Left-libertarianism

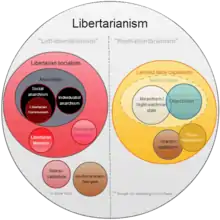

Left-libertarianism,[1][2][3][4][5] also known as egalitarian libertarianism,[6][7] left-wing libertarianism[8] or social libertarianism,[9] is a political philosophy and type of libertarianism that stresses both individual freedom and social equality. Left-libertarianism represents several related yet distinct approaches to political and social theory. In its classical usage, it refers to anti-authoritarian varieties of left-wing politics such as anarchism, especially social anarchism,[10] whose adherents simply call it libertarianism.[11] In the United States, it represents the left-wing of the libertarian movement[10] and the political positions associated with academic philosophers Hillel Steiner, Philippe Van Parijs and Peter Vallentyne that combine self-ownership with an egalitarian approach to natural resources.[10][12] This is done to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left–right or socialist–capitalist lines.[13]

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Individualism |

|---|

While maintaining full respect for personal property, socialist left-libertarians are opposed to capitalism and the private ownership of the means of production.[14][15][16][17] Other left-libertarians are skeptical of, or fully against, private ownership of natural resources, arguing in contrast to right-libertarians that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights and maintain that natural resources should be held in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.[18] Those left-libertarians who are more lenient towards private property support different property norms and theories such as usufruct,[19] or under the condition that recompense is offered to the local or even global community such as the Steiner–Vallentyne school.[20][21]

Market-oriented left-libertarianism, including Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's mutualism and Samuel Konkin III's agorism, appeals to left-wing concerns such as class, egalitarianism, environmentalism, gender, immigration and sexuality within the paradigm of free-market anti-capitalism.[10][22] Although libertarianism in the United States has become associated to classical liberalism and minarchism, with right-libertarianism being more known than left-libertarianism,[5] political usage of the term until then was associated exclusively with anti-capitalism, libertarian socialism and social anarchism and in most parts of the world such an association still predominates.[10][23]

Definition

People described as being left-libertarian or right-libertarian generally tend to call themselves simply libertarians and refer to their philosophy as libertarianism. In light of this, some political scientists and writers classify the forms of libertarianism into two or more groups[24][25] such as left-libertarianism[1] and right-libertarianism[2][4][5][26] to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital.[13] In the United States, proponents of free-market anti-capitalism consciously label themselves as left-libertarians and part of the libertarian left.[10][19]

Traditionally, libertarian was a term coined by the French libertarian communist[27] and Le Libertaire editor Joseph Déjacque[28][29][30][31][32] to mean a form of left-wing politics that has been frequently used to refer to anarchism[33][30][34][35] and libertarian socialism[36] since the mid- to late 19th century.[37][38] Sébastien Faure, another French libertarian communist, began publishing a new Le Libertaire in the mid-1890s while France's Third Republic enacted the so-called villainous laws (lois scélérates) which banned anarchist publications in France.[30][35] Libertarian was further popularized by the libertarian socialist Benjamin Tucker around the late 1870s and early 1880s.[39]

As a term, left-libertarianism has been used to refer to a variety of different political economic philosophies emphasizing individual liberty. With the modern development of right-libertarian co-opting[26][33][34][40] the term libertarian in the mid-20th century to instead advocate laissez-faire capitalism and strong private property rights such as in land, infrastructure and natural resources,[41] left-libertarianism has been used more often as to differentiate between the two forms,[10][12] especially in relation to property rights.[42]

While right-libertarianism refers to laissez-faire capitalism such as Murray Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism and Robert Nozick's minarchism,[2][4][26] socialist libertarianism "view[s] any concentration of power into the hands of a few (whether politically or economically) as antithetical to freedom and thus advocate for the simultaneous abolition of both government and capitalism."[5] According to Jennifer Carlson, right-libertarianism is the dominant form of libertarianism in the United States while left-libertarianism "has become a more predominant aspect of politics in western European democracies over the past three decades."[5] Socialist libertarianism has been included within a broad left-libertarianism in its original meaning.[10] Left-libertarianism also includes "the decentralist who wishes to limit and devolve State power, to the syndicalist who wants to abolish it altogether. It can even encompass the Fabians and the social democrats who wish to socialize the economy but who still see a limited role for the State."[43]

According to the textbook definition in The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy, left-libertarianism has at least three meanings, writing:

In its oldest sense, it is a synonym either for anarchism in general or social anarchism in particular. Later it became a term for the left or Konkinite wing of the free-market libertarian movement, and has since come to cover a range of pro-market but anti-capitalist positions, mostly individualist anarchist, including agorism and mutualism, often with an implication of sympathies (such as for radical feminism or the labor movement) not usually shared by anarcho-capitalists. In a third sense it has recently come to be applied to a position combining individual self-ownership with an egalitarian approach to natural resources; most proponents of this position are not anarchists.[10]

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy distinguishes left-libertarianism from right-libertarianism, arguing:

Libertarianism is often thought of as 'right-wing' doctrine. This, however, is mistaken for at least two reasons. First, on social—rather than economic—issues, libertarianism tends to be 'left-wing'. It opposes laws that restrict consensual and private sexual relationships between adults (e.g., gay sex, non-marital sex, and deviant sex), laws that restrict drug use, laws that impose religious views or practices on individuals, and compulsory military service. Second, in addition to the better-known version of libertarianism—right-libertarianism—there is also a version known as 'left-libertarianism'. Both endorse full self-ownership, but they differ with respect to the powers agents have to appropriate unappropriated natural resources (land, air, water, etc.).[44]

Terminology

As a term, left-libertarianism is used by some political analysts, academics and media sources, especially in the United States, to contrast it with the libertarian philosophy which is supportive of free-market capitalism and strong private property rights, in addition to supporting limited government and self-ownership which is common to both libertarian types.[45]

Peter Vallentyne describes left-libertarianism as the type of libertarianism holding that "unappropriated natural resources belong to everyone in some egalitarian manner."[46] Similarly, Charlotte and Lawrence Becker maintain that left-libertarianism most often refers to the political position that holds natural resources are originally common property.[47]

Followers of Samuel Edward Konkin III, who characterized agorism as a form of left-libertarianism[48][49] and strategic branch of left-wing market anarchism,[50] use the terminology as outlined by Roderick T. Long, who describes left-libertarianism as "an integration, or I'd argue, a reintegration of libertarianism with concerns that are traditionally thought of as being concerns of the left. That includes concerns for worker empowerment, worry about plutocracy, concerns about feminism and various kinds of social equality."[51]

Anthony Gregory maintains that libertarianism "can refer to any number of varying and at times mutually exclusive political orientations." Gregory describes left-libertarianism as maintaining interest in personal freedom, having sympathy for egalitarianism and opposing social hierarchy, preferring a liberal lifestyle, opposing big business and having a New Left opposition to imperialism and war.[52] Although some American libertarians such as Walter Block,[53] Harry Browne,[54] Leonard E. Read[55] and Murray Rothbard[56] may reject the political spectrum (especially the left–right political spectrum)[57][58] whilst denying any association with both the political right and left,[59] other American libertarians such as Kevin Carson,[19] Karl Hess,[60] Roderick T. Long[61] and Sheldon Richman[62] have written about libertarianism's left-wing opposition to authoritarian rule and argued that libertarianism is fundamentally a left-wing position.[22][63] Rothbard himself previously made the same point, rejecting the association of statism with the left.[64]

