Sholem Aleichem

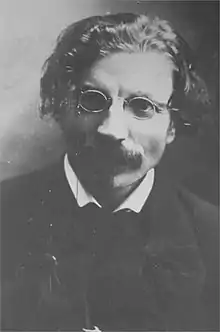

Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich, better known under his pen name Sholem Aleichem (Yiddish and Hebrew: שלום עליכם, also spelled שאָלעמ־אלייכעמ in Soviet Yiddish, [ˈʃɔləm aˈlɛjxəm]; Russian and Ukrainian: Шо́лом-Але́йхем) (March 2 [O.S. February 18] 1859 – May 13, 1916), was a leading Yiddish author and playwright.[1] The 1964 musical Fiddler on the Roof, based on his stories about Tevye the Dairyman, was the first commercially successful English-language stage production about Jewish life in Eastern Europe. The Hebrew phrase שלום עליכם (shalom aleichem) literally means "[May] peace [be] upon you!", and is a greeting in traditional Hebrew and Yiddish.[2]

Sholem Aleichem | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich March 2 [O.S. February 18] 1859 Pereiaslav, Russian Empire |

| Died | May 13, 1916 (aged 57) New York City, U.S. |

| Pen name | Sholem Aleichem (Yiddish: שלום עליכם) |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Genre | Novels, short stories, plays |

| Literary movement | Yiddish revival |

Biography

Solomon Naumovich (Sholom Nohumovich) Rabinovich (Russian: Соломо́н Нау́мович (Шо́лом Но́хумович) Рабино́вич) was born in 1859 in Pereiaslav and grew up in the nearby shtetl (small town with a large Jewish population) of Voronkiv, in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire (now in the Kyiv Oblast of central Ukraine).[3] His father, Menachem-Nukhem Rabinovich, was a rich merchant at that time.[4] However, a failed business affair plunged the family into poverty and Solomon Rabinovich grew up in reduced circumstances.[4] When he was 13 years old, the family moved back to Pereyaslav, where his mother, Chaye-Esther, died in a cholera epidemic.[5]

Sholem Aleichem's first venture into writing was an alphabetic glossary of the epithets used by his stepmother. At the age of fifteen, inspired by Robinson Crusoe, he composed a Jewish version of the novel. He adopted the pseudonym Sholem Aleichem, a Yiddish variant of the Hebrew expression shalom aleichem, meaning "peace be with you" and typically used as a greeting. In 1876, after graduating from school in Pereyaslav, he spent three years tutoring a wealthy landowner's daughter, Olga (Hodel) Loev (1865 – 1942).[6] From 1880 to 1883 he served as crown rabbi in Lubny.[7] On May 12, 1883, he and Olga married, against the wishes of her father. A few years later, they inherited the estate of Olga's father. In 1890, Sholem Aleichem lost their entire fortune in a stock speculation and fled from his creditors. Solomon and Olga had their first child, a daughter named Ernestina (Tissa), in 1884.[8] Daughter Lyalya (Lili) was born in 1887. As Lyalya Kaufman, she became a Hebrew writer. (Lyalya's daughter Bel Kaufman, also a writer, was the author of Up the Down Staircase, which was also made into a successful film.) A third daughter, Emma, was born in 1888. In 1889, Olga gave birth to a son. They named him Elimelech, after Olga's father, but at home they called him Misha. Daughter Marusi (who would one day publish "My Father, Sholom Aleichem" under her married name Marie Waife-Goldberg) was born in 1892. A final child, a son named Nochum (Numa) after Solomon's father was born in 1901 (under the name Norman Raeben he became a painter and an influential art teacher).

