Anarchism in China

Anarchism in China was a strong intellectual force in the reform and revolutionary movements in the early 20th century. In the years before and just after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty Chinese anarchists insisted that a true revolution could not be political, replacing one government with another, but had to overthrow traditional culture and create new social practices, especially in the family. "Anarchism" was translated into Chinese as 無政府主義 (wúzhèngfǔ zhǔyì) literally, "the doctrine of no government."

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

Chinese students in Japan and France eagerly sought out anarchist doctrines to first understand their home country and then to change it. These groups relied on education to create a culture in which strong government would not be needed because men and women were humane in their relations with each other in the family and in society. Groups in Paris and Tokyo published journals and translations that were eagerly read in China and the Paris group organized the Work-Study Programs to bring students to France. The late 19th and early 20th century Nihilist movement and anarchist communism in Russia were a major influence. The use of assassination as a tool was promoted by groups like the Chinese Assassination Corps, similar to the suicidal terror attacks by Russian anti-czarist groups. By the 1920s, however, the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party offered organizational strength and political change which drained support from anarchists.

Chinese student movements

The Chinese anarchist presence appeared first in France and Japan when the sons of wealthy families went abroad for study after the failed Boxer Rebellion. By 1906 national and provincial programs sent between five and six hundred students to Europe and about 10,000 to Japan. Japan, especially Tokyo, was the most popular destination because of its geographic proximity to China, its relatively affordable cost, and certain affinities between the two cultures. The Japanese language use of Chinese characters made it somewhat easier to learn. In Europe, Paris was particularly popular. Living in the city was relatively cheap, the French government subsidized the students, and France was seen as the center of Western civilization.[1]

The Chinese government officials may also have wanted to get radical students out of the country. The most radical students went to Europe and the more moderate students to Japan. That policy was to prove remarkably short-sighted as these foreign-educated students would use the methods and ideologies of European socialism and anarchism to completely transform Chinese society. In both locations of study, anarchism quickly became the most dominant of the western ideologies adopted by the students. In 1906, within a few months of each other, two separate anarchist student groups would form, one in Tokyo and one in Paris. The different locations, and perhaps also the different inclinations of the students being sent to each location, would result in two very different kinds of anarchism.[1]

Paris group

The so-called "Paris Group" gradually organized around the figures Zhang Renjie (also known as Zhang Jingzhang) and Li Shizeng, who arrived in Paris in 1902 as attaches to the Chinese embassy. They were soon joined by Wu Zhihui, an older and more intellectually rigorous figure and a radical critic of the Qing government. Wu introduced the group to his friend, Cai Yuanpei, who became a leader of the New Culture Movement,[2] and in the 《New Year's Dream》,which predicted the great changes in the world with the passage of time.[3] In 1906 Zhang, Li, and Wu founded the first Chinese anarchist organization, the World Society (世界社 Shijie she), sometimes translated as New World Society. In 1908, the World Society started a weekly journal, Xin Shiji 新世紀週報 (New Era or New Century; titled La Novaj Tempaj in Esperanto), to introduce Chinese students in France, Japan, and China to the history of European radicalism.[1] Other contributors included Wang Jingwei, Zhang Ji, and Chu Minyi, a student from Zhejiang who accompanied Zhang Renjie back from China and would be his assistant in the years to come.[4]

Li wrote that the influences of the Paris group could be divided into 3 main fields: radical libertarianism and anarchism; Darwinism and Social Darwinism; and the classical Chinese philosophers. While the Paris group was more reluctant than their counterparts in Tokyo to equate the teachings of Lao Tzu or the ancient well-field system with the anarchist communism they advocated, Li describes the group as consisting of young men who had received excellent educations in the Chinese classical tradition. He admits that the old thinking influenced them. The clear trend with the Paris group, however, was to dismiss and even actively oppose any association of anarchism with traditional culture. [1] For the Paris group, as the historian Peter Zarrow puts it, "science was truth and truth was science."[5]

Tokyo group

The Tokyo group drew on the same influences but in a different order of preference. While the Paris group was enamored of western science and western civilization, leaders such as Liu Shifu rooted their anarchism in political traditions native to Asia. In practical terms this meant the Paris group studied Esperanto, advocated anarcho-syndicalism, and drew heavily upon the works of Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. [1] The Tokyo group advocated an agrarian society built around democratically run villages organized into a free federation for mutual aid and defense. They based their ideology on a fusion of Taoism, Buddhism, and the "well field system" of ancient China, and gave preference to Leo Tolstoy over Kropotkin. Liu Shipei and He Zhen, his wife, split from the programs of the Zhang Binglin and other Tokyo leaders and returned to Shanghai. When it became public that the couple had been informers working for the Manchu official Duanfang, they were shunned.[6]