Philosophy

While all libertarians begin with a conception of personal autonomy from which they argue in favor of civil liberties and a reduction or elimination of the state, left-libertarianism encompasses those libertarian beliefs that claim the Earth's natural resources belong to everyone in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.[8][10][18][20][21]

Traditionally, left-libertarian schools are communist and market abolitionist, advocating the eventual replacement of money with labor vouchers or decentralized planning.[19][65] Contemporary left-libertarians such as Hillel Steiner, Peter Vallentyne, Philippe Van Parijs, Michael Otsuka and David Ellerman believe the appropriation of land must leave "enough and as good" for others or be taxed by society to compensate for the exclusionary effects of private property.[12][20] Socialist libertarians such as anarchists (green anarchists, individualist anarchists and social anarchists) and libertarian Marxists (council communists, De Leonists and Luxemburgists) promote usufruct and socialist economic theories, including collectivism, mutualism and syndicalism.[19][65] They criticize the state for being the defender of private property and believe capitalism entails wage slavery.[14][15][16][17]

Joseph Déjacque was the first to formulate libertarian ideas under the term libertarian. Later philosophers on the left would go onto adding detail to his political philosophy to study and document attitudes and themes relating to stateless socialism. In Déjacque's case, it was called libertarian communism.[27][31][30][35][36]

Personal autonomy

Left-libertarianism such as anarchism envisages freedom as a form of autonomy[66] which Paul Goodman describes as "the ability to initiate a task and do it one's own way, without orders from authorities who do not know the actual problem and the available means."[67] All anarchists oppose political and legal authority, but collectivist strains also oppose the economic authority of private property.[68] These social anarchists emphasize mutual aid whereas individualist anarchists extol individual sovereignty.[69]

Civil liberties

Left-libertarians have been advocates and activists of civil liberties, including free love and free thought.[70][71] Free love appeared alongside anarcha-feminism and advocacy of LGBT rights. Anarcha-feminism developed as a synthesis of radical feminism and anarchism and views patriarchy as a fundamental manifestation of compulsory government. It was inspired by the late-19th-century writings of early feminist anarchists such as Lucy Parsons, Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and Virginia Bolten. Advocates of free love viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of individual sovereignty and they particularly stressed women's rights as most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[72] Like other radical feminists, anarcha-feminists criticize and advocate the abolition of traditional conceptions of family, education and gender roles. Free Society (1895–1897 as The Firebrand, 1897–1904 as Free Society) was an anarchist newspaper in the United States that staunchly advocated free love and women's rights while criticizing comstockery, the censorship of sexual information.[73] Anarcha-feminism has voiced opinions and taken action around certain sex-related subjects such as pornography,[74] BDSM[75] and the sex industry.[75]

Free thought is a philosophical viewpoint that holds opinions should be formed on the basis of science, logic and reason in contrast with authority, tradition or other dogmas.[76][77] In the United States, free thought was an anti-Christian, anti-clerical movement whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide on religious matters. A number of contributors to Liberty were prominent figures in both free thought and anarchism. Catalan anarchist and free-thinker Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia established modern or progressive schools in Barcelona in defiance of an educational system controlled by the Catholic Church. The schools' stated goal was to "educate the working class in a rational, secular and non-coercive setting.[78] Fiercely anti-clerical, Ferrer believed in "freedom in education", i.e. education free from the authority of the church and state.[79]

Later in the 20th century, Austrian Freudo-Marxist Wilhelm Reich, who coined the term sexual revolution in one of his books from the 1940s,[80] became a consistent propagandist for sexual freedom, going as far as opening free sex-counseling clinics in Vienna for working-class patients (Sex-Pol stood for the German Society of Proletarian Sexual Politics). According to Elizabeth Danto, Reich offered a mixture of "psychoanalytic counseling, Marxist advice and contraceptives" and "argued for sexual expressiveness for all, including the young and the unmarried, with a permissiveness that unsettled both the political left and the psychoanalysts." The clinics were immediately overcrowded by people seeking help.[81] During the early 1970s, the English anarchist and pacifist Alex Comfort achieved international celebrity for writing the sex manuals The Joy of Sex[82] and More Joy of Sex.[83]

State

Many socialist left-libertarians are anarchists and believe the state inherently violates personal autonomy. Anarchists believe the state defends private property which they view as intrinsically harmful as this strongly prevents removal of illegitimate authority through inspection and vigilance. Robert Paul Wolff has argued that "since 'the state is authority, the right to rule', anarchism which rejects the State is the only political doctrine consistent with autonomy in which the individual alone is the judge of his moral constraints."[68]

Market-oriented left-libertarians argue that so-called free markets actually consist of economic privileges granted by the state. These left-libertarians advocate for free markets, termed freed markets, that are freed from these privileges. They see themselves as part of the free-market tradition of socialism.[84]

Although mainly related to libertarianism in the United States, Objectvism and right-libertarianism,[85][86][87] a minimal state or minarchism has also been advocated by left-libertarians, either as a path to anarchy or as an end in itself.[43][88] Some left-libertarians have proposed or supported a minimal welfare state on the grounds that social safety nets are short-term goals for the working class[89] and believe in stopping welfare programs only if it means abolishing both government and capitalism.[90] Other left-libertarians "prefer that corporate privileges be repealed before the regulatory restrictions on how those privileges may be exercised."[22]

Property rights

Socialist left-libertarians are opposed to private property and the private ownership of the means of production, supporting instead common or social ownership, or property rights based on occupation and use.[10][14][15][16][17][19] Other left-libertarians believe that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights[91][92] and maintain that natural resources ought to be held in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.[93]

Peter Mclaverty notes it has been argued that socialist values are incompatible with the concept of self-ownership, when this concept is considered "the core feature of libertarianism" and socialism is defined as holding "that we are social beings, that society should be organised, and individuals should act, so as to promote the common good, that we should strive to achieve social equality and promote democracy, community and solidarity."[94] However, it has also been argued that "property rights [...] do not pass judgment as to what rights individuals have to their own person [...] [and] to the external world" and that "the nineteenth-century egalitarian libertarians were not misguided in thinking that a thoroughly libertarian form of communism is possible at the level of principle."[95]

Economics

Left-libertarians like anarchists, libertarian Marxists and market-oriented left-libertarians argue in favor of libertarian socialist economic theories such as collectivism, communism, mutualism and syndicalism.[10][14][15][16][17][19] Daniel Guérin wrote that "anarchism is really a synonym for socialism. The anarchist is primarily a socialist whose aim is to abolish the exploitation of man by man. Anarchism is only one of the streams of socialist thought, that stream whose main components are concern for liberty and haste to abolish the State."[96]

Other left-libertarians make a libertarian reading of progressive and social-democratic economics to advocate a universal basic income. Building on Michael Otsuka's conception of "robust libertarian self-ownership", Karl Widerquist argues that a universal basic income must be large enough to maintain individual independence regardless of the market value of resources because people in contemporary society have been denied direct access to enough resource with which they could otherwise maintain their own existence in the absence of interference by people who control access to resources.[97] Updating Peter Kropotkin's empirical analysis and criticizing the right-libertarian theory of the state, Grant S. McCall and Wilderquist argue that contemporary societies fail to fulfill the Lockean proviso, equality and freedom are compatible, stateless egalitarian societies promote negative freedom better than capitalism, the appropriation principle supports small-scale community property and the private-property right system associated with right-libertarian capitalism was established not be appropriation but by a long history of state-sponsored violence.[98][99]