After witnessing the pogroms that swept through southern Russia in 1905, including Kyiv, Sholem Aleichem left Kyiv and immigrated to New York City, where he arrived in 1906. His family set up house in Geneva, Switzerland, but when he saw he could not afford to maintain two households, he joined them in Geneva in 1908. Despite his great popularity, he was forced to take up an exhausting schedule of lecturing to make ends meet. In July 1908, during a reading tour in Russia, Sholem Aleichem collapsed on a train going through Baranowicze. He was diagnosed with a relapse of acute hemorrhagic tuberculosis and spent two months convalescing in the town's hospital. He later described the incident as "meeting his majesty, the Angel of Death, face to face", and claimed it as the catalyst for writing his autobiography, Funem yarid [From the Fair].[3] He thus missed the first Conference for the Yiddish Language, held in 1908 in Czernovitz; his colleague and fellow Yiddish activist Nathan Birnbaum went in his place.[9]

Sholem Aleichem spent the next four years living as a semi-invalid. During this period the family was largely supported by donations from friends and admirers (among his friends and acquaintances were fellow Yiddish authors I. L. Peretz, Jacob Dinezon, Mordecai Spector, and Noach Pryłucki). In 1909, in celebration of his 25th Jubilee as a writer, his friend and colleague Jacob Dinezon spearheaded a committee with Dr. Gershon Levine, Abraham Podlishevsky, and Noach Pryłucki to buy back the publishing rights to Sholem Aleichem’s works from various publishers for his sole use in order to provide him with a steady income.[10] At a time when Sholem Aleichem was ill and struggling financially, this proved to be an invaluable gift, and Sholem Aleichem expressed his gratitude in a thank you letter in which he wrote,

“If I tried to tell you a hundredth part of the way I feel about you, I know that that would be sheer profanation. If I am fated to live a few years longer than I have been expecting, I shall doubtless be able to say that it’s your fault, yours and that of all the other friends who have done so much to carry out your idea of ‘the redemption of the imprisoned.’”[11]

— Sholem Aleichem

Sholem Aleichem moved to New York City again with his family in 1914. The family lived in the Lower East Side, Manhattan. His son, Misha, ill with tuberculosis, was not permitted entry under United States immigration laws and remained in Switzerland with his sister Emma.

Sholem Aleichem died in New York in 1916. He is buried in the main (old) section of Mount Carmel Cemetery in Queens, New York City.[12]

Literary career

Like his contemporaries Mendele Mocher Sforim, I.L. Peretz, and Jacob Dinezon, Sholem Rabinovitch started writing in Hebrew, as well as in Russian. In 1883, when he was 24 years old, he published his first Yiddish story, צוויי שטיינער Tsvey Shteyner ("Two Stones"), using for the first time the pseudonym Sholem Aleichem.

By 1890 he was a central figure in Yiddish literature, the vernacular language of nearly all East European Jews, and produced over forty volumes in Yiddish. It was often derogatorily called "jargon", but Sholem Aleichem used this term in an entirely non-pejorative sense.

Apart from his own literary output, Sholem Aleichem used his personal fortune to encourage other Yiddish writers. In 1888–89, he put out two issues of an almanac, די ייִדיש פאָלק ביבליאָטעק Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek ("The Yiddish Popular Library") which gave important exposure to young Yiddish writers.

In 1890, after he lost his entire fortune, he could not afford to print the almanac's third issue, which had been edited but was subsequently never printed.

Tevye the Dairyman, in Yiddish טבֿיה דער מילכיקער Tevye der Milchiger, was first published in 1894.

Over the next few years, while continuing to write in Yiddish, he also wrote in Russian for an Odessa newspaper and for Voskhod, the leading Russian Jewish publication of the time, as well as in Hebrew for Ha-melitz, and for an anthology edited by YH Ravnitzky. It was during this period that Sholem Aleichem contracted tuberculosis.

In August 1904, Sholem Aleichem edited הילף : א זאמעל-בוך פיר ליטעראטור אונ קונסט Hilf: a Zaml-Bukh fir Literatur un Kunst ("Help: An Anthology for Literature and Art"; Warsaw, 1904) and himself translated three stories submitted by Tolstoy (Esarhaddon, King of Assyria; Work, Death and Sickness; The Three Questions) as well as contributions by other prominent Russian writers, including Chekhov, in aid of the victims of the Kishinev pogrom.

