Standard Oil

Standard Oil Co. was an American oil-producing, transporting, refining, marketing company. Established in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller and Henry Flagler as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world of its time.[7] Its history as one of the world's first and largest multinational corporations ended in 1911, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in a landmark case, that Standard Oil was an illegal monopoly.

| Type |

|

|---|---|

| Industry | Oil and gas |

| Successor | 34 successor entities |

| Founded | 1870 |

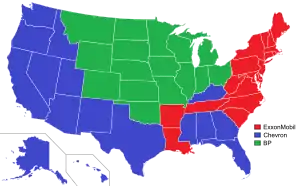

| Defunct | After its dissolution in 1911, the original Standard Oil Co. split into Sohio (now part of BP); ESSO (now Exxon); and SOcal (now Chevron) [2] |

| Headquarters |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Fuel, lubricant, petrochemicals |

Number of employees | 60,000 (1909)[6] |

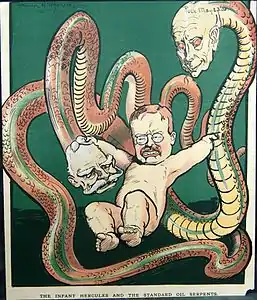

Standard Oil dominated the oil products market initially through horizontal integration in the refining sector, then, in later years vertical integration; the company was an innovator in the development of the business trust. The Standard Oil trust streamlined production and logistics, lowered costs, and undercut competitors. "Trust-busting" critics accused Standard Oil of using aggressive pricing to destroy competitors and form a monopoly that threatened other businesses.

Rockefeller ran the company as its chairman, until his retirement in 1897. He remained the major shareholder, and in 1911, with the dissolution of the Standard Oil trust into 34 smaller companies, Rockefeller became the richest person in modern history, as the initial income of these individual enterprises proved to be much bigger than that of a single larger company. Its successors such as ExxonMobil, Marathon Petroleum, Amoco, and Chevron are still among the companies with the largest revenues in the world. By 1882, his top aide was John Dustin Archbold. After 1896, Rockefeller disengaged from business to concentrate on his philanthropy, leaving Archbold in control. Other notable Standard Oil principals include Henry Flagler, developer of the Florida East Coast Railway and resort cities, and Henry H. Rogers, who built the Virginian Railway.

Founding and early years

Standard Oil's pre-history began in 1863, as an Ohio partnership formed by industrialist John D. Rockefeller, his brother William Rockefeller, Henry Flagler, chemist Samuel Andrews, silent partner Stephen V. Harkness, and Oliver Burr Jennings, who had married the sister of William Rockefeller's wife. In 1870, Rockefeller abolished the partnership and incorporated Standard Oil in Ohio. Of the initial 10,000 shares, John D. Rockefeller received 2,667; Harkness received 1,334; William Rockefeller, Flagler, and Andrews received 1,333 each; Jennings received 1,000, and the firm of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler received 1,000.[8] Rockefeller chose the "Standard Oil" name as a symbol of the reliable "standards" of quality and service that he envisioned for the nascent oil industry.[9]

In the early years, John D. Rockefeller dominated the combine; he was the single most important figure in shaping the new oil industry.[11]:35 He quickly distributed power and the tasks of policy formation to a system of committees, but always remained the largest shareholder. Authority was centralized in the company's main office in Cleveland, but decisions in the office were made in a cooperative way.[12]

The company grew by increasing sales and through acquisitions. After purchasing competing firms, Rockefeller shut down those he believed to be inefficient and kept the others. In a seminal deal, in 1868, the Lake Shore Railroad, a part of the New York Central, gave Rockefeller's firm a going rate of one cent a gallon or forty-two cents a barrel, an effective 71% discount from its listed rates in return for a promise to ship at least 60 carloads of oil daily and to handle load and unload on its own. Smaller companies decried such deals as unfair because they were not producing enough oil to qualify for discounts.

Standard's actions and secret[13] transport deals helped its kerosene price to drop from 58 to 26 cents from 1865 to 1870. Rockefeller used the Erie Canal as a cheap alternative form of transportation—in the summer months when it was not frozen—to ship his refined oil from Cleveland to New York City. In the winter months his only options were the three trunk lines—the Erie Railroad and the New York Central Railroad to New York City, and the Pennsylvania Railroad to Philadelphia.[14] Competitors disliked the company's business practices, but consumers liked the lower prices. Standard Oil, being formed well before the discovery of the Spindletop oil field (in Texas, far from Standard Oil's base in the Midwest) and a demand for oil other than for heat and light, was well placed to control the growth of the oil business. The company was perceived to own and control all aspects of the trade.

South Improvement Company

In 1872, Rockefeller joined the South Improvement Co. which would have allowed him to receive rebates for shipping and drawbacks on oil his competitors shipped. But when this deal became known, competitors convinced the Pennsylvania Legislature to revoke South Improvement's charter. No oil was ever shipped under this arrangement.[15] Using highly effective tactics, later widely criticized, it absorbed or destroyed most of its competition in Cleveland in less than two months and later throughout the northeastern United States.