Schools of thought

Anarchism

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

Anarchism is a political philosophy that advocates stateless societies characterized by self-governed, non-hierarchical, voluntary institutions. It developed in the 19th century from the secular or religious thought of the Enlightenment, particularly Jean-Jacques Rousseau's arguments for the moral centrality of freedom.[100]

As part of the political turmoil of the 1790s and in the wake of the French Revolution, William Godwin developed the first expression of modern anarchist thought.[101][102] According to anarchist Peter Kropotkin, Godwin was "the first to formulate the political and economical conceptions of anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed in his work."[103] Godwin instead attached his ideas to an early Edmund Burke.[104] He is generally regarded as the founder of philosophical anarchism, arguing in Political Justice that government has an inherently malevolent influence on society and that it perpetuates dependency and ignorance.[102][105]

Godwin thought the proliferation of reason would eventually cause government to wither away as an unnecessary force. Although he did not accord the state with moral legitimacy, he was against the use of revolutionary tactics for removing the government from power, rather he advocated for its replacement through a process of peaceful evolution.[102][106] His aversion to the imposition of a rules-based society led him to denounce the foundations of law, property rights and even the institution of marriage as a manifestation of the people's "mental enslavement." He considered the basic foundations of society as constraining the natural development of individuals to use their powers of reasoning to arrive at a mutually beneficial method of social organization. In each case, government and its institutions are shown to constrain the development of our capacity to live wholly in accordance with the full and free exercise of private judgment.[102]

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

|

In France, revolutionaries began using anarchiste in a positive light as early as September 1793.[107] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was the first self-proclaimed anarchist (a label he adopted in his treatise What Is Property?) and is often described as the founder of modern anarchist theory.[108] He developed the theory of spontaneous order in society in which organisation emerges without a central coordinator imposing its own idea of order against the wills of individuals acting in their own interests, saying: "Liberty is the mother, not the daughter, of order." Proudhon answers his own question in What Is Property? with the famous statement that "property is theft." He opposed the institution of decreed property ("proprietorship") in which owners have complete rights to "use and abuse" their property as they wish[109] and contrasted this with usufruct ("possession") or limited ownership of resources only while in more or less continuous use. Proudhon wrote that "Property is Liberty" because it was a bulwark against state power.[110]

Proudhon's opposition to the state, organized religion and certain capitalist practices inspired subsequent anarchists and made him one of the leading social thinkers of his time. However, French anarchist Joseph Déjacque castigated Proudhon for his sexist economic and political views in a scathing letter written in 1857.[111][112][113] He argued that "it is not the product of his or her labour that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature."[114] Déjacque later named his anarchist publication Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social (Libertarian, Journal of the Social Movement) which was printed from 9 June 1858 to 4 February 1861. In the mid-1890s, French libertarian communist Sébastien Faure began publishing a new Le Libertaire while France's Third Republic enacted the so-called villainous laws (lois scélérates) which banned anarchist publications in France. Libertarianism has frequently been used as a synonym for anarchism since this time, especially in Europe.[30][115][116]

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist[117][118] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833 called The Peaceful Revolutionist was the first anarchist periodical published,[119] an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates.[119] Warren was a follower of Robert Owen and joined Owen's community at New Harmony, Indiana. Josiah Warren termed the phrase "Cost the limit of price", with "cost" referring not to monetary price paid, but the labor one exerted to produce an item.[120] Therefore, "[h]e proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce."[117] He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism (these included Utopia and Modern Times). Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' The Science of Society, published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories.[121] American individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker argued that the elimination of what he called "the four monopolies"—the land monopoly, the money and banking monopoly, the monopoly powers conferred by patents and the quasi-monopolistic effects of tariffs—would undermine the power of the wealthy and big business, making possible widespread property ownership and higher incomes for ordinary people, while minimizing the power of would-be bosses and achieving socialist goals without state action. Tucker influenced and interacted with anarchist contemporaries—including Lysander Spooner, Voltairine de Cleyre, Dyer Lum and William Batchelder Greene—who have in various ways influenced later left-libertarian thinking.[122]

The Catalan politician Francesc Pi i Margall became the principal translator of Proudhon's works into Spanish[123] and later briefly became president of Spain in 1873 while being the leader of the Democratic Republican Federal Party. For prominent anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker, "[t]he first movement of the Spanish workers was strongly influenced by the ideas of Pi y Margall, leader of the Spanish Federalists and disciple of Proudhon. Pi y Margall was one of the outstanding theorists of his time and had a powerful influence on the development of libertarian ideas in Spain. His political ideas had much in common with those of Richard Price, Joseph Priestly [sic], Thomas Paine, Jefferson, and other representatives of the Anglo-American liberalism of the first period. He wanted to limit the power of the state to a minimum and gradually replace it by a Socialist economic order."[124] Pi i Margall was a dedicated theorist in his own right, especially through book-length works such as La reacción y la revolución (Reaction and Revolution) in 1855, Las nacionalidades (Nationalities) in 1877 and La Federación (Federation) in 1880.

In the 1950s, the Old Right and classical liberals in the United States began identifying as libertarians in order to distance themselves from modern liberals and the New Left.[125] Since this time, it has become useful to distinguish this modern American libertarianism which promotes laissez-faire capitalism and generally a night-watchman state from anarchism.[2][3][4][126] Accordingly, the former is often described as right-libertarianism[2][3] or right-wing libertarianism[4] while synonyms for the latter include left-libertarianism[2][3][4][10] or left-wing libertarianism,[8] libertarian socialism[65] and socialist libertarianism.[5]

Classical liberalism and Georgism

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

|

Contemporary left-libertarian scholars such as David Ellerman, Michael Otsuka, Hillel Steiner, Peter Vallentyne and Philippe Van Parijs root an economic egalitarianism in the classical liberal concepts of self-ownership and appropriation. They hold that it is illegitimate for anyone to claim private ownership of natural resources to the detriment of others, a condition John Locke explicated in Two Treatises of Government.[127] Locke argued that natural resources could be appropriated as long as doing so satisfies the proviso that there remains "enough, and as good, left in common for others."[128] In this view, unappropriated natural resources are either unowned or owned in common and private appropriation is legitimate only if everyone can appropriate an equal amount or the property is taxed to compensate those who are excluded. This position is articulated in contrast to the position of right-libertarians who argue for a characteristically labor-based right to appropriate unequal parts of the external world such as land.[129] Most left-libertarians of this tradition support some form of economic rent redistribution on the grounds that each individual is entitled to an equal share of natural resources[130] and argue for the desirability of state social welfare programs.[131][132]

Economists since Adam Smith have opined that a land value tax would not cause economic inefficiency, despite their fear that other forms of taxation would do so.[133] It would be a progressive tax,[134] i.e. a tax paid primarily by the wealthy, that increases wages, reduces economic inequality, removes incentives to misuse real estate and reduces the vulnerability that economies face from credit and property bubbles.[135][136] Early proponents of this view include radicals such as Hugo Grotius,[12] Thomas Paine[12][137] and Herbert Spencer.[12] but the concept was widely popularized by the political economist and social reformer Henry George.[138] Believing that people ought to own the fruits of their labor and the value of the improvements they make, George was opposed to tariffs, income taxes, sales taxes, poll taxes, property taxes (on improvements) and to any tax on production, consumption or capital wealth. George was among the staunchest defenders of free markets and his book Protection or Free Trade was read into the United States Congressional Record.[139]