Critical reception

Sholem Aleichem's narratives were notable for the naturalness of his characters' speech and the accuracy of his descriptions of shtetl life. Early critics focused on the cheerfulness of the characters, interpreted as a way of coping with adversity. Later critics saw a tragic side in his writing.[13] He was often referred to as the "Jewish Mark Twain" because of the two authors' similar writing styles and use of pen names. Both authors wrote for adults and children and lectured extensively in Europe and the United States. When Twain heard of the writer called "the Jewish Mark Twain," he replied "please tell him that I am the American Sholem Aleichem."[14]

Beliefs and activism

Sholem Aleichem was an impassioned advocate of Yiddish as a national Jewish language, which he felt should be accorded the same status and respect as other modern European languages. He did not stop with what came to be called "Yiddishism", but devoted himself to the cause of Zionism as well. Many of his writings[15] present the Zionist case. In 1888, he became a member of Hovevei Zion. In 1907, he served as an American delegate to the Eighth Zionist Congress held in The Hague.

Sholem Aleichem had a mortal fear of the number 13. His manuscripts never had a page 13; he numbered the thirteenth pages of his manuscripts as 12a.[16] Though it has been written that even his headstone carries the date of his death as "May 12a, 1916",[17] his headstone reads the dates of his birth and death in Hebrew, the 26th of Adar and the 10th of Iyar, respectively.

Death

Sholem Aleichem died in New York on May 13, 1916 from tuberculosis and diabetes,[18] aged 57, while working on his last novel, Motl, Peysi the Cantor's Son, and was buried at Old Mount Carmel cemetery in Queens.[19] At the time, his funeral was one of the largest in New York City history, with an estimated 100,000 mourners.[20][21] The next day, his will was printed in the New York Times and was read into the Congressional Record of the United States.

Commemoration and legacy

Sholem Aleichem's will contained detailed instructions to family and friends with regard to burial arrangements and marking his yahrtzeit.

He told his friends and family to gather, "read my will, and also select one of my stories, one of the very merry ones, and recite it in whatever language is most intelligible to you." "Let my name be recalled with laughter," he added, "or not at all." The celebrations continue to the present day, and, in recent years, have been held at the Brotherhood Synagogue on Gramercy Park South in New York City, where they are open to the public.[22]

He composed the text to be engraved on his tombstone in Yiddish:

- Do ligt a Id a posheter - Here lies a Jew a simple-one,

- Geshriben Idish-Daitsh far vayber - Wrote Yiddish-German (translations) for women

- Un faren prosten folk hot er geven a humorist a shrayber

- - and for the regular folk, was a writer of humor

- Di gantse lebn umgelozt geshlogen mit der welt kapores

- -His whole life he slaughtered ritual chickens together with the crowd,

- (He didn't care too much for this world)

- Di gantse welt hot gut gemacht - the whole world does good,

- Un er - oy vey - geveyn oyf tsores - and he, oh my, is in trouble.

- Un davka de mol geven der oylem hot gelacht

- - but exactly when the world is laughing

- geklutched un fleg zich fleyen - clapping and hitting their lap,

- Doch er gekrenkt dos veys nor got - he cries - only God knows this

- Besod, az keyner zol nit zeen - in secret, so no-one sees.

In 1997, a monument dedicated to Sholem Aleichem was erected in Kyiv; another was erected in 2001 in Moscow.

The main street of Birobidzhan is named after Sholem Aleichem;[23] streets were named after him also in other cities in the Soviet Union, most notably among them in Ukrainian cities such as Kyiv, Odessa, Vinnytsia, Lviv, and Zhytomyr. In New York City in 1996, East 33rd Street between Park and Madison Avenue is additionally named "Sholem Aleichem Place". Many streets in Israel are named after him.

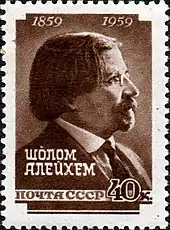

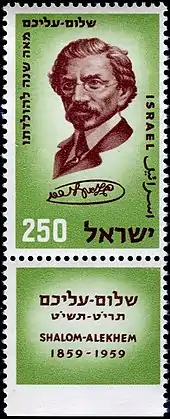

Postage stamps of Sholem Aleichem were issued by Israel (Scott #154, 1959); the Soviet Union (Scott #2164, 1959); Romania (Scott #1268, 1959); and Ukraine (Scott #758, 2009).

