Stratford-upon-Avon Canal

The Stratford-upon-Avon Canal is a canal in the south Midlands of England. The canal, which was built between 1793 and 1816, runs for 25.5 miles (41.0 km) in total, and consists of two sections. The dividing line is at Kingswood Junction, which gives access to the Grand Union Canal. Following acquisition by a railway company in 1856, it gradually declined, the southern section being un-navigable by 1945, and the northern section little better.

| Stratford-upon-Avon Canal | |

|---|---|

A stretch of the canal in Stratford | |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat length | 70 ft 0 in (21.34 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 7 ft 0 in (2.13 m) |

| Locks | 56 |

| Status | Navigable |

| Navigation authority | Canal and River Trust |

| History | |

| Original owner | Stratford-upon-Avon Canal Company |

| Principal engineer | William Clowes |

| Date of act | 1793 |

| Date of first use | 1800 |

| Date completed | 1816 |

| Date closed | 1939 |

| Date restored | 1964 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Kings Norton |

| End point | Stratford |

| Connects to | Worcester and Birmingham Canal, Grand Union Canal, River Avon |

The northern section was the setting for a high-profile campaign by the fledgling Inland Waterways Association in 1947, involving the right of navigation under Tunnel Lane bridge, which required the Great Western Railway to jack it up in order to allow boats to pass. These actions saved the section from closure. The southern section was restored by the National Trust between 1961 and 1964, after an attempt to close it was thwarted. The revived canal was re-opened by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, and responsibility for it was transferred to British Waterways in 1988.

Route

The Stratford-upon-Avon canal connects the Worcester and Birmingham Canal at Kings Norton to the River Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire. It consists of two sections, divided by a junction which connects it to the Grand Union Canal. The northern section from Kings Norton in the suburbs of Birmingham to Lapworth is level for the first 10.8 miles (17.4 km), following the 453-foot (138 m) Birmingham Level, but then descends quite rapidly through the Lapworth flight of 18 locks, to reach the junction. There is a choice of route to reach the Grand Union, as there are two locks side by side, one on the main line of the canal, and one on the branch, but a channel joins the bottom ends of both locks. The junction is almost exactly halfway along the canal.[1]

The southern section continues the descent with the final seven of the Lapworth locks, passing under the M40 motorway just before the final one. The locks are closely spaced until those at Preston Bagot are reached, after which there is a 6-mile (9.7 km) section with just one lock in the middle. This nearly-level section contains two of the canal's three iron aqueducts. The easy cruising is interrupted by the Wilmcote flight of eleven locks in just over a mile (1.6 km), soon after which the canal reaches Stratford-upon-Avon.[1]

Along the 25.5-mile (41.0 km) route of the canal, there are a total of 54 narrow locks.[1] Near King's Norton Junction there is a disused stop lock, which used to prevent the canal taking water from the Worcester and Birmingham Canal when they were separately owned, but is now left permanently open. It is unusual in that it has two guillotine gates which are made of wood. When operational, they moved vertically in iron frames, and were counterbalanced by weights.[2] A barge lock connects the terminal basin (Bancroft Basin[3]) with the River Avon.

Earlswood Lakes in Earlswood are feeder reservoirs to the canal. The three lakes were built between 1821 and 1822 and have a total capacity of 210 million gallons (950 megalitres (Ml)). The lakes consist of three separate pools; Terry's, Engine and Windmill Pool. They are retained by earth embankment. Until 1936 the water was pumped into the feeder by a beam engine, whose engine house can still be seen. The feeder was navigable for coal boats to reach the engine house and is now used for moorings.

Features

Stratford-upon-Avon Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From Kings Norton Junction at the northern end the canal immediately passes through the unusual King's Norton Stop Lock, the only guillotine-gated stop-lock on a canal.

After 3/4 mile is the only tunnel on the canal, at Brandwood. It is 352 yards (322 m) long, and like many canal tunnels it has no towpath; horses were walked over the hill and barges were pulled through the tunnel using a handrail on the wall of the tunnel, parts of which can still be seen.[2]

On the outskirts of Shirley the brick-built Major's Green Aqueduct carries the canal 10m above Aqueduct Road and the River Cole.