Early followers of George's philosophy called themselves single taxers because they believed the only economically and morally legitimate, broad-based tax is on land rent. As a term, Georgism was coined later, although some modern proponents prefer the less eponymous geoism,[140] leaving the meaning of geo- (from the Greek ge, meaning "earth") deliberately ambiguous. Earth Sharing,[141] geonomics[142] and geolibertarianism[143] are used by some Georgists to represent a difference of emphasis or divergent ideas about how the land value tax revenue should be spent or redistributed to residents, but all agree that economic rent must be recovered from private landholders. Within the libertarian left, George and his geoist movement influenced the development of democratic socialism,[144][145][146][147] especially in relation to British socialism[148] and Fabianism,[149] along with John Stuart Mill[150][151] and the German historical school of economics.[152] George himself converted George Bernard Shaw to socialism[153] and many of his followers are socialists who see George as one of their own.[154] Individuals described as being in this left-libertarian tradition include George, Locke, Paine, William Ogilvie of Pittensear, Spencer and more recently Baruch Brody, Ellerman, James O. Grunebaum, Otsuka, Steiner, Vallentyne and Van Parijs, among others.[12][155] Roberto Ardigò,[156] Hippolyte de Colins,[157] George,[157] François Huet,[157] William Ogilvie of Pittensear[155] Paine,[157] Spencer[156][158][159] and Léon Walras[157] are left-libertarians also seen as being within the left-liberal tradition of socialism.[155]

While socialists have been hostile to liberalism, accused of "providing an ideological cover for the depredation of capitalism", it has been pointed out that "the goals of liberalism are not so different from those of the socialists", although this similarly in goals has been described as being deceptive due to the different meanings liberalism and socialism give to liberty, equality and solidarity.[160][161] Liberal economists such as Léon Walras[162][163][164] considered themselves socialists and Georgism has also been considered by some as a form of socialism.[165] The idea that liberals or left-libertarians and state socialists disagree about means rather than ends has been similarly argued by Gustave de Molinari and Herbert Spencer.[61][166] According to Roderick T. Long, Molinari was the first theorist of free-market left-libertarianism.[167] Molinari has also influenced left-libertarian and socialists such as Benjamin Tucker and the Liberty circle.[168] Philosophical anarchist William Godwin, classical economists such as Adam Smith,[169][170] David Ricardo,[171] Thomas Robert Malthus, Nassau William Senior, Robert Torrens and the Mills, the early writings of Herbert Spencer,[172] socialists such as Thomas Hodgskin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, social reformer Henry George[172] and the Ricardian/Smithian socialists,[173][174] among others, "provided the basis for the further development of the left libertarian perspective."[175]

According to Noam Chomsky, classical liberalism is today represented by libertarian socialism, described as a "range of thinking that extends from left-wing Marxism through to anarchism." For Chomsky, "these are fundamentally correct" idealized positions "with regard to the role of the state in an advanced industrial society."[176] According to Iain McKay, "capitalism is marked by the exploitation of labour by capital" and "the root of this criticism is based, ironically enough, on the capitalist defence of private property as the product of labour. [...] Locke defended private property in terms of labour yet allowed that labour to be sold to others. This allowed the buyers of labour (capitalists and landlords) to appropriate the product of other people's labour (wage workers and tenants)."[177] In The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm, economist David Ellerman argues that "capitalist production, i.e. production based on the employment contract denies workers the right to the (positive and negative) fruit of their labour. Yet people's right to the fruits of their labour has always been the natural basis for private property appropriation. Thus capitalist production, far from being founded on private property, in fact denies the natural basis for private property appropriation."[178] Hence, left-libertarians such as Benjamin Tucker saw themselves as economic socialists and political individualists while arguing that their "anarchistic socialism" or "individual anarchism" was "consistent Manchesterism."[179] Peter Marshall argues that "[i]n general anarchism is closer to socialism than liberalism. [...] Anarchism finds itself largely in the socialist camp, but it also has outriders in liberalism. It cannot be reduced to socialism, and is best seen as a separate and distinctive doctrine."[180]

Geolibertarianism is a political movement and ideology that synthesizes libertarianism and geoist theory, traditionally known as Georgism.[181][182] Geolibertarians generally advocate distributing the land rent to the community via a land value tax as proposed by Henry George and others before him. For this reason, they are often called single taxers. Fred E. Foldvary coined geo-libertarianism in an article so titled in Land and Liberty.[183] In the case of geoanarchism, a proposed voluntaryist form of geolibertarianism as described by Foldvary, rent would be collected by private associations with the opportunity to secede from a geocommunity and not receive the geocommunity's services if desired.[184] The political philosopher G. A. Cohen extensively criticized the claim, characteristic of the Georgist school of political economy, that self-ownership and a privilege-free society can be realized simultaneously, also addressing the question of what egalitarian political principles imply for the personal behaviour of those who subscribe to them.[185] In Self-Ownership, Freedom, and Equality, Cohen argued that any system purporting to take equality and its enforcement seriously is not consistent with the full emphasis on self-ownership and negative freedom that defines market libertarian thought.[186] Tom G. Palmer has responded to Cohen's critique.[187][188]

Green politics

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

The green movement has been influenced by left-libertarian traditions, including anarchism, mutualism, Georgism and individualist anarchism. Peter Kropotkin provided a scientific explanation of how mutual aid is the real basis for social organization in his Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution.[189] New England transcendentalism (especially Henry David Thoreau and Amos Bronson Alcott) and German Romanticism, the pre-Raphaelites and other back to nature movements combined with anti-war, anti-industrialism, civil liberties and decentralization movements are all part of this tradition. In the modern period, Murray Bookchin and the Institute for Social Ecology elaborated these ideas more systematically.[190] Bookchin was one of the main influences behind the formation of the Alliance 90/The Greens, the first green party to win seats in state and national parliaments. Modern green parties attempt to apply these ideas to a more pragmatic system of democratic governance as opposed to contemporary individualist or socialist libertarianism. The green movement, especially its more left-wing factions, is often described by political scientists as left-libertarian.[191][192][193][194]

Political scientists see European political parties such as Ecolo and Groen in Belgium, Alliance 90/The Greens in Germany, or the Green Progressive Accord and GroenLinks in the Netherlands as coming out of the New Left and emphasizing spontaneous self-organisation, participatory democracy, decentralization and voluntarism, being contrasted to the bureaucratic or statist approach.[194] Similarly, political scientist Ariadne Vromen has described the Australian Greens as having a "clear left-libertarian ideological base."[195]

In the United States, green libertarianism is based upon a mixture of political third party values such as the environmentalism of the Green Party and the civil libertarianism of the Libertarian Party. Green libertarianism attempts to consolidate liberal and progressive values with libertarianism.[196]

Libertarian socialism

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

|

Libertarian socialism is a left-libertarian[197][198] tradition of anti-authoritarianism, anti-statism and libertarianism[199] within the socialist movement that rejects the state socialist notion of socialism as centralized state ownership and statist control of the economy[200] and the state.[201]

Libertarian socialism criticizes wage slavery relationships within the workplace,[202] instead emphasizing workers' self-management of the workplace[201] and decentralized structures of political organization,[203][204][205] asserting that a society based on freedom and justice can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.[206] Libertarian socialists advocate for decentralized structures based on direct democracy and federal or confederal associations[207] such as citizens' assemblies, libertarian municipalism, trade unions and workers' councils.[208][209]

Libertarian socialists make a general call for liberty[210] and free association[211] through the identification, criticism and practical dismantling of illegitimate authority in all aspects of human life.[212][213][214][215][216][217][218][219] Libertarian socialism opposes both authoritarian and vanguardist Bolshevism/Leninism and reformist Fabianism/social democracy.[220][221]