The Paris and Tokyo also initially advocated assassination, perhaps an indicator of the lasting influences of nihilism, but by 1910 conversion to anarchism was typically accompanied by the renunciation of assassination as a tactic.[1]

Cooperation and differences

In the early 20th century the anarchist movement was largely a western movement and the Chinese students studying in Paris were enthusiastically supportive of anarchism because they saw it as the most forward-thinking of all the western ideologies, and thus the furthest removed from what they perceived as a Chinese culture moribund by tradition. This position would repeatedly place them at odds with the Tokyo group who saw much that was good in traditional culture, and even argued that because China had not embraced the illusion of liberal capitalist democracy, it might be easier for them to make the transition to anarchism than it would be for the Europeans.

These differences, however, do not mean that the two groups did not cooperate. Because of the decentralised political structure and emphasis on local economic and political self-determination advocated by both groups, they were able to come to a tacit understanding that after the revolution both systems could peacefully coexist. The conflict was essentially one of values, priorities, and (by implication) methods for achieving the revolution which both advocated. In particular, the conflict over what place, if any, traditional Chinese philosophies should play in influencing anarchist thoughts and actions. This was a major source of friction and debate between the two groups.

The tendency for the advocates of different anarchisms to disagree on issues but agree to cooperate is not unique to the Chinese anarchist experience. For this reason many political scientists describe anarchism as a movement of movements. The ideological diversity inherent in such a movement of movements has historically been one of its great strengths but has also repeatedly undermined attempts to shape it into a cohesive force for social change.

Anarchism and nationalism

In the first phase of the movement, anarchists of both schools were generally participants in the Nationalist movement, even though in theory they repudiated nationalism and nation-states. They were influenced by foreign movements such as The People's Will and pan-Slavic nationalists like The Black Hand. Even though anarchism and nihilism are distinct and separate ideologies, at that time the popular press in Europe and China generally conflated the two. At the International Conference of Rome for the Social Defense Against Anarchists, anarchism was defined "as any act that used violent means to destroy the organization of society". This association with political violence promoted an early interest in anarchism among some Chinese radicals.

Nationalist attacks

The first attacks on the growing anarchist movement in China came from nationalists who saw anarchism as a threat to a strong, unified, centralized modern nation that could stand up to Western imperialism. As one reader wrote in a letter to Xin Shiji (The New World), the anarchist newspaper published by the Paris group:

If you people know only how to cry emptily that "We want no government, no soldiers, no national boundaries, and no State" and that you are for universal harmony, justice, freedom, and equality, I fear that those who know only brute force and not justice will gather their armies to divide up our land and our people.[1]

Nationalists also argued that only by building a popular front could the revolutionary movement defeat the Manchus and the Qing Dynasty, and that in the long run if anarchism was to succeed it must be preceded by a Republican system that would make China secure.

Anarchist response

The response of the Xin Shiji editors, written by Li Shizeng, was threefold. First, the revolution that the anarchists advocated would be global, simultaneous, decentralized, and spontaneous. Thus, foreign imperialists would be too occupied with the revolutions in their home countries to bother invading or harassing China. Secondly, they argued that having a strong centralized coercive government had not prevented China's enemies from attacking her in the past anyway. Finally, there was the moral point that in the long run, tyranny is tyranny, regardless of whether it is native or foreign. Therefore, the only logical approach for people who want freedom must be to oppose all authority be it Manchu, Han, foreign, or native.

Critics then and later asked how the Chinese anarchists could expect a global spontaneous revolution to come about. Li and the Paris group assumed, as did many radicals of all stripes all over the globe at that time, that Revolution was something akin to a force of nature. Within the context of their thinking, Revolution would come because it was obviously needed, and their role was simply to prepare people for it and help them see the obvious necessity of social change. This perspective provides important insight into the fundamentally evolutionary nature of the movement, and explains the movement's focus on education instead of organization building.

