Steppenwolf (novel)

Steppenwolf (originally Der Steppenwolf) is the tenth novel by German-Swiss author Hermann Hesse.

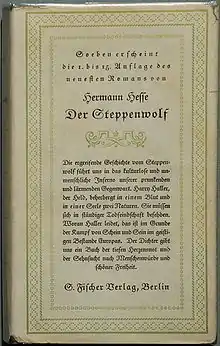

Cover of the original German edition | |

| Author | Hermann Hesse |

|---|---|

| Original title | Der Steppenwolf |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Autobiographical, novel, existential |

| Publisher | S. Fischer Verlag (Ger) |

Publication date | 1927 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 237 |

| ISBN | 0-312-27867-5 |

Originally published in Germany in 1927, it was first translated into English in 1929. The novel was named after the German name for the steppe wolf. The story in large part reflects a profound crisis in Hesse's spiritual world during the 1920s while memorably portraying the protagonist's split between his humanity and his wolf-like aggression and homelessness.[1]

Steppenwolf was wildly popular and has been a perpetual success across the decades, but Hesse later asserted that the book was largely misunderstood.[2]

Background and publication history

In 1924 Hermann Hesse married singer Ruth Wenger. After several weeks, however, he left Basel Germany, only returning near the end of the year. Upon his return he rented a separate apartment, adding to his isolation. After a short trip to Germany with Wenger, Hesse stopped seeing her almost completely. The resulting feeling of isolation and inability to make lasting contact with the outside world led to increasing despair and return of Hesse's suicidal thoughts.

Hesse began writing Steppenwolf in Basel, and finished it in Zürich. In 1926 he published a precursor to the book, a collection of poems titled The Crisis: From Hermann Hesse's Diary. The novel was later released in 1927. The first English edition was published in 1929 by Martin Secker in the United Kingdom and by Henry Holt and Company in the United States. That version was translated by Basil Creighton.

1926 was also the year when Hesse became acquainted with jazz music, attending Swiss performances of the Revue Nègre featuring Josephine Baker and Sidney Bechet; Steven C. Tracy, professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, writes that "the character of Pablo... was inspired by Bechet's playing"[3]

Plot summary

The book is presented as a manuscript written by its protagonist, a middle-aged man named Harry Haller, who leaves it to a chance acquaintance, the nephew of his landlady. The acquaintance adds a short preface of his own and then has the manuscript published. The title of this "real" book-in-the-book is Harry Haller's Records (For Madmen Only).

As the story begins, the hero is beset by reflections on his being ill-suited for the world of everyday, regular people, specifically for frivolous bourgeois society. In his aimless wanderings about the city he encounters a person carrying an advertisement for a magic theatre who gives him a small book, Treatise on the Steppenwolf. This treatise, cited in full in the novel's text as Harry reads it, addresses Harry by name and strikes him as describing himself uncannily. It is a discourse on a man who believes himself to be of two natures: one high, the spiritual nature of man; the other is low and animalistic, a "wolf of the steppes". This man is entangled in an irresolvable struggle, never content with either nature because he cannot see beyond this self-made concept. The pamphlet gives an explanation of the multifaceted and indefinable nature of every man's soul, but Harry is either unable or unwilling to recognize this. It also discusses his suicidal intentions, describing him as one of the "suicides": people who, deep down, knew they would take their own life one day. But to counter that, it hails his potential to be great, to be one of the "Immortals".

By chance, Harry encounters the man who gave him the book, just as the man has attended a funeral. He inquires about the magic theater, to which the man replies, "Not for everybody." When Harry presses further for information, the man recommends him to a local dance hall, much to Harry's disappointment.

When returning from the funeral, Harry meets a former academic friend with whom he had often discussed Oriental mythology, and who invites Harry to his home. While there, Harry is disgusted by the nationalistic mentality of his friend, who inadvertently criticizes a column Harry wrote. In turn, Harry offends the man and his wife by criticizing the wife's bust of Goethe, which Harry feels is too thickly sentimental and insulting to Goethe's true brilliance. This episode confirms to Harry that he is, and will always be, a stranger to his society.