Past and present currents and movements commonly described as libertarian socialist include anarchism (especially anarchist schools of thought such as anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism[222] collectivist anarchism, green anarchism, individualist anarchism,[223][224][225][226] mutualism[227] and social anarchism) as well as Communalism, some forms of democratic socialism,[228][229] eco-socialism, guild socialism,[230] libertarian Marxist[231] (especially autonomism, council communism,[232] De Leonism, left communism, Luxemburgism[233][234] and workerism), various traditions of market socialism, several New Left schools of thought, participism, revolutionary syndicalism and some versions of utopian socialism.[235] Despite libertarian socialist opposition to Fabianism and modern social democracy, both have been considered as part of the libertarian left alongside other decentralist socialists.[43]

Left-libertarian Noam Chomsky considers libertarian socialism to be "the proper and natural extension" of classical liberalism "into the era of advanced industrial society."[176] Chomsky sees libertarian socialism and anarcho-syndicalist ideas as the descendants of the classical liberal ideas of the Age of Enlightenment,[236][237] arguing that his ideological position revolves around "nourishing the libertarian and creative character of the human being."[238] Chomsky envisions an anarcho-syndicalist future with direct worker control of the means of production and government by workers' councils which would select representatives to meet together at general assemblies.[239] The point of this self-governance is to make each citizen, in Thomas Jefferson's words, "a direct participator in the government of affairs."[240] Chomsky believes that there will be no need for political parties.[241] By controlling their productive life, Chomsky believes that individuals can gain job satisfaction and a sense of fulfillment and purpose.[242] Chomsky argues that unpleasant and unpopular jobs could be fully automated, carried out by workers who are specially remunerated, or shared among everyone.[243]

Anarcho-syndicalist Gaston Leval explained: "We therefore foresee a Society in which all activities will be coordinated, a structure that has, at the same time, sufficient flexibility to permit the greatest possible autonomy for social life, or for the life of each enterprise, and enough cohesiveness to prevent all disorder. [...] In a well-organised society, all of these things must be systematically accomplished by means of parallel federations, vertically united at the highest levels, constituting one vast organism in which all economic functions will be performed in solidarity with all others and that will permanently preserve the necessary cohesion."[244]

Market-oriented left-libertarianism

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

Carson–Long-style left-libertarianism is rooted in 19th-century mutualism and in the work of figures such as Thomas Hodgskin, French Liberal School thinkers such as Gustave de Molinari and American individualist anarchists like Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner, among others. Certain American left-wing market anarchists who come from the left-Rothbardian school such as Roderick T. Long and Sheldon Richman cite Murray Rothbard's homestead principle with approval to support worker cooperatives.[61][245] While American market-oriented left-libertarians after Benjamin Tucker tended to ally with the political right (with notable exceptions), relationships between such libertarians and the New Left thrived in the 1960s, laying the groundwork for modern free-market left-libertarianism.[61][64]

Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard was initially an enthusiastic partisan of the Old Right, particularly because of its general opposition to war and imperialism,[246] but long embraced a reading of American history that emphasized the role of elite privilege in shaping legal and political institutions, one that was naturally agreeable to many on the left. In the 1960s, he came increasingly to seek alliances on the left, especially with members of the New Left, in light of the Vietnam War,[247] the military draft and the emergence of the Black Power movement.[248] Working with other radicals such as Karl Hess and Ronald Radosh, Rothbard argued that the consensus view of American economic history, according to which a beneficent government has used its power to counter corporate predation, is fundamentally flawed. Rather, government intervention in the economy has largely benefited established players at the expense of marginalized groups, to the detriment of both liberty and equality. Moreover, the robber baron period, hailed by the right and despised by the left as a heyday of laissez-faire, was not characterized by laissez-faire at all, but it was a time of massive state privilege accorded to capital.[249] In tandem with his emphasis on the intimate connection between state and corporate power, he defended the seizure of corporations dependent on state largesse by workers and others[250] whilst arguing that libertarianism is a left-wing position.[61][64] By 1970, Rothbard had ultimately broke with the left, later allying with the burgeoning paleoconservative movement.[251][252] He criticized the tendency of left-libertarians to appeal to "'free spirits,' to people who don't want to push other people around, and who don't want to be pushed around themselves" in contrast to "the bulk of Americans", who "might well be tight-assed conformists, who want to stamp out drugs in their vicinity, kick out people with strange dress habits, etc." while emphasizing that this was relevant as a matter of strategy. He wrote that the failure to pitch the libertarian message to Middle America might result in the loss of "the tight-assed majority."[253] Those left-libertarians and left-wing followers of Rothbard who support private property do so under different property norms and theories, including Georgist,[254] homestead,[255] Lockean,[256][257] mutualist,[258] neo-Lockean[259] and utilitarian approaches.[260]

Some thinkers associated with market-oriented left-libertarianism, drawing on the work of Rothbard during his alliance with the left and on the thought of Karl Hess, came increasingly to identify with the left on a range of issues, including opposition to corporate oligopolies, state-corporate partnerships and war as well as an affinity for cultural liberalism. This left-libertarianism is associated with scholars such as Kevin Carson,[261][262] Gary Chartier,[263] Samuel Edward Konkin III,[264] Roderick T. Long,[265][266] Sheldon Richman,[22][267][268] Chris Matthew Sciabarra[269] and Brad Spangler,[270] who stress the value of radically free markets, termed freed markets to distinguish them from the common conception which these libertarians believe to be riddled with statist and capitalist privileges.[271] Also referred to as left-wing market anarchists,[272] these market-oriented left-libertarian proponents of this approach strongly affirm the classical liberal ideas of self-ownership and free markets, while maintaining that, taken to their logical conclusions, these ideas support strongly anti-corporatist, anti-hierarchical, pro-labor positions in economics; anti-imperialism in foreign policy; and thoroughly liberal or radical views regarding such cultural issues as gender, sexuality and race.[22] While adopting familiar libertarian views, including opposition to civil liberties violations, drug prohibition, gun control, imperialism, militarism and wars, left-libertarians are more likely to take more distinctively leftist stances on cultural and social issues as diverse as class, environmentalism, feminism, gender and sexuality.[273] Members of this school typically urge the abolition of the state, arguing that vast disparities in wealth and social influence result from the use of force—especially state power—to steal and engross land and acquire and maintain special privileges. They judge that in a stateless society the kinds of privileges secured by the state will be absent and injustices perpetrated or tolerated by the state can be rectified, concluding that with state interference eliminated it will be possible to achieve "socialist ends by market means."[274]

According to libertarian scholar Sheldon Richman, left-libertarians "favor worker solidarity vis-à-vis bosses, support poor people's squatting on government or abandoned property, and prefer that corporate privileges be repealed before the regulatory restrictions on how those privileges may be exercised." Left-libertarians see Walmart as a symbol of corporate favoritism, being "supported by highway subsidies and eminent domain", viewing "the fictive personhood of the limited-liability corporation with suspicion" and doubting that "Third World sweatshops would be the "best alternative" in the absence of government manipulation." Left-libertarians also tend to "eschew electoral politics, having little confidence in strategies that work through the government [and] prefer to develop alternative institutions and methods of working around the state."[22] Agorism is a market-oriented left-libertarian[10][22] tendency founded by Samuel Edward Konkin III which advocates counter-economics, working in untaxable black or grey markets and boycotting as much as possible the unfree, taxed market with the intended result that private voluntary institutions emerge and outcompete statist ones.[275][276][277][278]