Results of collaboration

The involvement of prominent Nationalist figures indicates the role of personal relationships in the Paris groups' organizing. The individuals who founded that group had come out of the Nationalist movement and remained strongly tied to it by a network of close personal friendships. Therefore, it was natural for them to attempt to include their friends in their organizing in the hopes of winning those friends (and the influence they possessed) over to the anarchist cause.

The actual result of such collaboration was that the anarchists, not the Nationalists, compromised their positions since doing so allowed them to gain access to power positions in the Nationalist government that they theoretically opposed. That same year Jing Meijiu and Zhang Ji (another anarchist affiliated with the Tokyo group) would both be elected to the Republican parliament. Shifu and the Guangzhou group declared that by doing so they were traitors to the cause and proved their lack of commitment to the movement, but both men continued to call themselves anarchists and were active in promoting anarchism clear up to the late 1920s.

As a counterpoint to such collaboration, however, there is evidence that many more anarchists could have joined the new Nationalist government and gained positions of power and privilege but refused to do so because doing so would have violated their principles. As Scalapino and Yu put it "there can be little doubt that many refused to play the kind of political role that was so desperately needed in a period when trained personnel were extremely scarce compared to the tasks at hand."

Strategic issues

Arif Dirlik argues that these problems were indicative of lingering ambiguity in the definition of anarchism. More accurately, the issue was one of strategy. These men considered themselves anarchists because they were working for the long-term abolition of capitalism, the state, and coercive authority in general. In their vision, anarchism was a very long-term goal and not something they expected to see realized in their lifetimes. Chiang, for instance, expected that it would take 3,000 years to bring about the revolution they dreamed of.

Understanding that, it becomes easier to see why anarchists would be tempted to campaign for and hold political office or collaborate with sympathetic elements in the government, since doing so would help them achieve their long-term goals. This attitude is clearly distinct from the revolutionary anarchism of Kropotkin and Bakunin, or even of the Guangzhou group, which aimed for immediate revolution and the creation of an anarchist society in the immediate future.

This tendency to work for long-term revolution and focus on philosophy and theory instead of concrete organizing by some of the wealthier participants in the movement might have been rooted in class backgrounds. The split between wealthier philosophical anarchists, Marxists, or socialists, and working class revolutionaries can be a common feature of revolutionary movements.

Early growth of anarchism

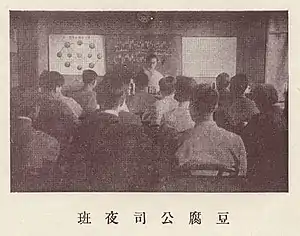

The Paris group declared that education was the most important activity revolutionaries could be involved in, and that only through educating the people could anarchism be achieved. [See for example Wu Zhihui: "Education as Revolution," The New Era, September 1908][7] Accordingly, they geared their activities towards education instead of assassination or grass roots organizing (the other two forms of activism which they condoned in theory). To these ends the Paris group set up a variety of businesses, including a soy products factory, which employed worker-students from China who wanted an education abroad. The students worked part-time and studied part-time, thus gaining a European education for a fraction of what it would cost otherwise. Many also gained first-hand experience on what it might mean to live, work, and study in an anarchist society. This study-abroad program played a critical role in infusing anarchist language and ideas into the broader nationalist and revolutionary movements as hundreds of students participated in the program. The approach demonstrated that anarchist organizational models based on mutual aid and cooperation were viable alternatives to profit-driven capitalist ventures.

The Paris and Tokyo groups both rallied to the nationalist cause. Li Shizeng, Wu Zhihui, and Zhang Renjie became early members of the Kuomintang and became close friends of Sun Yat-Sen. Sun received "considerable" economic assistance from Zhang. This collaboration was understandable given the emphasis by both the anarchists and the nationalists on the importance of Revolutionaries working together, and because of the eclecticism of Sun Yat-sen, who stated that "the end goal of the three peoples principles [was] communism and anarchism." Also, this view was shared by other Kuomintang ideologues.[8]

Anarchism as a mass movement

By 1911 anarchism had become the driving force behind popular mobilization and had moved beyond its initial association with relatively wealthy students studying abroad to become a genuine revolutionary movement among the people as a whole. There is some evidence that the grassroots workers movement which was developing at this time enjoyed a secondary influx of anarchist ideals as people who had been working in the United States were forced to return to China following the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This act severely limited (but did not eliminate) the flow of Chinese workers to and from the United States.

