Kapila

Kapila (Sanskrit: कपिल) is a given name of different individuals in ancient and medieval Indian texts, of which the most well known is the founder of the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy.[1][2] Kapila of Samkhya fame is considered a Vedic sage,[2][3] estimated to have lived in the 6th-century BCE,[4] or the 7th-century BCE.[5]

Kapila | |

|---|---|

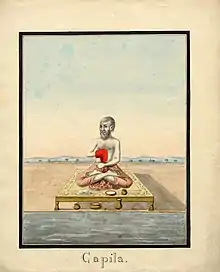

Watercolour painting on paper of Kapila, a sage | |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Parents | Devahuti (mother), Maharishi Kardama (father) |

| Philosophy | Samkhya |

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

Rishi Kapila is credited with authoring the influential Samkhya-sutra, in which aphoristic sutras present the dualistic philosophy of Samkhya.[6] Kapila's influence on Buddha and Buddhism have long been the subject of scholarly studies.[7][8]

Many historic personalities in Hinduism and Jainism, mythical figures, pilgrimage sites in Indian religion, as well as an ancient variety of cow went by the name Kapila.[5][9][10]

Biography

The name Kapila appears in many texts, and it is likely that these names refer to different people.[11][12] The most famous reference is to the sage Kapila with his student Āsuri, who in the Indian tradition, are considered as the first masters of Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy. While he pre-dates Buddha, it is unclear which century he lived in, with some suggesting 6th-century BCE.[4] Others place him in the 7th century BCE.[11][13] This places him in the late Vedic period (1500 BCE to 500 BCE), and he has been called a Vedic sage.[2][3]

Kapila is credited with authoring an influential sutra, called Samkhya-sutra (also called Kapila-sutra), which aphoristically presents the dualistic philosophy of Samkhya.[6][14] These sutras were explained in another well studied text of Hinduism called the Samkhyakarika.[11] Beyond the Samkhya theories, he appears in many dialogues of Hindu texts, such as in explaining and defending the principle of Ahimsa (non-violence) in the Mahabharata.[1]

Hinduism

The name Kapila is used for many individuals in Hinduism, few of which may refer to the same person.

In Vedic texts

The Rigveda X.27.16 mentions Kapila (daśānām ekam kapilam) which the 14th-century Vedic commentator Sayana thought refers to a sage; a view which Chakravarti in 1951 and Larson in 1987 consider unreliable, with Chakravarti suggesting that the word refers to one of the Maruts,[15] while Larson and Bhattacharya state kapilam in that verse means "tawny" or "reddish-brown";[16] as was also translated by Griffith.[note 1]

The Śata-piṭaka Series on the Śākhās of the Yajurveda – estimated to have been composed between 1200 and 1000 BCE[19] – mention of a Kapila Śākhā situated in the Āryāvarta, which implies a Yajurveda school was named after Kapila.[16] The term Kapileya, meaning "clans of Kapila", occurs in the Aitareya Brahmana VII.17 but provides no information on the original Kapila.[note 2] The pariśiṣṭa (addenda) of the Atharvaveda (at XI.III.3.4)[note 3] mentions Kapila, Āsuri and Pañcaśikha in connection with a libation ritual for whom tarpana is to be offered.[16] In verse 5.2 of Shvetashvatara Upanishad, states Larson, both the terms Samkhya and Kapila appear, with Kapila meaning color as well as a "seer" (Rishi) with the phrase "ṛṣiṃ prasūtaṃ kapilam ... tam agre.."; which when compared to other verses of the Shvetashvatara Upanishad Kapila likely construes to Rudra and Hiranyagarbha.[16] However, Max Muller is of view that Hiranyagarbha, namely Kapila in this context, varies with the tenor of the Upanishad, was distinct and was later used to link Kapila and assign the authorship of Sankya system to Hiranyagarbha in reverence for the philosophical system.[22]

In the Puranas

Kapila, states George Williams, lived long before the composition of the Epics and the Puranas, and his name was coopted in various later composed mythologies.[23]