Hepburn Committee

A. Barton Hepburn was directed by the New York State Legislature in 1879, to investigate the railroads' practice of giving rebates within the state. Merchants without ties to the oil industry had pressed for the hearings. Prior to the committee's investigation, few knew of the size of Standard Oil's control and influence on seemingly unaffiliated oil refineries and pipelines—Hawke (1980) cites that only a dozen or so within Standard Oil knew the extent of company operations. The committee counsel, Simon Sterne, questioned representatives from the Erie Railroad and the New York Central Railroad and discovered that at least half of their long-haul traffic granted rebates, and that much of this traffic came from Standard Oil. The committee then shifted focus to Standard Oil's operations. John Dustin Archbold, as president of Acme Oil Company, denied that Acme was associated with Standard Oil. He then admitted to being a director of Standard Oil. The committee's final report scolded the railroads for their rebate policies and cited Standard Oil as an example. This scolding was largely moot to Standard Oil's interests since long-distance oil pipelines were now their preferred method of transportation.[16]

Standard Oil Trust

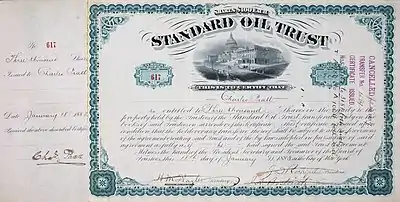

In response to state laws that had the result of limiting the scale of companies, Rockefeller and his associates developed innovative ways of organizing to effectively manage their fast growing enterprise. On January 2, 1882,[17] they combined their disparate companies, spread across dozens of states, under a single group of trustees. By a secret agreement, the existing 37 stockholders conveyed their shares "in trust" to nine trustees:[18] John and William Rockefeller, Oliver H. Payne, Charles Pratt, Henry Flagler, John D. Archbold, William G. Warden, Jabez Bostwick, and Benjamin Brewster.[19] “Whereas some state legislatures imposed special taxes on out-of-state corporations doing business in their states, other legislatures forbade corporations in their state from holding the stock of companies based elsewhere. (Legislators established such restrictions in the hope that they would force successful companies to incorporate—and thus pay taxes—in their state.)” [20][21] Standard Oil's organizational concept proved so successful that other giant enterprises adopted this "trust" form.

In 1885, Standard Oil of Ohio moved its headquarters from Cleveland to its permanent headquarters at 26 Broadway in New York City. Concurrently, the trustees of Standard Oil of Ohio chartered the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey (SOCNJ) to take advantages of New Jersey's more lenient corporate stock ownership laws.

Sherman Antitrust Act

In 1890, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Sherman Antitrust Act (Senate 51–1; House 242-0), a source of American anti-monopoly laws. The law forbade every contract, scheme, deal, or conspiracy to restrain trade, though the phrase "restraint of trade" remained subjective. The Standard Oil group quickly attracted attention from antitrust authorities leading to a lawsuit filed by Ohio Attorney General David K. Watson.

Earnings and dividends

From 1882 to 1906, Standard paid out $548,436,000 in dividends at 65.4% payout ratio. The total net earnings from 1882 to 1906 amounted to $838,783,800, exceeding the dividends by $290,347,800, which was used for plant expansions.

1895–1913

In 1896, John Rockefeller retired from the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey, the holding company of the group, but remained president and a major shareholder. Vice-president John Dustin Archbold took a large part in the running of the firm. In the year 1904, Standard Oil controlled 91% of oil refinement and 85% of final sales in the United States.[23] At this point in time, state and federal laws sought to counter this development with antitrust laws. In 1911, the U.S. Justice Department sued the group under the federal antitrust law and ordered its breakup into 34 companies.

Standard Oil's market position was initially established through an emphasis on efficiency and responsibility. While most companies dumped gasoline in rivers (this was before the automobile was popular), Standard used it to fuel its machines. While other companies' refineries piled mountains of heavy waste, Rockefeller found ways to sell it. For example, Standard created the first synthetic competitor for beeswax and bought the company that invented and produced Vaseline, the Chesebrough Manufacturing Co., which was a Standard company only from 1908 until 1911.

One of the original "Muckrakers" was Ida M. Tarbell, an American author and journalist. Her father was an oil producer whose business had failed because of Rockefeller's business dealings. After extensive interviews with a sympathetic senior executive of Standard Oil, Henry H. Rogers, Tarbell's investigations of Standard Oil fueled growing public attacks on Standard Oil and on monopolies in general. Her work was published in 19 parts in McClure's magazine from November 1902 to October 1904, then in 1904 as the book The History of the Standard Oil Co.

