Siege of Busanjin

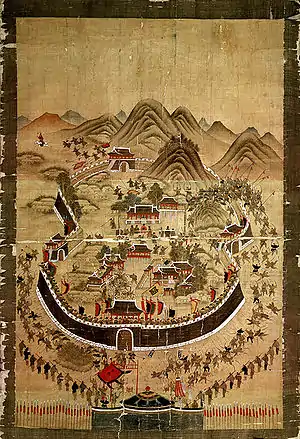

The Siege of Busanjin was a battle fought at Busan between Japanese and Korean forces on April 14, 1592 (Gregorian: May 24, 1592). The attacks on Busan and the neighboring fort of Dadaejin were the first battles of the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98).[6]

| The Siege of Busan Castle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Imjin War | |||||||

The Siege of Busan Castle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Kingdom of Joseon | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 16,700[1] |

600 Soldiers[2] 8,000 Civilians.[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| about 140 casualties |

3,000-8,000 defenders and civilians i.e. Nearly all defenders and civilians 200 captured[4] (Japanese records) | ||||||

Background

The Japanese invasion force consisting of 400 transports bearing 18,700 men under the command of Konishi Yukinaga departed from Tsushima Island on April 13 (Gregorian: May 23) and arrived at Busan harbor without any incident. The commander of Busan, Yeong Bal, spotted the invasion fleet while hunting on Yeong Island off Busan Harbor and rushed back to Busan to prepare defenses.[7] A single vessel bearing the daimyō of Tsushima, Sō Yoshitoshi (who had been a member of the Japanese mission to Korea in 1589), detached from the Japanese fleet with a letter to the commander of Busan, Jeong Bal, demanding that the Korean forces stand down to allow the Japanese armies to proceed on towards China. The letter went unanswered, and the Japanese commenced landing operations from 0400 the following morning. [8]

The Joseon fleet of 150 ships did nothing and sat idle at port while Gyeongsang Left Navy Commander Bak Hong reported to Gyeongsang Right Navy Commander Won Gyun, who thought the invasion might have been a really large trade mission.[9]

The commanders of the Japanese forces were Konishi, Sō, Matsura Shigenobu, Arima Harunobu, Ōmura Yoshiaki, and Gotō Mototsugu, all of whom (with the exception of Matsura) were Kirishitans, as were many of their men .[10] A portion of this force led by Konishi attacked a nearby fort called Dadaejin, while Sō led the main contingent against Busan. [7]

Battle

To establish a beachhead and control Busan shores, a strategy was planned based on the local knowledge of So Yoshitoshi, lord of Tsushima. The plan consisted of dividing their forces and leading simultaneous attacks against the fort, and subsidiary harbor forts of Tadaejin and Seopyeongpo.

Early in the morning of April 14, 1592 (Gregorian: May 24, 1592), Sō Yoshitoshi once again called up Joeng Bal to stand down, assuring that he and his men would be safe if they would stand aside and allow the Japanese to pass. Jeong refused, stating that he was dutifully bound to oppose the Japanese advance unless he received orders from Seoul to do otherwise, and the Japanese attack then commenced.[9] While So Yoshitoshi attacked within the main city walls of Busan, Konishi Yukinaga led the assault on the harbor fort of Tadaejin.

The Japanese tried to take the south gate of Busan Castle first but took heavy casualties and were forced to switch to the north gate. The Japanese took high ground positions on the mountain behind Busan and shot at Korean defenders within the city with their arquebuss until they created a breach in their northern defenses.[5]

The Japanese overwhelmed the Korean defenses by scaling the walls under cover of the arquebuses. This new technology destroyed the Koreans on the walls. Again and again the Japanese would win battles with arquebuses (Korea would not begin to train with these firearms until the Korean General Kim Si-min forged them at a Korean armory).

The Koreans retreated to the second line of defense after the surprise attack of So Yoshitoshi. General Jeong Bal (Hangul: 정발, Hanja :鄭撥) regrouped the Korean archers and counterattacked. By now, the Koreans had retreated to the third line of defence. After hours of fighting, the Koreans ran out of arrows. The Japanese were taking losses and regrouped to attack again.

General Jeong Bal was shot and killed. Morale fell amongst the Korean soldiers and the fort was overrun at around 9:00 in the morning—nearly all of Busan's fighting force was killed.[6] The Japanese massacred the remaining garrison and non-combatants. Not even animals were spared. Yoshitoshi ordered his soldiers to loot and burn valuable items.

The Japanese army now occupied Busan. For the next several years Busan would be a supply depot for the Japanese. The Japanese continued to supply troops and food across the sea to Busan until Korean Admiral Yi Sun-sin attacked Busan with his navy.

Aftermath

Once within the walls of the fortification, the Japanese massacred thousands. "Both men, women, and even dogs and cats were beheaded."[4] Per Korean sources, 3,000-8,000 defenders were killed. According to Japanese records, 8,500 Koreans were killed in Busan and 200 were taken prisoner. [9]

Gyeongsang Left Navy Commander Bak Hong watched the fall of Busan from a distance. He then scuttled his fleet of 100 ships, which included more than 50 warships armed with cannon, and destroyed his weapons and provisions, so that they would not fall into Japanese hands. Abandoning his men, he fled to Hanseong where he would deliver news of the Japanese invasion to the court.[4]

With the fall of Fort Busan, the First Division of the Japanese Army completed its first objective. However, a few miles to the north of Busan lay the fortress of Dongnae; its garrison was a threat to the newly established beachhead. The following day, Konishi Yukinaga and So Yoshitoshi recombined their forces, and then advanced towards the fortress of Dongnae located ten kilometers northeast on the main road to Seoul.[11]

These series of lightning-like attacks marked the beginning of the Seven Year War.