Influence of U.S. anarchists

The United States is influenced in many ways by world anarchism. Johann Most, the German anarchist who came to the United States in 1882, was described as "the Most vilified social radical"of his time, a man whose profuse advocacy of social unrest and fascination with dramatic destruction eventually led Emma Goldman to denounce him as a recognized authoritarian.[9]

In the United States, anarchists had been almost alone in the labor movement in explicitly opposing racism against Asian and Mexican workers, and when Emma Goldman came to speak in San Francisco in the 1890s there were several thousand Chinese workers in attendance. Additionally, from 1908 on, many thousands of Chinese workers in North America - particularly those working in California and the Pacific North-West - became members of the Industrial Union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The Wobblies (as IWW members were called) were the first American labor union to oppose the institution of White supremacy in an organized and deliberate fashion and to actively recruit Asians, Blacks, Latinos, and migratory workers. Their defense of Chinese immigrants who were being subjected to systematic harassment and discrimination won them a large base of membership among Chinese workers, and widespread support among the Chinese community in North America.

The influence of Chinese IWW members returning to China has gone largely unstudied, but the strong anarchist participation in the Chinese union movement and the willing reception that they met may owe something to this earlier relationship between Chinese workers and anarchist Revolutionaries.

The film《Lady L》is not only influence of America, but also the anarchist perception of women. The protagonist begins her career as a humble but pure washerwoman in a brothel; she is exposed to the film's disgusting sexual misconduct, but she is just an innocent bystander, so she is not abandoned by society. Anarchist views of prostitution have undergone a sea change; to the misogynist Proudhon, the prostitute became "the model of any female liberator". But Emma Goldman argues that traffic in women is not a moral aberration, but a symbol of capitalist wage slavery.[10]

Nationalist revolution of 1911

Following the Nationalist revolution of 1911 and the victory of the Revolutionary Alliance, which counted several prominent anarchists as movement elders, anarchists throughout China had a bit more room to engage in organizing. At the same time, Nationalist rule was by no means a guarantee of freedom to organize for antiauthoritarians, and government persecution was ongoing. With Nationalist goals of overthrowing the Manchu Qing dynasty having been achieved, the main ideological opposition to anarchism came from self-described Socialists, including the Chinese Socialist Society (CSS) and the Left wing of the nationalist movement which – following Sun Yet-Sen's lead – called itself socialist. Jiang Kanghu, who founded the Chinese Socialist Society in 1911, had been a contributor to the New Era (one of the publications of the Paris Group), and included the abolition of the state, the traditional family structure, and Confucian culture as planks of his parties platform.'

The main source of conflict came because the CSS wanted to retain market relations but supplement them with a broad social safety net, since they felt that without any incentive mechanism people would not produce anything and the society would collapse. Other sources of friction had to do with the CSS's focus on building the revolution in China first, and using elected office as a tool to do so – both significant deviations from classical anarchism. Jiang did not call himself an anarchist, so his party was generally perceived as being outside the movement, despite the similarities. In 1912 Jiang's party split into two factions, the pure socialists, led by the anarchist Buddhist monk Tai Xu, and the remains of the party led by Jiang.

Liu Shifu, who would go on to be one of the most significant figures in the anarchist movement in mainland China founded a group in Guangzhou later that same year, with an explicitly anarchist-communist platform.

Pure Socialist

The Pure Socialists revised platform included the complete abolition of property and an anarchist-communist economic system. Shifu criticized them for retaining the name "Socialist" but their platform was clearly anarchist so the two groups generally considered each other comrades. The emphasis on the importance of the Peasant struggle, which had been pioneered earlier by the Tokyo group, would also become a major subject of discussion and organizing among Chinese anarchists from both the Pure Socialists and the Guangzhou group in this period. It was anarchists who first pointed to the crucial role that the peasants must play in any serious revolutionary attempt in China, and anarchists were the first to engage in any serious attempts to organize the Peasants.

Guangzhou group

The main base of anarchist activity in mainland China during this phase was in Guangzhou, and the Paris and Tokyo groups continued to have significant influence. The Pure Socialists were also strongly involved, but because they were Buddhists as much as they were anarchists, were more concerned with promoting virtue and less focused on immediate revolution. By this time the Paris group had rendered their anarchism into a genuine philosophy that was more concerned with the place of the peaceful individual within society than with the day-to-day grind of government coercion against working people. Their tendency toward peace was somewhat surprising given the relatively wealthy backgrounds of most of the Paris group, but it would lead to increased friction between them and those comrades supportive of government coercion in Guangzhou.