Steiner–Vallentyne school

Contemporary left-libertarian scholars such as David Ellerman,[279][280] Michael Otsuka,[281] Hillel Steiner,[282] Peter Vallentyne[283] and Philippe Van Parijs[284] root an economic egalitarianism in the classical liberal concepts of self-ownership and land appropriation, combined with geoist or physiocratic views regarding the ownership of land and natural resources (e.g. those of Henry George and John Locke).[285][286] Neo-classical liberalism, also referred to as Arizona School liberalism or bleeding-heart libertarianism, focuses on the compatibility of support for civil liberties and free markets on the one hand and a concern for social justice and the well-being of the worst-off on the other.[287][288]

Scholars representing this school of left-libertarianism often understand their position in contrast to right-libertarians, who maintain that there are no fair share constraints on use or appropriation that individuals have the power to appropriate unowned things by claiming them (usually by mixing their labor with them) and deny any other conditions or considerations are relevant and that there is no justification for the state to redistribute resources to the needy or to overcome market failures. A number of left-libertarians of this school argue for the desirability of some state social welfare programs.[289][290] Left-libertarians of the Carson–Long left-libertarianism school typically endorse the labor-based property rights that Steiner–Vallentyne left-libertarians reject, but they hold that implementing such rights would have radical rather than conservative consequences.[291]

Left-libertarians of the Steiner–Vallentyne type hold that it is illegitimate for anyone to claim private ownership of natural resources to the detriment of others.[12][292] These left-libertarians support some form of income redistribution on the grounds of a claim by each individual to be entitled to an equal share of natural resources.[293][294] Unappropriated natural resources are either unowned or owned in common and private appropriation is only legitimate if everyone can appropriate an equal amount or if private appropriation is taxed to compensate those who are excluded from natural resources.[295]

Neo-libertarianism combines "the libertarian's moral commitment to negative liberty with a procedure that selects principles for restricting liberty on the basis of a unanimous agreement in which everyone's particular interests receive a fair hearing."[296] Neo-libertarianism has its roots at least as far back as 1980, when it was first described by James Sterba of the University of Notre Dame. Sterba observed that libertarianism advocates for a government that does no more than protection against force, fraud, theft, enforcement of contracts and other negative liberties as contrasted with positive liberties by Isaiah Berlin.[297] Sterba contrasted this with the older libertarian ideal of a night watchman state, or minarchism. Sterba held that it is "obviously impossible for everyone in society to be guaranteed complete liberty as defined by this ideal: after all, people's actual wants as well as their conceivable wants can come into serious conflict. [...] [I]t is also impossible for everyone in society to be completely free from the interference of other persons."[298] In 2013, Sterna wrote that "I shall show that moral commitment to an ideal of 'negative' liberty, which does not lead to a night-watchman state, but instead requires sufficient government to provide each person in society with the relatively high minimum of liberty that persons using Rawls' decision procedure would select. The political program actually justified by an ideal of negative liberty I shall call Neo-Libertarianism."[299]

See also

- Cellular democracy

- Civil libertarianism

- Cultural liberalism

- Cultural radicalism

- Drug liberalization

- Grassroots democracy

- Individualist feminism

- Left-libertarians (category)

- Libertarian Democrat

- Libertarian municipalism

- Libertarian paternalism

- Libertarian transhumanism

- Lockean proviso

- Market socialism

- Radical movement

References

- Bookchin, Murray; Biehl, Janet (1997). The Murray Bookchin Reader. New York: Cassell. p. 170.

- Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 4. ISBN 1846310253. ISBN 978-1846310256. "'Libertarian' and 'libertarianism' are frequently employed by anarchists as synonyms for 'anarchist' and 'anarchism', largely as an attempt to distance themselves from the negative connotations of 'anarchy' and its derivatives. The situation has been vastly complicated in recent decades with the rise of anarcho-capitalism, 'minimal statism' and an extreme right-wing laissez-faire philosophy advocated by such theorists as Murray Rothbard and Robert Nozick and their adoption of the words 'libertarian' and 'libertarianism'. It has therefore now become necessary to distinguish between their right libertarianism and the left libertarianism of the anarchist tradition."

- Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. p. 641. "The word 'libertarian' has long been associated with anarchism, and has been used repeatedly throughout this work. The term originally denoted a person who upheld the doctrine of the freedom of the will; in this sense, Godwin was not a 'libertarian', but a 'necessitarian'. It came however to be applied to anyone who approved of liberty in general. In anarchist circles, it was first used by Joseph Déjacque as the title of his anarchist journal Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social published in New York in 1858. At the end of the last century, the anarchist Sebastien Faure took up the word, to stress the difference between anarchists and authoritarian socialists."

- Newman, Saul (2010). The Politics of Postanarchism, Edinburgh University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0748634959. ISBN 978-0748634958. "It is important to distinguish between anarchism and certain strands of right-wing libertarianism which at times go by the same name (for example, Murray Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism). There is a complex debate within this tradition between those like Robert Nozick, who advocate a 'minimal state', and those like Rothbard who want to do away with the state altogether and allow all transactions to be governed by the market alone. From an anarchist perspective, however, both positions—the minimal state (minarchist) and the no-state ('anarchist') positions—neglect the problem of economic domination; in other words, they neglect the hierarchies, oppressions, and forms of exploitation that would inevitably arise in a laissez-faire 'free' market. [...] Anarchism, therefore, has no truck with this right-wing libertarianism, not only because it neglects economic inequality and domination, but also because in practice (and theory) it is highly inconsistent and contradictory. The individual freedom invoked by right-wing libertarians is only a narrow economic freedom within the constraints of a capitalist market, which, as anarchists show, is no freedom at all."

- Miller, Wilbur R. (2012). The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 1006.

- Sundstrom, William A. (16 May 2002). "An Egalitarian-Libertarian Manifesto". Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Sullivan, Mark A. (July 2003). "Why the Georgist Movement Has Not Succeeded: A Personal Response to the Question Raised by Warren J. Samuels". American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 62 (3): 612.

- Spitz, Jean-Fabien (March 2006). "Left-wing libertarianism: equality based on self-ownership". Cairn-int.info. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Grunberg, Gérard; Schweisguth, Etienne; Boy, Daniel; Mayer, Nonna, eds. (1993). The French Voter Decides. "Social Libertarianism and Economic Liberalism". University of Michigan Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-472-10438-3

- Long, Roderick T. (2012). "Anarchism". In Gaus, Gerald F.; D'Agostino, Fred, eds. The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. p. 227.

- Cohn, Jesse (20 April 2009). "Anarchism". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. p. 6. doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0039. ISBN 978-1-4051-9807-3.

'[L]ibertarianism' [...] a term that, until the mid-twentieth century, was synonymous with "anarchism" per se.

- Kymlicka, Will (2005). "libertarianism, left-". In Honderich, Ted. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 516. "'Left-libertarianism' is a new term for an old conception of justice, dating back to Grotius. It combines the libertarian assumption that each person possesses a natural right of self-ownership over his person with the egalitarian premiss that natural resources should be shared equally. Right-wing libertarians argue that the right of self-ownership entails the right to appropriate unequal parts of the external world, such as unequal amounts of land. According to left-libertarians, however, the world's natural resources were initially unowned, or belonged equally to all, and it is illegitimate for anyone to claim exclusive private ownership of these resources to the detriment of others. Such private appropriation is legitimate only if everyone can appropriate an equal amount, or if those who appropriate more are taxed to compensate those who are thereby excluded from what was once common property. Historic proponents of this view include Thomas Paine, Herbert Spencer, and Henry George. Recent exponents include Philippe Van Parijs and Hillel Steiner." ISBN 978-0199264797.