An impact crater on the planet Mercury also bears his name.[24]

On March 2, 2009 (150 years after his birth) the National Bank of Ukraine issued an anniversary coin celebrating Aleichem with his face depicted on it.[25]

Vilnius, Lithuania has a Jewish school named after him and in Melbourne, Australia a Yiddish school, Sholem Aleichem College is named after him.[26] Several Jewish schools in Argentina were also named after him.

In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil a library named BIBSA – Biblioteca Sholem Aleichem was founded in 1915 as a Zionist institution but some years later Jews of left-wing assumed the power by regular internal polls, and Sholem Aleichem started to mean Communism in Rio de Janeiro. BIBSA had a very active theatrical program in Yiddish for more than 50 years since its foundation and of course Sholem Aleichem scripts were a must. In 1947 BIBSA evolved in a more complete club named ASA – Associação Sholem Aleichem that exists nowadays in Botafogo neighborhood. Next year, in 1916 same group that created BIBSA, founded a Jewish school named Escola Sholem Aleichem that was closed in 1997. It was Zionist too, and became Communist like BIBSA, but after the 20th Communist Congress in 1956 school supporters and teachers split as a lot of Jews abandoned Communism and founded another school, Colégio Eliezer Steinbarg, still existing as one of the best Jewish schools in Brazil, named after the first director of Sholem Aleichem School, he himself, a Jewish writer born in Romania, that came to Brazil.[27][28]

In the Bronx, New York, a housing complex called The Shalom Aleichem Houses[29] was built by Yiddish speaking immigrants in the 1920s, and was recently restored by new owners to its original grandeur. The Shalom Alecheim Houses are part of a proposed historic district in the area.

On May 13, 2016 a Sholem Aleichem website was launched to mark the 100th anniversary of Sholem Aleichem's death.[30] The website is a partnership between Sholem Aleichem's family,[31] his biographer Professor Jeremy Dauber,[32] Citizen Film, Columbia University's Center for Israel and Jewish Studies,[33] The Covenant Foundation, and The Yiddish Book Center.[34] The website features interactive maps and timelines,[35] recommended readings,[36] as well as a list of centennial celebration events taking place worldwide.[37] The website also features resources for educators.[38][39][40]

Sholem Aleichem's granddaughter, Bel Kaufman, by his daughter Lala (Lyalya), was an American author, most widely known for her novel, Up the Down Staircase, published in 1964, which was adapted to the stage and also made into a motion picture in 1967, starring Sandy Dennis.

Published works

English-language collections

- Tevye's Daughters: Collected Stories of Sholom Aleichem by Sholem Aleichem, transl Frances Butwin, illus Ben Shahn, NY: Crown, 1949. The stories which form the basis for Fiddler on the Roof.

- The Best of Sholom Aleichem, edited by R. Wisse, I. Howe (originally published 1979), Walker and Co., 1991, ISBN 0-8027-2645-3.

- Tevye the Dairyman and the Railroad Stories, translated by H. Halkin (originally published 1987), Schocken Books, 1996, ISBN 0-8052-1069-5.

- Nineteen to the Dozen: Monologues and Bits and Bobs of Other Things, translated by Ted Gorelick, Syracuse Univ Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8156-0477-7.

- A Treasury of Sholom Aleichem Children's Stories, translated by Aliza Shevrin, Jason Aronson, 1996, ISBN 1-56821-926-1.

- Inside Kasrilovka, Three Stories, translated by I. Goldstick, Schocken Books, 1948 (variously reprinted)

- The Old Country, translated by Julius & Frances Butwin, J B H of Peconic, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-21-2.

- Stories and Satires, translated by Curt Leviant, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-20-4.

- Selected Works of Sholem-Aleykhem, edited by Marvin Zuckerman & Marion Herbst (Volume II of "The Three Great Classic Writers of Modern Yiddish Literature"), Joseph Simon Pangloss Press, 1994, ISBN 0-934710-24-4.

- Some Laughter, Some Tears, translated by Curt Leviant, Paperback Library, 1969, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 68–25445.

