Shipwrecks of the inland Columbia River

Steamboats on the Columbia River system were wrecked for many reasons, including striking rocks or logs ("snags"), fire, boiler explosion, or puncture or crushing by ice. Sometimes boats could be salvaged, and sometimes not.

Collision

Collision could occur between steamboats, and probably did on many occasions near landings without serious loss. One instance of collision between boats causing the loss of one was in 1905, when Boneta was struck by Idaho near St. Joe, Idaho, and sank as a result. Gwendoline and Ruth were both sunk in narrow Jennings Canyon in 1897 when Ruth spun out of control after a log became jammed in her sternwheel, she struck the trailing boat Gwendoline and both went down. Oregona hit an anchored barge on the Willamette on December 26, 1913 and sank.[1]

Collision between steamboats and seagoing vessels did occur in the lower Columbia river. Such collisions would have been much more serious because of the generally much larger size and tough construction of the ocean-going vessel. Thus, on December 30, 1907, Annie Comings was rammed by the barque Europe in the Willamette River near St. Johns, and sank in three minutes, fortunately with no loss of life. Clatsop Chief was sunk in a similar collision with the steamship Oregon on February 28, 1881, that time four people drowned. F.B. Jones was rammed and sunk in 1907 on the lower Columbia by the tanker Asuncion.[1]

Snags, Rocks, Pilings and Piers

Collision with fixed or floating objects also happened, often with bad results. The crack boat Daisy Ainsworth hit a rock and sank just above the Upper Cascades on November 22, 1876. (In bad weather, her captain had made a minor navigation mistake).[2] Harvest Queen, despite her status a larger boat (846 tons, 200' long), was not immune. She struck a fishtrap piling on November 19, 1896, sank, and was later raised. Oregon hit a snag on the Willamette in 1854, was bumped loose by Gazelle (herself later to explode at Canemah not much later), then drifted downstream, hit a rock and sunk for good.[1]

Shoshone, which, with Norma, was one of the only two steamboats brought down the rapids of Hells Canyon,[3] struck a rock and sank at Salem in 1874.[1] Spokane hit a snag on the Coeur d'Alene River on April 5, 1887, sank and drowned a number of prominent people. She was salvaged but renamed Irene. Orient hit a rock in the Cowlitz in 1894, and then somehow burned during the attempted salvage.

The sternwheeler Dalles City sank on February 8, 1906, after striking a rock in the upper Columbia. Her crew said the steering gear had malfunctioned.[4] Madeline hit a snag on the Cowlitz and sank on March 23, 1925. Diamond O. struck a bridge at Vancouver, rolled over and sank on April 25, 1934.[1]

Boiler Explosion

These did not happen often, but they were very dangerous when they did, and generally resulted in severe casualties among the crew and passengers and the complete loss of the boat. Steamboat boiler explosions had been a common problem on the Mississippi River system well before the steamboats began serious operations in the Pacific Northwest in the 1850s. By 1852, the problem had gotten so bad that Congress enacted a law setting out detailed standards for inspection of steamboats and licensing of officers.[5] Considerable work was done in the 1840s and 1850s to understand what caused boiler explosions, and these came down to many causes, including general wear and tear, inadequate or poorly designed equipment, overworked boilers that were too small for the engines, general lack of engineering skill among boiler operators, and excessive demands for performance from the vessel's captain or management.[5] People noticed early on that most of boiler explosions occurred just as steamboats were leaving (or sometimes arriving at) a landing. This was true in two-thirds of the boiler explosions up to 1852. Steam pressure was supposed to be reduced during a landing, but this would make it more difficult to get off to a fast start, so too often pressure was kept up even though the engines weren't running to relieve the pressure by use of the steam generated by the boiler.[5] Under these circumstances, boiler explosions were much more likely.