- Francis, Mark (December 1983). "Human Rights and Libertarians". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 29 (3): 462–472. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1983.tb00212.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1927). Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings. Courier Dover Publications. p. 150. ISBN 9780486119861.

It attacks not only capital, but also the main sources of the power of capitalism: law, authority, and the State.

- Otero, Carlos Peregrin (2003). "Introduction to Chomsky's Social Theory". In Otero, Carlos Peregrin (ed.). Radical Priorities. Chomsky, Noam Chomsky (3rd ed.). Oakland, California: AK Press. p. 26. ISBN 1-902593-69-3.

- Chomsky, Noam (2003). Carlos Peregrin Otero (ed.). Radical Priorities (3rd ed.). Oakland, California: AK Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 1-902593-69-3.

- Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilbur R. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 1006. "[S]ocialist libertarians view any concentration of power into the hands of a few (whether politically or economically) as antithetical to freedom and thus advocate for the simultaneous abolition of both government and capitalism".

- Carson, Kevin (15 June 2014). "What is Left-Libertarianism?". Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Vallentyne, Peter (March 2009). "Libertarianism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2009 ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

Libertarianism is committed to full self-ownership. A distinction can be made, however, between right-libertarianism and left-libertarianism, depending on the stance taken on how natural resources can be owned.

- Narveson, Jan; Trenchard, David (2008). "Left libertarianism". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Left Libertarianism. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; Cato Institute. pp. 288–289. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n174. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

Left libertarians regard each of us as full self-owners. However, they differ from what we generally understand by the term libertarian in denying the right to private property. We own ourselves, but we do not own nature, at least not as individuals. Left libertarians embrace the view that all natural resources, land, oil, gold, and so on should be held collectively. To the extent that individuals make use of these commonly owned goods, they must do so only with the permission of society, a permission granted only under the proviso that a certain payment for their use be made to society at large.

- Richman, Sheldon (3 February 2011). "Libertarian Left: Free-market anti-capitalism, the unknown ideal". The American Conservative. Archived 10 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Bookchin, Murray; Biehl, Janet (1997). The Murray Bookchin Reader. London: Cassell. p. 170. ISBN 0-304-33873-7.

- Long, Joseph. W (1996). "Toward a Libertarian Theory of Class". Social Philosophy and Policy. 15 (2): 310. "When I speak of 'libertarianism' [...] I mean all three of these very different movements. It might be protested that LibCap [libertarian capitalism], LibSoc [libertarian socialism] and LibPop [libertarian populism] are too different from one another to be treated as aspects of a single point of view. But they do share a common—or at least an overlapping—intellectual ancestry."

- Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilburn R., ed. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America. London: Sage Publications. p. 1006. ISBN 1412988764. "There exist three major camps in libertarian thought: right-libertarianism, socialist libertarianism, and left-libertarianism; the extent to which these represent distinct ideologies as opposed to variations on a theme is contested by scholars."

- Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. p. 565. "The problem with the term 'libertarian' is that it is now also used by the Right. [...] In its moderate form, right libertarianism embraces laissez-faire liberals like Robert Nozick who call for a minimal State, and in its extreme form, anarcho-capitalists like Murray Rothbard and David Friedman who entirely repudiate the role of the State and look to the market as a means of ensuring social order".

- Long, Roderick T. (2012). "The Rise of Social Anarchism". In Gaus, Gerald F.; D'Agostino, Fred, eds. The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. p. 223. "In the meantime, anarchist theories of a more communist or collectivist character had been developing as well. One important pioneer is French anarcho-communists Joseph Déjacque (1821–1864), who [...] appears to have been the first thinker to adopt the term "libertarian" for this position; hence "libertarianism" initially denoted a communist rather than a free-market ideology."

- Mouton, Jean Claude. "Le Libertaire, Journal du mouvement social". Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Woodcock, George (1962). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Meridian Books. p. 280. "He called himself a "social poet," and published two volumes of heavily didactic verse—Lazaréennes and Les Pyrénées Nivelées. In New York, from 1858 to 1861, he edited an anarchist paper entitled Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social, in whose pages he printed as a serial his vision of the anarchist Utopia, entitled L'Humanisphére."

- Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. London: Freedom Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-900384-89-9. OCLC 37529250.

- Robert Graham, ed. (2005). Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300 CE–1939). Montreal: Black Rose Books. §17.

- Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. p. 641. "The word 'libertarian' has long been associated with anarchism, and has been used repeatedly throughout this work. The term originally denoted a person who upheld the doctrine of the freedom of the will; in this sense, Godwin was not a 'libertarian', but a 'necessitarian'. It came however to be applied to anyone who approved of liberty in general. In anarchist circles, it was first used by Joseph Déjacque as the title of his anarchist journal Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social published in New York in 1858. At the end of the last century, the anarchist Sebastien Faure took up the word, to stress the difference between anarchists and authoritarian socialists".

- Bookchin, Murray (January 1986). "The Greening of Politics: Toward a New Kind of Political Practice". Green Perspectives: Newsletter of the Green Program Project (1). "We have permitted cynical political reactionaries and the spokesmen of large corporations to pre-empt these basic libertarian American ideals. We have permitted them not only to become the specious voice of these ideals such that individualism has been used to justify egotism; the pursuit of happiness to justify greed, and even our emphasis on local and regional autonomy has been used to justify parochialism, insularism, and exclusivity – often against ethnic minorities and so-called deviant individuals. We have even permitted these reactionaries to stake out a claim to the word libertarian, a word, in fact, that was literally devised in the 1890s in France by Elisée Reclus as a substitute for the word anarchist, which the government had rendered an illegal expression for identifying one's views. The propertarians, in effect – acolytes of Ayn Rand, the earth mother of greed, egotism, and the virtues of property – have appropriated expressions and traditions that should have been expressed by radicals but were willfully neglected because of the lure of European and Asian traditions of socialism, socialisms that are now entering into decline in the very countries in which they originated".

- Fernandez, Frank (2001). Cuban Anarchism. The History of a Movement. Sharp Press. p. 9. "Thus, in the United States, the once exceedingly useful term "libertarian" has been hijacked by egotists who are in fact enemies of liberty in the full sense of the word."

- Ward, Colin (2004). Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 62. "For a century, anarchists have used the word 'libertarian' as a synonym for 'anarchist', both as a noun and an adjective. The celebrated anarchist journal Le Libertaire was founded in 1896. However, much more recently the word has been appropriated by various American free-market philosophers."

- "The Week Online Interviews Chomsky". Z Magazine. 23 February 2002. Retrieved 12 July 2019. "The term libertarian as used in the US means something quite different from what it meant historically and still means in the rest of the world. Historically, the libertarian movement has been the anti-statist wing of the socialist movement. In the US, which is a society much more dominated by business, the term has a different meaning. It means eliminating or reducing state controls, mainly controls over private tyrannies. Libertarians in the US don't say let's get rid of corporations. It is a sort of ultra-rightism."

- "150 years of Libertarian".

- "160 years of Libertarian".

- Comegna, Anthony; Gomez, Camillo (3 October 2018). "Libertarianism, Then and Now". Libertarianism. Cato Institute. "[...] Benjamin Tucker was the first American to really start using the term "libertarian" as a self-identifier somewhere in the late 1870s or early 1880s." Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Rothbard, Murray (2009) [1970s]. The Betrayal of the American Right (PDF). Mises Institute. ISBN 978-1610165013.

One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, 'our side,' had captured a crucial word from the enemy. 'Libertarians' had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over.