Trying to postpone returning home, where he fears all that awaits him is his own suicide, Harry walks aimlessly around the town for most of the night, finally stopping to rest at the dance hall where the man had sent him earlier. He happens upon a young woman, Hermine, who quickly recognizes his desperation. They talk at length; Hermine alternately mocks Harry's self-pity and indulges him in his explanations regarding his view of life, to his astonished relief. Hermine promises a second meeting, and provides Harry with a reason to live (or at least a substantial excuse to continue living) that he eagerly embraces.

During the next few weeks, Hermine introduces Harry to the indulgences of what he calls the "bourgeois". She teaches Harry to dance, introduces him to casual drug use, finds him a lover (Maria) and, more importantly, forces him to accept these as legitimate and worthy aspects of a full life.

Hermine also introduces Harry to a mysterious saxophonist named Pablo, who appears to be the very opposite of what Harry considers a serious, thoughtful man. After attending a lavish masquerade ball, Pablo brings Harry to his metaphorical "magic theatre", where the concerns and notions that plagued his soul disintegrate as he interacts with the ethereal and phantasmal. The Magic Theatre is a place where he experiences the fantasies that exist in his mind. The Theater is described as a long horseshoe-shaped corridor with a mirror on one side and a great number of doors on the other. Harry enters five of these labeled doors, each of which symbolizes a fraction of his life.

Major characters

- Harry Haller – the protagonist, a middle-aged man

- Pablo – a saxophonist

- Hermine – a young woman Haller meets at a dance

- Maria – Hermine's friend

Critical analysis

In the preface to the novel's 1960 edition, Hesse wrote that Steppenwolf was "more often and more violently misunderstood" than any of his other books. Hesse felt that his readers focused only on the suffering and despair that are depicted in Harry Haller's life, thereby missing the possibility of transcendence and healing.[4]

Critical reception

From the very beginning, reception was harsh and it has had a long history of mixed critical reception and opinion. Already upset with Hesse's novel Siddhartha, political activists and patriots railed against him, and against the book, seeing an opportunity to discredit Hesse. Even close friends and longtime readers criticized the novel for its perceived lack of morality in its open depiction of sex and drug use, a criticism that indeed remained the primary rebuff of the novel for many years.[5] However, as society changed and formerly taboo topics such as sex and drugs became more openly discussed, critics came to attack the book for other reasons; mainly that it was too pessimistic, and that it was a journey in the footsteps of a psychotic and showed humanity through his warped and unstable viewpoint, a fact that Hesse did not dispute, although he did respond to critics by noting the novel ends on a theme of new hope.

American novelist Jack Kerouac dismissed it in Big Sur (1962), though popular interest was renewed in the 1960s – specifically in the psychedelic movement – primarily because it was seen as a counterculture book, and because of its depiction of free love and explicit drug use. It was also introduced in many new colleges for study, and interest in the book and in Hermann Hesse was feted in America for more than a decade afterwards.

English translations

- 1929: Basil Creighton

- 1963: Joseph Mileck revision of the Creighton translation

- 2010: Thomas Wayne

- 2012: David Horrocks

References in popular culture

Hesse's 1928 short story "Harry, the Steppenwolf" forms a companion piece to the novel. It is about a wolf named Harry who is kept in a zoo, and who entertains crowds by destroying images of German cultural icons such as Goethe and Mozart.

A paragraph in Hesse's 1943 novel The Glass Bead Game states that the term 'magic theater' is another name of the glass bead game itself.

The name Steppenwolf has become notable in popular culture for various organizations and establishments.

- In 1967, the band Steppenwolf, headed by German-born singer John Kay, took their name from the novel.

- The Belgian band DAAU (Die Anarchistische Abendunterhaltung) is named after one of the advertising slogans of the novel's magical theatre.

- The innovative Magic Theatre Company, founded in 1967 in Berkeley and which later became resident in San Francisco, takes its name from the "Magic Theatre" of the novel, and the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, founded in 1974 by actors Terry Kinney, Jeff Perry, and Gary Sinise, took its name from the novel.