The Standard Oil Trust was controlled by a small group of families. Rockefeller stated in 1910: "I think it is true that the Pratt family, the Payne–Whitney family (which were one, as all the stock came from Colonel Payne), the Harkness-Flagler family (which came into the company together) and the Rockefeller family controlled a majority of the stock during all the history of the company up to the present time."[24]

These families reinvested most of the dividends in other industries, especially railroads. They also invested heavily in the gas and the electric lighting business (including the giant Consolidated Gas Co. of New York City). They made large purchases of stock in U.S. Steel, Amalgamated Copper, and even Corn Products Refining Co.[25]

Weetman Pearson, a British petroleum entrepreneur in Mexico, began negotiating with Standard Oil in 1912–13 to sell his "El Aguila" oil company, since Pearson was no longer bound to promises to the Porfirio Díaz regime (1876–1911) to not to sell to U.S. interests. However, the deal fell through and the firm was sold to Royal Dutch Shell.[26]

In China

Standard Oil's production increased so rapidly it soon exceeded U.S. demand and the company began viewing export markets. In the 1890s, Standard Oil began marketing kerosene to China's large population of close to 400 million as lamp fuel.[27] For its Chinese trademark and brand Standard Oil adopted the name Mei Foo (Chinese: 美孚), (which translates to Mobil).[28][29] Mei Foo also became the name of the tin lamp that Standard Oil produced and gave away or sold cheaply to Chinese farmers, encouraging them to switch from vegetable oil to kerosene. Response was positive, sales boomed and China became Standard Oil's largest market in Asia. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Stanvac was the largest single U.S. investment in Southeast Asia.[30]

The North China Department of Socony (Standard Oil Company of New York) operated a subsidiary called Socony River and Coastal Fleet, North Coast Division, which became the North China Division of Stanvac (Standard Vacuum Oil Company) after that company was formed in 1933.[31] To distribute its products, Standard Oil constructed storage tanks, canneries (bulk oil from large ocean tankers was re-packaged into 5-US-gallon (19 l; 4.2 imp gal) tins), warehouses and offices in key Chinese cities. For inland distribution the company had motor tank trucks and railway tank cars, and for river navigation it had a fleet of low-draft steamers and other vessels.[32]

Stanvac's North China Division, based in Shanghai, owned hundreds of river going vessels, including motor barges, steamers, launches, tugboats and tankers.[33] Up to 13 tankers operated on the Yangtze River, the largest of which were Mei Ping (1,118 gross register tons (GRT)), Mei Hsia (1,048 GRT), and Mei An (934 GRT).[34] All three were destroyed in the 1937 USS Panay incident.[35] Mei An was launched in 1901 and was the first vessel in the fleet. Other vessels included Mei Chuen, Mei Foo, Mei Hung, Mei Kiang, Mei Lu, Mei Tan, Mei Su, Mei Xia, Mei Ying, and Mei Yun. Mei Hsia, a tanker, was specially designed for river duty and was built by New Engineering and Shipbuilding Works of Shanghai, who also built the 500-ton launch Mei Foo in 1912. Mei Hsia ("Beautiful Gorges") was launched in 1926 and carried 350 tons of bulk oil in three holds, plus a forward cargo hold, and space between decks for carrying general cargo or packed oil. She had a length of 206 feet (63 m), a beam of 32 feet (9.8 m), depth of 10 feet 6 inches (3.2 m), and had a bullet-proof wheelhouse. Mei Ping ("Beautiful Tranquility"), launched in 1927, was designed offshore, but assembled and finished in Shanghai. Its oil-fuel burners came from the U.S. and water-tube boilers came from England.[36][37]

In the Middle East

Standard Oil Company and Socony-Vacuum Oil Company became partners in providing markets for the oil reserves in the Middle East. In 1906, SOCONY (later Mobil) opened its first fuel terminals in Alexandria. It explored in Palestine before the World War broke out, but ran into conflict with the local authorities.[38]

Monopoly charges and antitrust legislation

By 1890, Standard Oil controlled 88 percent of the refined oil flows in the United States. The state of Ohio successfully sued Standard, compelling the dissolution of the trust in 1892. But Standard simply separated Standard Oil of Ohio and kept control of it. Eventually, the state of New Jersey changed its incorporation laws to allow a company to hold shares in other companies in any state. So, in 1899, the Standard Oil Trust, based at 26 Broadway in New York, was legally reborn as a holding company, the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey (SOCNJ), which held stock in 41 other companies, which controlled other companies, which in turn controlled yet other companies. According to Daniel Yergin in his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (1990), this conglomerate was seen by the public as all-pervasive, controlled by a select group of directors, and completely unaccountable.[11]:96–98

In 1904, Standard controlled 91 percent of production and 85 percent of final sales. Most of its output was kerosene, of which 55 percent was exported around the world. After 1900 it did not try to force competitors out of business by underpricing them.[39] The federal Commissioner of Corporations studied Standard's operations from the period of 1904 to 1906[40] and concluded that "beyond question ... the dominant position of the Standard Oil Co. in the refining industry was due to unfair practices—to abuse of the control of pipe-lines, to railroad discriminations, and to unfair methods of competition in the sale of the refined petroleum products".[41] Because of competition from other firms, their market share had gradually eroded to 70 percent by 1906 which was the year when the antitrust case was filed against Standard, and down to 64 percent by 1911 when Standard was ordered broken up[42] and at least 147 refining companies were competing with Standard including Gulf, Texaco, and Shell.[43] It did not try to monopolize the exploration and pumping of oil (its share in 1911 was 11 percent).

