Stratford Dialectical and Radical Club

The Stratford Dialectical and Radical Club was a late nineteenth-century radical club based in Stratford, East London. Founded in 1880 by disaffected members of the National Secular Society who wished their organisation would involve itself in the social and political issues of the day rather than merely argue against the existence of God, it became one of the first openly socialist societies in London.[1] Although it only existed for a few years, the club attracted high-profile lecturers, including Russian Prince and dissident Peter Kropotkin, and is considered by scholars to illustrate a shift in popular perspective from religious dissent to socialist political theory.

Background and formation

The Stratford Dialectical and Radical Club was formed in 1880[2] when members of the National Secular Society decided to become more active in politics[3] and the burgeoning social reform movement[4] and less constrained by the NSS' focus on antitheism.[3] By 1878, NSS members of the Stratford Branch—"looking for a more political outlet for its energies"[5]—attempted to form themselves into a new Radical Party. They passed a resolution calling upon "men of advanced political opinions" to join them in the new endeavour.[5] They began booking socialist, rather than secularist, speakers for their public lectures from July 1878,[6] and the agitator Jesse Cocks also "ably and earnestly advocated" the branch take on socialist principles in 1878. However, it would take another two years for the branch to finally secede into the SDRC.[5]

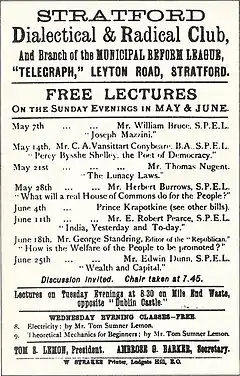

The break with the NSS was formally instigated in 1880 by Captain Tom Lemon,[3] the landlord of "The Telegraph" pub, in Leyton Road, Stratford, where the fledgeling group made its headquarters.[6] With Lemon was Ambrose Barker.[2] Barker later explained they were motivated specifically by the NSS' willingness to adopt a policy of what Barker termed "this worldism", or, the material conditions people were living under in contemporary society rather than the possibility or otherwise of an afterlife.[5] Martin Crick has suggested that this phenomenon was the result of "impatience with established methods of Secularist activity and anger at the movement's reluctance to commit itself to a definitive political creed",[6] and general dissatisfaction with the leadership of Charles Bradlaugh in the NSS, who personally opposed socialist ideas.[7]

The SDRC was one of many politically radical societies based in London in the late nineteenth century. Others included the Rose Street Club in Soho, supported by London's immigrant community; the Labour Emancipation League, formed a few years later by a faction within the SDRC;[8] the Manhood Suffrage Club; and the Marylebone Central Democratic Association.[9]

Organisation and activities

The SDRC's strategy for expansion was summed up by Joseph Lane as "take a room, pay a quarter's rent in advance then arrange a list of lecturers… paste-up bills in the streets all around…and [having] got a few members, get them to take it over and manage it as a branch".[10] They also wanted to introduce elements of amusement and education for their members:[3] both were seen as tools in the class struggle.[11]

The SDRC took political positions that were radical even compared with other radical clubs. For example, it supported the Pervomartovtsy assassins of Alexander II of Russia in 1881; and it was instrumental, with other radical London clubs, in the creation of the Social Democratic Federation, Britain's first socialist party, the same year. It was the only London club to support Irish Home Rule and oppose the Coercion Acts against the Irish following the 1882 Phoenix Park murders.[note 1] when support for Irish Home Rule was at a low ebb.[13] The Club also helped found the defence committee for Johann Most, whose Rose Street Club newspaper, Freiheit had also praised the assassination, resulting in his arrest.[14] The Club also organised mass-meetings on Mile End Waste,[note 2] following one in 1881 the Labour Emancipation League was founded.[6] Speakers at the SDRC included Peter Kropotkin in 1882, whom Barker had met at the Patriotic Club, and who "cordially" accepted the invitation to Stratford.[2] The club took part in popular national campaigns of the day, for example against the House of Lords in 1884. Alongside high-profile activities, local campaigns took place around East London issues, such as the threatened closure of Spitalfields Market.[14]

