Slovene literature

Slovene literature is the literature written in the Slovene language. It spans across all literary genres with historically the Slovene historical fiction as the most widespread Slovene fiction genre. The Romantic 19th-century epic poetry written by the leading name of the Slovene literary canon, France Prešeren, inspired virtually all subsequent Slovene literature.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Slovenia |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Sport |

|

Literature played an important role in the development and preservation of the Slovene identity because the Slovene nation did not have its own state until 1991 after the Republic of Slovenia emerged from the breakup of Yugoslavia.[1] Poetry, narrative prose, drama, essay, and criticism kept the Slovene language and culture alive, allowing - in the words of Anton Slodnjak - the Slovenes to become a real nation, particularly in the absence of masculine attributes such as political power and authority.[1]

Early literature

There are accounts that cite the existence of an oral literary tradition that preceded the Slovene written literature.[4] This was mostly composed of folk songs and also prose, which included tales of myths, fairy tales, and narrations.[5]

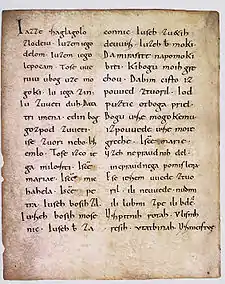

First written text

The earliest documents written in the Old Slovene are the Freising manuscripts (Brižinski spomeniki), dated between 972 and 1022, found in 1803 in Freising, Germany. This book was written for the purpose of spreading Christianity to the Alpine Slavs and contained terms concerned with the institutions of authority such as oblast (authority), gospod (lord), and rota (oath).[6]

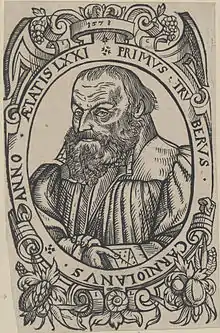

First books

The first books in Slovene were Catechismus and Abecedarium, written by the Protestant reformer Primož Trubar in 1550 and printed in Schwäbisch Hall.[7] Based on the work by Trubar, who from 1555 until 1577 translated into Slovene and published the entire New Testament, Jurij Dalmatin translated the entire Bible into Slovene from c. 1569 until 1578 and published it in 1583. In the second half of the 16th century, Slovene became known to other European languages with the multilingual dictionary, compiled by Hieronymus Megiser. Since then each new generation of Slovene writers has contributed to the growing corpus of texts in Slovene. Particularly, Adam Bohorič's Arcticae horulae, the first Slovene grammar, and Sebastjan Krelj's Postilla Slovenska, became the bases of the development of Slovene literature.[5]

Historical periods

Middle Ages

Folk poetry

Protestant reformation

Counter-reformation

Baroque

Age of Enlightenment

1830–1849

1849–1899

Fin-de-siecle

This period encompasses 1899–1918.

Late realism

1918–1941

1918–1926

1918–1930

1930–1941

1941–1945

1945–1990

Neo-realism

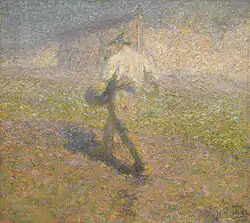

Intimism

Intimism (Slovene: intimizem) was a poetic movement, the main themes of which were love, disappointment and suffering and the projection of poet's inner feelings onto nature.[8] Its beginner is Ivan Minatti, who was followed by Lojze Krakar. The climax of Intimism was achieved in 1953 with a collection of poetry titled Poems of the Four (Pesmi štirih), written by Janez Menart, Ciril Zlobec, Kajetan Kovič and Tone Pavček.[9] An often neglected female counterpart to the four was Ada Škerl, whose subjective and pessimistic poetic sentiment was contrary to the post-war revolutionary demands in the People's Republic of Slovenia.[10]

Modernism

Postmodernism

Post 1990

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slovene-language literature. |

- Daskalova, Krassimira (2008). Aspasia: The International Yearbook of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European Women's and Gender History. New Milford, CT: Berghahn Books. p. 31. ISBN 9781845456344.

- Smrekar, Andrej. "Slovenska moderna" [Slovene Early Modernism] (in Slovenian). National Gallery of Slovenia. Archived from the original on 2013-10-26.

- Naglič, Miha (6 June 2008). "Je človek še Sejalec" [Is a Man Still a Sower]. Gorenjski glas (in Slovenian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2013.

- McKelvie, Robin; McKelvie, Jenny (2008). Slovenia. Guilford, CT: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 38. ISBN 9781841622118.

- Klemencic, Matjaz; Žagar, Mitja (2004). The Former Yugoslavia's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 31. ISBN 1576072940.

- Škrubej, Katja (2002). Ritus gentis Slovanov v vzhodnih Alpah: Model rekonstrukcije pravnih razmerij na podlagi najstarejšega jezikovnega gradiva. Ljubljana: Zalozba ZRC. p. 208.

- Ahačič, Kozma (2013). "Nova odkritja o slovenski protestantiki" [New Discoveries About the Slovene Protestant Literature] (PDF). Slavistična revija (in Slovenian and English). 61 (4): 543–555.

- Pavlič, Darja (May 2008). "Contextualizing contemporary Slovenian lyric poetry within literary history" (DOC). Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Archived copy" (in Slovenian). Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-02-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Umrla Ada Škerl" [Ada Škerl Deceased]. Delo.si (in Slovenian). 1 June 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2011.