Sino-Pakistan Agreement

The Sino-Pakistan Agreement (also known as the Sino-Pakistan Frontier Agreement and Sino-Pak Boundary Agreement) is a 1963 document between the governments of Pakistan and China establishing the border between those countries.[1]

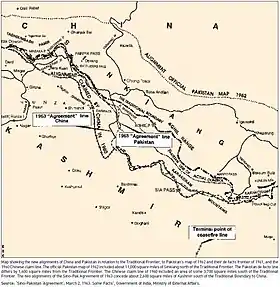

It resulted in China ceding over 1,942 square kilometres (750 sq mi) to Pakistan and Pakistan recognizing Chinese sovereignty over hundreds of square kilometers of land in Northern Kashmir and Ladakh.[2][3] The agreement is not recognized as legal by India, which also claims sovereignty over part of the land. In addition to increasing tensions with India, the agreement shifted the balance of the Cold War by bringing Pakistan and China closer together while loosening ties between Pakistan and the United States.

Issue and result

In 1959, Pakistan became concerned that Chinese maps showed areas of Pakistan in China. In 1961, Ayub Khan sent a formal Note to China, there was no reply.

After Pakistan voted to grant China a seat in the United Nations, the Chinese withdrew the disputed maps in January 1962, agreeing to enter border talks in March. The willingness of the Chinese to enter the agreement was welcomed by the people of Pakistan. Negotiations between the nations officially began on October 13, 1962 and resulted in an agreement being signed on 2 March 1963.[1] It was signed by foreign ministers Chen Yi for the Chinese and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto for the Pakistani.

The agreement resulted in China and Pakistan each withdrawing from about 1,900 square kilometres (750 square miles) of territory, and a boundary on the basis of the 1899 British Note to China as modified by Lord Curzon in 1905. Indian writers have insisted that in this transaction, Pakistan surrendered 5,300 km2 (2,050 sq mi) of territory to China (to which they believe it had no right in the first place). In fact, if anything, Pakistan gained a bit of territory, around 52 km2 (20 sq mi), south of the Khunjerab Pass. The claim given up by Pakistan was the area north of the Uprang Jilga River which also included the Raksam Plots where the Mir of Hunza had enjoyed taxing and grazing rights throughout much of the late 19th Century as part of agreements with Chinese authorities in Sinkiang. Despite this, sovereignty over area was never challenged by the Mir of Hunza, the British or the State of Jammu and Kashmir. [4]

Significance

The agreement was moderately economically advantageous to Pakistan, which received grazing lands in the deal, but of far more significance politically, as it both diminished potential for conflict between China and Pakistan and, Syed indicates, "placed China formally and firmly on record as maintaining that Kashmir did not, as yet, belong to India.[5] Time, reporting on the matter in 1963, expressed the opinion that by signing the agreement Pakistan had further "dimmed hopes of settlement" of the Kashmir conflict between Pakistan and India. Under this Sino-Pakistan Agreement, Pakistani control to a part of northern Kashmir was recognized by China.[1]

During this period, China was in dispute with India regarding Kashmir's eastern boundary, with India making claims of the border having been demarcated beforehand and China making claims that such demarcations had never happened. Pakistan and China recognized in their agreement that the border had been neither delimited nor demarcated, providing support to the Chinese position.[6]

For Pakistan, which had border disputes on its eastern and western borders, the agreement provided relief by securing its northern border from any future contest. The Treaty also provided for clear a demarcation of the boundary for Pakistan, which would continue to serve as the boundary even after Kashmir dispute might be resolved.[6]

According to Jane's International Defence Review, the agreement was also of significance in the Cold War, as Pakistan had ties with the United States and membership in the Central Treaty Organization and the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization.[7] The agreement was part of an overall tightening of association with China for Pakistan, which resulted in Pakistan's distancing from the United States.[7][8][9] After defining borders, the two countries also entered into agreements with respect to trade and air-travel, the latter of which was the first such international agreement China had entered with a country that was not Communist.[10]

Relation to the claim by the Republic of China

The Republic of China now based in and commonly known as Taiwan does not recognize any Chinese territorial changes based on any border agreements signed by the People's Republic of China with any other countries, including this one,in accordance to the Constitution of the Republic of China and its Additional Articles. Pakistan does not recognize the ROC as a state. [11]

References

- "Signing with the Red Chinese". Time (magazine). 15 March 1963. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- NOORANI, A.G. (14 January 2012). "Map fetish" (Volume 29 - Issue 01). Frontline. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (1998), State, Nation and Ethnicity in Contemporary South Asia, A&C Black, p. 148, ISBN 978-1-85567-578-0: "As a friendly gesture some territory in the northern areas was surrendered to China and a treaty was signed which stated that there were no border disputes between the two countries."

- Lamb, Alastair (1991). "Kashmir A Disputed Legacy 1846-1990" (2nd Impression). Oxford University Press. pp.40, 51, 70. ISBN 0-19-577424-8.

- "Factbox: India and China border dispute festers". Reuters. 15 November 2006.

- Yousafzai, Usman Khan. 1963 Sino-Pak Treaty: A Legal Study into the Border Delimitation between Pakistan and China. ISBN 979-8675050000.

- "Strategic and security issues: Pakistan-China defense co-operation an enduring relationship". Jane's International Defence Review. 1 February 1993. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Dixit, Jyotindra Nath (2002). India-Pakistan in War & Peace. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 0-415-30472-5.

- Mitra, Subrata Kumar; Mike Enskat; Clemens Spiess (2004). Political parties in South Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 157. ISBN 0-275-96832-4.

- Syed, 93-94.

- "ROC Chronology: Jan 1911 – Dec 2000". Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2009. “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs declares border agreements signed between the Peking regime and Outer Mongolia and Pakistan illegal and not binding on the ROC.“

External links

- The Geographer (15 November 1968), China – Pakistan Boundary (PDF), International Boundary Study, 85, US Office of the Geographer, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2012 – via Florida State University College of Law