In 1909, the U.S. Justice Department sued Standard under federal antitrust law, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, for sustaining a monopoly and restraining interstate commerce by:

Rebates, preferences, and other discriminatory practices in favor of the combination by railroad companies; restraint and monopolization by control of pipe lines, and unfair practices against competing pipe lines; contracts with competitors in restraint of trade; unfair methods of competition, such as local price cutting at the points where necessary to suppress competition; [and] espionage of the business of competitors, the operation of bogus independent companies, and payment of rebates on oil, with the like intent.[44]

The lawsuit argued that Standard's monopolistic practices had taken place over the preceding four years:

The general result of the investigation has been to disclose the existence of numerous and flagrant discriminations by the railroads in behalf of the Standard Oil Co. and its affiliated corporations. With comparatively few exceptions, mainly of other large concerns in California, the Standard has been the sole beneficiary of such discriminations. In almost every section of the country that company has been found to enjoy some unfair advantages over its competitors, and some of these discriminations affect enormous areas.[45]

The government identified four illegal patterns: (1) secret and semi-secret railroad rates; (2) discriminations in the open arrangement of rates; (3) discriminations in classification and rules of shipment; (4) discriminations in the treatment of private tank cars. The government alleged:

Almost everywhere the rates from the shipping points used exclusively, or almost exclusively, by the Standard are relatively lower than the rates from the shipping points of its competitors. Rates have been made low to let the Standard into markets, or they have been made high to keep its competitors out of markets. Trifling differences in distances are made an excuse for large differences in rates favorable to the Standard Oil Co., while large differences in distances are ignored where they are against the Standard. Sometimes connecting roads prorate on oil—that is, make through rates which are lower than the combination of local rates; sometimes they refuse to prorate; but in either case the result of their policy is to favor the Standard Oil Co. Different methods are used in different places and under different conditions, but the net result is that from Maine to California the general arrangement of open rates on petroleum oil is such as to give the Standard an unreasonable advantage over its competitors.[46]

The government said that Standard raised prices to its monopolistic customers but lowered them to hurt competitors, often disguising its illegal actions by using bogus supposedly independent companies it controlled.

The evidence is, in fact, absolutely conclusive that the Standard Oil Co. charges altogether excessive prices where it meets no competition, and particularly where there is little likelihood of competitors entering the field, and that, on the other hand, where competition is active, it frequently cuts prices to a point which leaves even the Standard little or no profit, and which more often leaves no profit to the competitor, whose costs are ordinarily somewhat higher.[47]

On May 15, 1911, the US Supreme Court upheld the lower court judgment and declared the Standard Oil group to be an "unreasonable" monopoly under the Sherman Antitrust Act, Section II. It ordered Standard to break up into 34 independent companies with different boards of directors, the biggest two of the companies were Standard Oil of New Jersey (which became Exxon) and Standard Oil of New York (which became Mobil).[48]

Standard's president, John D. Rockefeller, had long since retired from any management role. But, as he owned a quarter of the shares of the resultant companies, and those share values mostly doubled, he emerged from the dissolution as the richest man in the world.[49] The dissolution had actually propelled Rockefeller's personal wealth.[50]

Breakup

By 1911, with public outcry at a climax, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled, in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, that Standard Oil of New Jersey must be dissolved under the Sherman Antitrust Act and split into 34 companies.[51][52] Two of these companies were Standard Oil of New Jersey (Jersey Standard or Esso), which eventually became Exxon, and Standard Oil of New York (Socony), which eventually became Mobil; those two companies later merged into ExxonMobil.

Over the next few decades, both companies grew significantly. Jersey Standard, led by Walter C. Teagle, became the largest oil producer in the world. It acquired a 50 percent share in Humble Oil & Refining Co., a Texas oil producer. Socony purchased a 45 percent interest in Magnolia Petroleum Co., a major refiner, marketer and pipeline transporter. In 1931, Socony merged with Vacuum Oil Co., an industry pioneer dating back to 1866, and a growing Standard Oil spin-off in its own right.[52]

In the Asia-Pacific region, Jersey Standard had oil production and refineries in Indonesia but no marketing network. Socony-Vacuum had Asian marketing outlets supplied remotely from California. In 1933, Jersey Standard and Socony-Vacuum merged their interests in the region into a 50–50 joint venture. Standard-Vacuum Oil Co., or "Stanvac", operated in 50 countries, from East Africa to New Zealand, before it was dissolved in 1962.