Autobiography

- Funem yarid, written 1914–1916, translated as The Great Fair by Tamara Kahana, Noonday Press, 1955; translated by Curt Leviant as From the Fair, Viking, 1986, ISBN 0-14-008830-X.

Novels

- Stempenyu, originally published in his Folksbibliotek, adapted 1905 for the play Jewish Daughters.

- Yossele Solovey (1889, published in his Folksbibliotek)

- Tevye's Daughters, translated by F. Butwin (originally published 1949), Crown, 1959, ISBN 0-517-50710-2.

- Mottel the Cantor's son. Originally written in Yiddish. English version: Henry Schuman, Inc. New York 1953

- In The Storm

- Wandering Stars

- Marienbad, translated by Aliza Shevrin (1982, G.P. Putnam Sons, New York) from original Yiddish manuscript copyrighted by Olga Rabinowitz in 1917

- The Bloody Hoax

- Menahem-Mendl, translated as The Adventures of Menahem-Mendl, translated by Tamara Kahana, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1969, ISBN 1-929068-02-6.

Young adult literature

- The Bewitched Tailor, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-19-0.

Plays

- The Doctor (1887), one-act comedy

- Der get (The Divorce, 1888), one-act comedy

- Di asife (The Assembly, 1889), one-act comedy

- Mazel Tov (1889), one-act play

- Yaknez (1894), a satire on brokers and speculators

- Tsezeyt un tseshpreyt (Scattered Far and Wide, 1903), comedy

- Agentn (Agents, 1908), one-act comedy

- Yidishe tekhter (Jewish Daughters, 1905) drama, adaptation of his early novel Stempenyu

- Di goldgreber (The Golddiggers, 1907), comedy

- Shver tsu zayn a yid (Hard to Be a Jew / If I Were You, 1914)

- Dos groyse gevins (The Big Lottery / The Jackpot, 1916)

- Tevye der milkhiker, (Tevye the Milkman, 1917, performed posthumously)

Miscellany

- Jewish Children, translated by Hannah Berman, William Morrow & Co, 1987, ISBN 0-688-84120-1.

- numerous stories in Russian, published in Voskhod (1891–1892)

References

- "Heroes – Trailblazers of the Jewish People". Beit Hatfutsot.

- The parallel greeting in Arabic is السَّلَامُ عَلَيْكُمْ [ʔæs.sæˈlæːmu ʕæˈlæjkʊm] (As-salamu alaykum).

- Potok, Chaim (July 14, 1985). "The Human Comedy Of Pereyaslav". New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

Approaching his 50th birthday, the Yiddish writer Sholom Aleichem (born Sholom Rabinowitz in the Ukraine in 1859) collapsed in Russia while on a reading tour. He was diagnosed as suffering from tuberculosis. As he put it later, 'I had the privilege of meeting his majesty, the Angel of Death, face to face.'

- "Aleichem", Jewish virtual library (biography).

- Aleichem, Sholem (1985), "34. Cholera", From the Fair, Viking Penguin, pp. 100–4.

- Dates on base of Rabinowitz's gravestone.

- Kaplan Appel, Tamar (August 3, 2010). "Crown Rabbi". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300119039. OCLC 170203576. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- Huttner, Jan Lisa (September 18, 2014). Tevye's Daughters: No Laughing Matter. New York City, NY: FF2 Media. ASIN B00NQDQCTG. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- First Yiddish Language Conference. Two roads to Yiddishism (Nathan Birnbaum and Sholem Aleichem) by Louis Fridhandler

- Guide to the Sutzkever Kaczerginski Collection, Part II: Collection of Literary and Historical Manuscripts RG 223.2, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research,

- Sholom Aleichem Panorama, I. D. Berkowitz, translator, M. W. (Melech) Grafstein, editor and publisher, (London, Ontario, Canada: The Jewish Observer, 1948), pp. 343-344

- Wilson, Scott (August 22, 2016). Resting places: the burial sites of more than 14,000 famous persons (Third ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina. p. 14. ISBN 978-0786479924. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- "Sholom Aleichem Aleichem, Sholom – Essay – eNotes.com". eNotes. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- Levy, Richard S. Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO 2005 sv Twain; cites Kahn 1985 p 24