Legacy

Although it only existed for a short duration,[14] clubs such as the Stratford Dialectic and Radical have been identified as the origins of the anarchist movement in Britain,[20] due to its early espousal of an "anti-state, anti-capitalist" political program.[21] It was, Brian Simon, suggested, the first radical London Club with an outrightly socialist political philosophy,[22] and one of the major impetuses for the spread and popularisation of socialist ideas in London during the early 1880s.[11] According to Stan Shipley, the reasons for the Stratford NSS' split may seem trivial in hindsight, but at the time the relationship between secularism and socialism was a fundamental, and difficult, question. The formation and history of the Stratford Dialectic and Radical Club illustrates the gradual shift in popular politics from the former to the latter.[14]

Notes

- This was one of the issues over which the original members of the Club had split from the NSS over, as Bradlaugh, as a member of Parliament, had voted in favour of William Gladstone's Liberal government's Irish Coercion Bill in 1880.[12]

- Mile End Waste was the name given to the area of the Mile End Road immediately east of Whitechapel. Often used as a fair ground,[15] it was also used by groups and individuals to proselytize. The SD&RC organised meetings there, as did the East End Radicals.[16] A sprawling waste ground, a few years later it was described as being "a Gomorrah environed by a Babylon and the Gomorrah a spot where was vice, degradation and squalor, probably without parallel in any corner of the globe".[17] More recently it has been called "an East End equivalent of Hyde Park, hosting political debates and large-scale strike meetings". These included Rudolf Rocker in the early 20th century.[18] Around the period the SD&RC was operating, it saw mass-meetings by striking matchwomen in 1888,[19] in 1885 7,000 people demonstrated for the right to free speech,[16] and 20 years earlier William Booth had founded the Salvation Army there.[15]

References

- Worley 2009, pp. 80–81.

- Shipley 1971, p. 36.

- Bevir 2011, p. 113.

- Bevir 2011, p. 47.

- Shipley 1971, p. 40.

- Crick 1994, p. 21.

- Mansfield 1956, p. 279.

- Marshall 2009, p. 489.

- Bantman 2013, p. 28.

- Butterworth 2011, pp. 194–195.

- Crick 1994, p. 20.

- Walter 2007, p. 186.

- Fielding 1993, p. 96.

- Shipley 1971, p. 41.

- Railton 1912, p. 79.

- German & Rees 2012, p. 135.

- Anamosa 1904, p. 1.

- Portcities 2004.

- Gallhofer & Haslam 2003, p. 180.

- Bantman 2013, p. 27.

- Bloom 2010, p. 232.

- Simon 1974, p. 20.

Bibliography

- Anamosa (1904). The Anamosa Prison Press. Iowa: Anamosa. OCLC 20186997.

- Bantman, C. (2013). The French Anarchists in London, 1880–1914: Exile and Transnationalism in the First Globalisation. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-781386-58-3.

- Bevir, M. (2011). The Making of British Socialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69115-083-3.

- Bloom, C. (2010). Violent London: 2000 Years of Riots, Rebels and Revolts. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23028-947-5.

- Butterworth, A. (2011). The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Agents. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-44646-864-7.

- Crick, M. (1994). The History of the Social-Democratic Federation. Keele: Keele University Press. ISBN 978-1-85331-091-1.

- Fielding, S. (1993). Class and Ethnicity: Irish Catholics in England, 1880–1939. Buckingham: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-33509-993-1.

- Gallhofer, S.; Haslam, J. (2003). Accounting and Emancipation: Some Critical Interventions. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13460-050-2.

- German, L.; Rees, J. (2012). A People's History of London. London: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-84467-914-0.

- Mansfield, B. E. (1956). "The Socialism of William Morris". Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand. 7: 271–290. OCLC 1046242952.

- Marshall, P. (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. Oakland, CA: PM Press. ISBN 978-1-60486-270-6.

- Portcities (2004). "The site of the Mile End Waste". Portcities. Royal Museums Greenwich. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Railton, G. S. (1912). The Authoritative Life of General William Booth (1st ed.). New York: George H. Doran. OCLC 709512973.

- Shipley, S. (1971). Club Life and Socialism in Mid-Victorian London. History Workshop Pamphlets. V. Oxford: Journeyman, Ruskin College, Oxford. OCLC 943224963.

- Simon, B. (1974). Studies in the History of Education. London: Lawrence & Wishart. ISBN 978-0-85315-883-7.

- Walter, N. (2007). The Anarchist Past. Nottingham: Five Leaves. ISBN 978-1-90551-216-4.

- Worley, M. (2009). The Foundations of the British Labour Party: Identities, Cultures and Perspectives, 1900-39. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754667315.