- As an ascetic and as sleeping Vishnu: In the Brahma Purana, when the evil king Vena abandoned the Vedas, declared that he was the only creator of dharma, and broke all limits of righteousness,[24] and was killed, Kapila advises hermits to churn Vena's thigh from which emerged Nishadas, and his right hand from which Prthu originated who made earth productive again. Kapila and hermits then went to Kapilasangama, a holy place where rivers meet.[25] The Brahma Purana also mentions Kapila in the context of Sagara's 60,000 sons who looking for their Ashvamedha horse, disturbed Vishnu who was sleeping in the shape of Kapila. He woke up, the brilliance in his eyes burnt all but four of Sagara's sons to ashes, leaving few survivors carrying on the family lineage.[26] Sagara's son was King Dilip and his grandson was Bhagiratha. On the advice of his guru Trithala, Bhagiratha did penance for a thousand years (according to god timeline) to please Ganga, to gain the release his 60,000 great-uncles from the curse of saint Kapila.

- As Vishnu's incarnation: The Narada Purana enumerates two Kapilas, one as the incarnation of Brahma and another as the incarnation of Vishnu. The Puranas Bhagavata, Brahmanda, Vishnu, Padma, Skanda, Narada Purana; and the Valmiki Ramayana mentions Kapila is an incarnation of Vishnu. The Padma Purana and Skanda Purana conclusively call him Vishnu himself who descended on earth to disseminate true knowledge. Bhagavata Purana calls him Vedagarbha Vishnu. The Vishnusahasranama mentions Kapila as a name of Vishnu. In his commentary on the Samkhyasutra, Vijnanabhikshu mentions Kapila, the founder of Samkhya system, is Vishnu. Jacobsen suggests Kapila of the Veda, Śramaṇa tradition and the Mahabharata is the same person as Kapila the founder of Samkhya; and this individual is considered as an incarnation of Vishnu in the Hindu texts.[27]

- As son of Kardama muni: The Book 3 of the Bhagavata Purana,[28][29] states Kapila was the son of Kardama Prajapati and his wife Devahuti. Kardama was born from Chaya, the reflection of Brahma. Brahma asks Kardama to procreate upon which Kardama goes to the banks of Sarasvati river, practices penance, visualizes Vishnu and is told by Vishnu that Manu, the son of Brahma will arrive there with his wife Shatarupa in search of a groom for their daughter Devahuti. Vishnu advises Kardama to marry Devahuti, and blesses Kardama that he himself will be born as his son. Besides Kapila as their only son, Kardama and Devahuti had nine daughters, namely Kala, Anusuya, Sraddha, Havirbhu, Gita, Kriya, Khyati, Arundhati and Shanti who were married to Marici, Atri, Angiras, Pulastya, Pulaha, Kratu, Bhrigu, Vashistha, and Atharvan respectively. H.H.Wilson notes the Bhagavatha adds a third daughter Devahuti to introduce the long legend of Kardama, and of their son Kapila, an account not found elsewhere.[30] Kapila is described, states Daniel Sheridan, by the redactor of the Purana, as an incarnation of the supreme being Vishnu, in order to reinforce the Purana teaching by linking it to the traditional respect to Kapila's Samkhya in Hinduism.[28] In the Bhagavata Purana, Kapila presents to his mother Devahuti, the philosophy of yoga and theistic dualism.[28] Kapila's Samkhya is also described through Krishna to Uddhava in Book 11 of the Bhagavata Purana, a passage also known as the "Uddhava Gita".[28]

- As son of Kashyapa: The Matsya Purana mentions Kapila as the son of Kashyapa from his wife Danu, daughter of Daksha Prajapati. Kapila was one among Danu's 100 sons, and her other sons (Kapila's brothers) mentioned in the Vishnu Purana include Dvimurddha, Shankara, Ayomukha, Shankhushiras, Samvara, Ekachakra, Taraka, Vrishaparvan, Svarbhanu, Puloman, Viprachitti and other Danavas.[31]

- As son of Vitatha or Bharadwaja: In the Brahma Purana[32] and in the Harivamsa[33] Kapila was the son of Vitatha. Daniélou translates Vitatha to inaccuracy;[33] and Wilson notes Bharadwaja was also named Vitatha (unprofitable);[32] while he was given in adoption to Bharata. Vishnu Purana notes Bhavanmanyu was the son of Vitatha but Brahma Purana and Harivamsa omit this and make Suhotra, Anuhotra, Gaya, Garga, and Kapila the sons of Vitatha.[32] The Brahma Purana differs from other puranas in saying Vitatha was the son of Bharadwaja; and upon the death of Bharata, Bharadwaja installed Vitatha as the king, before leaving for the forest.[34]

In the Dharmasutras and other texts

Fearlessness to all living beings from my side,

Svāhā!