The Guangzhou group is usually described as being "led" by Liu Shifu, and this is generally accurate insofar as we understand it as leadership by example since he was never granted any formal position or coercive authority by the group. Their most significant contributions at this stage were the foundation of "an alliance between intellectuals and workers" and their propaganda work which set out to differentiate anarchism from all the other socialisms that were gaining in popularity; and in so doing crystallized for the first time exactly what anarchism was.

Where the Paris group had preferred to outline their ideal in terms of negative freedoms, i.e., freedom from coercion, freedom from tradition, etc.; the Guangzhou group used positive assertions of rights and workers, women, peasants, and other oppressed groups to outline their vision of an anarchist society. Noticeably absent was any mention of ethnic minorities, since a basic part of their platform was the elimination of ethnic, racial, and national identities in favor of an internationalist identity that placed primary importance on loyalty to humanity as a whole, instead of to ones ethnic or racial group.

This position was formulated in response to the primacy placed on ethnicity by the Anti-Manchu movement, which sought to assert the illegitimacy of the Qing dynasty based in part on the fact that its members were part of an ethnic minority out of touch with the Han majority, a position which anarchists of all four major groups decried as racist and unbefitting a movement that claimed to be working for liberation. Their position, therefore, was that ethnicity-based organizing promoted Racism, and had no place in a Revolution that sought liberation for all of humanity.

In practical terms, the work of the movement at this stage was propaganda and organizing. Guangzhou anarchists founded a newspaper called Peoples Voice and began organizing workers, while in Taiyuan, in Shanxi province in the northwest, Jing Meijiu - who had converted to anarchism as part of the Tokyo group - founded an explicitly anarchafeminist worker-run factory/school to serve as a tool to help women simultaneously earn a living and receive an education.

Paris group influence

The similarity to the Paris group's "Diligent Work and Frugal Study" program is obvious. In 1912, members of the Paris group that had returned to China established the Promote Virtue Society whose leadership included prominent anarchists like Li Shizeng and Nationalists like Wang Jingwei.

The focus of that society, in keeping with the tendencies of the Paris group, was as much on virtuous and moral personal behavior as it was on Revolutionary praxis. Their rules for membership delineated different levels of commitment and discouraged members from eating meat and visiting prostitutes; and concretely forbade them from riding in Sedan chairs, taking concubines, or holding public office.

While it may be tempting to see such rules as superfluous, the evidence suggests we should take them seriously, since most of the anarchist organizations in China in this period included similar rules for their members. The goal was to create a cadre of Revolutionaries who would lead by example and help create a model for a new revolutionary culture. There are obvious parallels here to the traditional obligation for people involved in public life to set an example and promote virtue as well.

Diffusion of anarchist ideas

Since the 1890s, there have been many utopian stories spreading anarchist ideas, reflecting people's desire for a strong China, 《New Year's Dream》 is an excellent work of the utopian narrative tide initiated by CAI Yuanpei in Liang Qichao. 《New Year's Dream》 is not only a description of CAI Yuanpei's personal revolutionary trajectory, but also his unique contribution to anarchism. 《New Year's Dream》 is not only a description of CAI Yuanpei's personal revolutionary trajectory, but also his unique contribution to anarchism. On the one hand, CAI Yuanpei gave a concise and complete description of anarchism in time and space, which endowed anarchism with a real-world revolution. On the other hand, as far as political practice is concerned, the story contains more complexity than many European anarchists expected.[11]

The practical implications of such a broad diffusion of anarchist ideas, the setting in which it took place, and CAI Yuanpei's thought experiment that is a fascinating blend of anarchism, cosmopolitanism, and social evolution[12] are both strong indicators of the strong fusion of pragmatism and idealism that typified the Paris group's activities. In any case, the increased contact with actual flesh-and-blood workers had a profound effect on their propaganda and theory, with labor issues suddenly becoming a much more prominent part of their platform.

