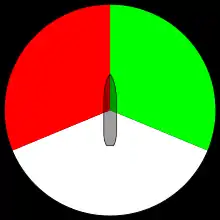

Port and starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms of orientation that deal unambiguously with the structure of vessels, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, seen by an observer aboard the vessel looking forward.

.jpg.webp)

Vessel structures are largely bilaterally symmetrical, meaning they have mirror-image left and right halves if divided sagittally. One asymmetric feature is that on ships where access is at the side, this access is usually only provided on the port side.

Side

Port and starboard unambiguously refer to the left and right side of the vessel, not the observer. That is, the port side of the vessel always refers to the same portion of the vessel's structure, and does not depend on which way the observer is facing.

The port side is the side of the vessel which is to the left of an observer aboard the vessel and facing the bow, that is, facing forward towards the direction the vehicle is heading when underway, and the starboard is to the right of such an observer.[1]

This convention allows orders and information to be given unambiguously, without needing to know which way any particular crew member is facing.[2][3]

Etymology

.png.webp)

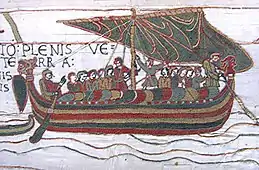

The term starboard derives from the Old English steorbord, meaning the side on which the ship is steered. Before ships had rudders on their centrelines, they were steered with a steering oar at the stern of the ship on the right hand side of the ship, because more people are right-handed.[2] The "steer-board" etymology is shared by the German Steuerbord and Dutch stuurboord, which gave rise to the French tribord, Spanish estribor and Portuguese estibordo.

Since the steering oar was on the right side of the boat, it would tie up at the wharf on the other side. Hence the left side was called port.[5] The Oxford English Dictionary cites port in this usage since 1543.[6]

Formerly, larboard was often used instead of port. This is from Middle English ladebord and the term lade is related to the modern load.[3] Larboard sounds similar to starboard and in 1844 the Royal Navy ordered that port be used instead.[7][8] The United States Navy followed suit in 1846. Larboard continued to be used well into the 1850s by whalers.[10] In chapter 12 of Life on the Mississippi (1883) Mark Twain writes larboard was used to refer to the left side of the ship (Mississippi River steamboat) in his days on the river -- circa 1857-1861.

An Anglo-Saxon record of a voyage by Ohthere of Hålogaland used the word "bæcbord" ("back-board") for the left side of a ship. With the steering rudder on the starboard side the man on the rudder had his back to the bagbord (Nordic for portside) side of the ship. The words for "port side" in other European languages, such as German Backbord, Dutch and Afrikaans bakboord, Spanish babor, Portuguese bombordo and French bâbord, are derived from the same root.

Importance of standard terms

The navigational treaty convention, the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea—for instance, as appears in the UK's Merchant Shipping (Distress Signals and Prevention of Collisions) Regulations 1996 (and comparable US documents from the US Coast Guard)[11]—sets forth requirements for maritime vessels to avoid collisions, whether by sail or powered, and whether a vessel is overtaking, approaching head-on, or crossing.[11]:11–12 To set forth these navigational rules, the terms starboard and port are essential, and to aid in in situ decision-making, the two sides of each vessel are marked, dusk to dawn, by navigation lights, the vessel's starboard side by green and its port side by red.[11]:15 Aircraft are lit in the same way.

See also

- Anatomical terms of location, another example of terms of directionality that do not depend on the location of the observer for things that are bilaterally symmetrical

- Dexter and sinister

- Direction (disambiguation)

- Glossary of nautical terms

- Handedness

- Laterality

- Proper right and proper left

- Reflection symmetry

- Sinistral and dextral

References

| Look up bæcbord, larboard, starboard, or port in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Why do ships use 'port' and 'starboard' instead of 'left' and 'right?'". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- NOS Staff (December 8, 2014). "Why Do Ships use "Port" and "Starboard" Instead of "Left" and "Right?"". NOAA National Ocean Service (NOS) Ocean Facts. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved February 2, 2017 – via OceanService.NOAA.gov.

- RMG Staff (February 2, 2017). "Port and Starboard: Why do Sailors say 'Port' and 'Starboard', for "Left" and "Right?"". Discover: Explore by Theme. Greenwich, England, UK: Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved February 2, 2017 – via RMG.co.uk.

- Grape, Wolfgang (1994). The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph. Art and Design Series. Munich, DEU: Prestel. p. 95. ISBN 978-3791313658. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Administration, US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric. "Unlike left and right, port and starboard refer to fixed locations on a vessel". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "port". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Admiralty Circular No. 2, November 22, 1844, cited in Western Courier newspaper (Plymouth) December 11, 1844.

- Norie, John William; Hobbs, J. S. (1847) [1840]. Sailing directions for the Bay of Biscay, including the coasts of France and Spain, from Ushant to Cape Finisterre (A new ed., rev. and considerably improved ed.). C. Wilson. p. 1. OCLC 41208722. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

An order, recently issued by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, states, that in order to prevent mistakes, which frequently occur from the similarity of the words starboard and larboard, in future, the word port is to be substituted for larboard, in all Her Majesty's ships or vessels.

- Morton, Harry (January 1, 1983). The Whale's Wake. University of Hawaii Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780824808303. Retrieved March 20, 2020 – via Google Books.

- MCA Staff (2004) [1996]. The Merchant Shipping (Distress Signals and Prevention of Collisions) Regulations 1996 (PDF). Southampton, ENG: Crown Department of Transport, Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). Retrieved February 2, 2017.