270 yards (250 m) further south is the electrically operated Shirley Draw Bridge which carries Drawbridge Road over the canal. It is normally closed and can be opened using a British Waterways key. The northern section also has a swing bridge (no.2, normally left open), a lift bridge (no.28), and another drawbridge (no. 26), all operated manually.

On the southern section interesting features of the canal include the unique barrel-roofed lock keeper's cottages to be found south of Kingswood Junction. All but two have been swamped by large modern extensions, but those at locks 28 and 31 are still in something like their original state, neither of them have either electricity supply or mains water.

Many of the accommodation bridges south of Kingswood Junction are split bridges of cast iron, with a central slot to accommodate the tow rope of horse-drawn boats.

The southern section of the canal passes over three cast iron aqueducts, unusual in that the towpaths are at the level of the canal bottom.[1]

Travelling south from Kingswood Junction, the first aqueduct is the modest Yarningale Aqueduct which carries the canal over a small stream near Preston Bagot, Warwickshire. This cast iron aqueduct was built in 1834 to replace the original wooden structure which was washed away when the stream flooded that year.

The second is the Wootton Wawen Aqueduct, just outside Wootton Wawen, where the canal crosses the A3400 main road.

The third is the Edstone Aqueduct (also known as Bearley) which at 475 feet (145 m),[4] is the longest in England.[5] The aqueduct crosses a minor road, the Birmingham and North Warwickshire railway and also the trackbed of the former Alcester Railway. There was once a pipe from the side of the canal that enabled locomotives to draw water to fill the locomotives' tanks.[6]

History

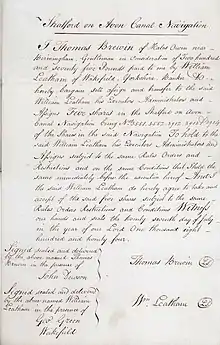

The Stratford-upon-Avon Canal was conceived as part of a network of canals which would allow coal from the Dudley Canal and the Stourbridge Canal to reach Oxford and London, without having to use the Birmingham canals, the management of which was seen as high-handed.[7] An Act was passed on 28 March 1793 for the construction of a canal from a junction with the Worcester and Birmingham Canal in Kings Norton to Stratford-upon-Avon. The Canal Company was empowered to raise £120,000 by issuing shares and an additional £60,000 if required.[8] The route would take it close to Warwick and Birmingham Canal at Lapworth, but the act did not include any provision for a direct connection with it, or with the River Avon at Stratford. Negotiations started with the Warwick and Birmingham, and to second act was obtained on 19 May 1795, to allow a connecting link to be built, despite rather unfavourable terms imposed on through traffic by the other company.[9]

Josiah Clowes was employed as the engineer, and construction began in November 1793, starting at the Kings Norton end. He was also working on the Dudley Canal's extension,[9] and another four canal schemes at the same time, and was the first great tunnel engineer. He died in December of the following year,[10] but work continued until the main line reached Hockley Heath in May 1796, one mile (1.6 km) short of the first lock at Lapworth. At this point, cutting ceased through lack of money, as the capital raised had all been spent.[9] The Dudley Canal extension through the Lappal tunnel was opened in early 1798, and with progress being made on the Warwick and Birmingham Canal, the Company obtained a third act of Parliament on 21 June 1799, which allowed it to raise more money, and included a diversion of the route further to the east near Lapworth, so that the length of the connecting link to the Warwick and Birmingham was only about 200 yards (180 m). Work restarted in 1799 under a new engineer called Samuel Porter, a former assistant of Clowes. He continued as far as Kingswood Junction, which was formally opened on 24 May 1802, after which cutting again ceased.[9]

