Sludge metal

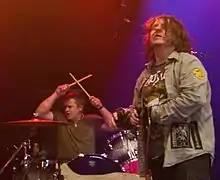

Sludge metal (also known as sludge or sludge doom) is a genre of heavy metal music that originated through combining elements of doom metal and hardcore punk. It is typically harsh and abrasive, often featuring shouted vocals, heavily distorted instruments and sharply contrasting tempos. The Melvins from the US state of Washington produced the first sludge metal albums in the mid-late 1980s.[4][5]

| Sludge metal | |

|---|---|

| Other names | |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Mid-late 1980s Washington State, United States |

| Fusion genres | |

| Sludgecore | |

| Local scenes | |

| |

| Other topics | |

Characteristics

Sludge metal generally combines the slow tempos, heavy rhythms and dark, pessimistic atmosphere of doom metal with the aggression, shouted vocals and occasional fast tempos of hardcore punk.

As The New York Times wrote on The Melvins, "The shorthand term for the kind of rock descending from early Black Sabbath and late Black Flag is sludge, because it's so slow and dense."[6] According to Metal Hammer, sludge metal "[s]pawned from a messy collision of Black Sabbath's downcast metal, Black Flag's tortured hardcore and the sub/dom grind of early Swans, shaken up with lashings of cheap whisky and bad pharmaceuticals".[7] Mike IX Williams, vocalist for Eyehategod, suggests that "the moniker of sludge apparently has to do with the slowness, the dirtiness, the filth and general feel of decadence the tunes convey".[5]

Due to the similarities between sludge and stoner metal, there is often a crossover between the two genres,[8][9] but sludge metal generally avoids stoner metal's usage of psychedelia.

History

In the early 1980s, the Seattle branch of the indie movement was influenced by punk rock, however it removed its speed and its structure and added elements of metal. The Melvins slowed down punk rock to develop their own slow, heavy, sludgy sound.[10] In 1984, the punk rock band Black Flag went visiting small towns across the US to bring punk to the more remote parts of the country. By this time their music had become slow and sludgy, less like the Sex Pistols and more like Black Sabbath. Krist Novoselic (later the bass player with Nirvana) recalls going along with the Melvins to see one of these shows, after which the Melvins front man Buzz Osborne began writing "slow and heavy riffs" to form a dirge–like music that was the beginning of northwest grunge.[11] In the remoteness of Montesano, Washington, the Melvins were able to experiment without fear of rejection but also to reach an audience and interact with other bands.[12] Initially, the Melvins played fast hardcore punk, and when other bands were doing the same they slowed down as much as they could and added heavy metal into their mix.[3]

The Melvins' Six Songs (1986) is regarded as the first sludge album,[5] with Gluey Porch Treatments (1987) regarded as the first post-punk sludge album.[4] The hardcore punk spasms that the Melvins mixed into the dirge-like songs of Gluey Porch Treatments provides one of the key differences that distinguishes sludge from doom metal.[12] At this time, the band was also key in the development of the Washington grunge scene.[5] The Nirvana single record "Love Buzz/Big Cheese" (1988) was described by their record label Sub Pop as "heavy pop sludge".[13] The Seattle music author and journalist Gillian G. Gaar writes that Nirvana's first studio album Bleach (1989) "does have its share – some would say more than its share – of dirty sludge".[14]

The American music author and journalist Michael Azerrad described the short-lived Seattle band Blood Circus (1988) as a sludge metal band,[15] with rock journalist Ned Raggett writing in Allmusic describing the band's music as "rough and ready, sludgy guitar rock with a bad attitude".[16] Examples of crossover tracks between sludge and grunge include Soundgarden's "Slaves & Bulldozers" (1991) and Alice in Chains' "Sludge Factory" (1995).[12]

According to vocalist Phil Anselmo:

Back in those days, everything in the underground was fast, fast, fast. It was the rule of the day...But when the Melvins came out with their first record, Gluey Porch Treatments, it really broke the mold, especially in New Orleans. People began to appreciate playing slower.[17]

Key bands in the development of sludge metal include Acid Bath, Buzzoven, Corrupted, Crowbar, Down, Eyehategod, and Grief in addition to the Melvins.[12] By the late 1990s, small sludge scenes could be found across many countries.[18]

By the early 2000s, sludge metal had formed cross-over works with stoner metal. Examples of cross-over tracks between sludge and stoner metal include Bongzilla – Gateway (2002) and High on Fire – The Yeti (2002).[12]

