Spider taxonomy

Spider taxonomy is that part of taxonomy that is concerned with the science of naming, defining and classifying all spiders, members of the Araneae order of the arthropod class Arachnida with about 46,000 described species. However, there are likely many species that have escaped the human eye to this day, and many specimens stored in collections waiting to be described and classified. It is estimated that only one third to one half of the total number of existing species have been described.[1]

Arachnologists currently divide spiders into two suborders with about 114 families.

Due to constant research, with new species being discovered every month and others being recognized as synonyms, the number of species in the families is bound to change and can never reflect the present status with total accuracy. Nevertheless, the species numbers given here are useful as a guideline – see the table of families at the end of the article.

History

Spider taxonomy can be traced to the work of Swedish naturalist Carl Alexander Clerck, who in 1757 published the first binomial scientific names of some 67 spiders species in his Svenska Spindlar ("Swedish Spiders"), one year before Linnaeus named over 30 spiders in his Systema Naturae. In the ensuing 250 years, thousands more species have been described by researchers around the world, yet only a dozen taxonomists are responsible for more than a third of all species described. The most prolific authors include Eugène Simon of France, Norman Platnick and Herbert Walter Levi of the United States, Embrik Strand of Norway, and Tamerlan Thorell of Sweden, each having described well over 1,000 species.[2]

Overview of phylogeny

At the very top level, there is broad agreement on the phylogeny and hence classification of spiders, which is summarized in the cladogram below. The three main clades into which spiders are divided are shown in bold; as of 2015, they are usually treated as one suborder, Mesothelae, and two infraorders, Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae, grouped into the suborder Opisthothelae.[3][4] The Mesothelae, with about 140 species in 8 genera as of October 2020, make up a very small proportion of the total of around 49,000 known species. Mygalomorphae species comprise around 7% of the total, the remaining 93% being in the Araneomorphae.[note 1]

| Araneae (spiders) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Araneomorphae are divided into two main groups: the Haplogynae and the Entelegynae. The Haplogynae make up about 10% of the total number of spider species, the Entelegynae about 83%.[note 1] The phylogenetic relationships of the Haplogynae, Entelegynae and the two smaller groups Hypochiloidea and Austrochiloidea remain uncertain as of 2015. Some analyses place both Hypochiloidea and Austrochiloidea outside Haplogynae;[5] others place the Austrochiloidea between the Haplogynae and the Entelegynae;[6][7] the Hypochiloidea have also been grouped with the Haplogynae.[8] Earlier analyses regarded the Hypochiloidea as the sole representatives of a group called the Paleocribellatae, with all other araneomorphs placed in the Neocribellatae.[9]

The Haplogynae are a group of araneomorph spiders with simpler male and female reproductive anatomy than the Entelegynae. Like the mesotheles and mygalomorphs, females have only a single genital opening (gonopore), used both for copulation and egg-laying;[10] males have less complex palpal bulbs than those of the Entelegynae.[11] Although some studies based on both morphology and DNA suggest that the Haplogynae form a monophyletic group (i.e. they comprise all the descendants of a common ancestor),[12][8] this hypothesis has been described as "weakly supported", with most of the distinguishing features of the group being inherited from ancestors shared with other groups of spiders, rather than being clearly indicative of a separate common origin (i.e. being synapomorphies).[13] One phylogenetic hypothesis based on molecular data shows the Haplogynae as a paraphyletic group leading to the Austrochilidae and Entelegynae.[14]

The Entelegynae have a more complex reproductive anatomy: females have two "copulatory pores" in addition to the single genital pore of other groups of spiders; males have complex palpal bulbs, matching the female genital structures (epigynes).[12] The monophyly of the group is well supported in both morphological and molecular studies. The internal phylogeny of the Entelegynae has been the subject of much research. Two groups within this clade contain the only spiders that make vertical orb webs: the Deinopoidea are cribellate – the adhesive properties of their webs are created by packets of thousands of extremely fine loops of dry silk; the Araneoidea are ecribellate – the adhesive properties of their webs are created by fine droplets of "glue". In spite of these differences, the webs of the two groups are similar in their overall geometry.[15] The evolutionary history of the Entelegynae is thus intimately connected with the evolutionary history of orb webs. One hypothesis is that there is a single clade, Orbiculariae, uniting the orb web makers, in whose ancestors orb webs evolved. A review in 2014 concluded that there is strong evidence that orb webs evolved only once, although only weak support for the monophyly of the Orbiculariae.[16] One possible phylogeny is shown below; the type of web made is shown for each terminal node in order of the frequency of occurrence.[17]

| Entelegynae |

| ||||||||||||||||||

If this is correct, the earliest members of the Entelegynae made webs defined by the substrate on which they were placed (e.g. the ground) rather than suspended orb webs. True orb webs evolved once, in the ancestors of the Orbiculariae, but were then modified or lost in some descendants.