Southern section

Construction only recommenced in 1812, under the leadership of William James of Stratford.[11] James, who had owned shares in the Company since 1793, had a wide interest in turnpike roads and railways, and following a tour of the north of England between 1802 and 1804, on which he investigated railways and canals, he expanded his business interests to include coal mining. He rose to become chairman of the Canal Company,[5] and personally bought the Upper Avon Navigation in 1813. He wanted to create a through route between the River Severn and the Midlands,[12] and so the Canal Company obtained a further act of Parliament on 12 May 1815, which authorised a connection between the canal and the Avon at Stratford, as well as enabling them to build reservoirs at Earlswood. The canal reached Stratford in June 1816 and a connection with the River Avon was made. The total cost of the canal had been around £297,000.[11]

The southern section of the canal never realised James' ambitions, as the Upper Avon was too tortuous and prone to floods to be a reliable through route. He spent some £6,000 on improvements to the Upper Avon locks in 1822, but over-reached himself, and was declared bankrupt shortly afterwards. For a while the upper river was managed by a syndicate of seven people, all connected with the canal, and the Canal Company took out a lease of it from 1842 for five years. Trade was mainly coal, which was conveyed from Stratford to Evesham.[12]

Traffic steadily built up, although tolls were low, to offset the costs imposed on goods passing through Kingswood Junction to the Warwick and Birmingham Canal. On the southern section, coal was taken to Stratford, from where it was sold, or passed along the Upper Avon or the Stratford and Moreton Tramway. Modest dividends were paid to shareholders from 1824, and the total traffic carried in 1838 was 181,708 tons, on which profits of £6,835 were made.[11] In 1845, the company agreed to sell the canal to the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway, who were also keen to purchase the Stratford and Moreton Tramway. It was not until January 1856 that the transaction was finally completed, and another year before the railway company took over day-to-day running.[13] Another change of ownership occurred in 1863, when the railway company was absorbed by the Great Western Railway.[14] Traffic gradually decreased, but the fall in receipts was faster than the fall in tonnage, as the railway took the long-distance loads.[15]

Decline and restoration

By the late 1930s the southern section had become derelict, although a water supply was maintained, which the GWR used to supply its engine shed in Stratford. The northern section was never officially closed, but traffic had virtually ceased by 1939. It was blocked when bridge no. 2, the Tunnel Lane lift bridge at Lifford, became faulty, and was replaced by the GWR with a fixed bridge which left insufficient height for a boat to pass.[16] After Lord Methuen raised the issue in the House of Lords in 1947, and was assured that the bridge "would be lifted at any time on notice of intended passage being given", Tom Rolt of the Inland Waterways Association (IWA) announced that he intended to pass under the bridge on 20 May 1947. Despite difficulties with the state of the canal, and the fact that the accompanying boat provided by the GWR got stuck, the bridge was reached. It had been jacked up and was resting on heavy timbers.[4] Robert Aickman, another of the founders of the IWA, had organised press coverage, and the story was reported in the national newspapers. IWA members were then encouraged to use the route.[16] Eric de Mare repeated the exercise in 1948, using a converted army pontoon. A horse-drawn ice breaker was used to create a channel through the weed on this occasion,[4] and the following year, Peter Scott asked for the bridge to be lifted. In 1950, the bridge, which had become known as Lifford Bridge, or Lifford Lane Bridge, was replaced with a working swing bridge.[16] The northern section of the canal was saved from dereliction by such pioneering efforts.[4] The bridge has now been removed altogether.

By the 1950s, the southern section was un-navigable by canal boats, as several of the locks could not be operated, and some of the small pounds between the locks of the Wilmcote flight were dry.[15] Problems with a bridge also began the process of restoring this section. Warwickshire County Council sought to obtain legal abandonment of the canal in 1958, as they wished to replace bridge 59 at Wilmcote without the expense of providing navigable headroom. A campaign against closure was mounted by the Inland Waterways Association and local activists. Two canoeists, who had used the canal recently, produced a dated toll ticket for their journey, which was offered as proof that the canal was not disused.[1] Retention of the canal was announced on 22 May 1959, and by 16 October, the British Transport Commission and the National Trust reported that they had agreed on the terms of a lease, under which the National Trust would be responsible for the restoration and maintenance of the southern section. The transfer of responsibility took place on 29 September 1960, and work began in March 1961. Although the Transport Commission made a contribution towards the cost,[15] the National Trust raised most of the £42,000 required to put it back into good order. The project was managed by David Hutchings,[4] who pioneered the use of voluntary labour, which would be used on many subsequent restorations, and assistance was also given by prisoners from Winson Green prison, the Army and the RAF Airfield Construction Branch. The canal was fully navigable by mid-1964, and Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother officially re-opened it on 11 July.[15] Its restoration was a turning point for the waterways movement in Britain.

