first international boundary was drawn between the U.S. and Mexico by treaty. The previous boundary had been negotiated in 1819 between Spain and the United States in the Adams–Onís Treaty, which established the present border between California and Oregon. San Diego Bay is one of the few natural harbors in California south of San Francisco, and to claim this strategic asset the southern border was slanted to include the entire bay in California.

California under the United States (beginning 1848)

Population

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 8,000 | — | |

| 1850 | 120,000 | 1,400.0% | |

| 1860 | 379,994 | 216.7% | |

| 1870 | 560,247 | 47.4% | |

| Sources: 1850–1870 U.S. Census[48] | |||

The non-Indian population of California in 1840 was about 8,000, as confirmed by the California 1850 U.S. Census, which asked everyone their place of birth. The Indian population is unknown but has been variously estimated at about 30,000 to 150,000 in 1840. The population in 1850, the first U.S. census, does not count the Indian population and omits San Francisco, the largest city, as well as the counties of Santa Clara and Contra Costa, all of whose tabulations were lost before they could be included in the totals. Some estimates can be obtained from the Alta Californian newspapers published in San Francisco in 1850. A corrected California 1850 Census would go from 92,597 (the uncorrected "official number") to over 120,000. The 1850 U.S. Census, the first census that included the names and sex of everyone in a family, showed only 7,019 females, with 4,165 non-Indian females older than 15 in the state.[49] To this should be added about 1,300 women older than 15 from San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Contra Costa counties whose censuses were lost and not included in the totals.[50] There were less than 10,000 females in a total California population (not including Indians who were not counted) of about 120,000 residents in 1850. About 3.0% of the Gold Rush "Argonauts" before 1850 were female or about 3,500 female Gold Rushers, compared to about 115,000 male California Gold Rushers.

By California's 1852 "special" State Census, the population had already increased to about 200,000, of which about 10% or 20,000 were female.[51] Competition by 1852 had decreased the steamship fare via Panama to about $200. Many of the new and successful California residents sent off for their wives, sweethearts and families to join them in California. After 1850 the Panama Railroad (completed 1855) was already working its way across the Isthmus of Panama, making it ever easier to get to and from California in about 40 days. Additional thousands came via the California Trail, but this took longer—about 120 to 160 days. The "normal" male to female ratio of about one to one would not arrive until the 1950 census. California for over a century was short on females.

Gold Rush

In January 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in the Sierra Nevada foothills about 40 miles east of Sacramento – beginning the California Gold Rush, which had the most extensive impact on population growth of the state of any era.[52][53]

The miners settled in towns along what is now California State Highway 49, and settlements sprang up along the Siskiyou Trail as gold was discovered elsewhere in California (notably in Siskiyou County). The nearest deep-water seaport was San Francisco Bay, and the rapidly growing town of San Francisco became the home for bankers who financed exploration for gold.

The Gold Rush brought the world to California. By 1855, some 300,000 "Forty-Niners" had arrived from every continent; many soon left, of course—some rich, most not so fortunate. A precipitous drop in the Native American population occurred in the decade after the discovery of gold.

Interim government: 1846–1850

From mid-1846 to December, 1849, California was run by the U.S. military; local government continued to be run by alcaldes (mayors) in most places, but now some were Americans. Bennett C. Riley, the last military governor, called a constitutional convention to meet in Monterey in September 1849. Its 48 delegates were mostly pre-1846 American settlers; eight were Californians. They unanimously outlawed slavery and set up a state government that operated for nearly 8 months before California was given official statehood by Congress on September 9, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850.[54]

After Monterey, the state capital was variously San Jose (1850–1851), Vallejo (1852–1853) and Benicia (1853–1854), until Sacramento was finally selected in 1854.

Early separatist movements

Californians (dissatisfied with inequitable taxes and land laws) and pro-slavery Southerners in lightly-populated rural areas of Southern California attempted three times in the 1850s to achieve a separate statehood or territorial status separate from Northern California. The last attempt, the Pico Act of 1859, was passed by the California State Legislature, signed by the state governor, approved overwhelmingly by voters in the proposed "Territory of Colorado" and sent to Washington, D.C., with a strong advocate in Senator Milton Latham. However, the secession crisis in 1860 led to the proposal never coming to a vote.[55][56]

