Steamboats on the Yangtze River

After thousands of years of junk and sampan traffic on the Yangtze River (Jiang), river steamers were introduced by Europeans during the mid- to late-nineteenth century. The age of the steamer lasted nearly 150 years—from 1835 to 1980—and had lasting impacts on China, where river trade was essential to the economy due to the poor road network and few railways.

First Opium War

The first merchant steamer in China, the Jardine, was built to order for the firm of Jardine, Matheson & Co. in 1835. She was a small vessel intended for use as a mail and passenger carrier between Lintin Island, Macao, and Whampoa. However, the Chinese, draconian in their application of the rules relating to foreign vessels, were unhappy about a "fire-ship" steaming up the Canton River. The acting Governor-General of Kwangtung issued an edict warning that she would be fired on if she attempted the trip.[1] On the Jardine's first trial run from Lintin Island the forts on both sides of the Bogue opened fire and she was forced to turn back. The Chinese authorities issued a further warning insisting that the ship leave Chinese waters. The Jardine in any case needed repairs and was sent to Singapore.[2]

Subsequently, Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary decided mainly on the "suggestions" of William Jardine to declare war on China. In mid-1840, a large fleet of warships appeared on the China coast, and with the first cannonball fired at a British ship, the Royal Saxon, the British started the first of the Opium Wars. Royal Navy warships destroyed numerous shore batteries and Chinese warships, laying waste to several coastal forts along the way. Eventually, they pushed their way up north close enough to threaten the Imperial Palace in Peking itself. The Chinese imperial government quickly gave in to the demands of the British. British military superiority was clearly evident during the conflict. British warships, constructed using such innovations as steam power combined with sail and the use of iron in shipbuilding, wreaked havoc on Chinese junks; such ships (like the Nemesis) were not only virtually indestructible but also highly mobile and able to support a gun platform with very heavy guns. In addition, the British troops were armed with modern muskets and cannons, unlike the Qing forces. After the British captured Canton, they sailed up the Yangtze and seized the tax barges, a significant blow to the Imperial government as it slashed the revenue of the imperial court in Beijing to just a small fraction of what it had been.[3]

In 1842 the Qing authorities sued for peace, which concluded with the Treaty of Nanking signed on a warship in the river, negotiated in August of that year and ratified in 1843. In the treaty, China was forced to pay an indemnity to Britain, open five treaty ports to all foreign nations, and cede Hong Kong to Queen Victoria. In the supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, the Qing Empire also recognized Britain as an equal to China and gave British subjects extraterritorial privileges in treaty ports. The China Navigation Company was an early shipping company founded in 1876 in London, initially to trade up the Yangtze River from their Shanghai base with passengers and cargo. Chinese coastal trade started shortly after, and in 1883 a regular service to Australia was initiated.[4]

US involvement

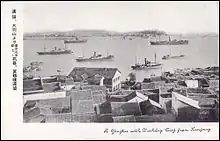

The US, at the same time, wanted to protect its interests and expand trade, ventured the USS Wachusett six-hundred miles up the river to Hankow about 1860. While the USS Ashuelot, a sidewheeler, made her way up the river to Ichang in 1874. The first USS Monocacy, a sidewheel gunboat, began charting the Yangtze River in 1871. The first USS Palos, an armed tug, was on the Asiatic Station into 1891, cruising the Chinese and Japanese coasts, visiting the open treaty ports and making occasional voyages up the Yangtze River. From June to September 1891, anti-foreign riots up the Yangtze forced the warship to make an extended voyage as far as Hankow, 600 miles upriver. Stopping at each open treaty port, the gunboat cooperated with naval vessels of other nations and repaired damage. She then operated along the north and central China coast and on the lower Yangtze until June 1892. With the cessation of bloodshed with the Taiping Rebellion, Europeans put more steamers on the river. The French, eager to secure their share, engaged the Chinese in war over the rule of Vietnam. The Sino-French Wars of the 1880s emerged with the Battle of Shipu having French cruisers in the lower Yangtze. The Chinese had the Nanyang Fleet based at Shanghai and was harassed by French cruisers but saw little action.

Boxer Rebellion

A Chinese song From the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 sums up the Middle Kingdom's attitude to Europeans, Americans and the Japanese.

It will not be difficult to exterminate the foreign devils

then.

Push aside the railway track.

Pull out the telegraph poles ;immediately after this destroy the steamers.

The Boxer Rebellion was a disaster for China with more foreign involvement in the country. Most of the warring took place in Peking and thus far from the Yangtze River.