An alternative hypothesis, supported by some molecular phylogenetic studies, is that the Orbiculariae are paraphyletic, with the phylogeny of the Entelegynae being as shown below.[18]

| Entelegynae |

| ||||||||||||

On this view, orb webs evolved earlier, being present in the early members of the Entelegynae, and were then lost in more groups,[19] making web evolution more convoluted, with different kinds of web having evolved separately more than once.[16] Future advances in technology, including whole-genome sampling, should lead to "a clearer image of the evolutionary chronicle and the underlying diversity patterns that have resulted in one of the most extraordinary radiations of animals".[16]

Suborder Mesothelae

Mesothelae resemble the Solifugae ("wind scorpions" or "sun scorpions") in having segmented plates on their abdomens that create the appearance of the segmented abdomens of these other arachnids. They are both few in number and also limited in geographical range.

- †Arthrolycosidae (primitive spiders, extinct)

- †Arthromygalidae (primitive spiders, extinct)

- Liphistiidae (primitive burrowing spiders)

Suborder Opisthothelae

Suborder Opisthothelae contains the spiders that have no plates on their abdomens. It can be somewhat difficult on casual inspection to determine whether the chelicerae of members are of the sort that would classify them as mygalomorphs or araneomorphs. The spiders that are called "tarantulas" in English are so large and hairy that inspection of their chelicerae is hardly necessary to categorize one of them as a mygalomorph. Other, smaller, members of this suborder, however, look little different from the araneomorphs. (See the picture of Sphodros rufipes below.) Many araneomorphs are immediately identifiable as such since they are found on webs designed for the capture of prey or exhibit other habitat choices that eliminate the possibility that they could be mygalomorphs.

Infraorder Mygalomorphae

Spiders in infraorder Mygalomorphae are characterized by the vertical orientation of their chelicerae and the possession of four book lungs.

Infraorder Araneomorphae

Most, if not all, of the spiders one is likely to encounter in everyday life belong to infraorder Araneomorphae. It includes a wide range from the spiders that weave their distinctive orb webs in the garden, the more chaotic-looking webs of the cobweb spiders that frequent window frames and the corners of rooms, the crab spiders that lurk waiting for nectar- and pollen-gathering insects on flowers, to the jumping spiders that patrol the outside walls of a dwelling, and so on. They are characterized by having chelicerae whose tips approach each other as they bite, and (usually) having one pair of book lungs.

Some important spider families are :

- Pholcidae (daddy long-legs spiders)

These spiders are frequently seen in cellars. When light contact disturbs their web their characteristic response is to set the entire web moving the way a person would jump up and down on a trampoline. It is unclear why they cause their webs to vibrate in this way; moving their webs back and forward may increase the possibility that insects flying close by may be ensnared, or the rapid gyrations caused by the spider in its web may make the spider harder to target by predators.

- Salticidae (jumping spiders)

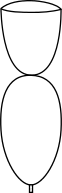

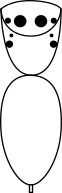

The family Salticidae, commonly called jumping spiders, have a characteristic cephalothorax shape, as shown in the diagram below. They have eight eyes like most spiders, two of them very prominent, and excellent vision. Their maximum size is perhaps 13/16 inch (20 mm), but many species are much smaller than that. The largest North American species such as Phidippus regius, P. octopunctatis, etc., are so heavy bodied that they cannot jump far. The smaller species of jumping spider can jump many times their own body length. They hunt by first getting within range of a prey animal such as a fly, securing a silken "climbing rope" to their current perch, and then jumping onto their prey and biting it. Many seem to take unerring aim at the neck of their prey. Should they jump from one twig to another in an attempt to capture prey and miss or get knocked off the second twig by their struggling prey then they are protected from falling by their silken lifeline. At night these spiders usually retreat to a silken "puptent" that they construct for their own protection and, when needed, as a place to deposit their eggs. They are frequently seen in sunlit areas on walls, tree trunks, and other such vertical surfaces.

"Squared-off" cephalothorax of the jumping spiders. |

Eye pattern of the jumping spiders. |

Classification above families

Spiders were long classified into families that were then grouped into superfamilies, some of which were in turn placed into a number of higher taxa below the level of infraorder. When more rigorous approaches, such as cladistics, were applied to spider classification, it became clear that most of the major groupings used in the 20th century were not supported. Many were based on shared characters inherited from the ancestors of multiple clades (plesiomorphies), rather than being distinctive characters originating in the ancestors of that clade only (apomorphies). According to Jonathan A. Coddington in 2005, "books and overviews published prior to the last two decades have been superseded".[20] Listings of spiders, such as the World Spider Catalog, currently ignore classification above the family level.[20][21]

At the higher level, the phylogeny of spiders is now often discussed using informal clade names, such as the "RTA clade",[22] the "Oval Calmistrum" clade or the "Divided Cribellum" clade.[23] Older names previously used formally are used as clade names, e.g. Entelegynae and Orbiculariae.[24]

Table of families

| Genera | 1 | ≥2 | ≥10 | ≥100 |

| Species | 1–9 | ≥10 | ≥100 | ≥1000 |

Notes

- Species counts from World Spider Catalog (2020, Currently valid spider genera and species), family classification from Coddington (2005, p. 20).