- Oyf vos badarfn Yidn a land, (Why Do the Jews Need a Land of Their Own? Archived March 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine), translated by Joseph Leftwich and Mordecai S. Chertoff, Cornwall Books, 1984, ISBN 0-8453-4774-8

- "A Reading to Recall the Father of Tevye", Clyde Haberman, New York Times, May 17, 2010

- Hendrickson, Robert (1990). World Literary Anecdotes. New York, New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 7. ISBN 0-8160-2248-8.

- Donaldson, Norman and Betty (1980). How Did They Die?. Greenwich House. ISBN 0-517-40302-1.

- Mount Carmel cemetery Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Vast Crowds Honor Sholem Aleichem; Funeral Cortege Of Yiddish Author Greeted By Throngs In Three Boroughs. Many Deliver Eulogies Services At Educational Alliance Include Reading Of Writer's Will And His Epitaph". New York Times. May 16, 1916. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

A hundred thousand people of the East Side, with sadness in their faces, lined the sidewalks yesterday when the funeral procession of Sholem Aleichem ("peace be with you"), the famous Yiddish humorist, whose real name was Solomon Rabinowitz, passed down Second Avenue and through East Houston. Eldridge, and Canal Streets, to the Educational Alliance, where services were held before the body was carried over the Williamsburg Bridge to ...

- "2,500 Jews Mourn Sholem Aleichem; "Plain People" Honor Memory Of "Jewish Mark Twain" In Carnegie Hall. Some Of His Stories Read Audience Laughs Through Tears, Just As The Author Had Said He Hoped Friends Would Do". New York Times. May 18, 1916. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

More than 2,500 Jews paid honor to the memory of Sholem Aleichem, the "Mark Twain, who depicted in a style almost epic" the spirit of his race, at a "mourning evening" in Carnegie Hall last night.

- Haberman, Clyde. A Reading to Recall the Father of Tevye. The New York Times. May 17, 2010.

- Raskin, Rebecca. "Back to Birobidjan". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- MESSENGER: MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging Archived September 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Events by themes: To 150th years from the birthday of Sholom-Aleichem NBU issued an anniversary coin, UNIAN photo service (March 2, 2009)

- "Sholem Aleichem College". www.sholem.vic.edu.au. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Eliezer Max". www.eliezermax.com.br. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Colégio Liessin". Colégio Liessin. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "SHALOM ALEICHEM HOUSES – Historic Districts Council's Six to Celebrate". www.6tocelebrate.org. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "The Ethical Will". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Sholom Aleichem: The Next Generation". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- Raphael, Frederic (December 20, 2013). "Book Review: 'The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem' by Jeremy Dauber". Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via www.wsj.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "About this site" Sholem Aleichem. sholemaleichem.org. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "Life & Times – Sholem Aleichem". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Recommended Reading – Sholem Aleichem". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Events – Sholem Aleichem". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Student Activities – Sholem Aleichem". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Syllabi – Sholem Aleichem". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "Call to Action – Sholem Aleichem". Retrieved June 12, 2017.

Further reading

- My Father, Sholom Aleichem, by Marie Waife-Goldberg

- Tradition!: The Highly Improbable, Ultimately Triumphant Broadway-to-Hollywood Story of Fiddler on the Roof, the World's Most Beloved Musical, by Barbara Isenberg, (St. Martin's Press, 2014.)

- Liptzin, Sol, A History of Yiddish Literature, Jonathan David Publishers, Middle Village, NY, 1972, ISBN 0-8246-0124-6. 66 et. seq.

- A Bridge of Longing, by David G. Roskies

- The World of Sholom Aleichem, by Maurice Samuel

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sholom Aleichem. |

- The Official Sholem Aleichem Website

- Works by Sholem Aleichem at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sholem Aleichem at Internet Archive

- Works by Sholem Aleichem at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Haaretz article A stenographer for his people's soul

- The complete works of Sholem Aleichem (searchable and editable; Yiddish letters only).