- Hussain, Syed B. (2004). Encyclopedia of Capitalism. Vol. II : H-R. New York: Facts on File Inc. p. 492. ISBN 0816052247.

In the modern world, political ideologies are largely defined by their attitude towards capitalism. Marxists want to overthrow it, liberals to curtail it extensively, conservatives to curtail it moderately. Those who maintain that capitalism is a excellent economic system, unfairly maligned, with little or no need for corrective government policy, are generally known as libertarians.

- Widerquist, Karl. "Libertarianism: left, right, and socialist". Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Marshall, Peter (2009) [1991]. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (POLS ed.). Oakland, California: PM Press. p. 641. "Left libertarianism can therefore range from the decentralist who wishes to limit and devolve State power, to the syndicalist who wants to abolish it altogether. It can even encompass the Fabians and the social democrats who wish to socialize the economy but who still see a limited role for the State." ISBN 978-1604860641.

- Vallentyne, Peter (20 July 2010). "Libertarianism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Frankel Paul, Ellen; Miller Jr., Fred; Paul, Jeffrey (12 February 2007). Liberalism: Old and New. 24. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-70305-5.

- Vallentyne, Peter (20 July 2010). "Libertarianism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Becker, Charlotte B.; Becker, Lawrence C. (2001). Encyclopedia of Ethics. 3. Taylor & Francis US. p. 1562. ISBN 978-0-4159-3675-0.

- "Smashing the State for Fun and Profit Since 1969: An Interview With the Libertarian Icon Samuel Edward Konkin III (a.k.a. SEK3)". Spaz.org. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- D'Amato, David S. (27 November 2018). "Black-Market Activism: Samuel Edward Konkin III and Agorism". Libertarianism.org. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Konkin III, Samuel Edward. "An Agorist Primer" (PDF). Kopubco.com. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Long, Roderick. T. (4 January 2008). "An Interview With Roderick Long". Liberalis in English. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Gregory, Anthony (21 December 2006). "Left, Right, Moderate and Radical". LewRockwell.com. Archived 25 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. 25 December 2014.

- Block, Walter (2010). "Libertarianism Is Unique and Belongs Neither to the Right Nor the Left: A Critique of the Views of Long, Holcombe, and Baden on the Left, Hoppe, Feser, and Paul on the Right". Journal of Libertarian Studies. 22. pp. 127–170.

- Browne, Harry (21 December 1998). "The Libertarian Stand on Abortion". HarryBrowne.Org. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Read, Leonard E. (January 1956). "Neither Left Nor Right". The Freeman. 48 (2): 71–73.

- Rothbard, Murray (1 March 1971). "The Left and Right Within Libertarianism". WIN: Peace and Freedom Through Nonviolent Action. 7 (4): 6–10. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Rothbard, Murray (1 March 1971). "The Left and Right Within Libertarianism". WIN: Peace and Freedom Through Nonviolent Action. 7 (4): 6–10. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Raimondo, Justin (2000). An Enemy of the State. Chapter 4: "Beyond left and right". Prometheus Books. p. 159.

- Machan, Tibor R. (2004). "Neither Left Nor Right: Selected Columns". 522. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 0817939822. ISBN 9780817939823.

- Hess, Karl (18 February 2015). "Anarchism Without Hyphens & The Left/Right Spectrum". Center for a Stateless Society. Tulsa Alliance of the Libertarian Left. Retrieved 17 March 2020. "The far left, as far as you can get away from the right, would logically represent the opposite tendency and, in fact, has done just that throughout history. The left has been the side of politics and economics that opposes the concentration of power and wealth and, instead, advocates and works toward the distribution of power into the maximum number of hands."

- Long, Roderick T. (8 April 2006). "Rothbard's 'Left and Right': Forty Years Later". Mises Institute. Rothbard Memorial Lecture, Austrian Scholars Conference 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Richman, Sheldon (1 June 2007). "Libertarianism: Left or Right?". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2020. "In fact, libertarianism is planted squarely on the Left, as I will try to demonstrate here."

- Comegna, Anthony; Gomez, Camillo (3 October 2018). "Libertarianism, Then and Now". Libertarianism. Cato Institute. "I think you're right that the right-wing associations with libertarianism—that is mainly a product of the 20th century and really the second half of the 20th century, and before that it was overtly left-wing, and radically left-wing, for the most part, in almost all iterations." Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Rothbard, Murray (Spring 1965). "Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty". Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought. 1 (1): 4–22.

- Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

- Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. p. 42.

- Goodman, Paul (1972). Little Prayers and Finite Experience.

- Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. pp. 42–43.

- Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. pp. 8–10.

- "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy". Ncc-1776.org. 1 December 1996. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Nicolas Walter. "Anarchism and Religion"". Theanarchistlibrary.org. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy". Ncc-1776.org. 1 December 1996. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- Emma Goldman: Making Speech Free, 1902–1909. p. 551. "Free Society was the principal English-language forum for anarchist ideas in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century."

- "An Anarchist Defense of Pornography by Boston Anarchist Drinking Brigade". Theanarchistlibrary.org. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "Interview with an Anarchist Dominatrix". Archived from the original on 18 December 2002. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Freethinker – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- "Free thought". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Fidler, Geoffrey C. (Spring–Summer 1985). "The Escuela Moderna Movement of Francisco Ferrer: "Por la Verdad y la Justicia". History of Education Quarterly. History of Education Society. 25 (1/2): 103–132. doi:10.2307/368893. JSTOR 368893.

- "Francisco Ferrer's Modern School". Flag.blackened.net. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- Reich, Wilhelm; Wolfe, Theodore P, trans. (1945). The Sexual Revolution: Toward a Self-governing Character Structure (in German: Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf). Berlin: Sexpol-Verlag (German ed.). New York City: Orgone Institute Press (English ed.).

- Danto, Elizabeth Ann (2007) [2005]. Freud's Free Clinics: Psychoanalysis & Social Justice, 1918–1938. Columbia University Press. pp. 118–120, 137, 198, 208.

- Comfort, Alex (1972). The Joy of Sex. Crown.

- Comfort, Alex (1973). More Joy of Sex: A Lovemaking Companion to The Joy of Sex. Crown.

- Chartier, Gary. Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Minor Compositions. p. 1. ISBN 978-1570272424.

- Gregory, Anthony (10 May 2004). "The Minarchist's Dilemma". Strike the Root: A Journal of Liberty. Archived 12 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Peikoff, Leonard (7 March 2011). "What role should certain specific governments play in Objectivist government?". Peikoff.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Peikoff, Leonard (3 October 2011). "Interview with Yaron Brook on economic issues in today's world (Part 1)". Peikoff.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Hain, Peter (July/August 2000). "Rediscovering our libertarian roots". Chartist. Archived 21 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Chomsky Replies to Multiple Questions About Anarchism". Z Magazine. ZCommunications. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

Anarchists propose other measures to deal with these problems, without recourse to state authority. [...] Social democrats and anarchists always agreed, fairly generally, on so-called 'welfare state measures'.

- McKay, Iain, ed. (2012). "J.5 What alternative social organisations do anarchists create?". An Anarchist FAQ. II. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-849351-22-5. OCLC 182529204.

- Carlson (2012). p. 1007. "[Left-libertarians] disagree with right-libertarians with respect to property rights, arguing instead that individuals have no inherent right to natural resources. Namely, these resources must be treated as collective property that is made available on an egalitarian basis."

- Narveson, Jan; Trenchard, David (2008). "Left Libertarianism". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 288–289. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n174. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.