The National Trust charged a private toll fee for navigation. Ten years after the re-opening, the Queen Mother performed the same ceremony for the Upper Avon Navigation, which had been derelict for more than a century, and the canal became part of a through route to the River Severn once more.[17] In 1986, the National Trust indicated that they would like to hand control of the canal back to the British Waterways Board, and held discussions on 7 October 1986. The canal was transferred on 1 April 1988, authorised by an order of the Secretary of State, which provided £1.5 million, phased over five years, to enable the canal to be brought up to standard.[18]

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jn with Worcester and Birmingham Canal | 52.4123°N 1.9223°W | SP053793 | |

| Brandwood Tunnel | 52.4132°N 1.9042°W | SP066794 | |

| Earlswood Lakes feeder | 52.3734°N 1.8326°W | SP114750 | |

| M42 Motorway bridge | 52.3626°N 1.8044°W | SP134738 | |

| Lapworth flight lock 2 | 52.3422°N 1.7595°W | SP164715 | |

| Kingswood Jn with Grand Union Canal | 52.3350°N 1.7271°W | SP186708 | |

| Lapworth flight lock 27 | 52.3230°N 1.7269°W | SP187694 | |

| Yarningale aqueduct | 52.2954°N 1.7318°W | SP183663 | |

| Wootton Wawen aqueduct | 52.2647°N 1.7693°W | SP158629 | |

| Edstone aqueduct | 52.2465°N 1.7642°W | SP161609 | |

| Wilmcote flight lock 40 | 52.2158°N 1.7519°W | SP170575 | |

| Wilmcote flight lock 50 | 52.2072°N 1.7387°W | SP179565 | |

| Jn with River Avon | 52.1915°N 1.7022°W | SP204548 |

See also

Bibliography

- "The Stratford-upon-Avon Canal". Canal Junction.

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2009). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (8th Ed.). Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-1-84623-010-3.

- Hadfield, Charles (1970). The Canals of the East Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4871-X.

- Hadfield, Charles (1985). The Canals of the West Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8644-1.

- Labrum, E. A. (1994). Civil Engineering Heritage. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-1970-X.

- Nicholson (2003). Nicholson Guides Vol 2: Severn, Avon & Birmingham. Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-721110-4.

- Pearson, Michael (2004). Canal Companion - Severn and Avon. J. M. Pearson & Son Ltd. ISBN 0-907864-79-1.

- Priestley, Joseph (1831). "Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and Railways of Great Britain".

- Skempton, Sir Alec; et al. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 1: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-2939-X.

- Squires, Roger (2008). Britain's restored canals. Landmark Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84306-331-5.

- Ware, Michael E (1989). Britain's Lost Waterways. Moorland Publishing Co Ltd.

References

- Cumberlidge 2009, pp. 282–284

- Nicholson 2006, p. 138

- Formerly the Bank Croft, a piece of common land by the river used as pasture: Lee, Sydney (1890). Stratford-on-Avon: From the Earliest Times to the Death of Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9781108048187.

- Ware 1989, pp. 28–29

- Skempton 2002, p. 357

- Warwickshire Railways website

- Hadfield 1985, p. 84

- Priestley 1831, pp. 598–600

- Hadfield 1970, p. 179

- Skempton 2002, p. 144

- Hadfield 1970, p. 180

- Hadfield 1985, pp. 146–147

- Hadfield 1970, p. 208

- "Oxford, Worcester & Wolverhampton Line". The Restoration & Archiving Trust. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Nicholson 2006, pp. 136–137

- "Historic Campaigns: Tunnel Lane Bridge, Lifford". Inland Waterways Association. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Squires 2008, p. 82

- Squires 2008, p. 122

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stratford-upon-Avon Canal. |