—Kapila, Baudhayana Grihya Sutra, 4.16.4[35]

Translators: Jan E. M. Houben, Karel Rijk van Kooij

- As son of Prahlada: The Baudhayana Dharmasutra mentions the Asura[note 4] Kapila was the son of Prahlada in the chapter laying rules for the Vaikhanasas.[note 5] The section IV.16 of Baudhāyana Gṛhyasūtra mentions Kapila as the one who set up rules for ascetic life.[16] Kapila is credited, in the Baudhayana Dharmasutra, with creating the four Ashrama orders: brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha and sanyassa, and suggesting that renouncer should never injure any living being in word, thought or deed.[35] He is said to have made rules for renouncement of the sacrifices and rituals in the Vedas, and an ascetic's attachment instead to the Brahman.[38][note 6] In other Hindu texts such as the Mahabharata, Kapila is again the sage who argues against sacrifices, and for non-violence and an end to cruelty to animals, with the argument that if sacrifices benefited the animal, then logically the family who sacrifices would benefit by a similar death.[1] According to Chaturvedi, in a study of inscriptions of Khajuraho temples, the early Samkhya philosophers were possibly disciples of female teachers.[note 7]

Imagery in the Agamas

Kapila's imagery is depicted with a beard, seated in padmāsana with closed eyes indicating dhyāna, with a jaṭā-maṇḍala around the head, showing high shoulders indicating he was greatly adept in controlling breath, draped in deer skin, wearing the yagñopavīta, with a kamaṇḍalu near him, with one hand placed in front of the crossed legs, and feet marked with lines resembling outline of a lotus. This Kapila is identified with Kapila the founder of Sāṅkhya system;[40] while the Vaikhānasasāgama gives somewhat varying description. The Vaikhānasasāgama places Kapila as an āvaraņadēvāta and allocates the south-east corner of the first āvaraņa.[40] As the embodiment of the Vedas his image is seated facing east with eight arms; of which four on the right should be in abhaya mudra, the other three should carry the Chakra, Khaḍga, Hala; one left hand is to rest on the hip in the kațyavarlambita pose and other three should carry the Ṡaṅkha, Pāśa and Daṇḍa.[40]

Other descriptions

- The name Kapila is sometimes used as an epithet for Vasudeva with Vasudeva having incarnated in the place named Kapila.[41]

- Pradyumna assumed the form of Kapila when he became free from desire of worldly influences.[40]

- Kapila is as one of the seven Dikpalas with the other 6 being Dharma, Kala, Vasu, Vasuki, Ananta.

- The Jayakhya Samhita of 5th century AD alludes to the Chaturmukha Vishnu of Kashmir and mentions Vishnu with Varaha, Nrsimha and Kapila defeated the asuras who appeared before them in zoomorphic forms with Nrsimha and Varaha posited to be incarnations of Vishnu and Kapila respectively.[42]

- In the Vamana Purana, the Yakshas were sired by Kapila with his consort Kesini who was from the Khasa class; though the epics attribute the origin of Yakshas to a cosmic egg or to the sage Pulastya; while other puranas posit Kashyapa as the progenitor of Yakshas with his consort Vishva or Khasha.[43]

- In some puranas, Kapila is also mentioned as a female, a daughter of Khaśā and a Rākșasī, after whom came the name Kāpileya gaņa.[44] In the Mahabharat, Kapila was a daughter of Daksha [note 8] and having married Kashyapa gave birth to the Brahmanas, Kine, Gandharvas and Apsaras.[45]

- Kapila being a great teacher also had gardening as a hobby focusing his time around the babool (Acacia) tree everywhere he lived.https://theharekrishnamovement.org/category/teachings-of-lord-kapila/

Jainism

Kapila is mentioned in chapter VIII of the Uttaradhyayana-sutra, states Larson and Bhattacharya, where a discourse of poetical verses is titled as Kaviliyam, or "Kapila's verses".[16]

