State media

State media, state-controlled media or state-owned media is media for mass communication[1] that is under financial and editorial control of a country's government, directly or indirectly. These news outlets may be the sole media outlet or may exist in competition with corporate and non-corporate media.

| Journalism |

|---|

| Areas |

| Genres |

|

| Social impact |

| News media |

| Roles |

|

State media is not to be confused with public-sector media (state-funded), which is "funded directly or indirectly by the state or government but over which the state does not have tight editorial control."[1]

Overview

Its content, according to some sources, is usually more prescriptive, telling the audience what to think, particularly as it is under no pressure to attract high ratings or generate advertising revenue[2] and therefore may cater to the forces in control of the state as opposed to the forces in control of the corporation, as described in the propaganda model of the mass media. In more controlled regions, the state may censor content which it deems illegal, immoral or unfavourable to the government and likewise regulate any programming related to the media; therefore, it is not independent of the governing party.[3] In this type of environment, journalists may be required to be members or affiliated with the ruling party, such as in the former communist countries, the Soviet Union or North Korea.[2] Within countries that have high levels of government interference in the media, it may use the state press for propaganda purposes:

- to promote the regime in a favourable light,

- vilify opposition to the government by launching smear campaigns

- giving skewed coverage to opposition views, or

- act as a mouthpiece to advocate a regime's ideology.

Additionally, the state-controlled media may only report on legislation after it has already become law to stifle any debate.[4] The media legimitises its presence by emphasising "national unity" against domestic or foreign "aggressors".[5] In more open and competitive contexts, the state may control or fund its own outlet and is in competition with opposition-controlled and/or independent media. The state media usually have less government control in more open societies and can provide more balanced coverage than media outside of state control.[6]

State media outlets usually enjoy increased funding and subsidies compared to private media counterparts, but this can create inefficiency in the state media.[7] However, in the People's Republic of China, where state control of the media is high, levels of funding have been reduced for state outlets, which have forced the Party media to sidestep official restrictions on content or publish "soft" editions, such as weekend editions, to generate income.[8]

Theories of state ownership

Two contrasting theories of state control of the media exist; the public interest or Pigouvian theory states that government ownership is beneficial, whereas the public choice theory suggests that state control undermines economic and political freedoms.

Public interest theory

The public interest theory is also referred to as the Pigouvian theory[9] and states that government ownership of media is desirable.[10] Three reasons are offered. Firstly, the dissemination of information is a public good, and to withhold it would be costly even if it is not paid for. Secondly, the cost of the provision and dissemination of information is high, but once costs are incurred, marginal costs for providing the information are low and so are subject to increasing returns.[11] Thirdly, state media ownership can be less biased, more complete and accurate if consumers are ignorant and in addition to private media that would serve the governing classes.[11] However, Pigouvian economists, who advocate regulation and nationalisation, are supportive of free and private media.[12]

Public choice theory

The public choice theory asserts that state-owned media would manipulate and distort information in favour of the ruling party and entrench its rule and prevent the public from making informed decisions, which undermines democratic institutions.[11] That would prevent private and independent media, which provide alternate voices allowing individuals to choose politicians, goods, services, etc. without fear from functioning. Additionally, that would inhibit competition among media firms that would ensure that consumers usually acquire unbiased, accurate information.[11] Moreover, this competition is part of a checks-and-balances system of a democracy, known as the Fourth Estate, along with the judiciary, executive and legislature.[11]

Determinants of state control

Both theories have implications regarding the determinants and consequences of ownership of the media.[13] The public interest theory suggests that more benign governments should have higher levels of control of the media which would in turn increase press freedom as well as economic and political freedoms. Conversely, the public choice theory affirms that the opposite is true - "public spirited", benevolent governments should have less control which would increase these freedoms.[14]

Generally, state ownership of the media is found in poor, autocratic non-democratic countries with highly interventionist governments that have some interest in controlling the flow of information.[15] Countries with "weak" governments do not possess the political will to break up state media monopolies.[16] Media control is also usually consistent with state ownership in the economy.[17]