The original Standard Oil Company corporate entity continues in existence and was the operating entity for Sohio; it is now a subsidiary of BP.[2] BP continued to sell gasoline under the Sohio brand until 1991.[53] Other Standard oil entities include "Standard Oil of Indiana" which became Amoco after other mergers and a name change in the 1980s, and "Standard Oil of California" which became the Chevron Corp.

Legacy and criticism of breakup

Some have speculated that if not for that court ruling, Standard Oil could have possibly been worth more than $1 trillion in the 2000s.[54] Whether the breakup of Standard Oil was beneficial is a matter of some controversy.[55] Some economists believe that Standard Oil was not a monopoly, and also argue that the intense free market competition resulted in cheaper oil prices and more diverse petroleum products. Critics claimed that success in meeting consumer needs was driving other companies out of the market who were not as successful. An example of this thinking was given in 1890, when Rep. William Mason, arguing in favor of the Sherman Antitrust Act, said: "trusts have made products cheaper, have reduced prices; but if the price of oil, for instance, were reduced to one cent a barrel, it would not right the wrong done to people of this country by the trusts which have destroyed legitimate competition and driven honest men from legitimate business enterprise".[56]

The Sherman Antitrust Act prohibits the restraint of trade. Defenders of Standard Oil insist that the company did not restrain trade; they were simply superior competitors. The federal courts ruled otherwise.

Some economic historians have observed that Standard Oil was in the process of losing its monopoly at the time of its breakup in 1911. Although Standard had 90 percent of American refining capacity in 1880, by 1911, that had shrunk to between 60 and 65 percent because of the expansion in capacity by competitors.[11]:79 Numerous regional competitors (such as Pure Oil in the East, Texaco and Gulf Oil in the Gulf Coast, Cities Service and Sun in the Midcontinent, Union in California, and Shell overseas) had organized themselves into competitive vertically integrated oil companies, the industry structure pioneered years earlier by Standard itself. In addition, demand for petroleum products was increasing more rapidly than the ability of Standard to expand. The result was that although in 1911 Standard still controlled most production in the older regions of the Appalachian Basin (78 percent share, down from 92 percent in 1880), Lima-Indiana (90 percent, down from 95 percent in 1906), and the Illinois Basin (83 percent, down from 100 percent in 1906), its share was much lower in the rapidly expanding new regions that would dominate U.S. oil production in the 20th century. In 1911, Standard controlled only 44 percent of production in the Midcontinent, 29 percent in California, and 10 percent on the Gulf Coast.[57]

Some analysts argue that the breakup was beneficial to consumers in the long run, and no one has ever proposed that Standard Oil be reassembled in pre-1911 form.[58] ExxonMobil, however, does represent a substantial part of the original company.

Since the breakup of Standard Oil, several companies, such as General Motors and Microsoft, have come under antitrust investigation for being inherently too large for market competition; however, most of them remained together.[59][60][61] The only company since the breakup of Standard Oil that was divided into parts like Standard Oil was AT&T, which after decades as a regulated natural monopoly, was forced to divest itself of the Bell System in 1984.[62]

Successor companies

Standard Oil's breakup split the company into 34 separate companies. The successor companies form the core of today's US oil industry. (Several of these companies were considered among the Seven Sisters who dominated the industry worldwide for much of the 20th century.) They include:

- Standard Oil of New Jersey (SONJ) – or Esso (S.O.), or Jersey Standard – merged with Humble Oil to form Exxon, now part of ExxonMobil. Standard Trust companies Carter Oil, Imperial Oil (Canada), and Standard of Louisiana were kept as part of Standard Oil of New Jersey after the breakup.

- Standard Oil of New York – or Socony, merged with Vacuum – renamed Mobil, now part of ExxonMobil.

- Standard Oil of California – or Socal – renamed Chevron, became ChevronTexaco, but returned to Chevron.

- Standard Oil of Indiana – or Stanolind, renamed Amoco (American Oil Co.) – now part of BP.

- Standard's Atlantic and the independent company Richfield merged to form Atlantic Richfield Company or ARCO, subsequently became part of BP, later sold to Tesoro Corporation, now part of Marathon Petroleum and in the process of being partially rebranded as Marathon or Speedway depending on each station ownership. Atlantic operations were spun off and bought by Sunoco.

- Continental Oil Company – or Conoco – later merged with Phillips Petroleum Company to form ConocoPhillips, downstream & midstream operations since spun off to form Phillips 66.

- Standard Oil of Kentucky – or Kyso – was acquired by Standard Oil of California, currently Chevron.