Not only labor issues, but also language is a constant topic of discussion in the dissemination of anarchist ideas. After the death of the young Liu Shifu, the Anarchist movement in China went through a difficult period. Until the eve of the May 4th movement, Esperanto was still a problem that anarchism needed to solve. After Chen Duxiu founded the 《New Youth》, a new culture movement publication, in 1918, the flagship journal published controversial discussions about Esperanto, an international language that even some non-anarchists were fascinated by. Anarchists used the opportunity to unite around this common topic and gain new visibility through widely published journals. Thus, during this period, Esperanto, as a more equal means of communication, addressed the "linguistic disadvantage" of East Asia without having to choose a language that was attached to a particular country. Esperanto embodies the true internationalist ideal. Also, it represents modern in a rational sense, and gets rid of the inconsistencies of the typical historically accepted language.

Anarchism as popular movement

Anarchism, as a mass movement, is another manifestation of modernity and the most thorough criticism of empires and nation-states. At the same time, it was part of the process of modernization and globalization that swept the world before 1914.[13]

By 1914 anarchism had become a genuine popular movement in China as increasing numbers of people from peasants and factory workers to intellectuals and students became disillusioned with the Nationalist government and its inability to realize the peace and prosperity it had promised.

A major liability that the movement had picked up along the way, however, was the extreme diffusion of anarchist idea to the point where it was becoming difficult to define exactly who was and who was not an anarchist. Liu Shifu set out to remedy that situation in a series of articles in Peoples Voice, which attacked Jiang Kanghu, Sun Yat-Sen, and the Pure Socialists.

The debates that ensued served for the first time to really crystallize what exactly was meant by anarchism in the broad sense. These articles were generally friendly in tone. The goal was to clearly differentiate between the different schools of thought that were available at that time. The letters directed at Sun Yet Sen and the Nationalists were aimed at exposing the ambiguities of their use of the word "socialism" to describe their goals, which were clearly not socialist according to any contemporary definition. The attacks on Jiang and the CSS sought to portray their vision of revolution and socialism as too narrow because it was focused on a single country, and to oppose their retention of market relations as part of their platform. The attack on the Pure Socialists was by far the mildest, with the main criticism being that if they were anarchists then they should call themselves anarchists and not socialists. Peoples Voice invited and printed responses from all parties, and their goal seems to have been the creation of an open and respectful debate among friends.

For the next five years the movement would grow slowly but steadily as each of the disparate groups continued their propaganda, education, and organizing projects. In 1915 the anarchist arguments for a Social Revolution that had originated a decade earlier with the original Paris group would find broader acceptance in the New Culture Movement which was pioneered by a small group of intellectuals in Beijing but spread to the rest of the county over the next four years, until it merged into the May Fourth movement.

The New Culture Movement was not anarchist, but in its glorification of science and extreme disdain for Confucianism and traditional culture it extended critiques that had originated with the Paris group, and the proliferation of anarchist thought during this period can be seen as a confirmation of the influence anarchists had on the movement from its foundation on; however, narchism at this time was externally positioned as a continuum between liberalism and national socialism.[14] The participants saw it as a conscious attempt to create a Chinese renaissance, and consciously sought to create and live the new culture that they espoused.

Decline in influence and the rise of Maoism

In 1919 the May 4th Movement swept the country, with anarchism a major influence and anarchists in prominent positions. It was at this time that the first Bolsheviks started organising in China and began contacting anarchist groups for aid and support. The anarchists, unaware that Bolsheviks had taken control in the Soviets and would suppress anarchism, helped them set up communist study groups – many of which were originally majority anarchist – and introduced the Bolsheviks into the Chinese labor and student movements.[15] [16]

By the beginning of 1920, anarchism was the most radical trend in Chinese socialism, and it served the Kuomintang by the end of 1920. For early anarchists had established personal and political relationships with Kuomintang leaders, independent of their ideology. But the radical ideology of anarchism, in its peculiar formulation of social interests and conflicts, makes itself almost as easily an instrument of counterrevolution as it is of revolution.[17]

In 1921, the newly formed Communist Party of China (CPC) began to take influence from the anarchist movement. First, the anarchists, almost on principle, did not have the institutions or organization to coordinate activities across regions. Second, activists began to realize that the Bolsheviks were Marxists, not anarchists – which caused a loss of prestige for the anarchists who had claimed the success of the Russian Revolution for their own. Third, and perhaps most critical, is that many anarchists expected their educational programs to work slowly, without short-term change; activists and workers who wanted immediate change turned to Bolshevism and the CPC. When the CPC entered into the First United Front with the Kuomintang against the warlords in 1924, they gained even broader access to the labor movement, and to mass movements in general. In a period of two years, the CPC grew from a membership of only a few hundred to over 50,000 through their support and assimilation of the various mass movements, leaving anarchists behind.