Law and the legal profession

For the most part, the American frontier spread West slowly, with the first stage a long territorial apprenticeship under the control of a federal judge and federal officials. After few decades, the transition was made to statehood, usually by adapting constitutional and legal procedures from previous states of residence, and using the lawyers who practiced during the territorial. California was entirely different. Its hurried transition from Mexican possession to United States statehood by 1850, brought a very large new population from across the world, bringing many different legal traditions with them. Legal conditions were chaotic at first. The new state lacked judicial precedents, prisons, competent lawyers, and a coherent system of laws.[57] Alarmed citizens formed vigilante tribunals, most famously in the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance in the 1850s. Absent an established system of law and order, they dispensed raw justice quickly through drum-head trials, whipping, banishment, or hanging.[58] As a body of law developed, the courts set precedents on such issues as women's contractual rights, real estate and mortgages, tort law, and review of flawed statutes. an elaborate new body of law was quickly constructed to deal with gold mining claims and water rights.[59] There was vicious mistreatment of Indians and the Chinese, and to a lesser extent against Mexicans.[60] By the 1860s, San Francisco had developed a professional police force so it could dispense with the use of vigilante actions.[61] Statewide by 1865, the courts, legislators, and legal profession had established a legal system that operated smoothly.[62]

California Genocide (1846-1871)

The California genocide consisted of actions taken by the United States in the 19th century, following the American Conquest of California from Mexico, that resulted in the dramatic decrease of the indigenous population of California. Between 1849 and 1870 it is conservatively estimated that American colonists murdered some 9,500 California Natives, and acts of enslavement, kidnapping, rape, child separation and displacement were widespread, encouraged, carried out by and tolerated by state authorities and militias.

Mariposa War (1850-1851)

The gold rush increased pressure on the Native Americans of California, because miners forced Native Americans off their gold-rich lands. Many were pressed into service in the mines; others had their villages raided by the army and volunteer militia. Some Native American tribes fought back, beginning with the Ahwahnechees and the Chowchilla in the Sierra Nevada and San Joaquin Valley leading a raid on the Fresno River post of James D. Savage, in December 1850. In retaliation Mariposa County Sheriff James Burney led local militia in an indecisive clash with the natives on January 11, 1851 on a mountainside near present-day Oakhurst, California.

Mendocino War (1859-1860)

Following the Round Valley Settler Massacres from 1856-1859, the Mendocino War was the genocide of the Yuki (mainly Yuki tribes) between July 1859 to January 18, 1860 by white settlers in Mendocino County, California. It was caused by settler intrusion and slave raids on native lands and subsequent native retaliation, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of natives. In 1859, a band of locally sponsored rangers led by Walter S. Jarboe, called the Eel River Rangers, raided the countryside in an effort to remove natives from settler territory and move them onto the Nome Cult Farm, an area near the Mendocino Indian Reservation. The genocide killed at least 283 Indian men and countless women and children in 23 engagements over the course of six months. They were reimbursed by the U.S. government for their campaign.

The Civil War

Because of the distance factor, California played a minor role in the American Civil War. Although some settlers sympathized with the Confederacy, they were not allowed to organize, and their newspapers were closed down. Former Senator William M. Gwin, a Confederate sympathizer, was arrested and fled to Europe. Powerful capitalists dominated Californian politics through their control of mines, shipping, and finance. They controlled the state through the new Republican Party. Nearly all the men who volunteered as soldiers stayed in the West to guard facilities, suppress secessionists, or fight the Native Americans. Some 2,350 men in the California Column marched east across Arizona in 1862 to expel the Confederates from Arizona and New Mexico. The California Column then spent most of the remainder of the war fighting Native Americans in the area.[63]

Labor

In his maiden speech before the United States Senate, California Senator David C. Broderick stated, "There is no place in the Union, no place on earth, where labor is so honored and so well rewarded..." as in California. Early immigrants to California came with skills in many trades, and some had come from places where workers were being organized. California's labor movements began in San Francisco, the only large city in California for decades and once the center of trade-unionism west of the Rockies. Los Angeles remained an open-shop stronghold for half a century until unions from the north collaborated to make California a union state.

Because of San Francisco's relative isolation, skilled workers could make demands that their counterparts on the East Coast could not. Printers first attempted to organize in 1850, teamsters, draymen, lightermen, riggers and stevedores in 1851, bakers and bricklayers in 1852, caulkers, carpenters, plasterers, brickmasons, blacksmiths and shipwrights in 1853 and musicians in 1856. Although these efforts required several starts to become stabilized, they did earn better pay and working conditions and began the long efforts of state labor legislation. Between 1850 and 1870, legislation made provisions for payment of wages, the mechanic's lien and the eight-hour workday.