- The Standard Oil Company (Ohio) – or Sohio – the original Standard Oil corporate entity, acquired by BP in 1987.

- The Ohio Oil Co. – or The Ohio – marketed gasoline under the Marathon name. The company's upstream operations are now Marathon Oil while the downstream operations is now known as Marathon Petroleum, and was often a rival with the in-state Standard spinoff, Sohio.

| Standard Oil Co. Inc The "Seven Sisters", breakup 1911 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Ohio Oil Company renamed Marathon | The Standard Oil Company renamed Sohio | Standard Oil of New Jersey renamed Esso | Standard Oil of New York renamed Mobil | Standard Oil of California renamed Chevron | Standard Oil of Indiana renamed Amoco | Standard Oil of Kentucky | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Humble Oil Acq 1959 | Vacuum Oil Company Acq 1931 | Texaco Acq 2000 | Unocal Corporation Acq 2005 | American Oil Company Acq 1925 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exxon | Mobil | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marathon Petroleum | BP | ExxonMobil | Chevron | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other companies divested in the 1911 breakup:

- Anglo-American Oil Co. – acquired by Jersey Standard in 1930, now Esso UK.

- Buckeye Pipe Line Co.

- Borne-Scrymser Co. (chemicals)

- Chesebrough Manufacturing (acquired by Unilever)

- Colonial Oil

- Crescent Pipeline Co.

- Cumberland Pipe Line Co. (acquired by Ashland[63])

- Eureka Pipe Line Co.

- Galena-Signal Oil Co.

- Indiana Pipe Line Co.

- National Transit Co.

- New York Transit Co.

- Northern Pipe Line Co.

- Prairie Oil & Gas

- Solar Refining

- Southern Pipe Line Co.

- South Penn Oil Co. – eventually became Pennzoil, now part of Shell.

- Southwest Pennsylvania Pipe Line Co.

- Standard Oil of Kansas

- Standard Oil of Nebraska

- Swan and Finch

- Union Tank Lines

- Vacuum Oil Co.

- Washington Oil Co.

- Waters-Pierce

Note: Standard Oil of Colorado was not a successor company; the name was used to capitalize on the Standard Oil brand in the 1930s. Standard Oil of Connecticut is a fuel oil marketer not related to the Rockefeller companies.

Other Standard Oil spin-offs:

- Standard Oil of Iowa – pre-1911 – bought out by Chevron.

- Standard Oil of Minnesota – pre-1911 – bought out by Amoco.

- Standard Oil of Illinois - pre-1911 - bought out by Amoco.

- Standard Oil of Missouri – pre-1911 – dissolved.

- Standard Oil of Louisiana – originally owned by Standard Oil of New Jersey (now by Exxon).

- Standard Oil of Brazil – originally owned by Standard Oil of New Jersey (now by Exxon).

Rights to the name

Of the 34 "Baby Standards", 11 were given rights to the Standard Oil name, based on the state they were in. Conoco and Atlantic elected to use their respective names instead of the Standard name, and their rights would be claimed by other companies.

By the 1980s, most companies were using their individual brand names instead of the Standard name, with Amoco being the last one to have widespread use of the "Standard" name, as it gave Midwestern owners the option of using the Amoco name or Standard.

Three supermajor companies now own the rights to the Standard name in the United States: ExxonMobil, Chevron Corp., and BP. BP acquired its rights through acquiring Standard Oil of Ohio and merging with Amoco, and has a small handful of stations in the Midwestern United States using the Standard name. Likewise, BP continues to sell marine fuel under the Sohio brand at various marinas throughout Ohio. ExxonMobil keeps the Esso trademark alive at stations that sell diesel fuel by selling "Esso Diesel" displayed on the pumps. ExxonMobil has full international rights to the Standard name, and continues to use the Esso name overseas and in Canada. To protect its trademark Chevron has one station in each state it owns the rights to branded as Standard. Some of its Standard-branded stations have a mix of some signs that say Standard and some signs that say Chevron. Over time, Chevron has changed which station in a given state is the Standard station.

One of 15 Chevron stations branded as "Standard" to protect Chevron's trademark; this one is in Las Vegas, Nevada.

One of 15 Chevron stations branded as "Standard" to protect Chevron's trademark; this one is in Las Vegas, Nevada. A combination gasoline/diesel pump at an Exxon in Zelienople, Pennsylvania selling Exxon gasoline and "Esso Diesel".

A combination gasoline/diesel pump at an Exxon in Zelienople, Pennsylvania selling Exxon gasoline and "Esso Diesel". BP station with "torch and oval" Standard sign in Durand, Michigan.

BP station with "torch and oval" Standard sign in Durand, Michigan. BP continues to sell marine fuel under the Sohio brand at various marinas on Ohio waterways and in Ohio state parks in order to protect its rights in the Sohio and Standard Oil names. The Anderson Ferry Marina near Cincinnati, Ohio is pictured.

