Simon de Colines

Simon de Colines (c. 1480 – 1546) was a Parisian printer and one of the first printers of the French Renaissance. He was active in Paris as a printer and worked exclusively for the University of Paris from 1520 to 1546.[1] In addition to his work as a printer; Colines worked as an editor, publisher, and punchcutter.[2]:62 Over the course of his lifetime, he published over 700 separate editions (almost 4% of books published in 16th-century Paris).[2]:64 Colines used elegant roman and italic types and a Greek type, with accents, that were superior to their predecessors. These are now called French old-style, a style that remained popular for over 200 years and revived in the early 20th century.[2]:53 He used rabbits, satyrs, and philosophers as his pressmark.

.jpg.webp)

Life

Colines was born between 1480 and 1490, possibly south of Paris, where his siblings later owned farms.[2]:12 He probably studied at the University of Paris and probably worked for the elder Henri Estienne, and replaced Estienne as press director after his death in 1520. Colines married Estienne's widow, Guyonne Viart, and inherited charge of the press and her six children.[2]:13 He continued working in Estienne's shop until Robert Estienne (Estienne's son) entered the business in 1526, by which time Colines had set up his own shop nearby at Soleil d'or and helped Robert become established as a printer without ties to the university.[1] One scholar, Jeanne Veyrin-Forrer, believes Colines may have furnished French old-style typefaces to his step-son, Robert Estienne.[2]:57 For the next 13 years Colines would cut most of his common print types: romans, italics, and his two best Greeks.[2]:15 In 1528 he began to use italic type. Colines was recognized for using rabbits near a tree as part of his pressmark, but after moving to Soleil d'or he started using satyrs and philosophers as his pressmarks.[2]:17–19[3] In 1539, Colines left Soleil d'or and moved his presses outside Paris's wall, at the sign of the four evangelists,[3] where he stayed until his death in spring in 1546. Colines let his stepson-in-law, Chaudière, take over his location at Soleil d'or and would send him projects either because Colines was ill or overloaded. Upon Colines's death it was Chaudière and not Robert who took over Colines' backlist.[2]:15

Work

.jpg.webp)

Colines may not have been a major contributor of technical innovations relating to typography, but he certainly was an intellectual pioneer in his field. Many of the important written structural elements that we expect to find in books are components that he contributed: title page organization, chapter headings, page numbers, table of contents, bibliographies, etc. In his work for the University of Paris, Colines printed classics by Cicero, Virgil, Euclid, and others.[2]:11, 52 Although he was not a scholar himself, he extended the range of the Estienne firm's learned and scientific works to include the natural sciences, cosmology, and astrology. He is credited with the design of Italic and Greek fonts and of a Roman face for St. Augustine's Sylvius (1531), from which the Garamond types were derived.[2]:65 Compared to Henri Estienne's Romans, Colines spaced the letters more generally and altered some letters to be thinner.[2]:65 In 1529–1531 and in 1536, Louis Blaubloom, also known as Cyanaeus, helped Colines print more editions of the many books Colines was printing. In 1537, Colines started to collaborate with his step-son François Estienne in writing and printing schoolbooks. Starting in 1539, Colines was appointed as one of three officials who had to inspect paper before it was sold.[3] Scholar Veyrin-Forrer estimates that during Colines's busiest times he had three presses and about 15 workers press workers and 10 foundry workers. [3]:lxx

Textbooks

Colines's editions of science books were illustrated with large woodcuts and included editions of Silíceo edited by Rhaetus, Sarzosa, and Fernel. He published versions of Galen's medical texts translated into French. In 1528 Colines started using italics purposefully in his texts, starting with Saint Augustin, and also started using a Greek typeface, starting with Cicero's De senuctute translated into Greek by Theodorus Gaza. When Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples became a tutor for the royal family, he commissioned Colines to print three Latin primers, which included accent marks to indicate long and short vowels, printed in black and red.[3] In 1528, Colines printed De literis syllabis et metris by Terentianus Maurus, with commentary by Nicolas Brissé. For this book, Colines used a roman Gros Romain font which appears to be modeled after one of Aldus Manutius's types from Venice. This was part of a greater trend of changing typography styles in France. Also around this time, a new italic typeface derived from the Gros Romain appears in Colines's 1532 printing of Paul of Aegina's Opus de re medica.[3] The typeface "lacks the curves that terminated the ascenders of the earlier face, while conserving the graceful shape of the ligature et."[3]:lvii

