Setback (architecture)

A setback, sometimes called step-back, is a step-like recession in a wall.[1] Setbacks were initially used for structural reasons, but now are often mandated by land use codes, or are used for aesthetic reasons. In densely built-up areas, setbacks also help get more daylight and fresh air to the street level.[2][3][4] Importantly, a setback helps lower the building's center of mass, making it more stable.

.jpg.webp)

History

Setbacks were used by ancient builders to increase the height of masonry structures by distributing gravity loads produced by building materials such as clay, stone, or brick. This was achieved by regularly reducing the footprint of each level located successively farther from the ground. Setbacks also allowed the natural erosion to occur without compromising the structural integrity of the building. The most prominent example of a setback technique is the step pyramids of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, such as the Teppe Sialk ziggurat or the Pyramid of Djoser.

For centuries, setbacks were a structural necessity for virtually all multi-level load-bearing masonry buildings and structures.[5] As architects learned how to turn setbacks into an architectural feature, most setbacks were however less pronounced than in step pyramids and often skillfully masked by rich ornamentation.

The introduction of a steel frame structural system in the late 19th century eliminated the need for structural setbacks. The use of a frame building technology combined with conveniences such as elevators and motorized water pumps influenced the physical growth and density of buildings in large cities. Driven by the desire to maximize the usable floor area, some developers avoided the use of setbacks, creating in many instances a range of fire safety and health hazards. Thus, the 38-story[6] Equitable Building, constructed in New York in 1915, produced a huge shadow, said to "cast a noonday shadow four blocks long",[6] which effectively deprived neighboring properties of sunlight. It resulted in the 1916 Zoning Resolution, which gave New York City's skyscrapers their typical setbacks and soaring designs.

Setbacks and urban planning

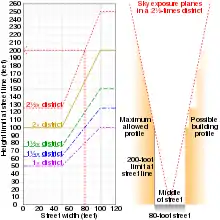

Today many jurisdictions rely on urban planning regulations, such as zoning ordinances, which use setbacks to make sure that streets and yards are provided more open space and adequate light and air. For example, in high density districts, such as Manhattan in New York, front walls of buildings at the street line may be limited to a specified height or number of stories. This height is also called base height which is only required if the building will exceed maximum base height.[7] Above that height, the buildings are required to set back behind a theoretical inclined plane, called sky exposure plane, which cannot be penetrated by the building's exterior wall. For the same reason, setbacks may also be used in lower density districts to limit the height of perimeter walls above which a building must have a pitched roof or be set back before rising to the permitted height.[8]

In many cities, building setbacks add value to the interior real estate adjacent to the setback by creating usable exterior spaces. These setback terraces are prized for the access they provide to fresh air, skyline views, and recreational uses such as gardening and outdoor dining. In addition, setbacks promote fire safety by spacing buildings and their protruding parts away from each other and allow for passage of firefighting apparatus between buildings.

In the United States, setback requirements vary among municipalities. For example, the absence of sky exposure plane provisions in Chicago's Zoning Code makes the Chicago skyline quite different from the skyline of New York where construction of tall buildings was guided by the zoning ordinance since 1916. The New York City Zoning Ordinance also provided another kind of setback guideline, one that was intended to increase the amount of public space in the city. This was achieved by increasing the minimum setback at street level, creating in each instance an open space, often referred to as plaza, in front of the building.

Increasing setbacks make the Empire State Building in New York taper with height.

Increasing setbacks make the Empire State Building in New York taper with height. The Malloch Building in San Francisco is stepped back along the contour of the steep side of Telegraph Hill.

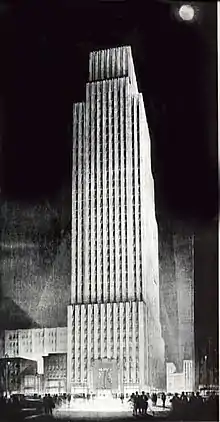

The Malloch Building in San Francisco is stepped back along the contour of the steep side of Telegraph Hill. New York's Daily News Building features a number of setbacks. It was designed by architect Raymond Hood in 1929. The 1916 Zoning Resolution of New York led to many soaring, setbacked towers.

New York's Daily News Building features a number of setbacks. It was designed by architect Raymond Hood in 1929. The 1916 Zoning Resolution of New York led to many soaring, setbacked towers.

See also

References

- Setback. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. p. 1725. ISBN 978-1-59339-492-9. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Mazzolani, Federico; Herrera, Ricardo (2012). Behaviour of Steel Structures in Seismic Areas: STESSA 2012. CRC Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-0-203-11941-9. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "Editorial Comment". American Architect and Architecture. J. R. Osgood & Company. 133: 83. 20 January 1928. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Jaffe, Martin S.; Erley, Duncan (1979). Protecting Solar Access for Residential Development: A Guidebook for Planning Officials. American Planning Association. p. 61. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Cornelius Steckner: Baurecht und Bauordnung. Architektur, Staatsmedizin und Umwelt bei Vitruv, in: Heiner Knell, Burkhardt Wesenberg (Hrsg.), Vitruv – Kolloquium 1982, Technische Hochschule Darmstadt 1984, S. 259–277.

- Allen, Irving Lewis (1995). "Skyscrapers". In Kenneth T. Jackson (ed.). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, CT & London & New York: Yale University Press & The New-York Historical Society. pp. 1074. ISBN 978-0-300-05536-8.

- "Zoning Glossary - DCP". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- Ward, David; Zunz, Olivier (1992). Landscape of Modernity: Essays on New York City, 1900-1940. Russell Sage Foundation. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-61044-550-4. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

Further reading

- Alexander, Christopher. A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press, 1977.

- Koolhaas, Rem. Delirious New York. Monacceli Press, reprint 1997.