The name Kapila appears in Jaina texts. For example, in the 12th century Hemacandra's epic poem on Jain elders, Kapila appears as a Brahmin who converted to Jainism during the Nanda Empire era.[10]

According to Jnatadharmakatha, Kapila was a contemporary of Krishna and the Vasudeva of Dhatakikhanda. The text further mentions that both of them blew their shankha (counch) together.[47]

Buddhism

Buddhists literature, such as the Jataka tales, state the Buddha was Kapila in one of his previous lives.[48][49][50]

Scholars have long compared and associated the teachings of Kapila and Buddha. For example, Max Muller wrote (abridged),

There are no doubt certain notions which Buddha shares in common, not only with Kapila, but with every Hindu philosopher. (...) It has been said that Buddha and Kapila were both atheists, and that Buddha borrowed his atheism from Kapila. But atheism is an indefinite term, and may mean very different things. In one sense, every Indian philosopher was an atheist, for they all perceived that the gods of the populace could not claim the attributes that belong to a Supreme Being (Absolute, the source of all that exists or seems to exist, Brahman). (...) Kapila, when accused of atheism, is not accused of denying the existence of an Absolute Being. He is accused of denying the existence of an Ishvara.

— Max Muller et al., Studies in Buddhism[7]

Max Muller states the link between the more ancient Kapila's teachings on Buddha can be overstated.[7] This confusion is easy, states Muller, because Kapila's first sutra in his classic Samkhya-sutra, "the complete cessation of pain, which is of three kinds, is the highest aim of man", sounds like the natural inspiration for Buddha.[7] However, adds Muller, the teachings on how to achieve this, by Kapila and by Buddha, are very different.[7]

As Buddhist art often depicts Vedic deities, one can find art of both Narayana and Kapila as kings within a Buddhist temple, along with statues of Buddhist figures such as Amitabha, Maitreya, and Vairocana.[51]

In Chinese Buddhism, the Buddha directed the Yaksha Kapila and fifteen daughters of Devas to become the patrons of China.[52]

Works

The following works were authored by Kapila, some of which are lost, and known because they are mentioned in other works; while few others are unpublished manuscripts available in libraries stated:

- Manvadi Shrāddha - mentioned by Rudradeva in Pakayajna Prakasa.

- Dṛṣṭantara Yoga - also named Siddhāntasāra available at Madras Oriental Manuscripts Library.

- Kapilanyayabhasa - mentioned by Alberuni in his works.

- Kapila Purana - referred to by Sutasamhita and Kavindracharya. Available at Sarasvati Bhavana Library, Varanasi.

- Kapila Samhita - there are 2 works by the same name. One is the samhita quoted in the Bhagavatatatparyanirnaya and by Viramitrodaya in Samskaras. Another is the Samhita detailing pilgrim centers of Orissa.

- Kapilasutra - Two books, namely the Samkya Pravacana Sutra and the Tattvasamasasutra, are jointly known as Kapilasutra. Bhaskararaya refers to them in his work Saubhagya-bhaskara.

- Kapila Stotra - Chapters 25 to 33 of the third khanda of the Bhagavata Mahapurana are called Kapila Stotra.

- Kapila Smriti - Available in the work Smriti-Sandarbha, a collection of Smritis, from Gurumandal Publications.

- Kapilopanishad - Mentioned in the Anandasrama list at 4067 (Anandasrama 4067).

- Kapila Gita - also known as Dṛṣṭantasara or Siddhāntasāra.

- Kapila Pancharatra - also known as Maha Kapila Pancharatra. Quoted by Raghunandana in Saṃskāra Mayukha.

Ayurveda books mentioning Kapila's works are:

- Vagbhatta mentions Kapila's views in chapter 20 of Sutrasthana.

- Nischalakara mentions Kapila's views in his commentary on Chikitsa Sangraha.

- Kapila's views are quoted in Ayurvedadipika.

- The Kavindracharya list at 987 mentions a book named Kapila Siddhanta Rasayana.

- Hemadri quotes Kapila's views in Ashtangahradaya (16th verse) of the commentary Ayurveda Rasayana.

- Sarvadarsanasamgraha (Sarva-darśana-saṃgraha) mentions Kapila's views on Raseśvara school of philosophy.

