Siege of Kiev (1240)

The Siege of Kiev by the Mongols took place between November 28 and December 6, 1240, and resulted in a Mongol victory. It was a heavy morale and military blow to Halych-Volhynia and allowed Batu Khan to proceed westward into Europe.[1]

| Siege of Kiev | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus' | |||||||

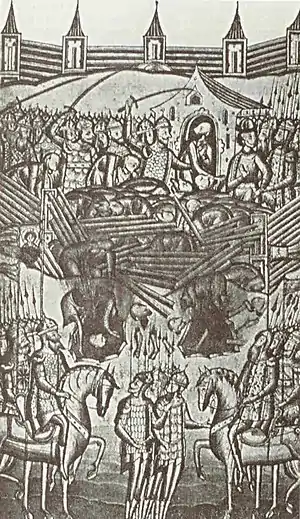

Sack of Kiev in 1240 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Batu Khan | '''Voivode Dmitr''' | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown; probably large | ~1000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown; not very heavy | ~48,000 (including noncombatants) killed | ||||||

Background

Batu Khan and the Mongols began their invasion in late 1237 by conquering the Principality of Ryazan in north-east Rus.[2][3] Then, in 1238 the Mongols went south-west and destroyed the cities of Vladimir and Kozelsk. In 1239, they captured both Pereyaslav and Chernihiv with their sights set on the city of Kiev (Kyiv).[4][3]

When the Mongols sent several envoys to Kiev to demand submission, they were executed by Michael of Chernigov and later Dmytro.[5][6]

The next year, Batu Khan's army under the tactical command of the great Mongol general Subutai reached Kiev. At the time, the city was ruled by the principality of Halych-Volhynia. The chief commander in Kiev was Voivode Dmytro, while Danylo of Halych was in Hungary at that time, seeking a military union to prevent invasion.

Siege

The vanguard army under Batu's cousin Möngke came near the city. Möngke was apparently taken by the splendor of Kiev and offered the city terms for surrender, but his envoys were killed.[7] The Mongols chose to assault the city. Batu Khan destroyed the forces of the Rus vassals, the Chorni Klobuky,[8] who were on their way to relieve Kiev, and the entire Mongol army camped outside the city gates, joining Möngke's troops.

On November 28 the Mongols set up catapults near one of the three gates of old Kiev where tree cover extended almost to the city walls.[9] The Mongols then began a bombardment that lasted several days. On December 6, Kiev's walls were breached, and hand-to-hand combat followed in the streets. The Kievans suffered heavy losses and Dmytro was wounded by an arrow.[4]

When night fell the Mongols held their positions while the Kievans retreated to the central parts of the city. Many people crowded into the Church of the Tithes. The next day, as the Mongols commenced the final assault, the church's balcony collapsed under the weight of the people standing on it, crushing many. After the Mongols won the battle, they plundered Kiev. Most of the population was massacred. [4] Out of 50,000 inhabitants before the invasion, about 2,000 survived.[10] Most of the city was burned and only six out of forty major buildings remained standing. Dmytro, however, was shown mercy for his bravery.[4]

After their victory at Kiev, the Mongols were free to advance into Hungary and Poland.[3]

See also

References

- Janet Martin Medieval Russia, 980–1584, p.139

- Dowling, Timothy (2015). Russia at War: from the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 537.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 1190–1400. Oxford, Great Britain: Osprey Publishing. pp. 45–49.

- Perfecky, George (1973). The Hypatian Codex. Munich, Germany: Wilhelm Fink Publishing House. pp. 43–49.

- The Mongols by Stephen Turnbull, p.81

- Roux, Jean-Paul (2003). Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. "Abrams Discoveries" series. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 131.

- Charles Halperin – The Tatar Yoke, p.43

- V. Minorksy – The Alān Capital *Magas and the Mongol Campaigns, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 14,No. 2 (1952), pp. 221–238

- Alexander V. Maiorov (2016). "The Mongolian Capture of Kiev: The Two Dates". The Slavonic and East European Review. 94 (4): 702. doi:10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.94.4.0702. ISSN 0037-6795.

- Davison, Derek. "Today in European history: the Mongols sack Kyiv (1240)". fx.substack.com. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

External links

- (in Ukrainian) Rutheian chronicle (years 1224–1244), based on Hypatian Codex. (interpreted by Leonid Makhnovets)