The explosion came, we read again and again in the accounts of these accidents, while "the boat was backing out from the landing," or as "the boat was straightening out after leaving the wharf," or when "the signal to go ahead had just been given," or when "the engine had made but two or three revolutions." ... Careful steam practice required that the during a landing the fires be well checked, the supply pump be kept working, and steam be released through safety or blow-off valve in order to prevent undue accumulation of pressure. Circumstances, however, worked against sound practice, and very often in the flush decades of steamboating these precautions were not observed. To overcome the inertia of the vessel and get it safely away from the shore, perhaps against opposing winds and currents, a good head of steam was needed, and it was better to have too much than not enough.[6]

Early steamboat experience in the Oregon Country was unfortunately consistent with the Mississippi river boiler explosion pattern. Canemah was the first steamboat in Oregon to suffer a boiler explosion, on August 8, 1853, at or shortly below Champoeg landing on the Willamette River. One passenger was killed, but the boat survived.[7] Shoalwater's boiler exploded in May, 1853, at Rock Island, also on the Willamette River. No one was killed however and enough remained of the boat to allow it to be rebuilt as Fenix.[1] Details of these early explosions are lacking, but it is significant that at least one of them, Canemah, occurred at a landing.

Gazelle exploded at Canemah on April 8, 1854 while moored next to Wallamet and many people were killed.[1] (see Lone Fir Cemetery.) This was right by Oregon City, the most populous town in the Oregon Territory at the time. The details as described by Mills fit the pattern of landing explosions closely.

[S]he was at the portage road above the Falls, loading for her first regular trip upriver to Corvallis. At six in the morning her passengers came up the portage path, scrambled down the bank to the landing stage, and got aboard. Then the Gazelle proudly moved up to Canemah where she pulled in next to the Wallamet to load more freight. Smoke spiraled high from her stack while the work went on. Suddenly her engineer rushed onto the deck, scrambled ashore, and headed toward town. About a minute later the Gazelle's boiler blew up and she scattered herself all over the neighborhood.[8]

A coroner's jury fixed the blame on the negligence of the engineer, which was probably easy since he hadn't remained around to defend himself.[9] This may not have been entirely fair, as failure to maintain good steam could have readily lead to the loss of the boat by being swept over the nearby Willamette Falls, which was precisely the circumstance that happened a few years later, when a boat for lack of power was caught by the current and washed over the falls, killing the two men who hadn't been able to jump free and catch a rescuer's line.

Three years later, the little (60 gross tons)[9]Elk exploded without loss of life not far away on the Willamette near where the Yamhill flows into it.[1] As with Canemah, this was another where the steamer was under way at the time of the explosion, and yet surprisingly no loss of life occurred, although Elk's captain was blown out of the pilot house and into a cottonwood tree on the riverbank.[9]

No other boiler explosions occurred until Senator blew up at the dock at Alder Street in Portland on May 6, 1875. The explosion severed the mooring lines and the wreck drifted downriver and washed up at Albina.[1] Although by 1875 the steamboat act of 1852 had been in effect for over 20 years, the Senator's explosion just after taking on passengers fit well with the old pattern of loading on extra steam to make a quick start.

[S]he pulled out of her landing at Alder Street in Portland, dropped down to Oregon Steamship Company dock, and loaded some freight and passengers for upriver. Then she turned back to Alder Street, ready to take aboard a crowd for Oregon City. Lying at the dock was another steamboat, the Vancouver. The Senator arrived abreast the landing and shut off her engines preparatory to coming alongside her wheel idling, when her boiler gave way.[10]

The Senator explosion, as with the Gazelle 21 years before, was blamed on her engineer's having allowed low water in her boilers, so that when her engines were shut off, steam pressure built up too quickly, causing boiler failure.[9] Low water in the boiler was a situation where flames and hot gases from the firebox were allowed to have direct contact with the metal boiler tubes and other critical components when there should have been a barrier of water preventing this. The result would be either weakening of the metal over time or too quick a buildup in steam pressure, either one causing failure of the boiler jacket, that is, an explosion.[5] Hunter, in his thorough survey on the subject, cautions however that low boiler water, while often a cause of an explosion, was not always a good enough explanation, and that it had been shown by experiments as early as 1836 that a well-filled boiler could still explode, and that overheating caused by low water in the boiler frequently but not always led to an explosion.[5]

Low boiler water did however have the advantage of shifting the blame off from the captain for demanding immediate speed following the landing, or the owners, for pushing the schedule so hard that the engineer felt compelled to keep steam up while the engines were off line. Hunter makes the point that in 1838, when the spectacular explosion of the Moselle on the Ohio River near Cincinnati, caused a congressional investigation, that there was no existing body of knowledge or professional tradition for steamboat engineers.[5] By the time of the Senator explosion in 1875 and certainly by that of Annie Faxon in 1893, that would no longer have been true, and professional standards and skills would have been well established.