Sludgecore

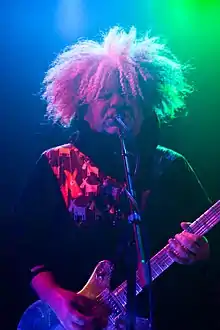

Eyehategod formed in Harvey, Louisiana in 1988 and is credited with originating a new style - New Orleans hardcore-edged sludge.[19] Another point of view is that New Orleans was the birthplace of the sludgecore movement, with Eyehategod being given the most credit for it.[20] Sludgecore combines sludge metal with hardcore punk, and possesses a slow pace,[20][21] a low guitar tuning,[20][21] and a grinding dirge-like feel.[21] Bands regarded as sludgecore include Acid Bath, Eyehategod, and Soilent Green,[22] and all three formed in Louisiana. Crowbar formed in 1991 and mixed "detuned, lethargic sludged-out metal with hardcore and southern elements".[23] According to rock journalist Steve Huey writing in Allmusic, Eyehategod was a sludge metal band that became part of the "Southern sludgecore scene". This scene also included Crowbar and Down, with all three bands being influenced by Black Flag, Black Sabbath, and the Melvins.[24] Some of these bands incorporated Southern rock influences.[25][26][27]

Eyehategod's album "My Name Is God" (1992) includes slow-paced songs similar to early Melvins, but contains a few fast tempo hardcore punk passages.[25] The guitars (electric guitar and bass guitar) are often played with large amounts of feedback.[25][28] Vocals are usually shouted or screamed.[25][28][26] The lyrics of Crowbar are generally pessimistic in nature.[29] Buzzoven lyrics concerning drug abuse,[30] and Acid Bath concerning rape, abortion, death, and self-loathing can be found.[31]

See also

References

- "These Are The 13 Most Essential Sludge Records". Kerrang!. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- Piper, Jonathan (2013). Locating experiential richness in doom metal (PhD). UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations. University of California, San Diego. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- Azerrad, Michael (1993). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-385-47199-8.

- Bukszpan 2012, pp. 192-193

- "Sludge Special". Terrorizer. No. 187. August 2009. pp. 43–56. ISSN 1350-6978.

- "Pop/Jazz Listings, page 2". The New York Times. October 5, 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- Chantler, Chris (October 12, 2016). "The 10 essential sludge metal albums". Metal Hammer. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Serba, John. "Bongzilla - Gateway". AllMusic. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

…sounding like a cross between Sleep's drowsy, Black Sabbathy meanderings and Electric Wizard/Burning Witch-style gut-curdling, muddy sludge.

- Mason, Stewart. "Kylesa". AllMusic. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

…elements of hardcore punk, psychedelic stoner rock, technical speed metal, and good old-fashioned Black Sabbath sludge appear in their music.

- Anderson, Kyle (2007). Accidental Revolution: The Story of Grunge. Macmillan. pp. 12–22. ISBN 978-0-312-35819-8.

- Novoselic, Krist (2004). Of Grunge and Government: Let's Fix This Broken Democracy!. Akashic Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0971920651.

- King, Ian Frederick (2018). "Sludge Metal". Appetite for Definition: An A–Z Guide to Rock Genres. Harper-Collins. pp. 404–405. ISBN 978-0-06-268888-0.

- Azerrad, Michael (2013). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Crown. p. 85. ISBN 9780307833730. Kindle edition

- Gaar, Gillian G. (2009). "The Recordings". The Rough Guide to Nirvana. Rough Guides. p. 141. ISBN 978-1858289458.

- Azerrad, Michael (2013). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Crown. p. 140. ISBN 9780307833730. Kindle edition

- Raggett, Ned. "Blood Circus – "Primal Rock Therapy"". AllMusic. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Mudrian, Albert, ed. (2009). Precious Metal: Decibel Presents the Stories Behind 25 Extreme Metal Masterpieces. Da Capo Press. p. 268. ISBN 9780306818066.

- "Sludge Special - Part 2". Terrorizer. No. 188. September 2009. pp. 40–57. ISSN 1350-6978.

- Sharpe-Young, Garry (2005). New Wave of American Heavy Metal. Zonda. p. 137. ISBN 978-0958268400.

- Bukszpan 2012, pp. 91

- Pearson, David (2020). "Ch3-The Dystopian Sublime of Extreme Hardcore Punk". Rebel Music in the Triumphant Empire: Punk Rock in the 1990s United States. Oxford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0197534885.

- Rosenberg, Axl; Krovatin, Chris (2017). Hellraisers: A Complete Visual History of Heavy Metal Mayhem. Race Point Publishing. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-63106-430-2.

- Sharpe-Young, Garry (2005). New Wave of American Heavy Metal. Zonda. p. 97. ISBN 978-0958268400.

- Huey, Steve. "Eyehategod". AllMusic. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- York, William. "Eyehategod - In the Name of Suffering". AllMusic. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- York, William. "Eyehategod - Take as Needed for Pain". AllMusic. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- York, William. "Soilent Green". AllMusic. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- York, William. "Eyehategod - Dopesick". AllMusic. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Jeffries, Vincent. "Crowbar - Crowbar". AllMusic. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Kennedy, Patrick. "Buzzov-en - To a Frown". AllMusic. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- York, William. "Acid Bath - When the Kite String Pops". AllMusic. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

Publications

- Bukszpan, Daniel (2012). The Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal. Sterling, New York. ISBN 978-1402792304.