Legacy

With the port in Japanese hands, the area became the primary landing ground for subsequent Japanese deployments to Korea during the Japanese invasion, notably the large army led by Kato Kiyomasa and the slightly smaller army led by Kuroda Nagamasa. It was also the primary Japanese supply base throughout the conflict.

To commemorate the battle, there is a statue of Jeong Bal next to the Japanese Consulate in Busan.[7]

See also

- Castles in Korea

Citations

- Luís Fróis《historia de japam》

- 조선왕조실록 (Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty) 명종실록 (Annals of King Myeongjong) 12권(volume 12), 명종 6년 10월 24일 무인 1번째기사| A record of the size and number of troops in the Busanjin garrison.

- Luís Fróis《historia de japam》

- Hawley 2005, p. 145.

- Swope 2009, p. 89.

- Turnbull 2008, p. 23-24.

- Turnbull 2008, p. 23.

- Hawlely 2005, p. 235-245.

- Hawlely 2005, p. 142.

- Hawlely 2005, p. 241.

- Turnbull 2008, p. 24.

Bibliography

- Alagappa, Muthiah (2003), Asian Security Order: Instrumental and Normative Features, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-4629-8

- Arano, Yasunori (2005), The Formation of a Japanocentric World Order, International Journal of Asian Studies

- Brown, Delmer M. (May 1948), "The Impact of Firearms on Japanese Warfare, 1543–1598", The Far Eastern Quarterly, 7 (3): 236–53

- Eikenberry, Karl W. (1988), "The Imjin War", Military Review, 68 (2): 74–82

- Ha, Tae-hung; Sohn, Pow-key (1977), 'Nanjung Ilgi: War Diary of Admiral Yi Sun-sin, Yonsei University Press, ISBN 978-89-7141-018-9

- Haboush, JaHyun Kim (2016), The Great East Asian War and the Birth of the Korean Nation

- Hawley, Samuel (2005), The Imjin War, The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch/UC Berkeley Press, ISBN 978-89-954424-2-5

- Jang, Pyun-soon (1998), Noon-eu-ro Bo-nen Han-gook-yauk-sa 5: Gor-yeo Si-dae (눈으로 보는 한국역사 5: 고려시대), Park Doo-ui, Bae Keum-ram, Yi Sang-mi, Kim Ho-hyun, Kim Pyung-sook, et al., Joog-ang Gyo-yook-yaun-goo-won. 1998-10-30. Seoul, Korea.

- Kim, Ki-chung (Fall 1999), "Resistance, Abduction, and Survival: The Documentary Literature of the Imjin War (1592–8)", Korean Culture, 20 (3): 20–29

- Kim, Yung-sik (1998), "Problems and Possibilities in the Study of the History of Korean Science", Osiris, 2nd Series, 13: 48–79, JSTOR 301878

- 桑田忠親 [Kuwata, Tadachika], ed., 舊參謀本部編纂, [Kyu Sanbo Honbu], 朝鮮の役 [Chousen no Eki] (日本の戰史 [Nihon no Senshi] Vol. 5), 1965.

- Neves, Jaime Ramalhete (1994), "The Portuguese in the Im-Jim War?", Review of Culture, 18: 20–24

- Niderost, Eric (June 2001), "Turtleboat Destiny: The Imjin War and Yi Sun Shin", Military Heritage, 2 (6): 50–59, 89

- Niderost, Eric (January 2002), "The Miracle at Myongnyang, 1597", Osprey Military Journal, 4 (1): 44–50

- Park, Yune-hee (1973), Admiral Yi Sun-shin and His Turtleboat Armada: A Comprehensive Account of the Resistance of Korea to the 16th Century Japanese Invasion, Shinsaeng Press

- Rockstein, Edward D. (1993), Strategic And Operational Aspects of Japan's Invasions of Korea 1592–1598 1993-6-18, Naval War College

- Sadler, A. L. (June 1937), "The Naval Campaign in the Korean War of Hideyoshi (1592–1598)", Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Second Series, 14: 179–208

- Sansom, George (1961), A History of Japan 1334–1615, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-0525-7

- Sohn, Pow-key (April–June 1959), "Early Korean Painting", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 79 (2): 96–103, JSTOR 595851

- Stramigioli, Giuliana (December 1954), "Hideyoshi's Expansionist Policy on the Asiatic Mainland", Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Third Series, 3: 74–116

- Strauss, Barry (Summer 2005), "Korea's Legendary Admiral", MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, 17 (4): 52–61

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2006), "Beyond Turtleboats: Siege Accounts from Hideyoshi's Second Invasion of Korea, 1597–1598", Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies, 6 (2): 177–206

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2005), "Crouching Tigers, Secret Weapons: Military Technology Employed During the Sino-Japanese-Korean War, 1592–1598", The Journal of Military History, 69: 11–42

- Swope, Kenneth M. (December 2002), "Deceit, Disguise, and Dependence: China, Japan, and the Future of the Tributary System, 1592–1596", The International History Review, 24 (4): 757–1008

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2009), A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598, University of Oklahoma Press

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002), Samurai Invasion: Japan's Korean War 1592–98, Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-0-304-35948-6

- Turnbull, Stephen (2008), The Samurai Invasion of Korea 1592-98, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Turnbull, Stephen (1998), The Samurai Sourcebook, Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-1-85409-523-7

- Villiers, John (1980), SILK and Silver: Macau, Manila and Trade in the China Seas in the Sixteenth Century (A lecture delivered to the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society at the Hong Kong Club. 10 June 1980). The HKUL Digital Initiatives External link in

|title=(help) - Yi, Min-woong (2004), Imjin Wae-ran Haejeonsa: The Naval Battles of the Imjin War [임진왜란 해전사], Chongoram Media [청어람미디어], ISBN 978-89-89722-49-6