Yarkand River

The Yarkand River (or Yarkent River, Yeh-erh-ch'iang Ho) is a river in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of western China. It originates in the Rimo Glacier in a part of the Karakoram range and disputed between India, China and Pakistan, and flows into the Tarim River or Neinejoung River, with which it is sometimes identified. However, in modern times, the Yarkand river drains into the Shangyou Reservoir and exhausts its supply without reaching the Tarim river. The Yarkand River is approximately 1,332.25 km (827.82 mi) in length, with an average discharge of 210 m3/s (7,400 cu ft/s).

| Yarkand River | |

|---|---|

Yarkand River | |

| Location | |

| Country | China & Pakistan |

| Province | Xinjiang & Karakoram or Gilgit-Baltistan |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Rimo Glacier, Karakoram range at an Altitude of 4,290.25 m (14,075.6 ft) |

| • coordinates | 35.547983°N 77.482907°E |

| Mouth | |

• location | Tarim River or Neinejoung River |

• coordinates | 40.459°N 80.866°E |

| Length | 1,332.25 km (827.82 mi) |

| Basin size | 98,900 km2 (38,200 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 210 m3/s (7,400 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Tarim→ Taitema Lake |

| Landmarks | Yarkand |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Shaksgam, Tashkurgan, Kashgar |

| • right | Shigar River, Shimshal River, Khunjerab River |

| Waterbodies | Shangyou Reservoir |

| Yarkand River | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur | يەكەن دەرياسى | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 葉爾羌河 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 叶尔羌河 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

A part of the river valley is known to the Kyrgyz people as Raskam, and the upper course of the river itself is called the Raskam River.[1] Another name of the river is Zarafshan.[2] The area was once claimed by the ruler of Hunza.

Course

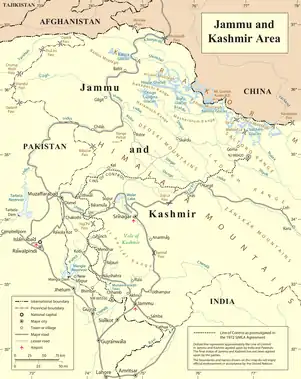

The river originates from the Rimo Glacier in the Karakoram range in India on Sinkiang border region, south of the Kashgar Prefecture.[3] It flows roughly due north until reaching the foot of the Kunlun Mountains. Then it flows northwest where it receives waters from the Shaksgam River, which also originates from the Rimo Glacier. The Shaksgam is also known in its lower course (before falling into the Yarkand) as the Keleqing River (Chinese: 克勒青河; pinyin: Kèlèqīng Hé).

Then Yarkand River flows north, through the Bolor-Tagh mountains parallel to the Tashkurgan valley, eventually receiving the waters of the Tashkurgan River from the west. It is then impounded by the Aratax dam, which was completed in 2019 to store 2.2 km3 (1,800,000 acre⋅ft) for flood control, irrigation and hydropower generation.[4]

After this, the river turns northeast and enters the Tarim Basin, forming a rich oasis that waters the Yarkant county. Continuing northeast, it receives the Kashgar River from the west, eventually draining into the Shangyou Reservoir.

Even though the river originally drained into the Tarim River, development along its course in recent decades has depleted its flow. During the period 1986 to 2000, it flowed into the Tarim River only once.[5]

The drainage area of Yarkand is 108,000 sq. km. It irrigates areas in Taxkorgan, Yecheng, Poskam, Yarkand, Makit and Bachu counties. It also irrigates ten mission fields in the Agricultural Division.[6]

History

The ancient Silk Route into South Asia followed the Yarkand River valley. From Aksu, it went via Maral Bashi (Bachu) on the bank of the Yarkand River, to the city of Yarkand (Shache). From Yarkand, the route crossed the Bolor-Tagh mountains through the river valleys of Yarkand and Tashkurgan to reach the town of Tashkurgan. From there, it crossed the Karakoram mountains through one of the western passes (Kilik, Mintaka or Khunjerab) to reach Gilgit in northern Kashmir. Then it went on to Gandhara (the vicinity of present day Peshawar).[7][8] The Indian merchants from Gandhara introduced the Kharosthi script into the Tarim Basin, and the Buddhist monks followed in their wake, spreading Buddhism.[9] The Chinese Buddhist traveller Fa Xian is believed to have followed this route.