- Unless otherwise shown, currently accepted families and counts based on the World Spider Catalog version 21.5 as of 31 October 2020.[25] In the World Spider Catalog, "species" counts include subspecies. Assignment to sub- and infraorders based on Coddington (2005, p. 20) (when given there).

References

- Platnick & Raven (2013), p. 600.

- Platnick & Raven (2013), p. 597.

- Bond et al. (2014).

- Coddington (2005).

- Coddington (2005), p. 20.

- Griswold et al. (2005).

- Blackledge et al. (2009), p. 5232.

- Bond et al. (2014), p. 1766.

- Coddington & Levi (1991), p. 577.

- Eberhard & Huber (2010), pp. 256–257.

- Eberhard & Huber (2010), p. 250.

- Coddington (2005), p. 22.

- Michalik & Ramírez (2014), p. 312.

- Agnarsson, Coddington & Kuntner (2013), p. 40.

- Hormiga & Griswold (2014), p. 488.

- Hormiga & Griswold (2014), p. 505.

- Blackledge et al. (2009), Fig. 3.

- Bond et al. (2014), Fig 3. Web types defined as Blackledge et al. (2009, Fig. 3)

- Bond et al. (2014), p. 1768.

- Coddington (2005), p. 24.

- World Spider Catalog (2020).

- Hormiga & Griswold (2014), p. 491.

- Ramírez (2014), p. 4.

- Hormiga & Griswold (2014), pp. 490–491.

- World Spider Catalog (2020), Currently valid spider genera and species.

Bibliography

- Agnarsson, Ingi; Coddington, Jonathan A. & Kuntner, Matjaž (2013). "Systematics : Progress in the study of spider diversity and evolution". In Penney, David (ed.). Spider research in the 21st century: trends & perspectives. Manchester, UK: Siri Scientific Press. ISBN 978-0-9574530-1-2.

- Blackledge, Todd A.; Scharff, Nikolaj; Coddington, Jonathan A.; Szüts, Tamas; Wenzel, John W.; Hayashi, Cheryl Y. & Agnarsson, Ingi (2009). "Reconstructing web evolution and spider diversification in the molecular era". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (13): 5229–5234. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5229B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901377106. PMC 2656561. PMID 19289848.

- Bond, Jason E.; Garrison, Nicole L.; Hamilton, Chris A.; Godwin, Rebecca L.; Hedin, Marshal & Agnarsson, Ingi (2014). "Phylogenomics Resolves a Spider Backbone Phylogeny and Rejects a Prevailing Paradigm for Orb Web Evolution". Current Biology. 24 (15): 1765–1771. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.034. PMID 25042592.

- Coddington, Jonathan A. (2005). "Phylogeny and classification of spiders" (PDF). In Ubick, D.; Paquin, P.; Cushing, P.E. & Roth, V. (eds.). Spiders of North America: an identification manual. American Arachnological Society. pp. 18–24. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- Coddington, Jonathan A. & Levi, Herbert W. (1991). "Systematics and evolution of spiders (Araneae)". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 22: 565–592. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.003025. JSTOR 2097274.

- Eberhard, W.G. & Huber, B.A. (2010). "Spider genitalia: precise manoeuvers with a numb structure in a complex lock" (PDF). In Leonard, Janet L. & Córdoba-Aguilar, Alex (eds.). The evolution of primary sexual characters in animals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971703-3. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- Griswold, C.E.; Ramirez, M.J.; Coddington, J.A. & Platnick, N.I. (2005). "Atlas of phylogenetic data for entelegyne spiders (Araneae: Araneomorphae: Entelegynae) with comments on their phylogeny" (PDF). Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 56 (Suppl. 2): 1–324. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- Hormiga, Gustavo & Griswold, Charles E. (2014). "Systematics, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Orb-Weaving Spiders". Annual Review of Entomology. 59 (1): 487–512. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162046. PMID 24160416.

- Michalik, Peter & Ramírez, Martín J. (2014). "Evolutionary morphology of the male reproductive system, spermatozoa and seminal fluid of spiders (Araneae, Arachnida)–Current knowledge and future directions". Arthropod Structure & Development. 43 (4): 291–322. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2014.05.005. PMID 24907603.

- Platnick, Norman I. & Raven, Robert J. (2013). "Spider Systematics: Past and Future". Zootaxa. 3683 (5): 595–600. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3683.5.8.

- Ramírez, Martín J. (2014). The morphology and phylogeny of dionychan spiders (Araneae, Araneomorphae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 390. hdl:2246/6537.

- World Spider Catalog (2020). "World Spider Catalog version 21.5". Natural History Museum Bern. Retrieved 2020-10-31.