- The lengthy track "Steppenwolf" appears on English rock band Hawkwind's album Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music and is directly inspired by the novel, including references to the magic theatre and the dual nature of the wolfman-manwolf (lutocost). Robert Calvert had initially written and performed the lyrics on "Distances Between Us" by Adrian Wagner in 1974. The song also appears on later, live Hawkwind CDs and DVDs.

- Danish acid rock band Steppeulvene (1967–68) also took their name from this novel.

- "He Was a Steppenwolf" is a song by Boney M. from the album Nightflight to Venus.

- Zbigniew Brzezinski includes a quote from Steppenwolf as an epigraph to his 1970 book Between Two Ages.[6]

- The United States of America's eponymous album features the track "The American Metaphysical Circus", which has lyrical references to the novel ("And the price is right/The cost of one admission is your mind").

- Be Here Now (1971), by author and spiritual teacher Richard Alpert (Ram Dass), contains an illustration of a door bearing a sign that reads "Magic Theatre – For Madmen Only – Price of Admission – Your Mind". This references an invitation that Steppenwolf's Harry Haller receives to attend an "Anarchist Evening at the Magic Theatre, For Madmen Only, Price of Admission Your Mind".

- The Black Ice, by Michael Connelly, has J. Michael Haller making a reference to the author when he mentioned that, if his illegitimate son took his surname, he would be "Harry Haller" instead of Harry Bosch.

- Paula Cole references the concept of the steppenwolf in her song "Pearl" on her 1999 album Amen.

- French singer Alizée sings her song "Gourmandises" to "le loup des steppes", literally "the wolf of the steppes" (2001).

- Steppenwolf was also referenced in the film Mall (2014). It is also read by the female lead, Maria, throughout the film Manny Lewis (2015).

- "Lobo da Estepe" by the Brazilian band Os Cascavelletes was also inspired by the book.

- The lyrics on the album Finisterre (2017) by the German black metal band Der Weg einer Freiheit are largely based on this book.

- "Жълти Стъкла" (Julti Stukla, or "Yellow Glass" from Bulgarian) released a song "Страстите Хесови" on YouTube on 6 August 2019. It largely and directly references Steppenwolf in its lyrics and description.

Film adaptation

The novel was adapted into the 1974 film Steppenwolf. It starred Max von Sydow and Dominique Sanda and was written and directed by Fred Haines.

See also

References

Citations

- Poplawski, p. 176

- Hesse, p. 7

- Tracy, Steven (2015). Hot Music, Ragmentation, and the Bluing of American Literature. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0817358969.

- Halkin, p. 126

- Mileck, p. 184

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew. "Between Two Ages". archive.org. The Viking Press. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Be Here Now [FATHER-SUN] – by Ram Dass". Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 2013-04-29.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "for madmen only - the blog". Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 2013-04-29.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

General sources

- Cornils, Ingo and Osman Durrani. 2005. Hermann Hesse Today. University of London Institute of Germanic Studies. ISBN 90-420-1606-X.

- Freedman, Ralph. 1978. Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis: A Biography. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-41981-2. OCLC 4076225.

- Halkin, Ariela. 1995. The Enemy Reviewed: German Popular Literature Through British Eyes Between the Two World Wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95101-4.

- Mileck, Joseph. 1981. Hermann Hesse: Life and Art. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04152-6.

- Poplawski, Paul. 2003. Encyclopedia of Literary Modernism. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-01657-8.

- Hesse, Herman. 1963. Steppenwolf. 19th edition. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ASIN: B0016RPX3K

- Ziolkowski, Theodore. 1969. "Foreword". The Glass Bead Game. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-1246-X.

- Malik, Hassan M. 2014. Steppenwolf: Genius of Suffering. Amazon Digital Services. ASIN: B00IMTX0O4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Steppenwolf. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Steppenwolf |

- Steppenwolf: The Genius of Suffering by Hassan M. Malik

- Steppenwolf at IMDb