Teachings

Kapila's Samkhya is taught in various Hindu texts:

- "Kapila states in the Mahabharata, "Acts only cleanse the body. Knowledge, however, is the highest end (for which one strives). When all faults of the heart are cured (by acts), and when the felicity of Brahma becomes established in knowledge, benevolence, forgiveness, tranquillity, compassion, truthfulness, and candour, abstention from injury, absence of pride, modesty, renunciation, and abstention from work are attained. These constitute the path that lead to Brahman. By those one attains to what is the Highest."

- "Bhishma said (to Yudhishthira), 'Listen, O slayer of foes! The Sankhyas or followers of Kapila, who are conversant with all paths and endued with wisdom, say that there are five faults, O puissant one, in the human body. They are Desire and Wrath and Fear and Sleep and Breath. These faults are seen in the bodies of all embodied creatures. Those that are endued with wisdom cut the root of wrath with the aid of Forgiveness. Desire is cut off by casting off all purposes. By cultivation of the quality of Goodness (Sattwa) sleep is conquered, and Fear is conquered by cultivating Heedfulness. Breath is conquered by abstemiousness of diet.

Recognition

Kapila, the founder of Samkhya, has been a highly revered sage in various schools of Hindu philosophy. Gaudapada (~500 CE), an Advaita Vedanta scholar, in his Bhasya called Kapila as one of the seven great sages along with Sanaka, Sananda, Sanatana, Asuri, Vodhu and Pancasikha.[53] Vyasa, the Yoga scholar, in his Yogasutra-bhasya wrote Kapila to be the "primal wise man, or knower".[53]

Notes

- dashAnAmekaM kapilaM samAnaM taM hinvanti kratavepAryAya

garbhaM mAtA sudhitaM vakSaNAsvavenantantuSayantI bibharti [17]

Translated by Griffith as:

One of the ten, the tawny, shared in common, they send to execute their final purpose.

The Mother carries on her breast the Infant of noble form and soothes it while it knows not.[18] - Quote from Chakravarti's work: These Kapileyas are the clans of Kapila, but who was the original Kapila, we cannot know; for the text does not supply us with any further data. In his article on the Śākhās of the Yajurveda, Dr. Raghuvira acquaints us with one Kapila Śākhā that was situated in the Āryāvarta. But we do not know anything else as regards the Kapila with whom the said branch was associated. Further in the khilas of the Rgveda, one Kapila is mentioned along with some other sages. But the account of all these Kapilas is very meagre and hence cannot be much estimated in discussing the attitude of Sāṃkhya Kapila towards the Vedas. Though the Sāṃkhya vehemently criticises the Vedic sacrifices, but thereby it does not totally set aside the validity of the Vedas. In that case it is sure to fall under the category of the nāstika philosophy and could not exercise so much influence upon the orthodox minds; for it is well known that most of the branches of orthodox literature are more or less replete with the praise of Samkhya".[20]

- The pariśiṣṭa to each Veda were composed after the Veda;[21] Atharvaveda itself estimated to have been composed by about 1000 BCE.[19]

- In Vedic texts, Asura refers to any spiritual or divine being.[35] Later, the meaning of Asura contrasts with Deva.[36]

-

Baudhayana Dharma Sutra, Prasna II, Adhyaya 6, Kandika 11, Verses 1 to 34:

14. A hermit is he who regulates his conduct entirely according to the Institutes proclaimed by Vikhanas.(...)

28. With reference to this matter they quote also (the following passage): 'There was, forsooth, an Âsura, Kapila by name, the son of Prahlâda. Striving with the gods, he made these divisions. A wise man should not take heed of them.'[37] - The Baudhayana Dharmasutra Prasna II, Adyaya 6, Kandiaka 11, Verses 26 to 34 dissuade the Vaikhanasas from sacrificial ritual works in the Vedas.[38]

- Quote from p. 49–51: Of course, the Panchatantrikas accorded a place of honour to Kapila who was designated muni and paramarishi, and even identified with Narayana. The original concept of Kapila, the asura exponent of one of the oldest systems of philosophy is, however, preserved in the present inscription. (...) The Rūpamaņḍana and Aparājittapŗichha accounts of the deity mention a female face instead of Kapila which has puzzled scholars. In this connection, it may be pointed out that in the Mahabharata, Pañcaśīkha the disciple of Āsuri has been called Kapileya. He was so named because he was fed on the breast-milk of a brahmana lady, Kapila. According to Chattopadhyaya, "We have to take the story of Kapila breast-feeding Panchasikha ina figurative sense and if we do so the myth might suggest the story of an original female preceptor of the Samkhya system."[39]