After the mid-1920s, anarchists, though politically irrelevant, remained active in the labor movement in southern China and continued to challenge communist organizations. At the end of the 1920s, the anarchists, betrayed by the Kuomintang in their struggle against Marxist ideology, exhausted their utility and slowly disappeared into a force in the Chinese revolutionary movement. After 1949, there were few visible signs of anarchist activity in neighboring countries or among overseas Chinese, and the post-revolutionary revival of interest in anarchism was short-lived.[18]

Hostilities between Chinese anarchism and Chinese communism

Where the first debates between Ou Shengbai and Chen Duxiu, his former teacher, had been friendly, later debates became actively hostile. Chen took the Marxist position that human nature was shaped by social and economic structures, and criticized Ou for his anarchist beliefs that human nature was good and people would be controlled by their sense of shame. The tension with communists was increased by anarchist criticisms of the Soviet Union. Reports from disillusioned anarchists had a big impact, such as Emma Goldman, who had many friends in China, and the wife of Kropotkin, who circulated first-hand reports of the failures of Bolshevism. [19]

A minority of anarchists, mostly from the Paris group, had been involved in the Kuomintang almost from its founding; but the majority of anarchists, in keeping with their stated principles against involvement in the exercise of coercive authority, had declined to participate in this alliance. The "Diligent Work-Frugal Study" program was one product of this collaboration of the anarchists with nationalists. When the Kuomintang purged the CPC from its ranks in 1927, the small minority of anarchists who had long participated in it urged their younger comrades to join the movement and utilize the Nationalist movement as a vehicle to defeat the Communists and realise anarchism. This drew immediate opposition from those anarchist groups that were still functioning. But even those critical of this opportunism, however, eventually joined in.

The result of this last collaboration was Li Shizeng's creation in 1927 of National Labor University (Laodong Daxue) in Shanghai, which was intended to be a domestic version of the Paris group's educational program and sought to create a new generation of Labor Intellectuals who would finally overcome the gap between "those who work with their hands" and "those who work with their minds." The university functioned for a few years before the Nationalist government decided the project was too subversive to allow it to continue and pulled funding.[20]

It had been acceptable for the anarchists to use government funding to promote anarchism as long as they did so in France, but when they began to do so at home, their "allies" were less than pleased. When the KMT initiated a second wave of repression against the few remaining mass movements, anarchists left the organization en masse and were forced underground as hostilities between the KMT and CPC – both of whom were hostile towards anti-authoritarians – escalated.

Anarchist loyalties or beliefs do not prevent the pursuit of national goals, even for those who formally reject nationalism.[21]

Status today

Overtly anarchist organizing has ceased to be a factor in modern Chinese politics due to the heavy repression levied against anti-authoritarians by the Maoist state since the time of the Cultural Revolution. However, as an underground resistance movement anarchism remains influential. Libertarian socialist and anarcho-communist currents have been particularly strong in the anti-dictatorship movement and in China's underground labor movement. The best known of these in the Western world is the Autonomous Beijing group, one of several groups responsible for organizing the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

Anarchism has cooperated with many revolutionary organizations, and struggle is a process of seeking common ground while reserving differences. In recent years, critics of the 1960s Cultural Revolution have argued that it was inspired by anarchist ideas. These ideas entered the Chinese Communist Party in the early 1920s and survived many years of revolution. There are some similarities between the themes of the Cultural Revolution and those of the Chinese revolution first proposed by the anarchists.[22]

References

- Scalapino (1961).

- Zarrow (1990), pp. 73–74.

- Li, Guangyi (2013). "A Chinese Anarcho-cosmopolitan Utopia: A Chinese Anarcho-cosmopolitan Utopia". Utopian Studies. 24 (1): 89–104. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.24.1.0089. ISSN 1045-991X.

- Bailey (2014), p. 24.

- Zarrow (1990), pp. 156–157.

- Zarrow (1990), p. 35.

- "Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas". blackrosebooks.net. Retrieved 2006-06-16.

- Dirlik, Arif (April 1986). "Vision and Revolution". Modern China. 12 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1177/009770048601200201. ISSN 0097-7004.