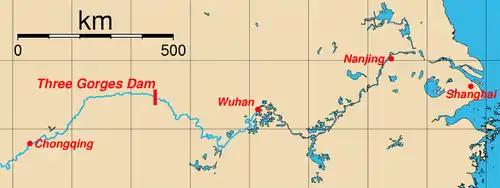

Chinese ships on the Yangtze

Yichang or Ichang, 1,600 km (1,000 mi) from the sea, is the head of regular navigation for river steamers; oceangoing vessels may navigate the river to Hankow, a distance of almost 1,000 km (almost 600 mi) from the sea. For about 320 km (about 200 mi) inland from its mouth, the river is virtually at sea level.

The Chinese Government, too, had steamers. It had its own naval fleet, the Beiyang Fleet, which fell prey to the French fleet. The Chinese rebuilt its fleet, only to have it ravaged by another war with Japan in 1895, the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, and ongoing inefficiency and corruption. Chinese companies ran their own steamers, but were second tier to European operations at the time.

Commercial involvement

The commercial firms of Jardine Matheson, Butterfield and Swire, and Standard Oil had their own steamers on the river. Until 1881, the India and China coastal and river services were operated by several companies. In that year, however, these were merged into the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company, Ltd., a public company under the management of Jardines. The Jardine company pushed inland up the Yangtze River on which a specially designed fleet was built to meet all requirements of the river trade. For many years, this fleet gave unequalled service. Jardines established an enviable reputation for the efficient handling of shipping. As a result, the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company invited the firm to attend to the Agency of their Shire Line which operated in the Far East.

With the Treaty Ports, the European powers and Japan were allowed to float navy ships into China's internal waters. The British, US and French did this. A full international fleet featured on Chinese waters: Austro-Hungarians, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, and German navy ships came to Shanghai and the treaty ports.

The French Banque de l'Indochine was among the members of a western banking syndicate given control of China’s finances. French civil servants took control of China's postal service. In 1901 the French gunboat Orly was detached from the Far East Squadron for a cruise up the Yangtze Kiang, under the command of Lieutenant de Vaisseau Emile Hourst . The Olry was accompanied by the steam launch Takiang as far as Chunking which it reached on November 13, thus becoming the first French gunboat to reach the Upper Yangtze river. Subsequently, Lieutenant de Vaisseau Emile Hourst continued on in a vain search for an inland waterway linking Szechwan with Tonkin. The Olry very nearly was taken in a sinking in the Three Gorges in 1911. It hit the shore and damaged its rudder; out of control, it nearly foundered. However, excellent boatmanship and improvisation saved the day and the vessel. The Orly was followed by several French gunboats based in Shanghai and patrolling the Yangtze River up till the Second World War

The Japanese engaged in open war with the Chinese twice, and Russians twice, over conquest of the Chinese Qing empire—in the First and Second Sino-Japanese War 1895, and 1905; and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. Incidentally, both the French and Japanese navies were heavily involved in running Vietnamese opium and narcotics to Shanghai, where it was refined into morphine. It was then trans-shipped by liner back to Marseilles and France (i.e. French Connection) for processing in Germany and eventual sale in the US or Europe.

Steamers came late to the upper river. The Three Gorges had 404 individual rapids and the strong 15 knot current hindered navigation. Archibald Little attempted a voyage with the Lee-Chuan, and the Kuling, delays and weak engines meant that he only succeeded in the first vessel in 1898. Little soon built the first truly successful boat, the Pioneer, in about 1899. In 1898, Little persuaded Captain Samuel Cornell Plant to come out to China to lend his expertise. Captain Plant had just completed navigation of Persia's Upper Karun River and took up Little's offer to assess the Upper Yangtze on Leechuan at the end of 1898. With Plant's design input, Little had SS Pioneer built with Plant in command. In June 1900, Plant was the first to successfully pilot a merchant steamer on the Upper Yangtze from Yichang to ChongqingShe plied the river for two more decades and was even the flagship for the Royal Navy on the China Station. There were a few commercial steamers on the upper river at the turn of the century and the Boxer Rebellion period.

In 1909 the gunboat USS Samar changed station to Shanghai, where she regularly patrolled the lower Yangtze River up to Nanking and Wuhu. Following anti-foreign riots in Changsha in April 1910, which destroyed a number of missions and merchant warehouses, Samar sailed up the Yangtze River to Hankow and then Changsa to show the flag and help restore order. The gunboat was also administratively assigned to the United States Asiatic Fleet that year, which had been re-established by the Navy to better protect, in the words of the Bureau of Navigation, "American interests in the Orient." After returning to Shanghai in August, she sailed up river again the following summer, passing Wuhu in June but then running aground off Kichau on 1 July 1911. After staying stuck in the mud for two weeks, Samar broke free and sailed back down river to take on coal. Returning upriver, the gunboat reached Hankow in August and Ichang in September, where she overwintered, owing to both the dry season and the outbreak of rebellion at Wuchang in October 1911. Tensions eased, and the gunboat turned downriver in July 1912, arriving at Shanghai in October. Samar patrolled the lower Yangtze after fighting broke out in the summer 1913, a precursor to a decade of conflict between provincial warlords in China. In 1919, she was placed on the disposal list at Shanghai following a collision with a Yangtze river steamer that damaged her bow.