As of 2002, the press in most of Europe (with the exception of Belarus) is mostly private and free of state control and ownership, along with North and South America.[18] The press "role" in the national and societal dynamics of the United States and Australia has virtually always been the responsibility of the private commercial sector since these countries' earliest days.[19] Levels of state ownership are higher in some African countries, the Middle East and some Asian countries (with the exception of Japan, India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Nepal, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand where large areas of private press exist.) Full state monopolies exist in Burma (under the military rule) and North Korea.[18]

Consequences of state ownership

Issues with state media include complications with press freedom and journalistic objectivity. According to Christopher Walker in the Journal of Democracy, "authoritarian or totalitarian media outlets" such as China's CCTV, Russia's RT and Venezuela's TeleSUR take advantage of both domestic and foreign media due to the censorship under regimes in their native countries and the openness of democratic nations to which they broadcast.[20]

Press freedom

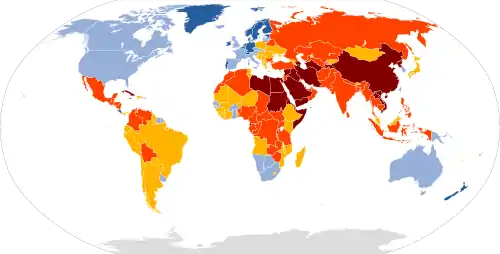

|

Very serious situation

Difficult situation

|

Noticeable problems

Satisfactory situation

|

Good situation

Not classified / No data

|

"Worse outcomes" are associated with higher levels of state ownership of the media, which would reject Pigouvian theory.[22] The news media are more independent and fewer journalists are arrested, detained or harassed in countries with less state control.[23] Harassment, imprisonment and higher levels of internet censorship occur in countries with high levels of state ownership such as Singapore, Belarus, Burma, Ethiopia, China, Iran, Syria, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.[23][24] However this is not always the case, the public broadcaster in the United Kingdom, the BBC, although funded by the public licence fee and government, is editorially independent from state control and acts with similar freedoms to the privately owned media.[25] Countries with a total state monopoly in the media like North Korea and Laos experience a "Castro effect", where state control is powerful enough that no journalistic harassment is required in order to restrict press freedom.[23]

Civil and political rights

The public interest theory claims state ownership of the press enhances civil and political rights; whilst under the public choice theory, it curtails them by suppressing public oversight of the government and facilitating political corruption. High to absolute government control of the media is primarily associated with lower levels of political and civil rights, higher levels of corruption, quality of regulation, security of property and media bias.[24][26] State ownership of the press can compromise election monitoring efforts and obscure the integrity of electoral processes.[27] Independent media sees higher oversight by the media of the government. For example, reporting of corruption increased in Mexico, Ghana and Kenya after restrictions were lifted in the 1990s, but government-controlled media defended officials.[28][29]

Economic freedom

It is common for countries with strict control of newspapers to have fewer firms listed per capita on their markets[30] and less developed banking systems.[31] These findings support the public choice theory, which suggests higher levels of state ownership of the press would be detrimental to economic and financial development.[24]

Notes

- Webster, David. Building Free and Independent Media (August 1992).

- Silverblatt & Zlobin, 2004, p. 22

- Price, Rozumilowicz & Verhulst, 2002, p. 6

- Karatnycky, Motyl & Schnetzer, 2001, p. 105, 106, 228, 384

- Hoffmann, p. 48

- Karatnycky, Motyl & Schnetzer, 2001, p. 149

- Stability Pact Anti-Corruption Initiative, 2002, p. 78

- Sen & Lee, 2008, p. 14

- Coase, R. H. British Broadcasting, 1950. The following argument was formulated by the BBC in support of maintaining publicly subsidised radio and television in the United Kingdom

- Djankov, McLeish, Nenova & Shleifer, 2003, p. 341

- Djankov, McLeish, Nenova & Shleifer, 2003, p. 342

- Lewis, 1955; Myrdal, 1953

- Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes & Sheleifer, 2002, 28-29

- Djankov, McLeish, Nenova & Shleifer, 2003, p. 343

- Djankov, 2002, p. 21

- Price, 2004, p. 195

- Djankov, 2002, p. 20

- Djankov, 2002, p. 19

- Hoffmann-Riem, 1996, p. 3

- Walker, Christopher (2016). "The Authoritarian Threat: The Hijacking of "Soft Power"". Journal of Democracy. 27 (1): 49–63. doi:10.1353/jod.2016.0007. ISSN 1086-3214.