BP continues to sell marine fuel under the Sohio brand at various marinas on Ohio waterways and in Ohio state parks in order to protect its rights in the Sohio and Standard Oil names. The Anderson Ferry Marina near Cincinnati, Ohio is pictured.

See also

References

Notes

- "John D. and Standard Oil". Bowling Green State University. Archived from the original on 2008-05-04. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- "The Standard Oil Company; Ohio Charter No. 3675". Ohio Secretary of State. 1870-01-10.

- "Rockefellers Timeline". PBS. Archived from the original on 2008-04-26. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- "WARDEN WINTER HOME - Florida Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Jacob Vandergrift…Transportation Pioneer - Oil150.com". oil150.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Random Reminiscences of Men and Events by John D. Rockefeller". Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018 – via www.gutenberg.org.

- "Exxon Mobil - Our history". Exxon Mobil Corp. Archived from the original on 2008-11-12. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Dies, Edward (1969). Behind the Wall Street Curtain. Ayer. p. 76. ISBN 9780836911787.

- Grayson, Leslie E. (1987). Who and How in Planning for Large Companies: Generalizations from the Experiences of Oil Companies. p. 213. ISBN 9781349084128. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Udo Hielscher: Historische amerikanische Aktien, p. 68–74, ISBN 3921722063

- Daniel Yergin (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 910. ISBN 0-671-50248-4.

- Hidy, Ralph W. and Muriel E. Hidy. Pioneering in Big Business, 1882–1911: History of Standard Oil Co. (New Jersey) (1955).

- Jones, p 76

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- King, Gilbert. "The Woman Who Took on the Tycoon". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. pp. 145-150. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- David O. Whitten and Bessie Emrick Whitten, Handbook of American Business History: Manufacturing (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1990) p182

- "Standard Oil Company and Trust | American corporation". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2017-08-25. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- Josephson, Matthew (1962). The Robber Barons. Harcourt Trade. p. 277. ISBN 0156767902.

- Armentano, Dominick (1999), Antitrust and Monopoly: Anatomy of a Policy Failure, Oakland, CA: The Independent Institute, pp. 64–65

- Daniels, Eric (Winter 2009). "Antitrust with a Vengeance: The Obama Administration's Anti-Business Cudgel". The Objective Standard. Glen Allen Press. 14 (4): 84–85.

- Eliot Jones, The Trust Problem in the United States (1921) p 88 online

- Jeff Desjardins. "Chart: The Evolution of Standard Oil".

- Standard Oil controlled by a small group of families—see Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., London: Warner Books, 1998, (p.291)

- Jones, Eliot. The Trust Problem in the United States pp. 89–90 (1922) (hereinafter Jones).

- Arthur Schmidt, "Weetman Dickinson Pearson (Lord Cowdray)", in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2, 1068. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearborn 1997.

- Crow, Carl (2007). Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom (2nd ed.). Hong Kong:Earnshaw Books. ISBN 978-988-99633-3-0. pp. 41–42

- Cochran, S., Encountering Chinese Networks: Western, Japanese, and Chinese Corporations in China, 1880–1937, University of California Press, 2000, p. 38.

- Anderson, Irvine H. Jr., The Standard-Vacuum Oil Co. and United States East Asian Policy, 1933–1941, Princeton University Press, 1975, p. 16.

- Anderson p. 203.

- The Mei Foo Shield, A monthly publication of the North China Department of Standard Oil Co. of New York for its Far Eastern Staff.

- Cochran p.31

- Cochran p.32

- Anderson p. 106

- Mender, Peter (2010). Thirty Years a Mariner in the Far East 1907–1937, The Memoirs of Peter Mender, a Standard Oil Ship Captain on China's Yangtze River. Bangor, ME: Booklocker.

- The Mei Foo Shield, May 1926, November 1927

- Mobil Mariner, May 1958

- John A. DeNovo (1963). American Interests and Policies in the Middle East: 1900–1939. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 169–175. ISBN 9781452909363.

- Jones pp 58–59, 64.

- Jones. pg 58

- Jones. pp. 65–66.

- Rosenbaum, David Ira. Market dominance: how firms gain, hold, or lose it and the impact on economic performance. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998. p. 33

- Armentano, Dominick. Antitrust: The Case for Repeal. Ludwig von Mises Institute. 1999. p. 57.

- Manns, Leslie D., "Dominance in the Oil Industry: Standard Oil from 1865 to 1911" in David I. Rosenbaum ed., Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose it and the Impact on Economic Performance, p. 11 (Praeger 1998).

- Jones, p. 73.

- Jones, p 75–76.

- Jones, p. 80.

- See generally Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911).

- Rockefeller the richest man after the dissolution of 1911—see Yergin, op. cit., (p.113)

- "Standard ogre". The Economist. Archived from the original on 2017-09-30. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- "The Sherman Antitrust Act and Standard Oil" (PDF). University of Houston. January 9, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 9, 2014.

