Ship's wheel

A ship's wheel or boat's wheel is a device used aboard a water vessel to steer that vessel and control its course. Together with the rest of the steering mechanism, it forms part of the helm. It is connected to a mechanical, electric servo, or hydraulic system which alters the vertical angle of the vessel's rudder relative to its hull. In some modern ships the wheel is replaced with a simple toggle that remotely controls an electro-mechanical or electro-hydraulic drive for the rudder, with a rudder position indicator presenting feedback to the helmsman.

History

Prior to the invention of the ship's wheel, the helmsman relied on a tiller—a horizontal bar fitted directly to the top of the rudder post—or a whipstaff—a vertical stick acting on the arm of the ship's tiller. Near the start of the 18th century, a large number of vessels appeared using the ship's wheel design, but historians are unclear when the approach was first used.[1] Some modern ships have replaced the wheel with a simple toggle that remotely controls an electromechanical or electrohydraulic drive for the rudder, with a rudder position indicator presenting feedback to the helmsman.

Design

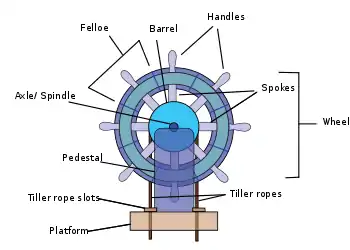

A typical ship's wheel is composed of eight cylindrical wooden spokes (though sometimes as few as six or as many as ten) shaped like balusters and all joined at a central wooden hub or nave (sometimes covered with a brass nave plate) which housed the axle. The square hole at the centre of the hub through which the axle ran is called the drive square and was often lined with a brass plate (and therefore called a brass boss, though this term was used more often to refer to a brass hub and nave plate) which was frequently etched with the name of the wheel's manufacturer. The outer rim is composed of sections each made up of stacks of three felloes, the facing felloe, the middle felloe, and the after felloe. Because each group of three felloes at one time made up a quarter of the distance around the rim, the entire outer wooden wheel was sometimes called the quadrant. Each spoke ran through the middle felloe creating a series of handles beyond the wheel's rim. One of these handles/ spokes was frequently provided with extra grooves at its tip which could be felt by a helmsman steering in the dark and used by him to determine the exact position of the rudder—this was the king spoke and when it pointed straight upward the rudder was believed to be dead straight to the hull. The completed ship's wheel and associated axle and pedestal(s) might even be taller than the person using it. The wood used in construction of this type of wheel was most often either teak or mahogany, both of which are very durable tropical hardwoods capable of surviving the effects of salt water spray and regular use without significant decomposition. Modern design—particularly on smaller vessels—can deviate from the template.

Mechanism

.gif)

The steering gear of earlier ships' wheels sometimes consisted of a double wheel where each wheel was connected to the other with a wooden spindle that ran through a barrel or drum. The spindle was held up by two pedestals that rested on a wooden platform, often no more than a grate. A tiller rope or tiller chain (sometimes called a steering rope or steering chain) ran around the barrel in five or six loops and then down through two tiller rope/ chain slots at the top of the platform before connecting to two sheaves just below deck (one on either side of the ship's wheel) and thence out to a pair of pulleys before coming back together at the tiller and connecting to the ship's rudder. Movement of the wheels (which were connected and moved in unison) caused the tiller rope to wind in one of two directions and angled the tiller left or right. In a typical and intuitive arrangement, a forward-facing helmsman turning the wheel counterclockwise would cause the tiller to angle to starboard and therefore the rudder to swing to port causing the vessel to also turn to port (see animation).[2]:p.152 On many vessels the helmsman stood facing the rear of the ship with the ship's wheel before him and the rest of the ship behind him— this still meant that the direction of travel of the wheel at its apex corresponded to the direction of turn of the ship. Having two wheels connected by an axle allowed two people to take the helm in severe weather when one person alone might not have had enough strength to control the ship's movements.

Gallery

Britannia Yacht Club's Commodore Boardroom features a ship's wheel table

Britannia Yacht Club's Commodore Boardroom features a ship's wheel table USS LST-325 ship's wheel and engine order telegraph

USS LST-325 ship's wheel and engine order telegraph U.S. Navy personnel aboard USS Constitution, by the ship's wheel

U.S. Navy personnel aboard USS Constitution, by the ship's wheel

See also

References

- "Ship Steering Wheel History". Articlesfactory.com. 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- zu Mondfeld, Wolfram (2007) [1977]. Historic Ship Models. New York City: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4027-2186-1. OCLC 60525064. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steering wheels (ship part). |