It was said that during the last half of the 19th century more of San Francisco's workers enjoyed an eight-hour workday than any other American city. The molders' and boilermakers' strike of 1864 was called in opposition to a newly formed iron-works employers association which threatened a one thousand dollar a day fine on any employer who granted the strikers' demands and had wired for strikebreakers across the country. The San Francisco Trades Union, the city's first central labor body, sent a delegation to meet a boatload of strikebreakers at Panama and educated them. They arrived in San Francisco as enrolled union members.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, California continued to grow rapidly. Independent miners were largely displaced by large corporate mining operations. Railroads began to be built, and both the railroad companies and the mining companies began to hire large numbers of laborers. The decisive event was the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869; six days by train brought a traveler from Chicago to San Francisco, compared to six months by ship. The era of comparative protection for California labor ended with the arrival of the railroad. For decades after, labor opposed Chinese immigrant workers and politicians pushed anti-Chinese legislation.

Importation of slaves or so-called "contract" labor was fought by miners and city workers and made illegal through legislation in 1852.

The first statewide federated labor body was the Mechanics' State Council that championed the eight-hour day against the employers' 1867 "Ten Hour League". The Council affiliated with the National Labor Union, America's first national union effort. By 1872 Chinese workers comprised half of all factory workers in San Francisco and were paid wages far below white workers. "The Chinese Must Go!" was the slogan of Denis Kearney, a prominent labor leader in San Francisco. He appeared on the scene in 1877 and led sandlot vigilantes that roamed the city beating Chinese and wrecking their businesses.

Twice the seamen of the West Coast had tried to organize a union, but were defeated. In 1875, the Seaman's Protective Association was established and began the struggle for higher wages and better conditions on ships. The effort was joined by Henry George, editor of the San Francisco Post. The legislative struggle to enforce laws against brutal ship's captains and the requirement that two-thirds of sailors be Americans was proposed, and the effort was carried for thirty years by Andrew Furuseth and the Sailors' Union of the Pacific after 1908, and the International Seamen's Union of America. The Coast's Seamen's Journal was founded in 1887, for years the most important labor journal in California.

Concurrently, waterfront organizing led to the Maritime Federation of the Pacific.

Labor politics and the rise of Nativism

Thousands of Chinese men arrived in California to work as laborers, recruited by industry as low-wage workers. Over time, conflicts in the gold fields and cities created resentment toward the Chinese laborers. During the decade-long depression after the transcontinental railroad was completed, white workers began to lay blame on the Chinese laborers. Many Chinese were expelled from the mine fields. Some returned to China after the Central Pacific was built. Those who stayed mostly moved to the Chinatowns in San Francisco and other cities, where they were relatively safe from violent attacks they suffered elsewhere.

From 1850 through 1900, anti-Chinese nativist sentiment resulted in the passage of innumerable laws, many of which remained in effect well into the middle of the 20th century. The most flagrant episode was probably the creation and ratification of a new state constitution in 1879. Thanks to vigorous lobbying by the anti-Chinese Workingmen's Party, led by Denis Kearney (an immigrant from Ireland), Article XIX, Section 4 forbade corporations from hiring Chinese "coolies", and empowered all California cities and counties to completely expel Chinese persons or to limit where they could reside. The law was repealed in 1952.

The 1879 constitutional convention also dispatched a message to Congress pleading for strong immigration restrictions, which led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The act was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1889, and it would not be repealed by Congress until 1943. Similar sentiments led to the development of the Gentlemen's Agreement with Japan, by which Japan voluntarily agreed to restrict emigration to the United States. California also passed an Alien Land Act which barred aliens, especially Asians, from holding title to land. Because it was difficult for people born in Asia to obtain U.S. citizenship until the 1960s, land ownership titles were held by their American-born children, who were full citizens. The law was overturned by the California Supreme Court as unconstitutional in 1952.

In 1886, when a Chinese laundry owner challenged the constitutionality of a San Francisco ordinance clearly designed to drive Chinese laundries out of business, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor, and in doing so, laid the theoretical foundation for modern equal protection constitutional law. See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886). Meanwhile, even with severe restrictions on Asian immigration, tensions between unskilled workers and wealthy landowners persisted up to and through the Great Depression. Novelist Jack London writes of the struggles of workers in the city of Oakland in his 1913 novel The Valley of the Moon.