Even so, boiler explosions continued to occur. On January 18, 1912 Sarah Dixon exploded at Kalama, killing her captain, first mate, and fireman.[11] In 1943, Cascades exploded and burned in Portland.[1]

Fire

Fire was a great hazard. There were many instances of this. Mills states that fires were as rare as explosions[12] but this does not seem to be the case. Marshall collected at least thirteen separate instances of boats being destroyed by fire, and in some of these more than one boat was burned.[1]

Causes of Fire

Hunter well summarized the causes of fire in wooden steamboats:

Thin floors and partitions, light framing and siding, soft and resinous woods, the whole dried out by sun and wind and impregnated with oil and turpentine from paint, made the superstructure of the steamboat little more than an orderly pile of kindling wood.[13]

Hunter then points out that on the Mississippi-Ohio-Missouri boats he studied, the cargo itself was often highly flammable, consisting perhaps of loosely bound cotton bales, hale, sometimes in bales, sometimes not, straw, kegs of spirits and even gunpowder. Some of these conditions no doubt prevailed on many or most of the wooden steamboats in the Northwest. Until the coming of electrical generators, all the interiors of all the boats were lit by lanterns or open candle flames. Right in the middle of this potential bonfire had been planted one of the most powerful furnaces that the technology of the day could devise, which showered sparks and flaming materials out of the stacks, and which fed on an air supply funnelled by the boat's speed and the draft generated by the high stacks.[5]

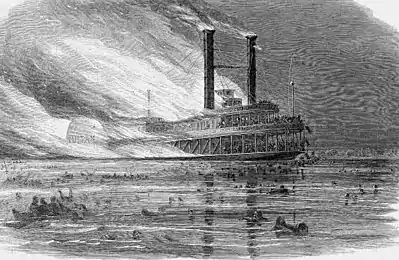

Rapidity of destruction

Fire could easily and rapidly spread throughout the whole boat in these circumstances. The draft created by the motion of the boat would quickly spread the fire along its whole length. If the fire could not be immediately quenched, the only option was to turn in to the shore as quickly as possible and try to evacuate the passengers.[5] Some examples of how rapidly the fire could destroy a vessel include the Telephone, near Astoria, and, far up river, Columbia, just north of the Canada–US border.

Fire on Telephone

The crack Telephone, one of the fastest on the lower Columbia, in November 1887, burned near Astoria, with 140 passengers and 32 crew on board, under the command of Captain U.B. Scott. Professor Mills describes the scene:

As soon as [Captain Scott] heard the alarm, he remembered fires on the Ohio steamers, and swung his wheel hard over to head for the shore. The engineer also heard the alarm and, feeling the long, trim boat heel for the turn, opened his throttle wide. Normally that would sweep the fire the length of the steamer, but he took the chance, and the Telephone cut for the bank st twenty miles an hour, crunching onto a shore of rolling pebbles that absorbed the shock. Quickly the passengers scrambled over the guards to dry land while the flames roared through the cabins.[14][15]

Captain Scott remained in the pilot house until its steps had burned, then dove out the window just before the boat's upper works collapsed. By then, the Astoria fire department had arrived on the scene, preserved enough of Telephone to allow her to be rebuilt and placed back into service.[2][9]

Fire on Columbia

The Columbia, a common steamboat name, was a sternwheeler build at 1893 at Little Dalles, and operating up the Arrow Lakes route of the Columbia River. The fire of Columbia was less spectacular than of Telephone, but the destruction was just as swift and more complete. On August 2, 1894, while lying at a woodlot just north of the Canada–US border, a crewman went to sleep without extinguishing his pipe. Fire broke out, and the entire vessel burned and was completely destroyed in the span of about ten minutes. According to the Kootenay County Mail:

The fire was discovered about 1:30 a.m., and in ten minutes the vessel was a total wreck. * * * The fire spread so rapidly that those on board had barely time to escape with such clothing as could be grabbed in their haste.[16]

Unlike Telephone which was beached and which had the ready aid of a shoreside fire department, Columbia sank in eight feet of water and was a total loss.

