Shuka

Shuka[1][2] (Sanskrit: शुक IAST: Śuka, also Shukadeva Śuka-deva) is a rishi (sage) in Hinduism. He is the son of the sage Vyasa and the main narrator of the scripture Bhagavata Purana. Most of the Bhagavata Purana consists of Shuka reciting the story to the dying king Parikshit. Shuka is depicted as a sannyasi, renouncing the world in pursuit of moksha (liberation), which most narratives assert that he achieved.[3]

| Shuka | |

|---|---|

| Mahabharata character | |

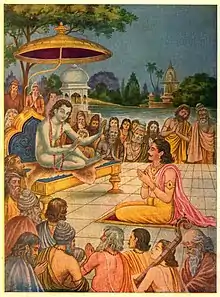

Shuka preaching to Parikshit and the sages | |

| In-universe information | |

| Family | Vyasa (father) Vatikā (mother) |

| Spouse | Pivari |

Legends

According to the Hindu epic Mahabharata, after one hundred years of austerity by Vyasa, Shuka was churned out of a stick of fire, born with ascetic power and with the Vedas dwelling inside him, just like his father. As per Skanda Purana, Vyasa had a wife, Vatikā (alias Pinjalā), daughter of a sage named Jābāli. Their union produced a son, who repeated everything what he heard, thus receiving the name Shuka (lit. Parrot).[4][5][6] Other texts including the Devi Bhagavata Purana also narrate the birth of Shuka but with drastic differences. Vyasa was desiring an heir, when an apsara (celestial damsel) named Ghritachi flew in front of him in form of a beautiful parrot, causing him sexual arousal. He discharges his semen, which fell on some sticks and a son developed. This time, he was named Shuka because of the role of the celestial parrot.[7]

The Mahabharata also recounts how Shuka was sent by Vyasa for training to King Janaka, who was considered to be a Jivanmukta or one who is liberated while still in a body. Shuka studied under the guru of the gods, Brihaspati and Vyasa. Shuka asked Janaka about the way to liberation, with Janaka recommending the traditional progression of the four ashramas, which included the householder stage. After expressing contempt for the householder's life, Shuka questioned Janaka about the real need for following the householder's path. Seeing Shuka's advanced state of realization, Janaka told him that there was no need in his case.[8]

Stories recount how Shuka surpassed his father in spiritual attainment. Once, when following his son, Vyasa encountered a group of celestial nymphs who were bathing. Shuka's purity was such that the nymphs did not consider him to be a distraction, even though he was naked, but covered themselves when faced with his father.[9][10] Shuka is sometimes portrayed as wandering about naked, due to his complete lack of self-consciousness.[11]

A completely different version of the later life of Shuka is given in the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, considered a secondary Purana (upapurana) by many, but important work in the Shakta tradition. In this account, Shuka is convinced by Janaka to follow the ashrama tradition and returns home to marry and follow the path of yoga. He has five children with his wife Pivari—four sons and a daughter. The story concludes in the same vein as the common tradition, with Shuka achieving moksha.[12]

Later, Shuka told a brief version of the Bhagavata Purana to the Kuru king Parikshit, who was destined to die within few days due to a curse.

A place called Shukachari is believed to be the cave of Shuka, where he disappeared in cave stones as per local traditions. Shuka in Sanskrit means parrot and thus the name is derived from the large number of parrots found around the Shukachari hills. Shukachari literally means abode of parrots in the Sanskrit language.

Further reading

- Shuka. In: Wilfried Huchzermeyer: Studies in the Mahabharata. Indian Culture, Dharma and Spirituality in the Great Epic. Karlsruhe 2018, ISBN 978-3-931172-32-9, pp. 164–178

References

- Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: the relationship between Krishna and Vishnu. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2001). Rethinking the Mahābhārata: a reader's guide to the education of the dharma king. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34054-8.

- Sullivan, Bruce M. (1990). Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa and the Mahābhārata: a new interpretation. BRILL. p. 40. ISBN 978-90-04-08898-6.

- Dalal, Roshen (6 January 2019). The 108 Upanishads: An Introduction. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. ISBN 978-93-5305-377-2.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (1 September 2000). The Goddess in India: The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59477-537-6.

- Skanda Purāṇa, Nāgara Khanda, ch. 147

- https://archive.org/stream/puranicencyclopa00maniuoft#page/885/mode/1up

- Gier, Nicholas F. (2000). Spiritual Titanism: Indian, Chinese, and Western perspectives. SUNY series in constructive postmodern thought. SUNY Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-7914-4527-3.

- Venkatesananda, S. (1989). The Concise Srimad Bhagavatam. State University of New York Press.

- Purdy, S.B. (2006). "Whitman and the (National) Epic: a Sanskrit Parallel". Revue Française d Études Américaines. 108 (2006/2): 23–32. doi:10.3917/rfea.108.0023. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- Prabhavananda, Swami (1979) [1962]. Spiritual Heritage of India. Vedanta Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-87481-035-6.

- Fort, Andrew O.; Patricia Y. Mumme (1996). Living liberation in Hindu thought. SUNY Press. pp. 170–173. ISBN 978-0-7914-2705-7.