- Section LXV of the Sambhava Parva of the Mahabharat states: The daughters of Daksha are, O tiger among men and prince of the Bharata race, Aditi, Diti, Danu, Kala, Danayu, Sinhika, Krodha, Pradha, Viswa, Vinata, Kapila, Muni, and Kadru ... The Brahmanas, kine, Gandharvas, and Apsaras, were born of Kapila as stated in the Purana.[45][46]

References

- Arti Dhand (2009). Woman as Fire, Woman as Sage. State University of New York Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-7914-7988-9. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (1998). The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 731. ISBN 978-0-85229-633-2. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link), Quote:"Kapila (fl. 550 BC), Vedic sage and founder of the system of Samkhya, one of the six schools of Vedic philosophy."

- Guida Myrl Jackson-Laufer (1994). Traditional Epics: A Literary Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-19-510276-5. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016., Quote: "Kapila was a Vedic sage (ca. 550 B.C.) and founder of the Samkhya school of Vedic philosophy.";

John Haldane; Krishna Dronamraju (2009). What I Require From Life. Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19-923770-8. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016. - Kapila Archived 16 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Kapila (James Robert Ballantyne, Translator, 1865), The Sāmkhya aphorisms of Kapila at Google Books, pages 156–157

- Max Muller et al. (1999 Reprint), Studies in Buddhism, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-1226-4, pages 9–10

- W. Woodhill Rockhill (2000 Reprint), The Life of the Buddha and the Early History of His Order, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-37937-6, pages 11–19

- Knut A. Jacobsen (2013). Pilgrimage in the Hindu Tradition: Salvific Space. Routledge. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-415-59038-9. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Hemacandra; R. C. C. Fynes (Translator) (1998). The Lives of the Jain Elders. Oxford University Press. pp. 144–146, Canto Seven, verses 1–19. ISBN 978-0-19-283227-6. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- PT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-139-4, page 304

- Burley, M. (2009). "Kapila: Founder of Samkhya and Avatara of Visnu (with a Translation of Kapilasurisamvada). By Knut A. Jacobsen". The Journal of Hindu Studies. Oxford University Press. 2 (2): 244–246. doi:10.1093/jhs/hip013.

- A. L. Herman (1983). An Introduction to Buddhist Thought: A Philosophic History of Indian Buddhism. University Press of America. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8191-3595-7. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Max Muller et al. (1999 Reprint), Studies in Buddhism, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-1226-4, page 10 with footnote

- Chakravarti, Pulinbihari (1951). Origin and Development of the Sāṃkhya System of Thought (PDF). Oriental Books Reprint Corporation: exclusively distributed by Munshinam Manoharlal Publishers. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Larson, Gerald James; Potter, Karl H.; Bhattacharya, Ram Shankar (1987). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Sāṃkhya, Volume 4 of The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies. Princeton University Press, (Reprint: Motilal Banarsidass). p. 109. ISBN 978-0-691-60441-1.

- "Rig Veda (Sanskrit): Text - IntraText CT". Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "Rig Veda (Griffith tr.): Text - IntraText CT". Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Michael Witzel (2003), "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism (Editor: Gavin Flood), Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-21535-2, pages 68–70

- Chakravarti, Pulinbihari (1951). Origin and Development of the Sāṃkhya System of Thought (PDF). Oriental Books Reprint Corporation: exclusively distributed by Munshinam Manoharlal Publishers. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Moriz Winternitz; V. Srinivasa Sarma (1996). A History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Müller, F.Max (2012). The Upanishads, Part 2. Courier Corporation. p. xxxviii-xli. ISBN 978-0-486-15711-5.