The private China Merchants Shipping Company was founded by Hong Kong merchants and ran steamers on the river, as did the Yangtze Rapid Steamer Company after 1920.

The seamen's strikes were staged by the seamen at Hong Kong and by the crews of the Yangtse River steamers early in 1922. The Hong Kong seamen held out for eight weeks. After a bitter and bloody struggle, the British imperialist authorities in Hong Kong were finally forced to raise wages, lift the ban on the Seamen's Union, release the arrested workers and indemnify the families of the martyrs. The crews of the Yangtze steamers went on strike soon afterwards, carried on the struggle for two weeks and also won victory.

Increased US presence

The Spanish built boats that we absorbed into the US Navy after the loss of the Philippines were replaced by newer vessels for US Navy service in the 1920s. Luzon and Mindanao were the largest, Oahu and Panay next in size, and Guam and Tutuila the smallest. China in the first fifty years of the twentieth century, was in low-grade chaos. Warlords, revolutions, natural disasters, civil war and invasions contributed. Yangtze boats were involved in the Nanking Incident in 1927 when the Communists and Nationalists broke into open war. Chiang Kai-shek's massacre of the Communists in Shanghai in 1927 furthered the unrest, US Marines with tanks were landed.

River steamers were popular targets for both Nationalists and Communists, and peasants who would take periodic pot-shots at vessels. During the course of service the second USS Palos protected American interests in China down the entire length of the Yangtze, at times convoying U.S. and foreign vessels on the river, evacuating American citizens during periods of disturbance and in general giving credible presence to U.S. consulates and residences in various Chinese cities. In the period of great unrest in central China in the 1920s, Palos was especially busy patrolling the upper Yangtze against bands of warlord soldiers and outlaws. The warship engaged in continuous patrol operations between Yichang and Chongqing throughout 1923, supplying armed guards to merchant ships, and protecting Americans at Chungking while that city was under siege by a warlord army.

Standard Oil ran the tankers Mei Ping, Mei An, and Mei Hsia on the river, in addition to many motor barges, launches, tugboats and other tankers. These three tankers, the largest in the oil company's fleet, operated on the river until 1937 when they were bombed by the Japanese in the USS Panay incident.[5] In the second half of 1934 Settle arrived in China, tasked with sailing USS Palos (PG-16) 1,300 miles (2,100 km) up the Yangtze River from Wusong to Chongqing. Palos, a gunboat stationed around Shanghai since 1914, had recently been refitted and over time became twice as heavy against her original displacement (340 vs. 180 tons), making her hardly capable of the upstream journey. In 1929 alone, of 67 Yangtze steamers three were totally destroyed by the rapids with 47 casualties; a thousand junk sailors perished every year.

Royal Navy boats on the Yangtze River

Of course, the Royal Navy had three generations of gunboats on the Yangtze River spanning fifty years. The first were the Heron-class river gunboats, of which HMS Nightingale [1897-98]; and HMS Robin, HMS Sandpiper, HMS Snipe served on Yangtze and West Rivers until 1914 and were sold in 1919. Later, in the Woodcock Class of gunboats came into service: these included the Woodcock, Moorhen, Teal and Widgeon.

The Insect-class gunboats, built in Britain for service on the Danube in 1915, were moved to the China Station and the Yangtze River in the 1920s. Concomitant to the Insect class were the Dragonfly class of smaller boats—Dragonfly, Grasshopper, Locust and Mosquito. Unfortunately, most of these became casualties of war in 1942 with the Japanese attacks.

In 1926 the Wanhsien incident, brought the attention of the chaotic political situation of China. A local warlord seized the Swire steamer Wahsien and held the ship and her officers for ransom. British gunboats came to the support of the Wahsien. The officers escaped, and the gunboats shelled the shoreline, from where the Chinese were firing rifles and artillery at the boats. (See HMS Cockchafer (1915).)