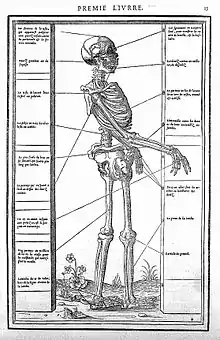

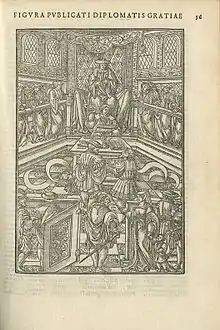

In 1536, Colines printed his most famous edition: Jean Ruel's De natura stirpium, which incorporated a unique garden woodcut on its title page. The same year, Colines printed Demonstrationes by Oronce Finé, which contained a border design reserved for Fine's works.[3] Colines printed Praxis criminis persequendi by Jean Milles de Souvigny in 1541. Colines published De dissectione partium corporis humani libri tres, an anatomy textbook 10 years in the making, in 1545. Charles Estienne wrote the text and his friend Etienne de la Riviėre, a barber-surgeon, illustrated much of it. The woodcuts were based on illustrations and drawings by Berengario, Perino del Vaga, and Mannerist models from the Fontainebleau School. The work was published in Latin and French, and was popular enough to be pirated in Germany. The French version of the anatomy textbook was Colines's last publication.[3]

Religious books and Parliament

In addition to textbooks, Colines also published a few editions of scriptures and some devotional books. In 1522, Colines printed the four Gospels with commentary by Lefèvre d'Étaples called Commentarii initiatorii in quatuor Evangelia. The book was not submitted to the Parisian Faculty of Theology for approval as had been decreed the previous November, and the theologians fined Colines on 9 June 1523, and threatened to seize the remaining copies.[3]:xlix Colines argued that the printing had started in Meaux before the decree, and the theologians consented to let him keep his remaining copies as long as he did not sell them. In 1545, after Lefèvre's death, Parliament censored Commentarii. In 1524, Colines printed Lefèvre's French translations of both the New Testament and the Psalms; however, Colines also published anti-Lutheran pamphlets (Antilutherus), much to Robert Estienne's and Lefèvre's disapproval. Colines was careful to petition for approval from Parliament. In 1526, the theologians prohibited the sale and possession of French language scriptures.[3]

In 1525 and 1527 Colines published Books of Hours with decorations by Geoffroy Tory. Both books together are called the Tory Books of Hours.[2]:156; 70 Colines also published Books of Hours in the 1540s.[2]:167 Colines's miniature Vulgate was widely circulated and went through 50 editions.[2]:52 In 1541 Colines revised a Latin Bible folio with diacritical marks which contained a geographical index by Robert Estienne in Aramaic, Greek, and Latin. The volume, over 800 pages long, was a difficult printing job and published by Galliot du Pré and Lyonese Antoine Vincent.[3]

Colines published a few more anti-Lutheran books in 1526. Colines printed several works by Josse van Clichtove, including Clichtove's refutation to Johannes Oecolampadius (1527) and Clichtove's commentary (1529) on the decrees of the Councils of Sens in 1528. Colines also printed a book of polemical essays by Johann Eck in 1526.[3]

Colines published many books by Erasmus, often for schools. After Erasmus's Colloquia was censured, two secretly printed editions (1528 and 1532) bore Colines's typeface called Mignonne. When Colines printed a New Testament with commentary by Erasmus in a single volume (Testamentum Nouum per Des. Erasmum recognitum) in 1533, he used a typeface even smaller than the Mignonne. In 1542, French Parliament decreed that all books entering Paris should be examined, in order to make sure they contained no "Lutheran errors". The decree also stipulated that all books should contain the name and address of their printer. In 1544, Parliament published a list of censored books, and anyone still owning the books after three days could be incarcerated. The list included four books Colines had published. Colines published few new works after this decree.[3]

Reception

Colines's types were renowned among and often praised by authors and poets of the period including Hubert Sussaneau, Salmon Macrinus, Nicolas Bourbon, and Jean Visagier.[2]:59

Bibliography

- Simon de Colines: An Annotated Catalogue of 230 Examples of his Press, 1520–1546. Salt Lake City: Brigham Young Univ Library, 1995. With an introduction by Jeanne Veyrin-Forrer. (based on the unique collection of the university Brigham Young University and collected by Fred Schreiber who represents 230 editions published by Simon de Colines). Books represented in this catalogue represent nearly a third of the production of Colines during the quarter of century of its career.

References

- Amert, Kay (2005). "Intertwining Strengths: Simon de Colines and Robert Estienne". Book History. 8: 1–10.

- Amert, Kay (2012). The Scythe and the Rabbit: Simon de Colines and the Culture of the Book of Renaissance Paris. Rochester, New York: Cary Graphic Arts Press. ISBN 978-1-933360-56-0.

- Veyrin-Forrer, Jeanne (1995). "Introduction". In schreiber, Fred (ed.). Simon de Colines: An annotated catalog of 230 examples of his press, 1520–1546. Provo, Utah: Friends of the Brigham Young University Library. pp. xlv–lxxxiv.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Simon de Colines. |

- Typographic Exemplars

- Title page by Oronce Fine, from the print shop of Simon de Colines

- Kay Amert research notes on Simon de Colines and his typography, MSS 6804 Series 1 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University

- Simon de Colines, UA 5572 Series 2 at the L. Tom Perry Special Collections Library, Brigham Young University

- Books printed by Simon de Colines at the L. Tom Perry Special Collections Library, Brigham Young University