With the Arab conquest of Khurasan in 651 AD, the main Silk route to western Asia was interrupted, and the importance of the South Asian route increased. Gilgit as well as Baltistan find increased mention in the Chinese chronicles (under the names Great Po-lu and Little Po-lu, from the old name Bolor). China invaded Gilgit in 747 AD to secure its routes to Gandhara and prevent Tibetan influence. But the effects of the invasion appear to have been short-lived, as Turkic rule took hold in Gilgit.[10][11]

It is possible that alternative trade routes developed after this time between Yarkand and Ladakh via the Karakash Valley. The region of Hunza adjoining Xinjiang, which contained the passes through the Karakoram range, began to split off from Gilgit as an independent state around 997, and internecine wars with Gilgit as well as neighbouring Nagar became frequent.[12][13] The rising importance of the Ladakh route is illustrated by the raids into Ladakh conducted by Mirza Abu Bakr Dughlat who took control of Kashgaria in 1465. His successor, Sultan Said Khan launched a proper invasion of Ladakh and Kashmir in 1532, led by his general Mirza Haidar Dughlat.[14]

Gallery

_p61_PLATE19._SINKIANG_(14597194848).jpg.webp) Map including Zerafshan R. and Raskem daria (1917)

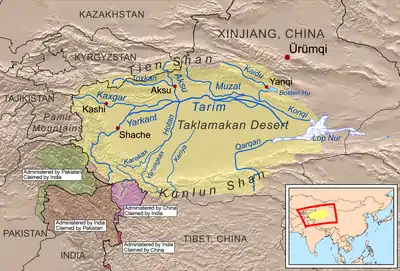

Map including Zerafshan R. and Raskem daria (1917) Rivers of the Tarim Basin

Rivers of the Tarim Basin.png.webp) Moghulistan (Chagatai Khanate), 1490 AD

Moghulistan (Chagatai Khanate), 1490 AD Map including part of the Yarkand River (labeled as YĀRKAND RIVER) (AMS, 1955)

Map including part of the Yarkand River (labeled as YĀRKAND RIVER) (AMS, 1955) Map including the Yarkand River (labeled as Yeh-erh-ch'iang Ho) and surrounding region from the International Map of the World (AMS, 1966)[lower-alpha 1]

Map including the Yarkand River (labeled as Yeh-erh-ch'iang Ho) and surrounding region from the International Map of the World (AMS, 1966)[lower-alpha 1] Map including part of the Yarkand River (Yeh-erh-ch'iang Ho) (ACIC, 1969)

Map including part of the Yarkand River (Yeh-erh-ch'iang Ho) (ACIC, 1969) Map including the upper reaches of the Yarkand River

Map including the upper reaches of the Yarkand River Yarkand River

Yarkand River Sheep on the bank of the Yarkand River

Sheep on the bank of the Yarkand River Ferry on the Yarkand River (1915)

Ferry on the Yarkand River (1915) Langar Bridge (兰干桥) on the Yarkand River

Langar Bridge (兰干桥) on the Yarkand River

Notes

- From map: "DELINEATION OF INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES MUST NOT BE CONSIDERED AUTHORITATIVE"

References

- S.R. Bakshi, Kashmir through Ages ISBN 81-85431-71-X vol 1 p.22, in Google Books

- NGIA GeoNames search

- Ahmad, Naseeruddin; Rais, Sarwar (1998), Himalayan Glaciers, APH Publishing, p. 50, ISBN 978-81-7024-946-7

- "Hydro dam built to tame Yarkant River in Xinjiang". China Daily. 2019-09-06.

- Wilderer, Peter A.; Zhu, J.; Schwarzenbeck, N. (2003), Water in China, IWA Publishing, pp. 5–, ISBN 978-1-84339-501-0

- Chen, Yaning (2014), Water Resources Research in Northwest China, Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 16–, ISBN 978-94-017-8017-9

- Harmatta 1996, pp. 492-493.

- Bagchi, Prabodh Chandra (2011), Bangwei Wang; Tansen Sen (eds.), India and China: Interactions through Buddhism and Diplomacy: A Collection of Essays by Professor Prabodh Chandra Bagchi, Anthem Press, pp. 186–, ISBN 978-0-85728-821-9

- Harmatta 1996, pp. 425-426.

- Litvinsky 1996, pp. 374–375.

- Dani 1998, p. 222.

- Dani 1998, pp. 223, 224.

- Pirumshoev & Dani 2003, pp. 238, 242.

- Khan & Habib 2003, p. 330.

Bibliography

- Harmatta, János (1996), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250 (PDF), UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5

- Litvinsky, B. A. (1996), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750 (PDF), UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1998), "The Western Himalayan States", in M. S. Asimov; C. E. Bosworth (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV, Part 1 — The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century — The historical, social and economic setting (PDF), UNESCO, pp. 215–225, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- Pirumshoev, H. S.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003), "The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States", in Chahryar Adle; Irfan Habib (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. V — Development in contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century (PDF), UNESCO, pp. 225–246, ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1

- Khan, Iqtidar A.; Habib, Irfan (2003), "International Relations", in Chahryar Adle; Irfan Habib (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume V: Development in contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century (PDF), UNESCO Publishing, pp. 327–345, ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1

External links

- Yarkand River plotted on OpenStreetMap.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yarkand River. |