Other vessels lost to fire

Ranger burned on November 4, 1869 off Sauvie Island while en route Portland to Rainier.A.A. McCully burned on May 22, 1886 for an insurance loss of $12,000.[1] The large and almost new Nakusp burned at Arrowhead (near the north end of Upper Arrow Lake, in British Columbia) on December 23, 1897.[17]

J.N. Teal burned at Portland on October 22, 1907. Helen Hale burned in 1913 somewhere on the Upper Reach. Idaho, which had sunk Boneta in 1905, herself burned at Blackrock Bay in Lake Coeur d'Alene in 1915. Other boats destroyed by fire were R.C. Young, at Dove's Landing July 22, 1892 and Regulator, burned on ways at St. Johns,[4] January 24, 1906. Fire was so common a cause of destruction that in some cases little information is available as to the cause, date, or place, such as Messenger in 1879, Mascot in 1911, and Saint Paul, burned somewhere on the Columbia in 1915. Not every fire which destroyed a steamboat was ignited on the boat itself. Thus James Clinton was destroyed at Oregon City on April 23, 1861, after being ignited by sparks from burning buildings across the river.[1]

Multiple vessels lost at once to fire

There were several instances of more than one steamboat being destroyed by fire at once, always while moored together. There was a spectacular fire in Wenatchee on July 8, 1915. At that time, most of the boats of the Columbia & Okanogan Steamboat Company were moored together at a barge on the riverbank. Chelan was closest inshore, with North Star on the outside. In between were Columbia and Okanogan. Sometime after 11:00 p.m, a fire broke out on North Star, and quickly spread to other boats moored together with her, and all were destroyed.[1][2] Arson was suspected but never proved. The insurance on the boats had lapsed, so this fire, plus the sinking soon afterwards of the Enterprise, meant the end of Columbia and Okanogan Steamboat Co.[2]

Pairs of steamboats were destroyed on at least two occasions. On July 22, 1922, Lewiston and Spokane were moored together at Lewiston and fire destroyed both of them. Another North Star burned at St. Joe, Idaho in 1929, taking with her Boneta moored alongside.[1]

Rapids and Falls

Portland was swept over Willamette Falls on March 17, 1857 and destroyed, killing her captain and two others. E.N. Cooke was lost in the Clackamas Rapids, just north of Oregon City. Alexander Griggs was wrecked in 1905 at the Entiat Rapids. Selkirk was wrecked at Rock Island Rapids on May 15, 1906. Hercules was wrecked in 1933 at Three Mile Rapids.[1]

Floods

Powerful floods could overwhelm a steamboat and carry out of control it into the bank of a river, a rock or other obstruction, which was exactly what happened to the Georgie Burton in 1948 at the lower end of the Celilo Canal.[18]

Ice

The Corps of Engineers sternwheeler Asotin was crushed in the ice at Arlington in 1915.

High wind

Bonita was driven on a rock in the Columbia Gorge by a gale on December 7, 1892. Also in the Gorge, Dalles City was driven ashore by a sandstorm at Stevenson on September 14, 1912. A "hurricane" is described as having destroyed J.D. Farrell in Jennings Canyon in June 1898. Oakland was overcome by high winds on Upper Klamath Lake on October 6, 1912. Cowlitz was swamped by high winds and waves proceeding downriver from The Dalles in September 1931.[1]

Notes

- Marshall, Don, Oregon Shipwrecks, at 191-210, Binford and Mort, Portland, OR 1984 ISBN 0-8323-0430-1

- Timmen, Fritz, Blow for the Landing, 75-78, 134, Caxton Printers, Caldwell, ID 1972 ISBN 0-87004-221-1

- Mills, at 133-35

- "Dalles City Sinks". (February 9, 1906). The Morning Oregonian, p. 14.

- Hunter, Louis C., Steamboats on the Western Rivers, at 282-304, Dover Publications, Mineola, NY 1949 ISBN 0-486-27863-8

- Hunter, at 295-296

- Marshall, at 204, states the explosion was at the Champoeg Landing. Corning, at 63 states it was below the landing.

- Mills, at 115-16

- Mills, Randall V., Sternwheelers up Columbia, at 115-19, 193, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 1947 ISBN 0-8032-5874-7

- Mills, at 118

- Marshall, at 209. She was rebuilt, only to be destroyed by fire in 1926.

- Mills at 119

- Hunter, at 278

- Mills, at 119

- Timmen, at 134, describes the same scene, but states that Captain Scott gave the signal for full speed

- Turner, Sternwheelers, at 28-29

- Turner, Sternwheelers and Steam Tugs, at 258, Sono Nis Press, Victoria, BC 1984 ISBN 0-919203-15-9

- Marshall, at 206