Rise of the railroads

The Big Four were the famous railroad tycoons who built the Central Pacific Railroad, (C.P.R.R.), which formed the western portion of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States. They were Leland Stanford, (1824–1893), Collis Potter Huntington (1821–1900), Mark Hopkins (1813–1878), and Charles Crocker (1822–1888).[64] The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines permanently linked California to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed immeasurably to the state's unrivaled social, political, and economic development.[65][66]

The Big Four dominated California's economy and politics in the 1880s and 1890s, and Collis P. Huntington became one of the most hated men in California. One typical California textbook argues:

- Huntington came to symbolize the greed and corruption of late-nineteenth-century business. Business rivals and political reformers accused him of every conceivable evil. Journalists and cartoonists made their reputations by pillorying him.... Historians have cast Huntington as the state's most despicable villain."[67]

Huntington, however, defended himself:

- The motives back of my actions have been honest ones and results have redounded far more to the benefit of California that have to my own."[68]

Late developments

1898 saw the founding of the League of California Cities, an association intended to fight city government corruption, coordinate strategies for cities facing issues such as electrification, and to lobby the state government on behalf of cities.

See also

- History of California 1900–present

- History of California

- History of the west coast of North America

- List of Governors of California before admission

- Maritime history of California

- Politics of California before 1900

- Mexican California topics (1822–1848)

- Spanish California topics (1769–1822)

References

- "Big Era Two: Human Beings Almost Everywhere – 200,000 – 10,000 Years Ago" (PDF). World History For Us All. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2006. Retrieved September 17, 2020 – via San Diego State University.

- Starr, Kevin. California: A History, New York, Modern Library (2005), p. 13

- "Survey of California and Other Indian Languages". Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- "California Indian Cultures". Four Directions Institute. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Virtual Tours". Archived from the original on April 29, 2009.

- "Acorn consumption". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "Acorn preparation". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Lightfoot, Kent and Otis Parrish (2009). California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction. California Natural History Guide Series, No. 69. University of California Press, Berkeley. pp. 2–13. ISBN 978-0520256903

- Neil G. Sugihara; Jan W. Van Wagtendonk; Kevin E. Shaffer; Joann Fites-Kaufman; Andrea E. Thode, eds. (2006). "17". Fire in California's Ecosystems. University of California Press. pp. 417. ISBN 978-0-520-24605-8.

- Blackburn, Thomas C. and Kat Anderson, ed. (1993). Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press. ISBN 0879191260.

- Cunningham, Laura (2010). State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California. Berkeley, California: Heyday. pp. 135, 173–202. ISBN 978-1597141369.

- Anderson, M. Kat (2006). Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources. University of California Press. ISBN 0520248511.

- Gibson, Carrie (2019). "Chapter 3". El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0802127020.

- Starr, Kevin (2005). "Chapter 2". California: A History. New York: Random House - The Modern Library. ISBN 978-0679642404.

- Wood, Mark (March 11, 2014). "The Island of California". Pomona College Magazine. Pomona College. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- Elsasser, Albert B. (1979). "Explorations of Hernando Alarcón in the Lower Colorado River Region, 1540". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 1 (1).

- Price, Arthur L. (November 3, 1912). "How California Got Its Name" (Volume CXIL, No 156). San Francisco, California: The San Francisco Call. The San Francisco Sunday Call. p. Magazine Section, Part 1.

- Rolle 1987, pp. 34–35.

- U.S. National Park Service official website about Juan Cabrillo. (retrieved 2006-12-18)

- Carlson, Jon D. (2011). Myths, State Expansion, and the Birth of Globalization: A Comparative Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-137-01045-2. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- Hoover, Mildred Brooke; Kyle, Douglas E., eds. (1990). Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-8047-1734-2. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- Tillman, Linda C.; Scheurich, James Joseph (August 21, 2013). The Handbook of Research on Educational Leadership for Equity and Diversity. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-135-12843-2.

- Huping Ling (April 29, 2009). Asian America: Forming New Communities, Expanding Boundaries. Rutgers University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8135-4867-8.

- Von der Porten, Edward (January 1975). "Drake's First Landfall". Pacific Discovery, California Academy of Sciences. 28 (1): 28–30.

- Rolle 1987, pp. 40–41.

- Sugden, John (2006). Sir Francis Drake. London: Pimlico. pp. 136–37. ISBN 978-1-844-13762-6.

- Rolle 1987, p. 44.