Japanese takeover

On January 28, 1932, the Japanese attacked the Chinese nationalists around Shanghai. Around midnight, Japanese carrier aircraft bombed the city in the first major aircraft carrier action in the Far East. Three thousand Japanese troops proceeded to attack various targets, such as train stations, around the city. From 1931 to 1933, the cruiser Tenryū was assigned to patrol the Yangtze River and was thus in combat during the January 28 Incident at Shanghai in 1932. The Battle of Shanghai of 1937 was the first of the twenty-two major engagements fought between the National Revolutionary Army, Republic of China and the Imperial Japanese Army, Empire of Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the entire war. On August 13, 1937, the Japanese and Chinese exchanged fire in Shanghai in the ongoing war. The Chinese 88th Division retaliated with mortar attacks. Sporadic shooting continued through the day until 4pm, when the Japanese headquarters ordered the naval ships of the Third Fleet, stationed in the Yangtze and the Huangpu River to open fire on Chinese positions in the city. In the late night of August 13, Chiang Kai-shek ordered Zhang Zhizhong to begin the Chinese offensive the next day. On August 22, the Japanese 3rd, 8th, and 11th Divisions made an amphibious assault under cover from naval bombardments and proceeded to land in Chuanshakou (川沙口), Shizilin (獅子林), and Baoshan (寶山), towns on the northeast coast some fifty kilometers away from downtown Shanghai. Japanese landings in northeast Shanghai suburban areas meant that many Chinese troops, who were deployed in Shanghai's urban center, had to be redeployed to coastal regions to counter the landings.

The Japanese navy shelled Shanghai from its warships. It used ships to support the Army in Shanghai and Nanking. A task force of over 100 ships was used to move forces upriver and take Hankow (now Wuhan) in the summer of 1938. Japanese aircraft sank two Chinese naval cruisers guarding the river during these actions.

With the Japanese advance into the east coast of China in 1937, enterprises and numerous people withdrew from Wuhan to the west and Sichuan. The Kuomintang navy undertook the responsibility of defending the Yangtze River and covering the withdrawal. On 24 October, while patrolling the waters of the Yangtze River near the town of Jinkou, in Wuchang (Jiangxia, Wuhan), the Zhongshan was bombed by six Japanese aircraft . The aircraft dived, strafed and bombed the Zhongshan. Despite shooting down two of the aircraft, the Zhongshan eventually sank due to the serious damage she had sustained. Twenty-five Chinese officers and soldiers were killed in the battle.

The USS Panay Incident

The most infamous incident was the Panay incident, when USS Panay and HMS Bee were dive-bombed by Japanese aircraft in late 1937 during the Rape of Nanking. The tanker Mei Ping was sunk in the same attack. After that outrage, much of the population and government of China fled inland to the wartime capital at Chungking, thousands of journeys were made by steamer. Whole factories, libraries, and households were picked up and moved up the perilous river. Even the National Palace Art Collection, the storied treasure of the Chinese Emperors, was boxed and moved inland. Junks, carts, and sampans were pressed into service, and cargoes kedged through the Three Gorge Rapids, with ropes and gangs of men.

In 1939 the Japanese put further restrictions on foreign shipping on the lower Yangtze, trying to undo the near British Monopoly. The Europeans were forced to leave the Yangtze River with the Japanese takeover of the Settlements in 1941. The Japanese sank HMS Peterel with naval gunfire. The former steamers were either sabotaged or pressed into Japanese or Chinese service.

The Post War Period

After the Japanese surrender, the Communists and the Nationalists continued their civil war. The Americans and British tried to re-instate their presence as it had been before the war, but following the communist takeover in 1949, non-Chinese shipping companies ceased operations on the Yangtze.

In 1949, the SS Shenking of the Butterfield and Swire Line made an epic rescue of stranded civilians from Shanghai, running them across the China Sea to Keelung, Formosa.

One river ferry sank in 1947, drowning 400 people.

Mao and the Chinese Communist Party journeyed upriver by steamer in 1959 to Lushan to the Lushan Conference to discuss the Great Leap Forward. However, little is known in the west about this period, as China became a closed country. Many retired North American steamers were sent to Japan or Taiwan for scrapping. Some were pressed into mainland china service. By the 1970s China embarked on its own ship and engine building programs, and steamers have since been replaced by diesel tugs, freighters and ferry boats.

See also

References

- Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 51 (2): 231–263. doi:10.1086/241899. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Blue, A.D. (1973). "Early Steamships in China" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 13: 45–57. ISSN 1991-7295. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 51 (2): 231–263. doi:10.1086/241899. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 51 (2): 231–263. doi:10.1086/241899. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Mender, P., Thirty Years a Mariner in the Far East, The Memoirs of Peter Mender, a Standard Oil Ship Captain on China's Yangtze River, ISBN 978-1-60910-498-6

External links

- Jardine, Matheson & Co. and subsidiaries

- China Navigation Co ships 1866-1966

- WikiSwire website