- "Anarchism and Cinema:", Film and the Anarchist Imagination, University of Illinois Press, pp. 9–59, 2020-10-26, ISBN 978-0-252-05221-7, retrieved 2020-12-17

- "Anarchism and Cinema:", Film and the Anarchist Imagination, University of Illinois Press, pp. 9–59, 2020-10-26, ISBN 978-0-252-05221-7, retrieved 2020-12-17

- Li, Guangyi (2013). "A Chinese Anarcho-cosmopolitan Utopia: A Chinese Anarcho-cosmopolitan Utopia". Utopian Studies. 24 (1): 89–104. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.24.1.0089. ISSN 1045-991X.

- Li, Guangyi (2013). "A Chinese Anarcho-cosmopolitan Utopia: A Chinese Anarcho-cosmopolitan Utopia". Utopian Studies. 24 (1): 89–104. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.24.1.0089. ISSN 1045-991X.

- Levy, Carl (2010). "Social Histories of Anarchism". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 4 (2): 1–44. doi:10.1353/jsr.2010.0003. ISSN 1930-1197.

- Levy, Carl (2010). "Social Histories of Anarchism". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 4 (2): 1–44. doi:10.1353/jsr.2010.0003. ISSN 1930-1197.

- Arif Dirlik, "Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870-1940 Studies in Global Social History

- Dirlik (1991), pp. 199-206.

- Dirlik, Arif (April 1986). "Vision and Revolution". Modern China. 12 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1177/009770048601200201. ISSN 0097-7004.

- DIRLIK, Arif (December 2012). "Anarchism in early twentieth century China: A contemporary perspective". Journal of Modern Chinese History. 6 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1080/17535654.2012.708183. ISSN 1753-5654.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 218-222.

- Dirlik (1991), pp. 262ff.

- DIRLIK, Arif (December 2012). "Anarchism in early twentieth century China: A contemporary perspective". Journal of Modern Chinese History. 6 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1080/17535654.2012.708183. ISSN 1753-5654.

- Dirlik, Arif (April 1986). "Vision and Revolution". Modern China. 12 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1177/009770048601200201. ISSN 0097-7004.

Sources

- Bailey, Paul (2014), "Cultural Productions in a New Global Space: Li Shizeng and the New Chinese Francophile Project in The Early Twentieth Century", in Lin, Pei-yin; Weipin Tsai (eds.), Print, Profit, and Perception: Ideas, Information and Knowledge in Chinese Societies, 1895-1949, Leiden: Brill, pp. 17–38, ISBN 9789004259102

- Bernal, M. "The Triumph of Anarchism over Marxism,"in M.C Wright, ed., China in Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971).

- Dirlik, Arif (1991). Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520072978.

- Dirlik, Arif (December 2012). "Anarchism in Early Twentieth Century China: A Contemporary Perspective". Journal of Modern Chinese History. 6 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1080/17535654.2012.708183. ISSN 1753-5654. S2CID 144753702 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Gasster, Michael. Chinese intellectuals and the revolution of 1911: the birth of modern Chinese radicalism (1969). Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 155–189.

- "Libertarian Socialism," Internet-Encyclopedia.org.

- Müller-Saini, Gotelind; Benton, Gregor (2006). "Esperanto and Chinese Anarchism in the 1920s and 1930s" (PDF). Language Problems and Language Planning. 30 (2): 173–192. doi:10.1075/lplp.30.2.06mul. ISSN 0272-2690.

- Rachline, Marianne (1965). "A Propos de l'anarchisme chinois". Le Mouvement social (50): 139–143. doi:10.2307/3777347. ISSN 0027-2671. JSTOR 3777347.

- Rapp, John A. (2012). Daoism and Anarchism. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781441178800.

- Scalapino, Robert A. and George T. Yu (1961). The Chinese Anarchist Movement (PDF). Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, Institute of International Studies, University of California..

- Shifu, "Goals and Methods of the Anarchist-Communist Party," The People's Voice, July 1914 (reprinted in Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas - Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE-1939), ed. Robert Graham).

- Zarrow, Peter Gue (1990). Anarchism and Chinese Political Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231071383.

- --. (1988). "He Zhen and Anarcho-Feminism in China,"," Journal of Asian Studies 47.4 (November): 796-813.

- Taoism as early Chinese anarchism by Murray Rothbard in his Histories of Economic Thought.

- Leanings toward anarchism in early Confucianism (PDF format) by philosopher Roderick Long.

External links

- Anarchists and the May 4 Movement in China by Nohara Shirõ (translated by Philip Billingsley).