- Information from Monterey County Museum about Vizcaino's voyage and Monterey landing (retrieved 2006-12-18); Summary of Vizcaino expedition diary (retrieved 2006-12-18)

- Mariano Ardash Bonialian, El Pacífico hispanoamericano: política y comercio asiático en el Imperio Espan~ol (1680–1784): la centralidad de lo marginal. México D.F.: El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Historicos, 2012.

- For English summary, see review of Bonialian's book by Marie Christine Duggan at https://eh.net/book_reviews/el-pacifico-hispanoamericano-politica-y-comercio-asiatico-en-el-imperio-espanol-1680-1784/

- "The French in Early California". Ancestry Magazine. Retrieved March 24, 2006.

- See Bonialian, op. cit, p. 277; or in English book review by Duggan, op. cit.

- Kino, E. F., & In Bolton, H. E. (1919). Kino's historical memoir of Pimería Alta: A contemporary account of the beginnings of California, Sonora, and Arizona. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company, pages 215–216.

- Hackel, Steven W., Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005)

- See for example, Randall Milliken, A Time of Little Choice: Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769–1810 (Menlo Park: Ballena Press, 1995).

- see Marie Christine Duggan, "With and Without and Empire: Financing for California Missions Before and After 1810" in Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 85, No. 1, pp. 23–71; http://phr.ucpress.edu/content/ucpphr/85/1/23.full.pdf

- Earle E. Williams, "Tales of Old San Joaquin City", San Joaquin Historian, San Joaquin County Historical Society, Vol. IX, No. 2, April – June 1973. p.13, note 8. "El Camino Viejo ran along the eastern edge of the Coast Range hills in the San Joaquin Valley northward to the mouth of Corral Hollow. From this point it ran generally east-west through the hills and then down into the Livermore Valley and on to Mission San Jose. From there it turned northward, terminating at what is now the Oakland area. ... see Earle E. Williarms, Old Spanish Trails of the San Joaquin Valley (Tracy, California), 1965."

- Frank Forrest Latta, "El Camino Viejo á Los Angeles" – The Oldest Road of the San Joaquin Valley; Bear State Books, Exeter, 2006

- Field, Maria Antonia (1914). "California under Spanish Rule". Chimes of Mission Bells. San Francisco: Philopolis Press.

- José Bandini, in a note to Governor Echeandía or to his son, Juan Bandini, a member of the Territorial Deputation (legislature), noted that Alta California was bounded "on the east, where the Government has not yet established the [exact] border line, by either the Colorado River or the great Sierra (Sierra Nevada)." A Description of California in 1828 by José Bandini (Berkeley, Friends of the Bancroft Library, 1951), 3. Reprinted in Mexican California (New York, Arno Press, 1976). ISBN 0-405-09538-4

- "Fort Ross, California". Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- Charles B. Churchill, "Thomas Jefferson Farnham: An Exponent of American Empire in Mexican California". The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 60, No. 4 (Nov., 1991), pp. 517–537

- "Two years before the mast, and twenty-four years after: a personal narrative / by Richard Henry Dana, Jr". May 13, 2008. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884–1890) History of California, v.4, The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, complete text online Archived 2012-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, p.260

- Exploration du territoire de l'Orégon, des Californies et de la mer Vermeille, exécutée pendant les années 1840, 1841 et 1842..., Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1844

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884–1890) History of California, v.4, The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, complete text online Archived 2012-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, p.263–273.

- "Captain John Charles Fremont and the Bear Flag Revolt". California State Military Museum.

- "Resident Population Data – 2010 Census". Archived from the original on January 1, 2011.

- U.S. Seventh Census 1850: California Accessed 18 Aug 2011

- Newspaper accounts in 1850 (Alta Californian) gives the population of San Francisco at 21,000; the special California state census of 1852 finds 6,158 residents of Santa Clara County and 2,786 residents of Contra Costa County. Adding an estimate of the women (using the same ratio of men to women found in other mining communities) gives about 1,300 more females that should have been included in the 1850 census.

- "Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789–1945"; accessed 14 Apr 2011

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Going to California: 49ers and the Gold Rush".

- Richard B. Rice et al., The Elusive Eden (1988) pp. 191–95

- Michael DiLeo, Eleanor Smith, Two Californias: The Truth about the Split-state Movement. Island Press, Covelo, California, 1983, pp. 9–30. Nearly 75% of voters in the proposed Territory of Colorado voted for separate status.

- California, Historical Society of Southern; California, Los Angeles County Pioneers of Southern (January 1, 1901). "The Quarterly" – via Google Books.