- "2020 World Press Freedom Index". Reporters Without Borders. 2020.

- Djankov, McLeish, Nenova & Shleifer, 2003, p. 344

- Djankov, 2002, p. 23

- Djankov, McLeish, Nenova & Shleifer, 2003, p. 367

- BBC Charter. A strong BBC, independent of government, March 2005

- Djankov, 2002, p. 24

- Merloe, Patrick (2015). "Election Monitoring Vs. Disinformation". Journal of Democracy. 26 (3): 79–93. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0053. ISSN 1086-3214.

- Simon, 1998

- Djankov, 2002, p. 25

- La Porta et al, 1997

- Beck, Demirguc-Kunt & Levine, 1999

References

- Beck, Thorsten; Demirguc-Kunt, Asli & Levine, Ross. A New Database on Financial Development and Structure. Policy Research Working paper 2146, World Bank, Washington D.C., 1999.

- Djankov, Simeon. Who owns the media? World Bank Publications, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7060-4285-6.

- Djankov, Simeon; La Porta, Rafael; Lopez-de-Silanes & Shleifer, Andrei. Regulation of Entry. The Quarterly of Economics, 117(1), pp. 1–37. 2002.

- Djankov, Simeon; McLeish, Caralee; Nenova, Tatiana & Shleifer, Andrei. Who owns the media? Journal of Law and Economics, 46, pp. 341–381, 2003.

- Hoffmann, Bert. The politics of the Internet in Third World development: challenges in contrasting regimes with case studies of Costa Rica and Cuba. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-94959-0.

- Hoffmann-Riem, Wolfgang. Regulating Media: The Licensing and Supervision of Broadcasting in Six Countries. Guilford Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1-57230-029-3,

- Islam, Roumeen; Djankov, Simeon & McLiesh, Caralee. The right to tell: the role of mass media in economic development. World Bank Publications, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8213-5203-8.

- Karatnycky, Adrian; Motyl, Alexander; Schnetzer, Amanda; Freedom House. Nations in transit, 2001: civil society, democracy, and markets in East Central Europe and the newly independent states. Transaction Publishers, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7658-0897-4.

- La Porta, Rafael; Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, Andrei & Vishny, Robert. Legal Determinants of External Finance. Journal of Finance, 52(3), 1131–1150, 1997.

- Lewis, Arthur. The Theory of Economic Growth. Routledge, 2003 (originally published 1955). ISBN 978-0-415-31301-8.

- Myrdal, Gunnar. The Political Element in the Development of Economic Theory. Transaction Publishers, 1990 (originally published 1953). ISBN 978-0-88738-827-9.

- Price, Monroe. Media and Sovereignty: The Global Information Revolution and Its Challenge to State Power. MIT Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-262-66186-7.

- Price, Monroe; Rozumilowicz, Beata & Verhulst, Stefaan. Media reform: democratizing the media, democratizing the state. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0-415-24353-7.

- Sen, Krishna; Lee, Terence. Political regimes and the media in Asia. Routledge, 2008. ISBN 978-0-415-40297-2.

- Simon, Joel. Hot on the Money Trail. Columbia Journalism Review, 37(1), pp. 13–22, 1998.

- Silverbatt, Art; Zlobin, Nikolai. International communications: a media literacy approach. M.E. Sharpe, 2004. ISBN 978-0-7656-0975-5.

- Stability Pact Anti-Corruption Initiative, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Anti-corruption measures in South Eastern Europe: civil society's involvement. OECD Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-92-64-19746-6.