- George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- Söhnen-Thieme, Renate; Söhnen, Renate; Schreiner,Peter (1989). Brahmapurāṇa, Volume 2 of Purāṇa research publications, Tübingen. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 9–10. ISBN 3-447-02960-9. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Söhnen-Thieme, Renate; Söhnen, Renate; Schreiner,Peter (1989). Brahmapurāṇa, Volume 2 of Purāṇa research publications, Tübingen. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 234–235. ISBN 3-447-02960-9. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Söhnen-Thieme, Renate; Söhnen, Renate; Schreiner,Peter (1989). Brahmapurāṇa, Volume 2 of Purāṇa research publications, Tübingen. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 22, 141–142. ISBN 3-447-02960-9. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Jacobsen, Knut A. (2008). Kapila, Founder of Sāṃkhya and Avatāra of Viṣṇu: With a Translation of Kapilāsurisaṃvāda. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Limited. pp. 9–25. ISBN 978-81-215-1194-0.

- Sheridan, Daniel (1986). The Advaitic Theism of the Bhagavata Purana. Columbia, Mo: South Asia Books. pp. 42–43. ISBN 81-208-0179-2. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Sen, Gunada Charan (1986). Srimadbhagavatam: A Concise Narrative. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 26–28. ISBN 81-215-0036-2.

- Wilson, H.H (1961). The Vishnu Purana. Рипол Классик. p. 108. ISBN 5-87618-744-5.

- Dalal, Roshen (2014). Hindusim--An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin, UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9.

- "The Vishnu Purana: Book IV: Chapter XIX". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Daniélou, Alan (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 183. ISBN 0-89281-354-7.

- Sarmah, Taneswar (1991). Bharadvājas in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 61. ISBN 81-208-0639-5.

- Jan E. M. Houben; Karel Rijk van Kooij (1999). Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History. BRILL. pp. 131–132, 143. ISBN 90-04-11344-4. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Jeaneane D Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-84519-346-1, pages 253–262

- Georg Bühler (1898). "The sacred laws of the Aryas : as taught in the schools of Apastamba, Gautama, Vasishtha and Baudhayana". Internet Archive. The Christian Literature Company. pp. 256–262 (verses II.6.11.1–34). Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Georg Bühler (1898). "The sacred laws of the Aryas : as taught in the schools of Apastamba, Gautama, Vasishtha and Baudhayana". Internet Archive. The Christian Literature Company. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Chaturvedi, S.N. (1985). "The Vaikuṇtha image and the Khajurāho inscription of Yaśovarmmadeva". Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Art. Indian Society of Oriental Art. 14: 49–51.

- T.A.Gopinatha, Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 247–248. ISBN 81-208-0878-9.

- Ānandavardhana; Ingalls, Daniel Henry Holmes (1990). Locana: Volume 49 of The Dhvanyāloka of Ānandavardhana with the Locana of Abhinavagupta. Harvard University Press. p. 694. ISBN 0-674-20278-3.

- Malla, Bansi Lal (1996). Vaiṣṇava Art and Iconography of Kashmir. Abhinav Publications. p. 20. ISBN 81-7017-305-1.

- Misra, Ram Nath (1981). Yaksha cult and iconography. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 6, 22.

- Dikshitar, V.R.Ramachandra (1995). The Purana Index: Volume I (from A to N). Motilal Banarsidass. p. 314.

- "The Mahabharata, Book 1: Adi Parva: Sambhava Parva: Section LXV". Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- von Glasenapp 1999, p. 287.

- Āryaśūra; Justin Meiland (Translator) (2009). Garland of the Buddha's Past Lives. New York University Press. pp. 172, 354. ISBN 978-0-8147-9581-1. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Aiyangar Narayan. Essays On Indo-Aryan Mythology. Asian Educational Services. p. 472. ISBN 978-81-206-0140-6. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- JF Fleet (1906). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- P. 269 Introduction to Buddhist art By Chikyō Yamamoto

- Edkins, Joseph (2013). Chinese Buddhism: A Volume of Sketches, Historical, Descriptive and Critical. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-136-37881-2. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Larson, Gerald James; Potter, Karl H.; Bhattacharya, Ram Shankar (1987). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Sāṃkhya, Volume 4 of The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies. Princeton University Press, (Reprint: Motilal Banarsidass). p. 108. ISBN 978-0-691-60441-1.

Sources

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1376-6

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press

- Witzel, Michael (1995), "Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state" (PDF), EJVS, 1 (4), archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012

External links

- The Sánkhya Aphorisms of Kapila, 1885 translation by James R. Ballantyne, edited by Fitzedward Hall.