- "A Guide to the ExxonMobil Historical Collection". University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- "Standard Oil Company - Ohio History Central". www.ohiohistorycentral.org. Archived from the original on 2017-08-25. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- CFA, Jim Fink. "The Investing Secrets of the Richest Man the World Has Ever Known". fool.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2005-12-17. Retrieved 2005-12-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Congressional Record, 51st Congress, 1st session, House, June 20, 1890, p. 4100.

- Harold F. Williamsson and others, (1963) The American Petroleum Industry, 1899-1959, Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern Univ. Press, p.4-14.

- David I. Rosenbaum, Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose it and the Impact on Economic Performance, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1998, (pp.31–33)

- "Microsoft hit by record EU fine". CNN. March 25, 2004. Archived from the original on April 13, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- "Commission Decision of 24.03.2004 relating to a proceeding under Article 82 of the EC Treaty (Case COMP/C-3/37.792 Microsoft)" (PDF). Commission of the European Communities. April 21, 2004. Retrieved August 5, 2005.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-09-14. Retrieved 2013-11-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Pollack, Andrew (September 22, 1995). "AT&T Move Is a Reversal Of Course Set in 1980's". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016.

- "Ashland Oil & Refining Company - Lehman Brothers Collection". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

Bibliography

- Bringhurst, Bruce. Antitrust and the Oil Monopoly: The Standard Oil Cases, 1890–1911. New York: Greenwood Press, 1979.

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. London: Warner Books, 1998.

- Cochran, S., Encountering Chinese Networks: Western, Japanese, and Chinese Corporations in China, 1880-1937, University of California Press, 2000.

- Folsom, Jr., Burton W. John D. Rockefeller and the Oil Industry from The Myth of the Robber Barons. New York: Young America, 2003.

- Giddens, Paul H. Standard Oil Co. (Companies and men). New York: Ayer Co. Publishing, 1976.

- Henderson, Wayne. Standard Oil: The First 125 Years. New York: Motorbooks International, 1996.

- Hidy, Ralph W. and Muriel E. Hidy. History of Standard Oil Co. (New Jersey : Pioneering in Big Business 1882–1911). (Harper, 1956); 869pp; a standard scholarly study.

- Jones; Eliot. The Trust Problem in the United States 1922. Chapter 5; online free; another online edition

- Knowlton, Evelyn H. and George S. Gibb. History of Standard Oil Co.: Resurgent Years 1911–1927. New York: Harper & Row, 1956.

- Latham, Earl ed. John D. Rockefeller: Robber Baron or Industrial Statesman?, 1949. Primary and secondary sources.

- Manns, Leslie D. "Dominance in the Oil Industry: Standard Oil from 1865 to 1911" in David I. Rosenbaum ed, Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose it and the Impact on Economic Performance. Praeger, 1998. online edition

- Montague, Gilbert Holland. The Rise And Progress of the Standard Oil Co. (1902) online edition

- Montague, Gilbert Holland. "The Rise and Supremacy of the Standard Oil Co.," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 16, No. 2 (February, 1902), pp. 265–292 in JSTOR

- Montague, Gilbert Holland. "The Later History of the Standard Oil Co.," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 17, No. 2 (February, 1903), pp. 293–325 in JSTOR

- Nevins, Allan. John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise (1940); 710pp; favorable scholarly biography; online

- Nowell, Gregory P. (1994). Mercantile States and the World Oil Cartel, 1900–1939. Cornell University Press.

- Tarbell, Ida M. The History of the Standard Oil Co., 1904. The famous original exposé in McClure's Magazine of Standard Oil.

- Williamson, Harold F. and Arnold R. Daum. The American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Illumination, 1859–1899, 1959: vol 2, American Petroleum Industry: the Age of Energy 1899–1959, 1964. The standard history of the oil industry. online edition of vol 1

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Standard Oil. |

- The Dismantling of The Standard Oil Trust

- The History of the Standard Oil Co. by Ida Tarbell

- Educate Yourself- Standard Oil -- Part I

- Witch-hunting for Robber Barons: The Standard Oil Story by Lawrence W. Reed—argues Standard Oil was not a coercive monopoly.

- The Truth About the "Robber Barons"—arguing that Stand Oil was not a monopoly.

- Google Books: Dynastic America and Those Who Own It, 2003 (1921), by Henry H. Klein

- Standard Oil Trust original Stock Certificate signed by John. D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Henry M. Flagler and Jabez Abel Bostwick - 1882 CHARLES A. WHITESHOT: THE OIL-WELL DRILLER.A HISTORY OF THE WORLD'S GREATEST ENTERPRISE, THE OIL INDUSTRY Publisher: MANNINGTON 1905

- The Standard Oil (New Jersey) Collection – A digital collection of photographs from the documentary project directed by Roy E. Stryker.