- Gordon Morris Bakken, "The courts, the legal profession, and the development of law in early California." California History 81.3/4 (2003): 74–95.

- Joseph M. Kelly, "Shifting Interpretation of the San-Francisco Vigilantes." Journal of the West 24.1 (1985): 39–46.

- Mark Kanazawa, . Golden rules: The origins of California water law in the gold rush (2015).

- Sucheng Chan, "A People of Exceptional Character: Ethnic Diversity, Nativism, and Racism in the California Gold Rush." California History 79.2 (2000): 44–85.

- Philip J. Ethington, "Vigilante and the police: The creation of a professional police bureaucracy in San Francisco, 1847–1900." Journal of Social History 21.2 (1987): 197-227. online

- Bakken, "The courts, the legal profession, and the development of law in early California." pp. 90–95.

- Leo P. Kibby, "With Colonel Carleton and the California Column." Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly 41.4 (1959): 337-344 online.

- Richard Rayner, The Associates: Four Capitalists Who Created California (2007)

- Richard J. Orsi, "Railroads in the History of California and the Far West: An Introduction." California History (1991): 2–11. in JSTOR

- Richard J. Orsi, Sunset limited: the Southern Pacific Railroad and the development of the American West, 1850–1930 (Univ of California Press, 2005).

- Richard B. Rice, William A. Bullough, and Richard J. Orsi, The elusive Eden: A new history of California (1988) p 247.

- Dennis Drabelle (2012). The Great American Railroad War: How Ambrose Bierce and Frank Norris Took On the Notorious Central Pacific Railroad. St. Martin's Press. p. 178. ISBN 9781250015051.

Sources

- Rolle, Andrew (1987). California: A History (4th ed.). Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson. ISBN 0-88295-839-9. OCLC 13333829.

Further reading

Surveys

- Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, Vol. 18–24, History of California to 1890; complete text online. Written in the 1880s, this is the most detailed history.

- Robert W. Cherny, Richard Griswold del Castillo, and Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo. Competing Visions: A History of California (2005), textbook

- Gutierrez, Ramon A. and Richard J. Orsi (ed.) Contested Eden: California before the Gold Rush (1998), essays by scholars

- Carolyn Merchant, ed. Green Versus Gold: Sources in California's Environmental History (1998), readings in primary and secondary sources

- Rawls, James; Walton Bean (2003). California: An Interpretive History. McGraw-Hill, New York. ISBN 0-07-052411-4., 8th edition of standard textbook

- Rice, Richard B., William A. Bullough, and Richard J. Orsi. Elusive Eden: A New History of California, 3rd ed. (2001), standard textbook

- Rolle, Andrew F. California: A History, 6th ed. (2003), standard textbook

- Starr, Kevin. California: A History (2005), interpretive history

- Sucheng, Chan, and Spencer C. Olin, eds. Major Problems in California History (1996), primary and secondary documents

To 1846

- Beebe, Rose Marie; Senkewicz, Robert M., eds. (2001). Lands of Promise and Despair; Chronicles of Early California, 1535–1846. Santa Clara, California: Santa Clara University., primary sources

- Beebe, Rose Marie (2006). Testimonios: Early California through the Eyes of Women, 1815–1848. Berkeley: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-1597140324.

- Camphouse, M. (1974). Guidebook to the Missions of California. Anderson, Ritchie & Simon, Los Angeles, California. ISBN 0-378-03792-7.

- Chartkoff, Joseph L.; Chartkoff, Kerry Kona (1984). The Archaeology of California. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Chapman, Charles E. A History of California: The Spanish Period. Macmillan, 1991

- Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Fagan, Brian (2003). Before California: An Archaeologist Looks at Our Earliest Inhabitants. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The Destruction of California Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Hurtado, Albert L. John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier (2006). University of Oklahoma Press, 416 pp. ISBN 0-8061-3772-X.

- Johnson, P., ed. (1964). The California Missions. Lane Book Company, Menlo Park, California.

- McLean, James (2000). California Sabers. Indiana University Press.

- Lightfoot, Kent. Indians, Missionaries, and Merchants: The Legacy of Colonial Encounters on the California Frontiers (2004)

- Moorhead, Max L. (1991). The Presidio: Bastion of the Spanish Borderlands. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma. ISBN 0-8061-2317-6.

- Moratto, Michael J.; Fredrickson, David A. (1984). California Archaeology. Orlando: Academic Press.